NICOLA DEANE

CONCLUSION Irresolution

CAUTION: STEPS

Walter Benjamin, One-Way Street and Other Writings (1979: 61)

Work on good prose has three steps: a musical stage when it is composed, an architectonic one when it is built, and a textile one when it is woven.

[a text is] no longer a finished corpus of writing, some content enclosed in a book or its margins, but a differential network, a fabric of traces referring endlessly to something other than itself, to other differential traces.

Jaques Derrida, “Living On/borderlines” (1979: 84)

Scriptorium within DOMUS: Reflections on the irresolved territory of the virtual archive

In translating my research project (theory and practice) to a digital platform I had to rethink my original designs of presentation to find the appropriate means for digitally engaging the reader. The points at which I recognised problems of translation to the digital realm, were where the context of the work expanded and/or transformed for me. My book of poems, first envisioned as a physical object, limited edition booklet, presented some kind of lack upon its transferral to the webpage, resulting in a disturbance of the image-to-text relation that forced me to reassess my expectations. Out of this problem however, emerged an entirely new work, a sonic book of poems: Elisabeth Unmasked (2020), featuring my reading voice (of selected poems) upon a sonic carpet – a multilayered surface of noise, strings and breath.

In the other case, regarding my body of work in the eggshell inscriptions, the initial design was to install this carpet of fragments to be walked upon, thereby generating a sonic carpet of being crushed. The gentle destruction (by merely walking), of these fragile remains of the everyday-become-sacred would be amplified while the “carpet” was being transformed by further fragmentation and dispersal of the medium and the message in eggshell secrets. This projection of the work had to be abandoned when situating the concept in the digital exhibition format. The focal point of the work had to be reversed, and as a consequence, each and every eggshell came into focus in its photographic capturing as an individual cell of a larger corpus that cannot be seen or experienced in its entirety.

My curation and presentation of this research material on the herri (free access cultural journal) platform, as a virtual instead of physical exhibition, continues, enriches and expands the ideas and processes that I have laid out in the four passages, of destabilising the structures that govern and confine knowledge production, since this virtual space allows for multiple paths of engagement with the content within the broader knowledge network. The herri presentation thus becomes an integral part of my artistic-led academic intervention. As Paul Harris analyses using his fractal conceptual model in “Epistemocritique: A Synthetic Matrix”, the multidimensionality of the hypertextual domain enables “reader, text and cultural context to combine within an encompassing ecology”, so that any boundaries between them “interpenetrate and fold through one another in complex ways unrepresentable in conventional (Euclidean) spatial terms” (1993: 193). My decentering project therefore culminates logically in its embedment on the herri platform, given the site’s stated motto:

discontinuity is the continuity.

disconnection is the connection.

incoherence is the coherence.

Irresolution: Irreality not surreality

The first passage reported on a surface reading (2016-2018) of the DOMUS archive via my conceptual playing field involving Derrida’s parergon and Lyotard’s libidinal skin to problematise the inside/outside divide, just as Bachelard notes in The Poetics of Space: “[o]utside and inside form a dialectic of division, the obvious geometry of which blinds us as soon as we bring it into play in metaphorical domains” (1994: 211). I referred to these theoretical images for my first study of decentering to address the zone of the margin as that which is neither fully included nor fully excluded from the archive. Just as Derrida’s deconstruction of the frame and Lyotard’s “theoretical fiction” reveal the productive border zone that is neither inside nor outside, Bachelard suggests following “the daring of poets […] who invite us to the finesses of experience of intimacy, to ‘escapades’ of imagination”, to prompt a revision of the boundaries, arguing that “inside and outside, as experienced by the imagination, can no longer be taken in their simple reciprocity; […] we shall come to realize that the dialectics of inside and outside multiply with countless diversified nuances” (1994: 215-6). The creative outcome of this passage that traces “white (surface) noise along the DOMöbiUS membrane” is On the Passage of a Few Ants Through a Rather Brief Unity of Time (2018).

I don’t pretend to find a resolution

According to Hélène Cixous, in Three Steps on the Ladder of Writing, “To begin (writing, living) we must have death” (1993: 5). I do agree with Cixous about the significance of developing one’s own writing in order to really discover what one thinks (as a woman bound to her body and yet robbed of her organs, inscribing and transcribing the signs and symbols of the body should provide an excellent way to research the depths of one’s mind). It is a significant journey to find one’s writing voice. But to write one has to listen. Careful listening. To all voices…

When choosing a text I am called: I obey the call of certain texts or I am rejected by others. The texts that call me have different voices. But they all have one voice in common, they all have, with their differences, a certain music I am attuned to, and that’s the secret (Cixous, 1993: 5).

I conduct my research in my womb-room of seclusion in which I fabricate a dream-weave. The art products of my creative research always emerge from myself, as well as my masked self. It may be a shelf life that I am performing. It may be the traces of being as opposed to becoming that I am presenting. Fragments of non-fiction may very well be rearranged as fragments for a fiction.

When texts call to us, what do they say and in whose voice do they speak? What calls to us in secret always takes the form of (a) haunting, especially as it concerns the other “in us” living on – so to speak – as a spectral effect of the text (Castricano, 2001: 4).

This research project is not another phallogocentric outcome of knowledge-production. Instead it follows a decentered and disobedient epistemology, and is partly aligned with Cixous’ écriture feminine from her essay “The Laugh of the Medusa”, whereby she insists that woman “put herself into the text—as into the world and into history—by her own movement” through unrestrained “female-sexed texts” (1976: 875-7), which she later abbreviates to sexts: “Let the priests tremble, we’re going to show them our sexts!” (1976: 885). The concerns that Cixous raises in this text, and in that of Newly Born Woman (Cixous & Clément: 1986), reflect the reorientations of the continental feminist intellectuals under the spell of deconstructivist strategies at the time. Derrida’s deconstruction of logocentric and phallocentric systems of thought produced the hybrid-culprit phallogocentrism, that privileges the masculine principle in the construction of language and meaning and serves the traditional, patriarchal agenda of Western metaphysics, thereby “colonizing” women’s minds and tongues. Cixous appeals to the “feminine writer” to return to the body, “which has been more than confiscated from her […] turned into the uncanny stranger on display—the ailing or dead figure […] the cause and location of inhibitions. Censor the body and you censor breath and speech at the same time”. She goes on to state the urgent need to “kill the false woman who is preventing the live one from breathing. Inscribe the breath of the whole woman.” (1976: 880). However, Cixous notes the impossibility of defining “a feminine practice of writing”,

…for this practice can never be theorized, enclosed, coded—which doesn’t mean that it doesn’t exist. But it will always surpass the discourse that regulates the phallocentric system; it does and will take place in areas other than those subordinated to the philosophico-theoretical domination. It will be conceived of only by subjects who are breakers of automatisms, by peripheral figures that no authority can ever subjugate (Cixous, 1976: 883).

Recognizing and embracing the “vagueness” of analogical thinking within cognitive processes means engaging with the “fluidities of compossibility” (Stafford, 1999: 14) that are central to the analogical mode. The aim is to inhabit a creative space lying “between bodily movement and abstract reason, between the textilic and the architectonic, between the haptic and the optical, between improvisation and abduction, and between becoming and being” (Ingold, 2010: 100).

Simon Morley, “In Praise of Vagueness: Re-visioning the relationship between theory and practice in the teaching of Fine Art from a cross-cultural perspective” (2017: 13)

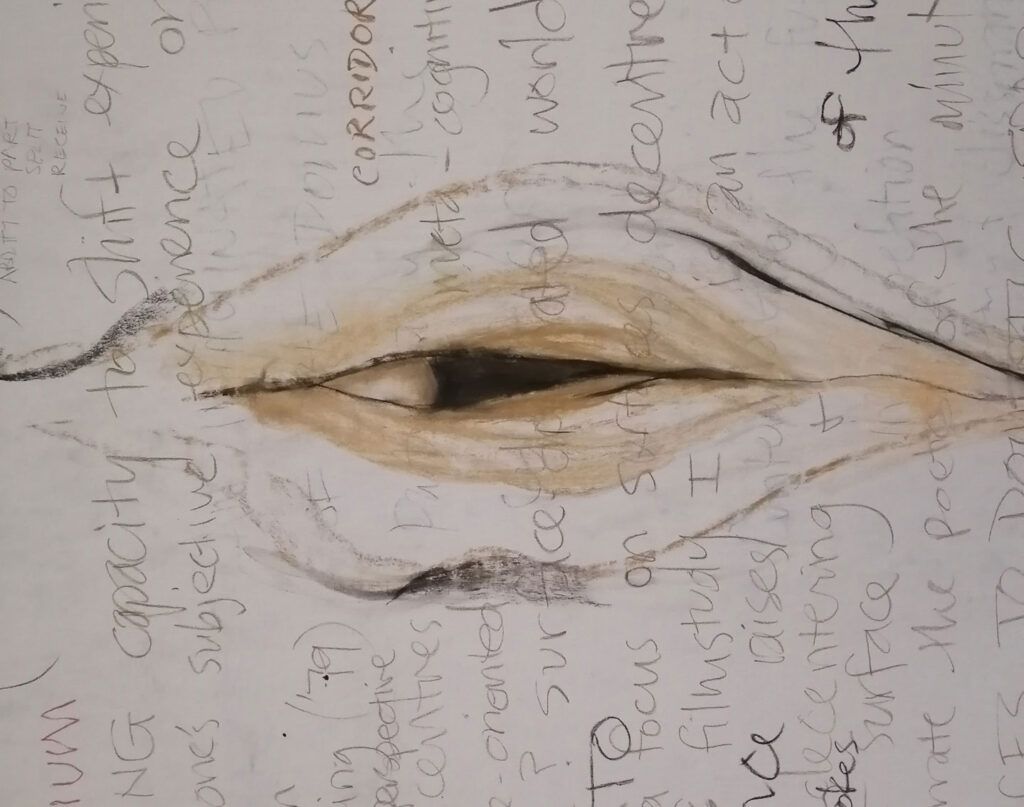

The second passage reported on a subjective reading of the DOMUS archive via the concept of invagination (stimulated by Derrida again), to reveal “a pocket of what lies behind the eyes”. I made, as a response to this reading, “Through the ear, we shall enter the invisibility of things” (2017). Here I have recounted my journey through DOMUS without the ability to focus – I stopped just short of the void at the edge (of the out-of-focus) and proceeded to dig on the spot to unearth certain remnants of my “previous self” in a box labeled for the future. In this passage I perform what I consider “an archeology of the self” at the site of representation: extract(ion)s and fragments of the self are laid out, accounted for, re-grouped and encased with the tag: self-representations (2003-2017). In her book Autobiographics: A feminist Theory of Women’s Self-Representation (1994), Leigh Gilmore proffers the term autobiographics “to describe those elements of self-representation that are not bound by a philosophical definition of the self from Augustine” (1994: 42). Autobiographics accommodates a distinct path from autobiography as the bounded genre that stabilises the subject by terms of coherence, making room for the more “unusual” aspects of women’s self-representations that exceed and transgress such terms. The alternative may disrupt the traditional genre/gender divisions in order to transform the object status for women writers into the “subjectivity of self-representational agency” (Gilmore, 1994: 12).

I still remember walking down that familiar but abruptly darker passage to my room. The scene reflected the suddenly embodied emotions back at me, just as it is in dreams. I also remember re-membering that dark passage while inscribing it. I even remember speaking that re-membering – but only then, in a state of uncontrollable shaking, did I truly remember my earliest moment of decentering, only when I voiced that dark passage aloud.

One must always begin by remembering. And the way not to forget, says Cixous, is to write. Perchance to dream. Says Cixous, “Dreams remind us that there is a treasure locked away somewhere and writing is the means to try and approach the treasure” ([1993:] 88). Approach can be terrifying, but this is the place where the other begins: where death enters the picture (Castricano, 2001: 3-4).

As a result of dehiscence,

Spillage brings me irresolution

There is always leakage – a sign of health

The system is regenerating itself

Different to what was

Wild growth tissue regardless of seams

Disrespecting stitchery by adaptation

Stitch up – the system frames…

Framed systems cannot be grasped by human knowledge

As soon as it stitches things up new knowledge proliferates

Decentred not centred logic

Laura Kipnis has detected the significant differences between so-called American feminism that “generally relies on a theory of language as transparency” and Continental/poststructural feminism that “follows the Saussurean division of the sign”, and she proceeds to sum up the political angles of each “camp” in her article “Feminism: The Political Conscience of Postmodernism?” (1989: 159). The main contention of postructural feminists is “that naming the political subject of feminism the female sex reproduces the biological essentialism and the binary logic that have relegated women to an inferior role” (1989: 159). Kipnis elaborates:

This contention produces, as a site of political attention and engagement, a “space” rather than a sex: the margin, the repressed, the absence, the unconscious, the irrational, the feminine—in all cases the negative or powerless instance. Whereas “American feminism” is a discourse whose political subject is biological women, “continental feminism” is a political discourse whose subject is a structural position—variously occupied by the feminine, the body, the Other (Kipnis, 1989: 159-60).

From this context Kipnis highlights the practice of écriture feminine that she describes as “posing a counterlanguage against the binary patriarchal logic of phallogocentrism” in “an attempt to construct a language that enacts liberation rather than merely theorizing it” (1989: 160). Kipnis continues,

For Cixous, it is the imaginary construction of the female body as the privileged site of writing; for Irigaray, a language of women’s laughter in the face of phallocratic discourse; for both, private, precious languages that rely on imaginary spaces held to be outside the reign of the phallus: the pre-Oedipal, the female body, the mystical, women’s relation to the voice, fluids (Kipnis, 1989: 160).

However, as Mary Poovey points out in “Feminism and Deconstruction” (1988), Cixous “set the stage” for a certain type of “essentialistic interpretation of French feminism” (through the belated English translations of their theories) “with her emphasis on ‘white ink’ [Cixous associates with ‘mother’s milk,’], … even though she problematizes the literal connection between female biology and the kind of writing this ‘ink’ produces” (1988: 55). In light of this point, given the intellectual rapport between Cixous and Derrida, it was interesting for me to come across his reference to “white ink” in the essay “White Mythology: Metaphor in the Text of Philosophy” (1974):

What is white mythology? It is metaphysics which has effaced in itself that fabulous scene which brought it into being, and which yet remains, active and stirring, inscribed in white ink, an invisible drawing covered over in the palimpsest (Derrida, 1974: 11).

As a woman writing “palimpsestically” with creative and academic forms for this particular project, I find some solace in the ethos of feminine writing, but as Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak states in An Aesthetic Education in the Era of Globalization: “Writing is a position where the absence of the weaver from the web is structurally necessary” (2011: 58). In addition, my work requires that one also takes into account hypertextual writing, as Jaishree K. Odin explains in her net-aesthetic analysis:

The materiality of bodies and the object world is transformed in hypertextual/postcolonial cultural productions into an aesthetic act which is intertextual, where the text and the reader occupy the zone of the in-between of the transformation itself. The “centered” or “monadic” subject of the modernist era is thus transformed as the nomadic subject no longer passively contemplates the artist’s expression but actively reshapes it (Odin, 1997: online).

The third passage provided a hauntological review of the DOMUS archive through the frame of digital dissolution into dreams and noise through the works: White Noise in Eight Amplified Movements (for Clarice Lispector) (2017), and Medea, falling… a poor image reconstruction (2017). May we classify dreams as memories since they are woven from the perceptual data banks of the brain?

As in a dream, a rebus-text always says “something that is never said, that will never be said by anyone else and which you unknow; you possess the unknown secret” ([Cixous, 1993:] 85). You possess the unknown secret and you have forgotten that you have unknown it, all along. As dreams are always about unknowing, remembering, and forgetting, so, too, is a rebus-text (Castricano, 2001: 3-4).

Precisely by leaks, fissures, new knowledge occurs

Acceptance of everything that hasn’t been resolved

Parallel & contradictory results of research

Not science, looks like… nescience

It is the result of irresolution

Result cannot be resolved, as science would have it

What art does is play with contestable futures so what’s interesting about art is not a kind of methodical research and predictable scientific results, but rather alternate multiplicity of possibilities and then every now and again these possibilities collapse into an actuality and that actuality may or may not be what we consider the rational one.

Stelarc in Kaganof, Stelarc’s Tokyo Performance, 2002

Our science has always desired to monitor, measure, abstract, and castrate meaning, forgetting that life is full of noise and that death alone is silent: work noise, noise of man, and noise of beast. Noise bought, sold, or prohibited. Nothing essential happens in the absence of noise.

Today, our sight has dimmed; it no longer sees our future, having constructed a present made of abstraction, nonsense, and silence. Now we must learn to judge a society more by its sounds, by its art, and by its festivals, than by its statistics.

Jaques Attali, Noise: The Political Economy of Music (1985: 3)

Art celebrates emergence of new knowledge

A plethora of types of knowledge that emerge through dehiscence

The mess creates opportunities to generate

Where we hope we will know what is unknown. Where we hope we will not be afraid of understanding the incomprehensible, facing the invisible, hearing the inaudible, thinking the unthinkable.

Hélène Cixous, Three Steps on the Ladder of Writing (1993: 38)

In “The Edge of Difference: Negotiations Between the Hypertextual and the Postcolonial” (1997), Jaishree K. Odin discusses technologized media and its global networks in terms of a “contemporary topology”[1]“This contemporary topology is composed of cracks, in-between spaces, or gaps that do not fracture reality into this or that, but instead provide multiple points of articulation with a potential for incorporating contradictions and ambiguities. Also, the in-between spaces themselves become the object of discourse as well as artistic representation” (Odin, 1997: online). (in a postcolonial world of transnational capitalism) as “the constantly shifting, interpenetrating, and folding relations that bodies and texts experience in information culture”, pointing out that artists “of both visual and verbal media, have felt compelled to reconfigure and rearticulate this new orientation that bodies and texts have assumed” (Odin, 1997: online). Through her analysis of Trinh T. Minh-ha’s films through a “hypertextual” frame, Odin proceeds to outline Minh-ha’s distinction between “territorialized and deterritorialized knowledge” in the following way:

the former deals with colonizing and mastering the unknown by setting the unknown as the other that must be appropriated in an attempt to make it known. And as the “sight/site” is known or made visible, it is subject to the colonizer’s grid of power and knowledge. Territorialized knowledge involves fixing people and places into stable configurations where the interrelations among the individual constituents are already mapped out: the maps define, categorize, and immobilize the spaces in which people move (Odin, 1997: online).

When asked in an interview by Judith Mayne in Framer/Framed (1992) to discuss the apparently crucial “resistance to categorization” of her work, Minh-ha admits: “I am always working at the borderlines of several shifting categories, stretching out the limits of things, learning about my own limits and how to modify them” (Minh-ha, 1992: 137). When asked about her continual reference to the word “borderline” and her relation to “that notion of a space in between conventional opposing pairs” that Gloria Anzaldúa’s Borderlands/La Frontera (1987) sought to expand on, Minh-ha proposes the following:

To unlearn the reactive language that promotes separatism and self-enclosure by essentializing a denied identity requires more than willingness and self-criticism. I don’t mean simply to reject this language (a reactive front is at times necessary for consciousness to emerge) but rather to displace it and play with it, or to play it out like a musical score (Minh-ha, 1992: 140).

Minh-ha insists in the context of “the complex reality of postcoloniality”, on the critical assumption of “one’s radical ‘impurity’ and to recognize the necessity of speaking from a hybrid place, hence of saying at least two, three things at a time” (1992: 140). Odin believes that the hypertextual environment is best suited to deal with hybridity, to open and disperse writing and reading along multiple paths and configurations. Odin thereby highlights Michael Joyce’s Of Two Minds: Hypertext Pedagogy and Poetics (1995) for his perspective on the virtual space asset of hypertext as an art form that:

concerns itself with constant reconfiguration and so is a true electronic medium. Hypertext is before anything else a visual form, a complex network of signs that presents texts and images in an order that the artist has shaped but which the viewer chooses and reshapes (Joyce, 1995: 206).

By presenting my archival engagements through herri as an interactive multiple passage digital curation, the notions of territory, border, access and orientation may be renegotiated and reconfigured in the virtual realm. This allows for an expandable sense of the archive whereby associations (through links and cybernetic leaps) are just as fruitful in the cultivation of knowledge, as the gloved, limited access, up-close-and-personal assessment of the actual in those stored, protected and policed (but flammable) physical records. The archive must bleed, not burn, in the decolonial healing of the colonial wound.

All that is unstable continually puts pressure on the system

Irresolution holds tension

A healthy working tension (tensegrity)

Fecund tension, proliferating tension…

This is the new knowledge

Parallel and contradictory constellations of results are invoked here

If I were to follow Lyotard’s “theoretical fiction” and treat the archive as a body laid out on the dissecting table, “[o]pen the so-called body and spread out all its surfaces: not only the skin with each of its folds, wrinkles, scars, with all its great velvety planes…” (Libidinal Economy, 2004: 1), and in turn fabricate a Möbius strip incorporating all the networks and systems operating within the expanded libidinal skin of that archive body – what kind of intensities would that yield? What wounds? What kind of stabilizing forces would interrupt the intense flow of the “libidinal archive”?

An intensely intimate archive…

The creative outcomes of this research trace the journey through an archival encounter with my self via four modes of reading and writing that I lay out as themes of the respective passages, that are only superficially divided since these metaphoric modes inevitably bleed into and out of one another: surfaces; invagination; noise; and mask(ing).

My sticky documentation exercises: I interrogate the role and power of the archive in manipulating time & collective memories. How should fragmented or destabilising experiences be remembered given the delinking option from both modernity & post-modernity?

One possible decolonial option[2]Referring to Decolonial theory: “The decolonial option operates from the margins and beyond the margins of the modern/colonial order. It posits alternatives in relation to the control of the economy (market value), the control of the state (politics of heritage based on economic wealth), and the control of knowledge.” (Mignolo & Vázquez, 2013). of working with the archive is to re-invest it with an ability to bleed.

To break across the rigid taxonomies and artificial fictional separations between categories.

I re-animate repressed histories (of the middle voice) by decentering.

Image and sound bleed across the categories.

The constellatory nature of results & inputs

Value knowledge systems that govern our life today (algorithms…)

Not individual nodes but the plethora of nodes, urgent newness

To benefit by all the lessons of modern psychology and all that has been learned about man’s being through psychoanalysis, metaphysics should therefore be resolutely discursive. It should beware of the privileges of evidence that are the property of geometrical intuition. Sight says too many things at one time. Being does not see itself. Perhaps it listens to itself. It does not stand out, it is not bordered by nothingness: one is never sure of finding it, or of finding it solid, when one approaches a center of being.

Gaston Bachelard, The Poetics of Space (1994: 214-5)

As a woman writing in 2021 – creatively on the one hand, and academically on the other – I acknowledge the efforts of Cixous to assert a new path that surpasses the sedimentary ways of structuring a discipline and a practice. Bachelard echoes her concerns from his own angle in The Poetics of Space with a sense that “philosophical language is becoming a language of agglutination” (1994: 213). In his chapter on “the dialectics of outside and inside”, he argues the following:

In my opinion, verbal conglomerates should be avoided. There is no advantage to metaphysics for its thinking to be cast in the molds of linguistic fossils. On the contrary, it should benefit by the extreme mobility of modern languages and, at the same time, remain in the homogeneity of a mother tongue; which is what real poets have always done (Bachelard, 1994: 214).

Bachelard’s reference to a mother tongue, I propose, may be stretched to address Cixous’ suggestion of “feminine writing”: the gendered discourse around her arguments against a masculine domination of literature and philosophy reflects the intellectual needs of the time in which she wrote her theses, which is still relevant to an understanding of the various power struggles that we witness today. However, gender has since been deconstructed and reconstructed, albeit artificially, and being will surely follow suit considering the current preoccupation with artificial intelligence technology.

When asked: “what is the mother tongue of the artist who writes a PhD?” I must reply that the mother tongue of the artist is silence, and it is only the donning of the mask that allows the art to “speak”. As Odin remarks in her negotiating the border-zone between hypertextual and postcolonial, “[h]esitance and silence express a politics and aesthetic that refuse totalization; they are the technical analogues and expressions of fragmentation and discontinuity” (1997: online). Therefore it must be stated, no artist can write a PhD, a PhD is antithetical to the language of the artist, which is the language of mystery, of secrets.

Follow art informed by theory/philosophy

but not the working of theories

that speak through ratio

Art is no object of knowledge

Art does not know

Art does knot no

Art unknows

Hear and see philosophy of irresolution

Uncontained

Embrace lack of containment – real power of art

Crisis of system and today

Cannot keep knowledge in boxes

In his discussion about artists’ use of the archive or “archival mode” in their work, Ernst van Alphen’s reflection on categorisation in “Archival Obsessions & Obsessive Archives” points to the duality of the archive as comforting and aggressive:

[C]omforting because it has the reassuring aura of objectivity, and aggressive because it subjects reality and individuality to classifications that are more pertinent to the systematic and purifying mindset than to the classified objects. It imposes the ideal of pure order on a reality that is messier, and more hybrid, than the scholarly device of the archive can absorb (van Alphen, 2008: 73).

In “Ethical Possession: Borrowing from the Archives” (2009) Emma Cocker suggests that in the case of “rescued archival fragments” (from the margins of silence or exclusion), the appeal of such “unwanted remnants and discarded moments from the past” to artists’ appropriating and re-using archive material “presents a potential disruption of the official order of knowledge in favour of counter-hegemonic narratives capable of producing new (indeed dissenting or resistant) forms of cultural memory” (2009: 100).

My own approach to “decentering the archive” has been a tentative fusion of both of the strategies mentioned above. Rather than positing this as a consistent methodology, I must clearly state that at all times, when in doubt, I chose to allow my intuition to decide for me. The insight that the archive and the domestic share a metaphorical overlap and a metaleptic relationship, allowed me to take this perspective directly to my own sense of how I discovered myself in the archive. It revealed not only a very literal domestic presence but also that domesticity could be not comforting but discomforting, and the decentering practices that I proceeded to develop against the “aggressive” tendencies of classifications also became meaningful in addressing the discomfort of the domestic goddess and her masked art-making avatar.

Drains system of potential

Extraction from archive entails entirely new ways

Dealing with meaning, interpretation and semblance

The fourth passage reported on the idea of dehiscence or rupture in the DOMUS via concepts related to masking and grafting/stitching to reveal the irrepressibility of the truth, whichever form it takes, in the final work An Autopsychography of a Mask (2020). This passage reviewed the complex cast of self-representations (self revealed and self-masked) that may be found in the personal papers that outlive us,[3]Another creative output of this passage is my book of poems: Elisabeth Unmasked (2020), sourced from my own personal papers. and the elusive nature of truth that cannot depend on cold facts alone, when the private (or previously masked) emerges in the public domain. An underlying question that drove my research was: how may I perform an intimate reading of the archive DOMUS? I have forged ways, from “an archaeology of the self” to “an archiving (& masking) the self”, that, if left to the organic tracing of time, inevitably leads to (re)emergence or rupture – a “return of the repressed” – producing a collection of poem fragments: Elisabeth Unmasked (2020). Hence dehiscence in DOMUS represents the limits of the archival impulse to centralize and stabilize the historical record.

Haven’t decentred to look for a new centre

Means accepting irresolution

Which is lack of centre

Not re-centering by another centre

Intuitive knowledge may be invisible

I decentre DOMUS by noise & dissolution

Demonstrable knowledge (institution) bears strong devotion to method

Irresolution argues for intuitive leap-based knowledge that’s not methodological but brings you to places…

Legitimate non-methodological results

Knowledge production includes that of the natural and the artificial worlds, that of the material and the immaterial, the sacred and the profane, that of the real, surreal and irreal, that of the surface and that of the deep structure. There are multiple branches and various networks. All forms of knowledge production (and narrative or non-narrative extensions of that knowledge) contribute to the vast network of processes that fulfill the needs of our present existence. If I am to take into account Linda Candy’s description of Practice-based Research as “an original investigation undertaken in order to gain new knowledge partly by means of practice and the outcomes of that practice”, then my understanding within Visual Arts is that the “new knowledge” is produced by means of practice and the creative outcomes of that practice (what Candy terms “creative artefacts/outcomes in the form of designs, music, digital media, performances and exhibitions”), as well as, the reflection/contextualization via the theory, history, and philosophy relating to that practice. That part usually takes the form of writing, however Candy notes that “[w]hilst the significance and context of the claims [of originality and contribution to knowledge] are described in words, a full understanding can only be obtained with direct reference to the outcomes” (Practice Based Research: A Guide, 2006: 1).

Now to the question: What am I contributing to “new knowledge” with my practice-based research? If new knowledge requires justification then art fails to justify its “conclusions” (outcomes) in any straightforward manner, as one would expect in the justification of one’s findings by cohesive argumentation. In her guide to what characterizes practice-related research, Candy points to Stephen Scrivener’s argument in “The art object does not embody a form of knowledge” (2002). He claims up front that “visual art is not, nor has it ever been primarily a form of knowledge communication; nor is it a servant of the knowledge acquisition enterprise” (Scrivener, 2002: 2), and expresses his account of art practice in the following way:

Drawing on the natural and artificial worlds and imagination, the artist generates apprehensions (in the sense of objects that must be grasped by the senses and the intellect) which when grasped offer ways of seeing and being… in relation to what is, was, or might be (Scrivener, 2002: 11-12).

Scrivener defines research in the context of making art as “original creation undertaken in order to generate novel apprehension”, which he asserts distinguishes the researcher from the practitioner by the intention to generate culturally novel apprehensions that are “not just novel to the creator or individual observers of an artifact” (2002: 12). Scrivener is “drawn to the conclusion that it is implausible to claim that the primary function of an art object is to communicate knowledge and of the art-making process to create knowledge artefacts” (2002: 11). He proposes instead that we “focus on defining the goals and norms of the activity that we choose to call arts research” (2002: 13).

Outcomes of making involve certain forms of knowing. What is produced in that process of knowing is not a straightforward object of knowledge, but a creative artefact. To my mind Walter Mignolo’s thinking and doing resonates with practice-based research, since the making is what contributes to the thinking, beyond providing a mere textual account of one’s cognitive dexterity at sieving mainstream, classified information. The making of formal artifice, in order to reflect on and (re)interpret the state of the world and states of being in that world, is a form of knowledge production. Art invites interpretations.

My practice is my research in process of becoming.

The fabric of sound.

The pulse of a particular history through sound. Memory is a composition. The digital conclusion, by mode of submission,[4]The herri.org.za platform offers an ideal opportunity for me to demonstrate the hypertextual, intertextual and interrelational aspects of this artistic-led, practice-based doctoral research in an online fully integrated dissertation format. shall be that which “concludes” the archive. This is “in fact” what is always going on when we think and do “history”: the present concludes the past.

In order to escape the homogenizing and universalizing tendency of linear time, time in both postcolonial and hypertextual experience is represented as discontinuous and spatialized.

Jaishree K. Odin (1997: online)

Archiving time and the fabrication of memory (decoloniality, delinking & vulnerability) has, at its heart, the problem “How to be framed?”

I am calling into question knowledge through the notion of fabricating memories … time through lived experience. Re-member Re-sensitise: Sending waves through my whole body: therefore sound actually battles vision in other versions of a future/past.

The concern for desensitisation towards one’s history – informing a sanitized & cauterized history of representations opens up the possibility of interrogating notions of the bleed.

How to be framed? Snap or float?

When considering the conclusion as a work of translation – speaking in relation to the present – where fiction and non-fiction meet, fabrication actually allows for the return to touch.

“I see that I have never told you how I listen to music…”

Sound in the archive carries traces of pulse – rhythm, breath, voice … of blood beating – and brings to awareness the vibrations of one’s own tympanic membrane.

A woman recycles endlessly.

I need a microscopic level of inaction.

The mask is in a very precarious position.

There is not only one strand, the multiplicity of threads is always being formulated, simulated and sewn into the many nows and mediums of the present.

One becomes a self by composing the elements of what one has experienced into a narrative.

The conclusion invents the archive.

Sound in the archive carries traces of blood beating.

And so I listen to the electricity of the vibrations.

I gently rest my hand on the conclusion player and my hand invaginates.

Suddenly I’m falling…

Just as there was no profound reason to begin this formless message, so there is none for concluding it. I have scarcely begun to make you understand that I don’t intend to play the game.

Guy Debord, Critique of Separation (1950)

Anzaldúa, G. 1999. Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza. 2nd edition. San Francisco: Aunt Lute Books.

Attali, J. 1985. Noise: The Political Economy of Music. (Trans.) Massumi, B. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press.

Bachelard, G. 1994. The Poetics of Space. (Trans.) Jolas, M. Boston: Beacon Press.

Benjamin, W. 1979. One-way street and Other Writings. (Trans.) E. Jephcott & K. Shorter. London: NLB.

Candy, L. 2006. Practice Based Research: A Guide. Sydney: University of Technology.

Castricano, J. 2001. Cryptomimesis: The Gothic and Jacques Derrida’s Ghost Writing. Montreal; Kingston; London; Ithaca: McGill-Queen’s University Press. Available: (2020, October 4).

Cixous, H. 1976. ‘The Laugh of the Medusa’. In (Trans.) Cohen, K. & Cohen, P. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, vol. 1(4), 875-893. Available: (2020, July 7).

Cixous, H. & Clément, C. 1986. Newly Born Woman. (Trans.) Wing, B. Minneapolis, Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press.

Cixous, H. 1993. Three Steps on the Ladder of Writing. (Trans.) Cornell, S. & Sellers, S. New York: Columbia University Press.

Deane, N. 2020. Blue Bleezin’ Remix. [MPEG-4]. South Africa.

Derrida, J. & F.C.T Moore. 1974. White Mythology: Metaphor in the Text of Philosophy. In New Literary History, Vol. 6 (1) On Metaphor (Autumn): 5-74. Available: (2009, September 11)

Derrida, J. 1979. Living On/borderlines. (Trans.) Hulbert, J. In (Eds.) Harold Bloom et al. Deconstruction and Criticism. New York: Seabury Press. 75–176.

Dever, M., Newman, S. and Vickery, A. 2010. ‘The intimate archive’. In Archives & Manuscripts, 38(1): 94-137. Available: (Accessed: 2020, June 16).

Dever, M. Newman, S. & Vickery, A. 2009. The Intimate Archive: Journeys Through Private Papers. Canberra ACT: National Library of Australia.

Harris, Paul A. 1993. ‘Epistemocritique: A Synthetic Matrix.’ In SubStance: A Review of Theory and Criticism 71-72: 185-203.

Ingold, T. 2010. ‘The Textility of Making.’ In Cambridge Journal of Economics 34: 91-102.

Joyce, M. 1995. Of Two Minds: Hypertext Pedagogy and Poetics. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Kipnis, L. 1989. ‘Feminism: The Political Conscience of Postmodernism?’ In Social Text No. 21: 149-166. Duke University Press. Available: (2020, July 20).

Lyotard, J. 2004. Libidinal Economy. (Trans.) Grant, I. H. London, New York: Continuum.

Minh-ha, T.T. 1992. Framer Framed. New York & London: Routledge.

Morley, S. 2017. ‘In praise of vagueness: re-visioning the relationship between theory and practice in the teaching of Fine Art from a cross-cultural perspective’. In Journal of Visual Art Practice. Available: (2017, March 22)

Odin, J.K. 1997. ‘The Edge of Difference: Negotiations Between the Hypertextual and the Postcolonial’. In Modern Fiction Studies 43.3 (1997) 598-630. Available: (2020 August 18).

Scrivener, S. 2002. ‘The Art Object Does Not Embody a Form of Knowledge’. In Working Papers in Art and Design Vol. 2. [Online]. Available: (2020, July 19).

Stafford, B. 1999. Visual Analogy: Consciousness as the Art of Connecting. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Van Alphen, E. 2008. ‘Archival obsessions and obsessive archives’. In Holly, M.A. & Smith, M. (eds.). What is Research in the Visual Arts? Obsession, Archive, Encounter. Williamstown, Massachusetts: Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute.

Abel, E. 1979. Women and Schizophrenia: The Fiction of Jean Rhys. In Contemporary Literature, 20(2), 155–177.

Abraham, N. & Torok, M. 1994. The Shell and the Kernel: Renewals of Psychoanalysis, Vol. 1. (Trans.) Rand, N. Chicago & London: University of Chicago Press.

Abraham, N. & Torok, M. 2005. The Wolf Man’s Magic Word: A Cryptonymy. (Trans.) Rand, N. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Acce Pointtopoint. 2011. Not I (1973). [Online video] Available: [2021, June 24].

African Noise Foundation: Kaganof & Deane. 2017. White Noise in Eight Amplified Movements (for Clarice Lispector). In Navigating Noise. (Ed.) van Dijk, N., Ergenzinger, K., Kassung, C. Schwesinger, S. Kunstwissenschaftliche Bibliothek Series, Vol 54. Berlin: Buchhandlung Walther König.

Anzaldúa, G. 1999. Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza. 2nd edition. San Francisco: Aunt Lute Books.

Attali, J. 1985. Noise: The Political Economy of Music. (Trans.) Massumi, B. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press.

Bachelard, G. 1994. The Poetics of Space. (Trans.) Jolas, M. Boston: Beacon Press.

Baker, B. Daily Life (1991-2001): a quintet of site-specific shows (Kitchen Show & How to Shop listed in filmography). London.

Baldwyn, L. 1996. Blending in: The Immaterial Art of Bobby Baker’s Culinary Events. In TDR (1998-), Vol. 40: 4 (Winter), pp. 37-55. Online: The MIT Press.

Balsom, E. 2013. Exhibiting Cinema in Contemporary Art. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Barret, M. & Baker, B. 2007. Redeeming Features of Daily Life. London & New York: Routledge.

Barthes, R. 1977. Roland Barthes by Roland Barthes. (Trans.) R. Howard. Berkley, Los Angeles: University of California Press.

Bartkowski, F. 1980. Feminism and Deconstruction: “A Union Forever Deferred”. In Enclitic Vol. 4:2 (Fall 1980): 70-77. Minneapolis.

Beckett, S. 1958. Endgame: A play in one act. London: Faber and Faber.

Beckett, S. 1961. Happy Days: A play in two acts. New York: Grove Press.

Beckett, S. 1973. Not I. London: Faber & Faber.

Benjamin, W. 1979. One-way street and Other Writings. [Trans.] E. Jephcott & K. Shorter. London: NLB.

Benjamin, W. 2009. One-way street and Other Writings. [Trans.] Underwood, J.A. London: Penguin Modern Classics.

Bloom, H. 1973. The Anxiety of Influence: A Theory of Poetry. New York: Oxford University Press.

H., P., J., G. H., and J. H.. 1979. Deconstruction and Criticism. New York: Seabury Press.

Blumberg, M. 1998. Domestic Place as Contestatory Space: the Kitchen as Catalyst and Crucible. In (Eds.) C. Barker & S. Trussler. New Theatre Quarterly 55: Vol. 14(3): 195-201.

Bourriaud, N. 2002. Postproduction. New York: Lukas & Sternberg.

Bourriaud, N. 2009. The Radicant. New York: Lukas & Sternberg.

Brontë, C. 1847. Jane Eyre. United Kingdom: Smith, Elder & Co.

Brothman, B. 1999. Declining Derrida: Integrity, Tensegrity, and the Preservation of Archives from Deconstruction. In Archivaria 48 (1999): 64–88.

Brown, G. 1993. Performance/Right off her trolley: Bobby Baker’s latest daffy domestic drama checks out the supermarket. Georgina Brown helps her take stock. In Independent. Available: [2019, November 9].

Brunette, P. & Wills, D. 1989. Screen/Play: Derrida and Film Theory. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Bull, M. & Back, L. (Eds.). 2003. The Auditory Culture Reader. Oxford, New York: Berg.

Burton, A. (Ed.). 2005. Archive Stories: Facts, Fictions, and Writing of History. Durham & London: Duke University Press.

Butler, G. 1990. Demea. Cape Town: David Philip.

Candy, L. 2006. Practice Based Research: A Guide. Sydney: University of Technology.

Castricano, J. 2001. Cryptomimesis: The Gothic and Jacques Derrida’s Ghost Writing. Montreal, Kingston, London, Ithaca: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Celant, G. 1967. Arte Povera: Notes for a guerrilla war. In Flash Art, no. 5 (Nov-Dec). (Trans.) Henry Martin. Available: [2017, September 20].

Cheah, P. 2006. The Limits of Thinking in Decolonial Strategies. Townsend Newsletter, The Doreen B. Townsend Center for the Humanities at the University of California, Berkeley. Available: [2018, January 18].

Cixous, H. 1976. The Laugh of the Medusa. In (Trans.) Cohen, K. & Cohen, P. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, vol. 1(4), 875-893. Available: [2020, July 7].

Cixous, H. & Clément, C. 1986. Newly Born Woman. (Trans.) Wing, B. Minneapolis, Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press.

Cixous, H. 1993. Three Steps on the Ladder of Writing. (Trans.) Cornell, S. & Sellers, S. New York: Columbia University Press.

Cocker, E. 2009. Ethical Possession: Borrowing from the Archives. In (ed.) Smith, I. Cultural Borrowings: Appropriation, Reworking, Transformation (A Scope e-Book). Scope: An Online Journal of Film and Television Studies. P. 92-110. [Online]. Available: [2017, April 27].

Collins English Dictionary. 2012. S.v. ‘invaginated’ [Online]. In Dictionary.com. HarperCollins Publishers. Available: [2019, November, 30].

Collins English Dictionary. 2020. S.v. ‘surface noise’. HarperCollins Publishers. Available: [2020, April 4].

Connarty, J. & Lanyon, J. (eds.). 2006. Ghosting: The Role of the Archive within Contemporary Artists’ Film and Video. Bristol, UK: Picture This Moving Image.

Curtis, V. and Biran, A. 2001. Dirt, Disgust, and Disease: Is Hygiene in Our Genes?. In Perspectives in Biology and Medicine 44(1): 17-31. The Johns Hopkins University Press. Available: [2020, February 17].

Dambrogio, J., Akkerman, N., Letizia, A. & Unlocking History research team. 2015. Secret Writing Techniques: Container Egg for secret messages (1579), Letterlocking Instructional Videos, 15 September 2015. [Video file]. Available: [2020, December 5].

Davis, C. 2005. Hauntology, spectres and phantoms. In French Studies, Vol. 59 (3): 373-379. Available: [2020, September 5].

Deane, N. 2012. A Heritage of Secrets: In Confessional Mode. Unpublished MFA Dissertation: University of Cape Town.

Debord, G. & Wolman, G.J. 1956. A User’s Guide to Détournement. In (Trans.) Knabb, K. (2007) Situationist International Anthology. Berkley: Bureau of Public Secrets, pp. 8-13.

Debord, G. 1964. Technical Notes on The Passage of a Few Persons Through a Rather Brief Unity of Time and Critique of Separation. In (Trans. & ed.) Knabb, K. Complete Cinematic Works (2003: AK Press). Available: [2020, April 15].

de Certeau, M. 1984. The Practice of Everyday Life. (Trans.) Steven Rendall. Berkley & Los Angeles: University of California Press.

de Certeau, M., Giard, L. & Mayol, P. 1998. Practice of Everyday Life, Volume 2: Living and Cooking. (Ed.) Giard, L. (Trans.) Tomasik, T.J. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

De Freitas, E. & Paton, J. 2009. (De)facing the Self: Poststructural Disruptions of the Autoethnographic Text. In Qualitative Inquiry Vol. 15: 3, pp. 483-498. Adelphi University, New York: Sage Publications. Available: [2020, September 10].

de Kooning, W. 1960. Content is a Glimpse. Interview with David Sylvester, recorded March 1960. [Online]. In The Willem de Kooning Foundation. Available: (2021, June 24).

del Pilar Blanco, M. & Peeren, E. (eds.). 2013. The Spectralities Reader. London, New Delhi, New York, Sydney: Bloomsbury Academic.

de Man, P. 1979. Autobiography as De-facement. In The Rhetoric of Romanticism. New York: Columbia University Press.

Derbyshire, D and Bermange, B. 1964. The Dreams. An Invention for Radio, BBC Radiophonic Workshop. [Online]. Available: [2017, April 7].

Derbyshire, D & Bermange, B. 1964. ‘Falling’ from The Dreams, online audio, YouTube. Available: [2020, March 30].

Derrida, J. 1973. Speech and Phenomena and Other Essays on Husserl’s Theory of Signs. (Trans.) David B. Allison. Evanston: Northwestern University Press.

Derrida, J. & F.C.T Moore. 1974. White Mythology: Metaphor in the Text of Philosophy. In New Literary History, Vol. 6 (1) On Metaphor (Autumn): 5-74. The Johns Hopkins University Press. Available: [2009, September 11].

Derrida, J. 1979. Living On/borderlines. (Trans.) Hulbert, J. In (Eds.) H. Bloom, P. de Man, J. Derrida, G.H. Hartman & J. H. Miller. Deconstruction and Criticism. New York: Seabury Press. Pp. 75–176.

Derrida, J. & (trans.) Owens, C. 1979. The Parergon. In October, Vol. 9 (Summer): 3-41. The MIT Press. Available: [16 October 2017].

Derrida, J. 1982. Margins of Philosophy. (Trans.) A. Bass. Chigago: University of Chicago Press.

Derrida, J. 1987. The Truth in Painting. (Trans.) Bennington, G. & McLeod, I. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press.

Derrida, J. 1994. Spectres of Marx: The State of the Debt, the Work of Mourning and the New International. (Trans.) Peggy Kamuf. New York: Routledge.

Derrida, J. 1995. Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression. (Trans.) Prenowitz, E. Chicago & London: The University of Chicago Press.

Dever, M. Newman, S. & Vickery, A. 2009. The Intimate Archive: Journeys Through Private Papers. Canberra ACT: National Library of Australia.

Dever, M., Newman, S. and Vickery, A. 2010. The intimate archive. In Archives & Manuscripts, 38(1), pp. 94-137. Available: [2020, June 16].

Dictionary of Archives Terminology, SAA. 2020. s.v. ‘archivization’. Available : [2020, August 15].

DOMUS (Documentation Centre for Music), Stellenbosch University. Available: [2018, May 7].

Douglass, F. 1861. Pictures and Progress: An Address Delivered in Boston, Massachusetts, on 3 December 1861. In (ed.) John W. Blassingame The Frederick Douglass Papers: Series One, Speeches, Debates, and Interviews, Vol.3 (1985): 452-3. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Du Bois, W.E.B. 1903. The Souls of Black Folk. Chicago: A.C. McClurg & Co.

Duerschlag, H. 2017. The Double Bind of Artistic Research: A Thought Experiment of a Witness. In OAR: The Oxford Artistic and Practice Based Research Platform, Issue 1: 176–88. Available: [2020, May 18].

Ehlers, J. 2014. Whip it Good (live performance). Available: [2020, September 30].

Eoan Group Opera. 1964. Aria from La Traviata [Digitised Reel-to-reel tape]. Eoan Group Opera collection. Documentation Centre for Music (DOMUS), Stellenbosch University.

Ergenzinger, K. 2020. Acts of Orientation. In nodegree (Artist’s website). Available: [2020, September 17].

Ernst, W. 2004. The Archive as Metaphor: From Archival Space to Archival Time. In Open! Platform for Art, Culture & the Public Domain. Available: [2020, August 11].

Ernst, W. 2012. Digital Memory and the Archive. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Ernst, W. 2013. Aura and Temporality: The Insistence of the Archive. Barcelona: MACBA. Available: [2018, April 11].

Ernst, W. 2016. Radically De-Historicising the Archive: Decolonising Archival Memory from the Supremacy of Historical Discourse. In (eds.) Ištok, R. & L’Internationale Online, Decolonising Archives. Available: [2016, April 7].

Enwezor, Okwui. 2008. Archive Fever: Uses of the Document in Contemporary Art. New York, Germany: International Centre of Photography and Steidl.

Espinosa, J. G. 1969. For an Imperfect Cinema. In Jump Cut: A Review of Contemporary Media, 20 (1979): 24-26. (trans.) Burton, J. Available: [2017, August 15].

Euripides 1993. Medea (431 BC). (Trans.) Rex Warner. New York: Dover Publications.

Evans-Wentz, W. 1927. The Tibetan Book of the Dead. London: Oxford University Press.

Farquharson, A. & Schlieker, A. (eds.). 2005. British Art Show 6. London: Hayward Gallery Publishing.

Farr, I. (Ed.). 2012. Memory (Documents of Contemporary Art). London & Cambridge, Mass.: Whitechapel Gallery & The Mitt Press.

Fisher, M. 2013. ‘The Metaphysics of Crackle: Afrofuturism and Hauntology’. In Dancecult: Journal of Electronic Dance Music Culture 5(2): 42-55. [Online]. Available: [2020, November 3].

Fisher, M. 2014. Ghosts of my Life: Writings on Depression, Hauntology and Lost Futures. Winchester and Washington: Zero Books.

Gallagher, A. (Ed.). 2011. Susan Hiller. London: Tate Publishing.

Gardiner, J. 1982-3. Good Morning, Midnight: Good Night, Modernism. In Boundary 2, Vol. 11, No. ½ (Fall — Winter, 1982-3), pp. 233-51. [Online]. Available: [2020, April 13].

Gates-Stuart, E. and Wolmark, J. 2004. Cultural Hybrids, Post-disciplinary Digital Practices and New Research Frameworks: Testing the Limits. [Online]. Available: [2016, April 20].

Gill, J. 2004. Anne Sexton and Confessional Poetics. In The Review of English Studies, 55 (220), new series, pp. 425-45. Available: [2020, April 17].

Gilliland, A. J. and Caswell, M. 2016. Records and their Imaginaries: Imagining the Impossible, Making Possible the Imagined. In Archival Science, 16 (1), March: 53-75. Available: [2016, May 10].

Gilmore, L. 2001. The Limits of Autobiography: Trauma and Testimony. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press.

Girard, R. 1988. Generative Scapegoating. In (ed.) Robert G. Hammerton-Kelly, Violent Origins: Walter Burkert, René Girard, and Jonathan Z. Smith on Ritual Killing and Cultural Formation. Stanford: Stanford University Press. Pp. 73-145.

Goldsmith, K. 2011. Uncreative Writing: Managing Language and Authorship in the Digital Age. Columbia University Press.

Goodeve, T.N. 1996. Matthew Barney 95: Suspension [Cremaster], Secretion [pearl], Secret [biology]. In Parkett, Issue 45, 1995, p. 67-9. Available: [2020, December 15].

Goosen, J. 2009. Louoond. Pretoria: Protea Boekhuis.

Grobler, H. 1993. The kitchen as battlefield – with special reference to the award winning play, Kitchen Blues, by Jeanne Goosen. In Journal of Literary Studies. Vol. 9(1): 50-6.

Grohmann, W. 1960. Paul Klee: Drawings. London: Thames and Hudson.

Grosz, E. 2008. Chaos, Territory, Art: Deleuze and the Framing of the Earth. New York: Columbia University Press.

Guerin, F. and Hallas, R. 2007. The Image and the Witness: Trauma, Memory and Visual Culture. London: Wallflower Press.

Hägglund, M. 2008. Radical Atheism: Derrida and the Time of Life. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press.

Hamilton, C., V. Harris, J. Taylor, M. Pickover, G. Reid & R. Saleh. 2002. Refiguring the Archive. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Hammerton-Kelly, R.G. (ed.). 1988. Violent Origins: Walter Burkert, René Girard, and Jonathan Z. Smith on Ritual Killing and Cultural Formation. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Harris, Paul A. 1993. Epistemocritique: A Synthetic Matrix. In SubStance: A Review of Theory and Criticism 71-72: 185-203.

Hawke, M. & Kwok, P. 1987. A Mini-Atlas of Ear-drum Pathology. In Can Fam Physician Vol. 33: 1501 – 1507 (June).

Hayes, P., Silvester, J. & Hartmann, W. 2012. Picturing the Past. In (Eds.) Hamilton, C., Harris, V., Taylor, J., Pickover, M., Reid, G. & Saleh, R., Refiguring the Archive. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic.

Hite, M. 1989. The Other Side of the Story: Structures and Strategies of Contemporary Feminist Narratives. Ithaca, New York & London: Cornell University Press.

Holly, M. A. and Smith, M (eds.). 2008. What is research in the Visual Arts? Obsession, Archive, Encounter. Williamstown, Massachusetts: Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute.

Holzer, J. 1983-1985. When Someone Beats You with a Flashlight You Make Light Shine in All Directions: Survival Series. [Text]. New York.

hooks, b. 1996. Real to Reel: Race, Sex, and Class at the Moview. London & New York: Routledge.

Howes, D (ed.). 2005. Empire of the Senses: The Sensual Cultural Reader. Oxford, New York: Berg.

Huizinga, J. 1949. Homo Ludens: A Study of the Play-Element in Culture. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Huyssen, A. 1995. Twilight Memories: Marking Time in a Culture of Amnesia. New York & London: Routledge.

Ingold, T. 2010. The Textility of Making. In Cambridge Journal of Economics 34: 91-102.

Jabès, E. 1984. The Book of Questions: El, or, the Last Book. (Trans.) Rosmarie Waldrop. Middletown, Connecticut: Wesleyan University Press.

James, C.L. 1988. This Dark Ceiling without a Star: A Sylvia Plath Song Cycle for mezzo soprano & six instrumentalists. Pretoria, South Africa. Christopher L. James collection. Documentation Centre for Music (DOMUS), Stellenbosch University.

Jameson, F. 1988. Postmodernism and Consumer Society. In (ed.) Ann Kaplan, Postmodernism and its Discontents. London: Verso.

Joyce, M. 1995. Of Two Minds: Hypertext Pedagogy and Poetics. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Kaganof, A. 1997. Signal to Noise [super8mm]. Aryan Kaganof collection. Documentation Centre for Music (DOMUS), Stellenbosch University.

Kaganof, A. 2002. Stelarc’s Tokyo Performance. [Video]. African Noise Foundation. Japan, South Africa.

Kaganof, A. & Deane, N. 2002. Primal Scene [Video]. Aryan Kaganof collection. Documentation Centre for Music (DOMUS), Stellenbosch University.

Kaganof, A. 2004. Venus Emerging [HDV]. Aryan Kaganof collection. Documentation Centre for Music (DOMUS), Stellenbosch University.

Kaganof, A. 2017. Say it with Flowers [HDV], Aryan Kaganof collection. Documentation Centre for Music (DOMUS), Stellenbosch University.

Kahn, D. 2001. Noise, Water, Meat: A History of Sound in the Arts. Cambridge, Mass: The MIT Press.

Kelly, C. (Ed.) 2011. Sound: Documents of Contemporary Art. London, Cambridge, Mass: Whitechapel Gallery and The MIT Press.

Ketelaar, E. 2001. Tacit Narratives: The Meanings of Archives. In Archival Science 1: 131-41.

Kipnis, L. 1989. Feminism: The Political Conscience of Postmodernism?. In Social Text No. 21: 149-166. Available: [2020, July 20].

Knabb, K. 2006. (Ed. and trans.) Situationist International Anthology. Berkeley: Bureau of Public Secrets.

Krauss, R. 2000. A Voyage on The North Sea: Art in the Age of the Post-medium Condition. New York: Thames & Hudson.

Kristeva, J. 1982. Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection. (Trans.) Roudiez, L.S. New York: Columbia University Press.

Kristeva, J. 1997. New Maladies of the Soul. In (ed.) K. Oliver, The Portable Kristeva, New York: Columbia University Press.

Kruth, P. & Stobart, H. (eds.). 2000. Sound. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

LaBelle, B. 2007. Background Noise: Perspectives on Sound Art. New York, London: Continuum.

Lake Placid-North Elba Historical Society. 2012. Home Economics History. On lakeplacidhistory.com [Online]. Available: [2020, September 13].

Laing, R. D. 1965. The Divided Self: An Existential Study in Sanity and Madness. London: Penguin Books.

Laing, R.D. 1967. The Politics of Experience. New York: Ballantine Books.

Licht, A. 2007. Sound Art: Beyond Music, Between Categories. New York: Rizzoli International Publications.

L’Internationale Online: Aikens, N., Çaka, B., Franssen, D., Haq, N., López, S., Paynter, N., Petrešin-Bachelez, N., Pinteño, A. Prieto del Campo, C., Thije, S., & Železnik, A. (editorial board). 2015. Decolonising Museums. [Online]. Available: [2016, April 7].

L’Internationale Online (editorial board) and Ištok, R (eds.). 2016. Decolonising Archives. [Online]. Available: [2016, April 7].

Lispector, C. 1977. Interview: Clarice Lispector. TV2 Cultura in São Paulo [Video file]. Available: [2019, September 11].

Lispector, C. 1992. The Egg and the Chicken. In The Foreign Legion: Stories and Chronicles. (Trans.) Giovanni Pontiero. New York: New Directions.

Lispector, C. 2012. Água Viva. (Trans.) Stefan Tobler. New York: New Directions Publishing Corporation.

Lynch, M. 1999. Archives in Formation: Privileged Spaces, Popular Archives and Paper Trails. History of the Human Sciences, Vol. 12 (2): 65-87.

Lyotard, J. 1974. Economie Libidinale. Paris: Les Editions de Minuit.

Lyotard, J. 1991. The Inhuman: Reflections on Time. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Lyotard, J. 1993. Libidinal Economy. (Trans.) Grant, I.H. Bloomington & Indianapolis: Indiana University Press.

Lyotard, J. 2004. Libidinal Economy. (Trans.) Grant, I. H. London, New York: Continuum.

Marder, M. 2014. The Philosopher’s Plant: An Intellectual Herbarium. New York: Columbia University Press.

MacKenny, V. 2002. Angry letters on “lewd” art performance give rise to NSA Forum. In ArtThrob News, No. 61 (September). Available: [2020, March 4].

Mainly Norfolk: English Folk and Other Good Music. ‘Blue Bleezin’ Blind Drunk/Mickey’s Warning’. Available: [2020, August 14].

Mbembe, A. 2002. The power of the archive and its limits. In (eds.) Hamilton, C., Harris, V., Taylor, J., Pickover, M., Reid, G. & Saleh, R., Refiguring the Archive. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic, pp 19-28.

Mbembe, A. 2015. Decolonising Knowledge and the Question of the Archive. [Online] Available: [2016, February 25].

Merewether, C. (Ed.). 2006. The Archive. London & Cambridge, MA: Whitechapel.

Merriam-Webster. S.v. ‘counterpoint’ [Online]. In Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Available: [2020, September 28].

Merriam-Webster Dictionary. S.v. ‘decentering’ [Online]. Available: [2020, October 8].

Mignolo, W. & Tlostanova, M. 2006. Theorizing from the Borders: Shifting to Geo- and Body-Politics of Knowledge. In European Journal of Social Theory, 9 (2): 205—21.

Mignolo, W. D. 2007. Delinking, Cultural Studies, 21: 2, 449 – 514.

Mignolo, W.D. 2009. Epistemic Disobedience, Independent Thought and De-Colonial Freedom. In Theory, Culture & Society, Vol. 26 (7-8): 1-23.

Mignolo, W. D. 2011. The Darker Side of Western Modernity: Global Futures, Decolonial Options. Durham: Duke UP.

Mignolo, W. D. and Vázquez, R. 2013. Decolonial AestheSis: Colonial Wounds/Decolonial Healings. In Social Text/Periscope [Online]. Available: [2016, May 23].

Mignolo, W.D. 2017. Interview: Walter Mignolo. Part 2: Key Concepts (by A. Hoffmann). In E-International Relations. Available: [2020, August 10].

Miller, S. 2015. In Defense of Medea: a feminist reading of the so-called villain. In Daily Review. [2020, March 21].

Millodot: Dictionary of Optometry and Visual Science (7th ed). 2009. S.v. ‘masking’. In thefreedictionary.com. Butterworth-Heinemann. Available: [2020, September 29].

Minh-ha, T.T. 1989. Woman, Native, Other: Writing Postcoloniality and Feminism. Bloomington & Indianapolis: Indiana University Press.

Minh-ha, T.T. 1992. Framer Framed. New York & London: Routledge.

Minh-ha, T.T. 1998. Interview: Trinh T. Minh-ha. Shifting the Borders of the Other: An Interview with Trinh T. Minh-ha (by M. Grzinic). In Telepolis [Online]. Available: [2020, October 7].

Mogorosi, T. 2018. Facebook page. 8 September. Available: [2020, September 11].

Moland, L. 2017. Friedrich Schiller. In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.). Available: [2020, June 2].

Morley, S. 2017. In praise of vagueness: re-visioning the relationship between theory and practice in the teaching of Fine Art from a cross-cultural perspective. In Journal of Visual Art Practice. Available: [2017, March 22].

Moten, F. 2018. Stolen Life. Durham & London: Duke University Press.

Müller, D. [n.d.]. ‘The Techniquer’ (1916) [Photographs]. David Müller collection, Documentation Centre for Music (DOMUS), Stellenbosch University.

Nechvatal, J. 2011. Immersion into Noise. Michigan: Open Humanities Press.

Newcater, G. [n.d.]. Assyrian Ziggurat [Pen on paper]. Graham Newcater collection. Documentation Centre for Music (DOMUS), Stellenbosch University.

Nicholson, C. 2021. Delia Derbyshire: The Myths and the Legendary Tapes review – playful paean to a musical pioneer, The Guardian, 16 May 2021. Available: [2021, June 15].

Odin, J.K. 1997. The Edge of Difference: Negotiations Between the Hypertextual and the Postcolonial. In Modern Fiction Studies 43.3: 598-630. Available: [2020, August 16].

Oliveros, P. 1999. Quantum Listening: From Practice to Theory (To Practice Practice). Available: [2021, January 9].

Oliveros, P. 2000. Quantum Listening: From Practice to Theory to Practice Practice. In MusicWorks #75, Fall 2000 Plenum Address for Humanities in the New Millennium, Chinese University, Hong Kong, 2000, Print.

Olson, S. 2011. A Grand Unified Theory of Music: Chords don’t just have sound—they have shape. In Princeton Alumni Weekly (February 9). Available: [2017, December 15].

Oosterling, H. 1989. Oedipus and the Dogon: Myth of Modernity Interrogated. In (ed.) Kimmerle, H. I, We and Body. Amsterdam.

Orlow, U. 2006. Latent Archives, Roving Lens. In (eds.) Connarty, J. & Lanyon, J. Ghosting: The Role of the Archive within Contemporary Artists’ Film and Video. Bristol, UK: Picture This Moving Image.

Pessoa, F. 1931. Autopsychography. In (Trans.) Edouard Roditi, Poetry, Vol. 87, no.1, October 1955. (Online). Poetry Foundation. Available: [2020, April 12].

Piepenbring, D. 2014. It Changes Nothing. In The Paris Review (Online). Available: [2019, September 11].

Plath, S. 2015. Collected Poems. London: Faber & Faber.

Poe, E. A. 1844. The Purloined Letter. In The Gift for 1845. Philadelphia: Carey & Hart.

Quijano, A. 2007. Coloniality and Modernity/Rationality. In Cultural Studies 21(2-3): 168-78.

Random House Unabridged Dictionary. 2020. S.v. ‘möbius strip’ [Online]. dictionary.com. Available: [2019, October 10].

Random House Unabridged Dictionary. 2020. S.v. ‘pentimento’ [Online: dictionary.com]. Available: [2020, October 8].

Rea, N. 2019. Marisa Merz, the Legendary Italian Artist Who Brought a Woman’s Perspective to Arte Povera, Has Died. In artnet News [Online]. Available: [2020, September 3].

Reckitt, H. 2013. Forgotten Relations: Feminist Artists and Relational Aesthetics. In (eds.) Dimitrakaki, A. & Perry, L. Politics in a Glass Case: Feminism, Exhibition Cultures and Curatorial Transgressions. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press.

Rhys, J. 1968. Wide Sargasso Sea. London: Penguin Books.

Rhys, J. 2001. Wide Sargasso Sea. London: Penguin Student Editions.

Rhys, J. 2012. The Voice of Jean Rhys. [Online audio: YouTube]. Available: [2020, October 8].

Ricciardi, N. 2012. Symposium: Memories Can’t Wait (2012), International Center of Photography, New York. [Online].

Rich, A. 1979. On Lies, Secrets and Silence. New York: W.W. Norton & Company.

Robertson, R. 2011. Eisenstein on the Audiovisual: The Montage of Music, Image and Sound in Cinema. London, New York: I.B. Tauris & Co Ltd.

Rosen, R.D. & Manna, B. 2020. S.v. ‘wound dehiscence’ [Online]. In National Center for Biotechnology Information. Available: [2020, September 13].

Rosenthal, M. 2003. Understanding Installation Art: From Duchamp to Holzer. Munich, Berlin, London, New York: Prestel.

Rosler, M. 1975. Semiotics of the Kitchen. [Online]. Video Data Bank. Available: [2019, November 15].

Saleh-Hanna, V. 2015. Black Feminist Hauntology. In Champ Pénal/Penal Field, Vol. XII Available: [2020, July 14].

Salvio, P. M. 2001. Loss, Memory, and the Work of Learning: Lessons from the Teaching Life of Anne Sexton. In (eds.) D. Holdstein & D. Bleich. Personal Effects: The Social Character of Scholarly Writing. Pp. 93-117. University Press of Colorado; Utah State University Press.

Salvio, P. M. 2007. Anne Sexton: Teacher of Weird Abundance. Albany: SUNY Press.

Schaeffer, P. 1966. Traité des objets musicaux. Paris: Le Seuil.

Schaeffer, P. 2017. Treatise on Musical Objects: An Essay Across Disciplines. (Trans.) North, C. & Dack, J. California: University of California Press.

Schiller, F. 1967. On the Aesthetic Education of Man. (Ed. & trans.) E.M. Wilkinson & L.A. Willoughby. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Schiller, F. 1993. Letters on the Aesthetic Education of Man. In Essays, (Eds.) D. O. Dahlstrom & W. Hinderer Essays, (Trans.) E.M. Wilkinson & L.A. Willoughby. New York: Continuum.

Schwarzkogler, R. 1965-69. Selected Scores for Unperformed Aktions. [Online] In Supervert: Electronic Library. Available: [2020, October 8].

Scrivener, S. 2002. The Art Object Does Not Embody a Form of Knowledge. In Working Papers in Art and Design Vol. 2. Available: [2020, July 19].

Sellers, S. & O’Hara, D. (eds.). 2012. Extreme Metaphors: Interviews with J.G. Ballard 1967-2008. United Kingdom: Fourth Estate.

Sheikh, S. 2009. Objects of Study or Commodification of Knowledge? In Art & Research: A Journal of Ideas, Contexts and Methods, 2(2), Spring. Available: [2017, June 2].

Smith, L.T. 1999. Decolonising Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples. London, New York: Zed Books Ltd and Dunedin: University of Otago Press.

South African Vinyl collection. Documentation Centre for Music (DOMUS), Stellenbosch University

Spieker, S. 2008. The Big Archive: Art from Bureaucracy. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Mit Press.

Spivak, G. C. 2012. An Aesthetic Education in the Era of Globalization. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Stafford, B. 1999. Visual Analogy: Consciousness as the Art of Connecting. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Stedman’s Medical Dictionary. 1995. S.v. ‘invaginated’ [Online]. On Dictionary.com. Houghton Mifflin Company. Available: [2019, November, 30].

Stewart, S. 2000. ‘Blue Bleezing Blind Drunk’, From the Heart of the Tradition, Album, Topic Records, UK. Available: [2019, January 15].

Steyerl, H. & Berardi, F. 2012. The Wretched of the Screen. New York & Berlin: Sternberg Press.

Stoll, T. 2019. Nietzsche and Schiller on Aesthetic Semblance. In The Monist, Vol. 102: 3, pp. 331-48. Available: [2020, June 2].

Sutton, J. 1998. Philosophy and Memory Traces. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

The American Heritage Medical Dictionary. 2004. S.v. ‘masking’ [Online]. In thefreedictionary.com. Houghton Mifflin Company. Available: [2020, September 29].

Thompson, L. 2013. ‘Blue Bleezin’ Blind Drunk’, Won’t be Long Now, Album, Topic Records, UK. Available: [2020, August 16].

Ukeles, M.L. 1969. Manifesto for Maintenance Art 1969!: ‘Care’ A Proposal for an Exhibition. [Online]. Available: [2020, October 9].

UKEssays. November 2018. Feminism in the works of Medea. [Online]. Available: [2020, March 21].

van Alphen, E. 2008. Archival obsessions and obsessive archives. In (eds.) Holly, M.A. & Smith, M. What is Research in the Visual Arts? Obsession, Archive, Encounter. Williamstown, Massachusetts: Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute.

van Dijk, N., Ergenzinger, K., Kassung, C. & Schwesinger, S. 2017. Navigating Noise. Kunstwissenschaftliche Bibliothek Series, Vol 54. Berlin: Buchhandlung Walther König.

van Zyl Smit, B. 1992. Medea and Apartheid. In Akroterion Journal for the Classics in South Africa, Vol. 37, No. 2, pp. 73-81. [Online]. Available: [2020, March 31].

van Zyl Smit, B. 2002. Medea the Feminist. In Acta Classica, Vol. 45, pp. 101-22. Online: Classical Association of South Africa. Available: [2020, March 21].

Vázquez, R. 2019. Decolonial Aesthesis and the Museum: An Interview with Rolando Vázquez Melken By Rosa Wevers. In (‘Towards a Museum of Mutuality’) Stedelijk Studies Issue #8 (Spring). [Online]. Available: [2021, June 15].

Verwoert, J. 2007. Living with Ghosts: From Appropriation to Invocation in Contemporary Art. In Art & Research: A Journal of Ideas, Contexts and Methods, 1(2), Summer. Available: [2017, May 5].

Visser, A.G. 1925. Lotos-Land. In Poems. Pretoria: Van Schaik.

Wallace, D. 2018. Fred Moten’s Radical Critique of the Present. In The New Yorker. Available: [2020, May 17].

Wa Thiong’o, N. 1986. Decolonising the Mind: the Politics of Language in African Literature. Harare: Zimbabwe Publishing House.

Wittgenstein, L. 1980. Culture and Value. G.H. von Wright (ed.), P. Winch (trans.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Woodward, A. 2020. Jean-Francois Lyotard. Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy: A Peer-Reviewed Academic Resource. Available: [2017, October 16].

Woolfe, V. 1929. A Room of One’s Own. England: Hogarth Press and United States: Harcourt Brace & Co.

Yuan, Y. & Hickman, R. 2016. Autopsychography as a Form of Self-Narrative Inquiry. In Journal of Humanistic Psychology. Available: [2020, April 7].

Dire Straits. 1985. ‘Money for Nothing’. Brothers in Arms. [Album]. UK: Vertigo & US: Warner Bros.

Donnelly, A. & Morse, D. 1950. ‘I Tore Up Your Picture When You Said Goodbye (But I Put It Together Again)’. Frank Petty Trio. [Vinyl, 7″]. USA: MGM Records.

Endler, R. 2011. Cello improvisations. [Studio recording]. Stellenbosch University, South Africa.

Eoan Group Opera. 1964. ‘Ah, fors’ é lui… Sempre libera’. Aria from La Traviata. [Digitised reel-to-reel tape]. South Africa.

Gurevich, M. 2014. ‘Woman is still a woman’. Let’s Part in Style. [CD]. Berlin: Michelle Gurevich & Van Roland.

Kaganof, A. 2010. ‘Anahat’. The Bow Project [CD]. Faroë Islands: TUTL Records.

Ngqawana, Z. 2005. Live interactive improvisation at Unyazi Electronic Music Symposium & Festival. [Live performance]. Zim Ngqawana. 2 September 2005, Wits University, Johannesburg, South Africa.

ORPHX. 2010. ‘Stillpoint’. Black Light. [Vinyl, EP, 12”]. USA: Sonic Groove.

Stewart, S. 2000. ‘Blue Bleezing Blind Drunk’, From the Heart of the Tradition. [CD]. UK: Topic Records.

The Song Swappers and Pete Seeger 1955. ‘Bayeza – Invocation’. Bantu Choral Folk Songs. [Vinyl, LP, 10″]. South Africa: Folkways Records.

Thompson, L. 2013. ‘Blue Bleezin’ Blind Drunk’, Won’t be Long Now. [CD]. UK: Topic Records.

Verwoerd, H.F. 1966. ‘Toespraak Deur Die Eerste Minister, Dr. H.F. Verwoerd By Die Voortrekkermonument, Pretoria. 31 Mei 1966 [Part 1]’. Dr. H.F. Verwoerd. [Vinyl LP]. South Africa: Brigadiers.

Virgins 2002. ‘Boeremuzak’. Boeremuzak. [CD]. Cape Town, South Africa: African Noise Foundation.

Wende, H. & His Orchestra. 1960. ‘Princess Waltz (Agnes Waltz)’. Africana: Africa in Rhythm. [Vinyl, EP, 7″]. South Africa: Polydor.

Xenakis, I. 1987. ‘Metaux’ Movement. DeciBells, Les Percussions de Strasbourg & Iannis Xenakis. Pléïades. [CD]. France: Harmonia Mundi.

Zimmer, N. & Webb, J. 2001. ‘Post’. Conference. [CD]. South Africa: Upland Music.

27 Sounds Manufactured in a Kitchen 1983, Available: (2020, May 24).

Blood of the Beasts 1949, Film, (Dir.) Georges Franju, (Prod.) Paul Legos, France.

Brief Encounter 1945. Online: YouTube, (Dir.) David Lean. (Script) Noël Coward, Cineguild Production. United Kingdom. Available: (2020, April 6).

Critique of Separation 1961, 35mm, B & W, 20:00, (Dir.) Guy Debord, (Prod.) Dansk-Fransk Experimenalfilms Kompagni (Copenhagen), France. Available: (2020, April 15).

Elisabeth stitching 2020, HDV, (Dir.) Nicola Deane, African Noise Foundation, South Africa.

Eyes Without a Face 1960, DVD, (Dir.) Georges Franju. (Prod.) Jules Borkon. Champs-Élysées Productions (Paris) & Lux Film (Rome). France, Italy.

How to Shop 1993, Video, (dir.) Bobby Baker & Polona Baloh Brown. From Daily Life (1991-2001): a quintet of site-specific shows. Available: (2019, November 9).

Kitchen Show 1991, Video, (dir.) Bobby Baker & Polona Baloh Brown. From Daily Life (1991-2001): a quintet of site-specific shows. Available: (2019, November 9).

Medea 1969, Film, (dir.) Pier Paolo Pasolini, Italy, France, West Germany.

Medea, falling… a poor image reconstruction 2018, HDV, (dir.) N. Deane, African Noise Foundation, South Africa.

On the Passage of a Few Ants Through a Rather Brief Unity of Time 2018, HDV, (Dir.) Nicola Deane, African Noise Foundation, South Africa.

Primal Scene 2002. DV, (Dir.) Kaganof & Deane, African Noise Foundation, South Africa.

Say it with Flowers 2017, HDV, (Dir.) Aryan Kaganof. Africa Open Institute, South Africa.

Secret Writing Techniques: Container Egg for secret messages (1579) 2015, Video, (Dir.) Jana Dambrogio & Dr Nadine Akkerman, (Prod.) MIT Video Production, Massachusetts. Available: [2020, December 5].

Semiotics of the Kitchen 1975, Video, black & white, (dir.) Martha Rosler. Available: (2019, November 11).

Signal to Noise 1997, Super 8mm, (dir.) Aryan Kaganof (prod.) F. Scheffer, Netherlands.

Something Wild 1961, Film, (dir.) Jack Garfein, Prometheus Enterprises Inc., United States.

Sur le passage de quelques personnes à traverse une assez courte unité de temps 1959, 35mm B & W, 20:00, (Dir.) Guy Debord, (Prod.) Dansk-Fransk Experimenalfilms Kompagni (Copenhagen), France. Available: (2019, November 17).

“Through the ear, we shall enter the invisibility of things” 2017, HDV, (Dir.) Nicola Deane, African Noise Foundation, South Africa.

Venus Emerging 2004, HDV, (dir.) Aryan Kaganof (Remix collection), African Noise Foundation, South Africa.

| 1. | ↑ | “This contemporary topology is composed of cracks, in-between spaces, or gaps that do not fracture reality into this or that, but instead provide multiple points of articulation with a potential for incorporating contradictions and ambiguities. Also, the in-between spaces themselves become the object of discourse as well as artistic representation” (Odin, 1997: online). |