NICOLA DEANE

PASSAGE III: NOISE A Hauntological Reconstruction of the DOMUS Archive: the noise remains

§1 Immersion into Noise

So art as white-noise-light speaks to us both at the center and at the edges of our frame of cognition (that frame semi-forced on us by the social and psychological conditioning of empiricist/positivist philosophy). And, as such, white noise art might allow us to feel the outer limits and finer levels of our most exquisite vacuole sensibilities. Because we will never succeed completely in understanding these feelings, white noise art is tragic. Because we never stop trying, white noise art is comic.

Joseph Nechvatal, Immersion Into Noise (2011: 31)

White Noise in Eight Amplified Movements (for Clarice Lispector)[1]Transcription of text for voice in my Sonic Poem: White Noise in Eight Amplified Movements (for Clarice Lispector) (2017). A collaboration with African Noise Foundation that is based on the short story “The Egg and the Chicken” (Lispector, 1964). Featured in the interdisciplinary publication “Navigating Noise” (2017: 96-106).

Movement I

I immediately perceive that I cannot be simply hearing a noise.

Hearing a noise is always in the past: No sooner do I hear the noise than I have heard a noise.

The very instant a noise is heard, it becomes the memory of a noise.

The only person to hear a noise is someone who has heard it before.

Upon hearing the noise, it is already too late: a noise heard is a noise lost.

To hear the noise is the promise of being able to hear the noise again one day.

Does thought intervene? No, there is no thought: there is only the noise.

Hearing is the essential faculty and, once used, I shall cast it aside.

I shall remain without the noise.

The noise has no itself. Individually, it does not exist.

It is impossible actually to hear the noise.

No one is capable of hearing the noise. Only machines can hear the noise.

Nor can anyone feel love for the noise.

My love for the noise is suprasensitive and I have no way of knowing that I feel this love.

One is unaware of loving the noise.

In ancient times I was the depository of the noise and I walked on tiptoe in order not to disturb the noise’s uncanny silence.

When I died, they carefully removed the noise inside me: it was still alive.

Just as we ignore the world because it is obvious, so we fail to hear the noise because it, too, is so obvious.

Does the noise no longer exist? It exists at this moment.

Noise, you are perfect. You are white.

To you I dedicate this beginning.

To you I dedicate this first movement.

§2 Navigating Noise

The sound installation by artist Kerstin Ergenzinger and physicist Thomas Laepple titled Navigating Noise[2]“Navigating Noise is a poetic exploration of the means of orientation in space through sound and movement. The installation is a site-specific, interactive sonic architecture through which visitors move freely, navigating its sounds and noises. This leads to subtle shifts in the perception of space.” (Ergenzinger, 2020: online). was the departure point for the interdisciplinary research project Acts of Orientation (directed by Ergenzinger, Laepple and Nathanja van Dijk), and provided “a shared sensorial dispositive between participants and the public” (Ergenzinger, 2020: online). Their research within the “Acts of Orientation” event investigates “how to orientate oneself at the borderline of noise” and also questions, “the notion of rhythm as a middle force between regularity and chaos as the role of gaps and lines in orientation processes such as sensing, recording, reconstructing, translating and interpreting” (Ergenzinger, 2020: online). Their efforts to present a diverse range of artistic and academic explorations of noise “as a theoretical and philosophical concept, and noise as a physical and sonic phenomenon, both within and beyond the boundaries of sound,” resulted in the publication of “Navigating Noise” (2017: 28). The installation provided the framework for the publication of varied contributions that “address the need for alternative means of orientation to deal with noise and to understand and (re)establish our unstable position within a highly technologized, mediated, and globalized reality” (2017: 28). The aim and value of their research process is measured by Ergenzinger in the following way:

Investigating such navigational systems or situations from the perspective of noise, i.e. what is excluded, dangerous, or unprocessable, one can unveil a system’s foundations and internal logics. In this way, a fresh perspective for critical evaluation is offered. Instead of macro-politics it is the micro-political which forms every act of orientation (Ergenzinger, 2020: online).

My artistic contribution to the publication of this research project was in text form (pp. 96-106), and was “performed” as a sonic poem at the public event “Acts of Orientation” in the series Salon für Ästhetische Experimente at the Haus der Kulturen der Welt, Berlin, on 12 February 2018. My sonic poem White Noise in Eight Amplified Movements (for Clarice Lispector) provides a bridge from passage II since it is based on the same text that narrated my short film “Through the ear, we shall enter the invisibility of things” and the bridge continues to my next audiovisual study Medea, falling… a poor image reconstruction (2017)

Movement II

The noise is something in suspense. It has never settled.

When it comes to rest, it is not the noise that has come to rest.

A surface has formed beneath the noise.

I vaguely glance at the surface noise in the kitchen in order not to break it.

I take the greatest care not to understand it.

It cannot be understood and I know that if I were to understand the noise, it could only be in error.

To understand is a proof of error.

Never to think about the noise is one way of having heard it.

Could it be that I know about the noise?

What I do not know about the noise is what really matters.

What I do not know about the noise gives me the noise itself.

§3 amplified cryptonymic ruins

a short film script by Nicola Deane

Medea, falling… provides a sketched thought trajectory from mythologies to cryptonymies[3]Referring to The Wolf Man’s Magic Word: A cryptonymy (Abraham & Torok: 2005) and their theory of the crypt as “the burial of an inadmissible experience” (International Dictionary of Psychoanalysis, 2020). to hauntologies[4]A portmanteau of haunting and ontology; Derrida’s term from Spectres of Marx: The State of the Debt, the Work of Mourning and the New International (1994). in terms of the possible engagements with historical records and the field of collective memories and secrets. In his article “Hauntology, Spectres and Phantoms” (2005), Colin Davis detects in what he calls “the status of the secret”, “[t]he crucial difference between the two strands of hauntology, deriving from Abraham and Torok and from Derrida respectively” (2005: 378). He notes that the secrets of Abraham’s and Torok’s lying phantoms[5]“What they call a phantom is the presence of a dead ancestor in the living Ego, still intent on preventing its traumatic and usually shameful secrets from coming to light” (Davis, 2005: 374). are only unspeakable as subjects of “shame and prohibition”, but once put into words “may be exorcized” (Davis, 2005: 378). Whereas the psychoanalysts Abraham & Torok ultimately “seek to return the ghost to the order of knowledge”, the philosopher Derrida “wants to avoid any such restoration and to encounter what is strange, unheard, other, about the ghost… [whose] secret is not a puzzle to be solved; it is the structural openness or address directed towards the living by the voices of the past or the not yet formulated possibilities of the future” (Davis, 2005: 379). Davis observes that the difference between lying phantoms and gestural spectres “poses in a new form the tension between the desire to understand and the openness to what exceeds knowledge” (2005: 379). Davis claims that since Derrida’s ghost “pushes at the boundaries of language and thought”, the interest is not in secrets “understood as puzzles to be resolved, but in secrecy now elevated to what Castricano calls “the structural enigma which inaugurates the scene of writing” (Cryptomimesis: 30)” (Davis, 2005: 379). Davis concludes that in the context of literary studies, the endeavor of hauntology is to “interrogate our relation to the dead, examine the elusive identities of the living, and explore the boundaries between the thought and the unthought” (2005: 379).

Movement III

The noise exposes everything.

Anyone who fathoms the noise, who can penetrate the noise’s surface, is seeking something else: that person is suffering from hunger.

For the noise is a noise in space.

A white noise against a blue background.

Noise. I love you. I love you like something that does not even know it loves another thing.

I do not hear it. It is the aura of my ears that hears the noise.

I do not hear it. Can the noise hear me? Is it trying to fathom me?

No, the noise only hears me.

And it is immune to that painful understanding.

The noise has never struggled to be a noise.

The noise is a gift. It is inaudible to the naked ear.

A noise needs careful handling.

This is what a mother is for.

The noise lives like a fugitive because it is always ahead of its time: it is more than contemporary: it belongs to the future.

It lives inside the body so that no one may call it white.

The noise is really white but must not be called white.

Not because this would harm the noise which is immune from danger, but those people who state the obvious by describing the noise as white renege on life.

§4 nothing outside the frame…

I came to the poor image late via Derrida’s parergon then on to the frame falling… The punched in poor image frame frustrates and fragments expectations. It avoids the centre and dissolves the edges of the view, from the perspective of the viewer, creating an immersive subjective experience that feels somehow incomplete. The poor image fractures the (unreal) establishing shot/total frame composition that comes from an art of judgement (after Kant) – that is a representation of reality – but experience does not come in a total shot. With the deterioration of the image the fractured frames are actually made cohesive again, almost painterly, through the experience of work… subject/object merge, stutter, fracture, feel through one another.

Movement IV

A noise is the most naked thing in existence.

Regarding the noise, there is always the danger that we may discover what could be termed beauty, in other words, its utter veracity.

The noise’s veracity has no semblance of truth.

Our advantage is that the noise is inaudible to the vast majority of people.

And so the noise puts us at risk.

She does not know that the noise truly exists.

Were she to know she has a noise inside her, would she be saved?

She only exists on behalf of the noise.

She suffers from some strange malaise.

Her strange malaise is the noise.

The slightest threat of danger and she screeches her head off.

All this simply to ensure that the noise does not break inside her.

The noise which breaks inside her has the appearance of blood.

She watches the horizon.

§5 … a poor image reconstruction

The “poor image strategy” that I apply to my audiovisual study, Medea, falling… , has its foundation in Hito Steyerl’s famous essay “In Defense of the Poor Image” (in Steyerl, 2012), that I cannot introduce more succinctly than she does, regarding the digital territory of images in ruin:

The poor image is a copy in motion. Its quality is bad, its resolution substandard. As it accelerates, it deteriorates. It is a ghost of an image, a preview, a thumbnail, an errant idea, an itinerant image distributed for free, squeezed through the slow digital connections, compressed, reproduced, ripped, remixed, as well as copied and pasted into other channels of distribution (Steyerl, 2012: 32).

I use the poor image as a subversive strategy to corrupt the categories and diffuse the frame, as the image threatens to dissolve into surface noise. What I mean by a poor image reconstruction, is an edit that seeks the peripheral points of view of any given sequence of images, unhindered by the rules of “good/rich” cinematography regarding such things as establishing shot, focal point of composition, and being in focus. It also repudiates the digital aspirations of image detail and sharpness via high-resolution quality standards.

§6 the bonds of imperfection

In her impassioned defense of poor images, Steyerl discusses their value and conditions of existence as “the contemporary Wretched of the Screen”. She builds this discussion within the political, cultural and ideological domain in terms of Resolution, Resurrection, Privatisation & Piracy, Imperfect Cinema, and Visual Bonds. For the latter two she draws on Cuban Film director Juan García Espinosa’s manifesto: For an Imperfect Cinema (1969) and what Soviet film director and theorist Dziga Vertov termed “visual bonds”, in order to reflect on the status and potential of the poor image as an alternative economy of images today (Steyerl, 2012: 42). In his manifesto Espinosa calls for radical resistance to the “perfect cinema” of the West, and declares the new ideal for Latin American Film practices to be an imperfect cinema that is “no longer interested in quality or technique… no longer interested in predetermined taste, and much less in ‘good taste’” (Espinosa, 1969: online). On the last point he remarks further: “Taste as defined by high culture, once it is ‘overdone’, is normally passed on to the rest of society as leftovers to be devoured and ruminated over by those who were not invited to the feast” (Espinosa, 1969: online). He goes on to discuss artistic criteria for engaging the audience’s issues of the day, thereby fueling audience participation and agency to create “not merely more active spectators, but genuine co-authors” (Espinosa, 1969: online).

Steyerl argues that the marginal economy of poor images and its “ethics of remix and appropriation” points to a contemporary version of imperfect cinema, and in some way reflects Espinosa’s ideal projection of a democratisation of art/cinema practices for, by, and of the people, with the proper integration of art with life and science: “Art will not disappear into nothingness; it will disappear into everything” (Espinosa, 1969: online).

Today, with the technological evolution of new media and the ease of access, participation and distribution circuits of the Internet, the distance or distinction between producer/author and consumer/audience begins to collapse, and the poor image is freed by its abject status in the class system of market-driven images, granting Espinosa’s wish for “the truly revolutionary position… overcoming these elitist concepts and practices” (Espinosa, 1969: online).

Steyerl points out that rare film and video works from the past, including activist, avant-garde and classic art cinema forms, have been made publicly available online (via UbuWeb or YouTube) as poor image reproductions – resurrected from the archive/cave of noncommercial, nonconformist and marginalised visual material (2012: 35-8). Steyerl suggests that the exile of these works to the margins is a consequence of the neoliberal policies that restructured media production according to budget prohibitions as well as the “neoliberal radicalization of the concept of culture as commodity” (2012: 35-6). Steyerl believes that the revival of these rare cultural artifacts of cinema and video art, although degraded and downgraded to poor image format via online streaming and sharing, has led to broader audience engagement across time, in terms of their circulation and appropriation, “users become the editors, critics, translators, and (co)-authors of poor images” (Steyerl, 2012: 40).

Steyerl envisions the liberated poor image being “propelled onto new and ephemeral screens stitched together by the desires of dispersed spectators” (2012: 43). She compares this “stitching” that the circulation of poor images generates to that of “visual bonds” – a term borrowed from Dziga Vertov – by which he envisioned a common visual language through film that would connect the scattered workers of the world to each other, united by sight and recognition of one another represented as parts of the whole, thereby forging mutual ideals and a sense of solidarity. Applying that parallel to the digital network, online file sharing, comment posting and liking exposes the common global desires to recognize and relate to one another despite geographical or cultural distance, and to create mutual exchanges and acknowledgements within the readily available information market. Steyerl notes that the “optical connections” sprung from cellphone and PC-based poor image circulation,

reveal erratic and coincidental links between producers everywhere, which simultaneously constitute dispersed audiences. The circulation of poor images feeds into both capitalist media assembly lines and alternative audiovisual economies (Steyerl, 2012: 43).

Steyerl discusses the poor image circuit and its impact on generating “an imperfect cinema existing inside as well as beyond and under commercial media streams” by means of file sharing. Even the most obscure or marginalized content may be disseminated, casting its net across a globally dispersed audience, establishing a growing shared history and new platforms for public debate. In this way, Steyerl suggests that the poor image acquires a new kind of aura that is “no longer based on the permanence of ‘the original,’ but on the transience of the copy” (2012: 42).

§7 my hauntological approach to DOMUS as crypt

When considering the archive that generally houses material, analogue and digital records, the digital platform of the archive carries the most potential in terms of opening and connecting the records to other networks of information across the globe, allowing new and dynamic interactions within the constantly shifting conditions of cyberspace. Now if I am to think of hauntology as “the agency of the virtual, that which acts without (physically) existing” in Mark Fisher’s terms (2014: 31), then the digital realm seems to fit the mark. If the original record is not physically present in the digital archive but formed as a “true/genuine” (and high resolution) copy, a digital doppelgänger of the material record, then that which is not present but virtually active (as a digital representation of itself in an information network) also applies to the original, making the original a revenant as well. Digital and web networks therefore facilitate open and alternative visual and aural economies. The poor image and poor sound are thereby liberated in the digital realm – connected and connecting…

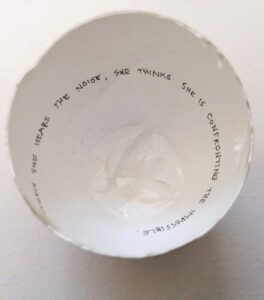

Movement V

As if she were listening to a noise slowly emerge from the distant horizon.

How can she understand herself when she is everything the noise is not?

She neither recognizes the noise when it is still inside her nor when it has been exteriorized.

When she hears the noise, she thinks she is confronting the impossible.

And suddenly I hear the noise in the kitchen and all I see there is food.

My heart is beating fast. Something is changing inside me. I can no longer hear the noise clearly.

Apart from each individual noise, apart from the noise one consumes, the noise no longer exists for me.

I can no longer bring myself to believe in a noise.

I have been listening to a noise for so long that it has hypnotized me and sent me to sleep.

I am still talking about the noise.

Only to realize that I do not understand the noise.

All I understand is a broken noise: broken in the vacuum cleaner.

And this is how I indirectly pledge myself to the noise’s existence.

§8 decentering by dissolution

My audiovisual experiment in the Noise phase of my study produced Medea, falling…a poor image reconstruction (2017).

Brief synopsis: A short film study (duration 07:23) that fabricates a hauntological approach to decentering the archive employing a poor image strategy to the edit of appropriated material (from inside and outside the archive collection). A pale young woman walks along a bridge, visibly driven by some inner distress, while we (the viewers) are sonically transported by multiple voices repeating phrases about water and falling within an oneiric electronic soundscape. She pauses to contemplate the waterscape below her since the sky offers no comfort, “I see no clouds at all…” She seems to long for something underneath the surface of the water, she is feverish and gives way to the hallucination of dying, “Suddenly I’m falling…”

§9 … off the edge of the archive

I feel as if I’m falling, or rather, that the ground is falling away from me, like those fairground spinning tunnel-of-terror machines that we submit to on occasion for cheap thrills – thrills that take us to the edge of feeling: that fleeting but utter intensity of experience and total presence in the moment, an electrified state of being. The Ancient Greeks captured those charged states of being with their plays linked to the gods. Narratives were shaped and designed to frame the psycho-emotional states of humanity, and played back to the contemporary audience. My reference to Medea in the title of this film study, is the tragic figure in Euripides’ version[6]First produced at the Great Dionysia in Athens in 431 BC. of the ancient myth that was fairly subversive for its time as the barbarian princess commits filicide. However, it has also been read more recently within a feminist frame by which Medea struggles against the patriarchal and xenophobic society of her setting to take charge of her own life.[7]For examples see “In Defence of Medea: a feminist reading of the so-called villain” (Miller, 2015), and “Feminism in the works of Medea” (UKessays, 2018). In her article, “Medea the Feminist”, Betine van Zyl Smit identifies modern adaptations of Euripides’s complex character and observes, “the most frequently explored theme is that of the subjugation and domination of women by men. It is in this last case that Medea has become a symbol for women and an icon of feminism” (2002: 102). There have been many interpretations and reinterpretations of Euripides’ Medea across the arts of film and drama. Pier Paolo Pasolini’s film Medea (1969) stars Maria Callas in her only film role, but he subverts little in his representation. A more radical remake that is closer to home is discussed in another of van Zyl Smit’s articles, “Medea and Apartheid” (1992): Demea (1990), Guy Butler’s dramatic re-contextualization by which he produced “a political allegory of the South African situation […] at the height of the idealistic Verwoerdian mania” (1992: 75). Though the play is set in the colonial Southern Africa of the late 1820s before the Great Trek (1835-1846), Butler’s transposition (or remix) of the Euripidean drama deals with the racial and cultural prejudice of the apartheid years of South Africa.

Somehow as a young woman of about twenty, I identified with Medea’s position, while studying the story via Pasolini’s film for my filler course: Ancient Greece and Rome in Film. I have since that time always kept a place for her in my poetic imagination.

§10 There is a Medea (falling) in every mother[8]The line of a poem from my personal archive that reflects the weave of the history of my practice (2008-2020).

dragging their little heads by the hair

come on down my pretty

to the edge of the mask

soon one gets used to the taste of nothing

the secret parts of my mask are still recovering

i am addicted to the poison of his noise

distasteful

while i blush to discover my limits

he forces my mask to the surface

but denies any rupture

with every wince

i relish the taste of his psalm

i get closer to knowing my mask

my fullness

§11 … the noise inside her

Medea, falling… does not form a single continuous narrative but links the three zones that are captured: the bridge and the reflective surface of the water (from the online poor image version of the 1961 film Something Wild), and an underwater scene sampled from the Kaganof video collection within DOMUS: Venus Emerging (Kaganof: 2004). The mix is rendered hauntological through its “poor image” reconstruction (Steyerl: 2012).

The soundscape is continuous across these scenes and transmits an eerie emulsion of voices: variants of British accents that echo, fuse, fracture, all referring to the state of falling, while infused with samples from the soundtrack of another film from the DOMUS collection, Signal to Noise (Kaganof, 1997); evidently non-diegetic sound, and yet proffering internal monologues that slip in and out of their visual context. The soundtrack is not directly synched to the image, the scenes are not seamlessly sutured, the shots are not conventionally scaled to be read effortlessly, and the footage shifts back and forth from black & white to muted colour – all contributing to a sense of incongruence.

The poor image tends towards abstraction: it is a visual idea in its very becoming.

Steyerl, The Wretched of the Screen (2012: 32)

The soundtrack of Medea falling… (2017), is sampled from the sonic work of Delia Derbyshire (1937-2001), an English composer of electronic music who was bound to anonymity and group identity of the BBC Radiophonic Workshop. Her experimental work remained lost in the attic in reel-to-reel tapes and personal papers till her death related to chronic alcoholism. It is primarily made up of an excerpt from The Dreams from “Inventions for Radio” in collaboration with poet and dramatist Barry Bermange, in which Derbyshire designed an electronic soundscape using recorded voices to represent sensations of “the dream condition” in five movements: running away, falling, landscape, underwater and colour. Derbyshire’s treatment of the material by which she creates ominous, haunting atmospheres is best described as “musique concrete soundbeds” (Derbyshire, 1964: online). I limited my selection to the falling movement, and used only female voices. The other components of the soundtrack include doves cooing and a Japanese drum roll from Signal to Noise (1997) in DOMUS. My quoting of Derbyshire’s work in this audiovisual sketch directly ties up with the hauntological theme of this Passage, to the annihilation of the female creator in a context of group identity: confined to the attic, to the ktichen, to the archive of the marginal.

Movement VI

And from this very moment the noise no longer exists.

Anxious to avoid destruction, we destroy ourselves.

Love is not a prize. It is a state conceded only to those who would otherwise contaminate the noise with their private sorrow.

This is the sacrifice we make so that the noise may be formed.

§12 From mythology to noise to hauntology…

I came to hauntology through the British writer and critical theorist Mark Fisher (Ghosts Of My Life: Writings on Depression, Hauntology and Lost Futures, 2014), which led my meditations on depression to include the state of falling and the state of dreaming. For my own research purposes, I place Fisher’s book alongside Hito Steyerl’s “In Defence of the Poor Image” (2012) that is mainly concerned with visual culture, whereas Fisher primarily examines music culture with an interest in surface noise[9]Noise produced by the friction of the needle or a stylus of a record player with the rotating record, caused by a static charge, dust, or irregularities on the surface of a record (Collins English Dictionary, 2014). that he identifies as the “principal sonic signature of hauntology: the use of crackle” (2014: 33). This sonic signature may be read as “poor sound” in terms of the technological advancements that have developed a keener (commercial) ear for “clean sound” that is stripped of any noise defects or sonic materialities. This correlates with the market-driven ambition of precision and perfection regarding sound recording and production (unless of course those poor/aged qualities are required for stylistic affect, for example the retro genre, where they too can be digitally simulated and “mastered”). Fisher shares Steyerl’s observation of the negative impact of neoliberalism on the demise of experimental cultural production, and the subsequent capitalist promotion of reproductions of the already successful cultural artifacts of mainstream circulation and mass distribution (2014: 28). He compares the experimental culture of the twentieth century “seized by a recombinatorial delirium… as if newness was infinitely available”, to the twenty-first century culture that is “oppressed by a crushing sense of finitude and exhaustion” (Fisher, 2014: 20), that is marked (most notably in popular music culture) by “anachronism and inertia” which has been “interred behind a superficial frenzy of ‘newness’, of perpetual movement”. Fisher notes that the mash up of time, “the montaging of earlier eras, has ceased to be worthy of comment; it is now so prevalent that it is no longer even noticed”, and he thereby perceives “a general condition: in which life continues, but time has somehow stopped” (2014: 18), by which the sense of “dyschronia, this temporal disjuncture” persists (2014: 26). Fisher goes on to refer to Franco “Bifo” Berardi’s After the Future (2011) with the statement “the slow cancellation of the future has been accompanied by a deflation of expectations” (Fisher, 2014: 20).

In his discussion of Derrida’s hauntology Fisher explains how the concept came to be connected to popular culture at the start of the twenty-first century: “it was at this moment when cyberspace enjoyed unprecedented dominion over the reception, distribution and consumption of culture – especially music culture” (2014: 33). The music critics (including Fisher) influenced by the term at that time applied it to a certain group of artists (the Ghost Box Label, The Caretaker, Burial, Mordant Music amongst others), not directly influencing one another, but bearing a mutual sonic disposition, that of melancholy. They were “preoccupied with the way in which technology materialized memory – hence a fascination with television, vinyl records, audiotape, and with the sounds of technologies breaking down” (2014: 33). Fisher distinguishes hauntological music from the postmodern anachronism or “nostalgia mode” (Fredric Jameson’s term) that he understands to be “a formal attachment to the techniques and formulas of the past, a consequence of a retreat from the modernist challenge of innovating cultural forms adequate to contemporary experience” (2014: 24). Fisher refers to Radical Atheism: Derrida and the Time of Life (2008), in which Martin Hägglund argues Derrida’s concern for the collapse of time and his aim “to formulate a general ‘hauntology’”. Hägglund continues: “What is important about the figure of the specter, then, is that it cannot be fully present: it has no being in itself but marks a relation to what is no longer or not yet” (Hägglund, 2008: 82). Fisher therefore prefers to think of hauntology in terms of temporal disjuncture and as “the agency of the virtual, that which acts without (physically) existing” (2014: 31).

§13 The image deterioration focuses the sonic

With the gradual decline or deterioration of the image plane into pixelated ruin, the agitation of the frame in Medea, falling… – from the establishing shots more faithful to the cinematic frames of the original film to the destabilising extreme close-ups (punched-in) of the poor image reconstruction – in fact makes the viewing experience of the work and the states that it infers (via audiovisual recomposition) more cohesive. Although the subject of the film/moving image is rendered fractured (different voices, different faces), the subjective experience of the viewer is given sharper focus. That is, focuses our attention to the soundtrack. This image process paradoxically liberates Medea, falling… from the domination of the optical. Suddenly you are in the realm where visual work is not hampered by semiotics – the visual field is side-stepped, the semantic field of meaning is now entirely sound-based, entirely aural. This is, paradoxically, due to the carceral effect of the poor image. The poor image incarcerates our eyes in order to liberate our ears. It is an entirely digital device – a means of decentering and getting across the borders of the senses – providing a cross pollination of previously distinct disciplines, hitherto separately archived traditions (cinema, art, sound, drama, traditional music, radio broadcast and electronic music). In this way, the decentered poor image reconstruction of the record shares conceptual resonance with both border thinking and de-linking whilst, by dint of its title, ironically re-engaging with the history of the myth, of meditations of myth, of narrative and, indeed, of the archive of names and naming, of nomenclature. Where Steyerl suggests that “[t]he image is liberated from the vaults of cinemas and archives and thrust into digital uncertainty, at the expense of its own substance” (Steyerl, 2012: 32), I would claim the same for sound, and its poor quality reconstruction as delinked sonic marker in this study.

§14 Back to the archive… and desire

What is this desperate desire?

To store and file away what amounts to daily detritus – capture, upload, share, comment, like. To present oneself within the best possible frame, calling upon the carefully edited album to rectify the record of one’s pointless existence. To connect to larger collections, to enlarge one’s own collection via harmonious juxtapositions, carefully styled/posed/tagged… collectively accessorized. To materialize time, to hold on to it in frames, that may speak to the collected cohort of friends that like and share further, capture further, a frame of networks that are constantly in flux.

Framing life. Cataloguing time. Tagging ephemera. Palimpsest(ic) time.

This desire drives, as Derrida noted, to construct its own destruction – time captured makes markers (on the cutting table – whether butcher, surgeon, or editor) for what is past, and what is possible (future potentials). One can hold onto the past through the active, symbolic/imaginary, and sensorial realms of remembering: reassembling events and their fractured accounts, reframed, retold and recycled in and for the psyche, or, by handling, scanning, reading and hearing the materialized records of time, i.e. objects, photographs, paper documents, audio recordings, and other memorabilia, or, by memorializing rituals through symbolic play and the symbolic cut. The editor has a million possibilities, or plateaux, for the story to unfold within. The film medium can create cross sections of time while creating a timeline for the present. Watching in real time, there is the temporal play within the film medium, and the temporal space of watching that constructed timeline. The here and now is fleeting. “I see” becomes “I saw” all too quickly. That “lost time” must be captured before that disintegrative quality of time catches up with me too quickly – time will devour me. The advent of recording technology and its practices has shifted such existential concerns, and allowed one to capture reels of time. Writing practices were of course the first to grapple with that evidence of time’s potential to “weather” and disintegrate experience. If the event or the experience thereof is articulated and captured (involving an editing process), it may be remembered and its resonance may be resurrected by the (future) reader. The birth of the phonograph opened the territory for the voice as carrier of the message/story/experience to be captured, shared and repeated.

Nicola Deane – voice recording détourned from Clarice Lispector’s text “The Egg and the Chicken” (1992), translated by Giovanni Pontiero. Recorded using Sennheiser microphones and mixed on Final Cut Pro 7. Includes samples from ‘Anahat’ (Remix by Aryan Kaganof of Michael Blake’s ‘String Quartet #3’) (2010). Piano improvisations by Nicola Deane, recorded using Rhode microphones.

Communication and recording technologies amplify and frame our experiences, as Steyerl puts it:

The poor image is no longer about the real thing—the originary original. Instead, it is about its own real conditions of existence: about swarm circulation, digital dispersion, fractured and flexible temporalities. It is about defiance and appropriation just as it is about conformism and exploitation. In short: it is about reality (Steyerl, 2012: 44).

Steyerl’s conclusive statement on the poor image and reality led me to question the idea of the original in terms of the analogue and digital realm of archival records. Where does the original/real lie in the digital/virtual realm? In the virtual archive, the digital record is dangerously close to the material original, in terms of visual information and resemblance, it represents the original record in the best possible light and highest possible resolution that digital technology can provide us today. It is open, accessible and capable of linking to other networks of information.

§15 The mask of the poor image

The completely fractured poor image lies behind the mask of coherent, tidy and smooth edges. Capitalism sells to you an image of self that you aspire to and buy into – that image is perfect: botox, make-up, accessories, to keep you ageless, you are constantly being renewed – the perpetual renewal machine is you continuing and consuming the image of yourself. It is self-imaging, not self-portraiture any longer. You are a replicant of the image of yourself; you are the clone/android of yourself. Symbolically rendered as the liberal humanist individuated self for an app that is constantly being upgraded, you are not an android, but an appdroid. Now, the truth is, you are not that at all, and you cannot afford to keep upgrading. Everything is a lie, everything is falling apart, falling into ruin, falling… what you really are is the poor image of yourself, but you refuse to see this and prevent yourself from seeing this by wearing the mask; not to prevent others from seeing the mask, but to prevent yourself from seeing your own poor image. The poor image is the repressed and, just like the Freudian Monstress, always returns, must return – the inevitable eternal return… – the poor image is the truth, beneath the mask of perfection, because of the mask of the capitalist image.

The body conquers the invisible territory of the soul. There is nothing you can do about it. You are overwhelmed with images. They carry you away, they replace you, you are dreaming. The spectacle is life as a dream – we all want this.

Julia Kristeva, New Maladies of the Soul (1997: 207)

I’m not making narratives from the archive. One never knows the full story or necessarily comprehends the full picture. There are always multiple views to the truth, and not all of them are recorded. One should surely not be ostracized for one’s particular point of view, since one’s position is always shifting, just as time shifts everything. One is always physically present at any one time in time. Pure presence in the moment equates being in time with time. We follow myths and narratives for meaning and closure. As Samuel Beckett has said via his character Hamm in Endgame: “The end is in the beginning and yet you go on” (1958: 12).

Movement VII

The noise sizzles in the frying pan and, lost in a dream, I prepare breakfast.

Without any sense of reality, I call the children who jump out of bed, draw up their chairs and start eating and the work of the day which has just dawned begins, with shouting and laughter and food, the white noise provokes laughter.

It makes me smile in my mystery.

They have also allowed me time so that the noise may form inside me at its leisure but I have frittered away my time in illicit pleasures and sorrows, completely forgetting about the noise.

Or is this precisely what they wanted to happen so that the noise may be formed?

For with my wandering thoughts and solemn foolishness I might impede what is happening inside me.

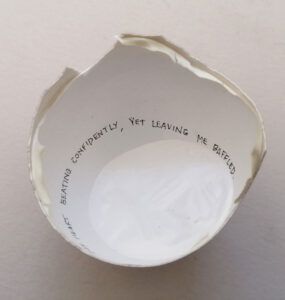

My heart beating with emotion, yet without understanding anything!

My heart beating confidently, yet leaving me baffled.

§16 Not I [10]Samuel Beckett wrote in 1972: a monologue for stage in which the sole visual on stage is the performer’s mouth.

now but the I passed, as well as the I remembered… recalled and retold by the present I – with a mind in gradual but premature ruin – the present context as mother, bound to have my Medea moment, if not now, then in the future. Which ending will I follow? I wonder… Mise en abyme… But “the abyss elicits analogy”, according to Derrida’s “Parergon” (1979: 4).

§17 Marginal samples…

In my audiovisual studies I have extracted parts of the Kaganof remix collection, which consists of remixed and re-edited video and film works from the “sample at will there is no copyright” section of the collection. These remixes (Venus Emerging & Signal to Noise) reference and appropriate other works, but I am sampling in turn from the remix, therefore quoting the remix (and “marginal”) over the original. In Living with Ghosts: From Appropriation to Invocation in Contemporary Art (2007), Jan Verwoert discusses the shift in time regarding the appropriation of “capitalist commodity culture” in the art field:

…the specific difference between the momentum of appropriation in the 1980s and today lies in the relation to the object of appropriation – from the re-use of a dead commodity fetish to the invocation of something that lives through time – and, underlying this shift, a radical transformation of the experience of the historical situation, from a feeling of a general loss of historicity to a current sense of an excessive presence of history, a shift from not enough to too much history or rather too many histories (Verwoert, 2007: 3-4).

In her Scope article “Ethical Possession: Borrowing from the Archives” (2009), Emma Cocker suggests an interpretation of the artistic use of archival footage in line with other forms of “cultural borrowing” as “a specific tactic for resisting and responding to the pressures and accelerated temporalities of late capitalism,” and considers the “dislocation (from both present and past) experienced by the individual in relation to the global and increasingly virtual context in which they are expected to perform” (2009: 92). She goes on to suggest that “what is at stake perhaps in the gesture of borrowing images from the archive is an attempt to craft an ethics for the present” (Cocker, 2009: 92). Cocker continues:

It is a practice of re-writing history in order to gain a fresh perspective on both the past and the current situation, a process of inventory and selection of what has gone before in order to provoke new critical forms of subjectivity through which to apprehend an uncertain future (Cocker, 2009: 92).

The “cultural products” that I am sifting through and appropriating – although discovered within the DOMUS archive – do not appear to have anything to do with the South African music landscape or aural-scape. The study I initiated in 2016 was how to engage with history today, and how to actively self-reflect through historical documents while keeping in mind the words of Frederick Douglass on the truth being the soul of art: “The dead fact is nothing without the living expression” (from “Pictures and Progress: An Address Delivered in Boston, Massachusetts, on 3 December 1861”).

§18 The New Archive

Wolfgang Ernst’s discussion of “Radically De-Historicising the Archive: Decolonising Archival Memory from the Supremacy of Historical Discourse” (2016), asserts in similar terms to those of Steyerl, that:

Although the traditional archival format (spatial order, classification) will in many ways necessarily persist, the new archive is radically temporalised, “ephemeral”… multi-sensual, corresponding with a dynamic user culture which is less concerned with records for eternity than with order by fluctuation (Ernst, 2016: 15-16).

Ernst identifies the technological advances in the digital domain of archiving and regards “data bank structures [of] the archival mode of memory (record management) [as] a non-narrative alternative to historiography” (2016: 12). He argues for a media-archeological (as opposed to iconological) approach to processing archival materials in order to “liberate archival memory from its reductive subjection to the discourse of history and re-install it as an agency of multiple temporal poetics in its own right” (Ernst, 2016: 11-12). Ernst uses the language and terms of computer technology and the Internet to address the debates of the archive, and reflect on its temporal status in the shift from analogue to digital, and physical to virtual domains.

§19 Poor Art to Noise Art

In Steyerl’s assessment, the poor image is situated in relation to the “historical genealogy of nonconformist information circuits”, and may be aesthetically compared to the low art materials that were used to visually support, inform and spread: “carbon-copied pamphlets, cine-train agit-prop film, underground video magazines, and other nonconformist materials” (Steyerl, 2012: 43-4). Steyerl’s view for a more radical or political potential of the poor image may also call to mind the late-1960s contemporary art movement emerging from Italy, termed Arte Povera (Poor Art) by the art critic Germano Celant. Arte Povera grouped a collection of predominantly Italian artists making art from “poor” or common materials and found objects, in reaction to (dated) abstract painting, and the high (corporate and institutional) values of art and culture of the day. In his manifesto Arte Povera: Notes for a guerilla war (1967), Celant takes a stance against the system of society that “presumes to make pre-packaged human beings, ready for consumption” that are obliged to contain their roles and creativity well within the system’s commands: “Each of his gestures has to be absolutely consistent with his behavior in the past and has to foreshadow his future. To exist from outside the system amounts to revolution” (Celant, 1967: online). Celant stresses the negative impact of such a system on the artist (who is for the most part of Arte Povera male, with the exceptional “woman’s perspective” provided by Marisa Merz):

Mass production mentality forces him to produce a single object that satisfies the market to the point of saturation… He has to follow up on it, justify it, introduce it into the channels of distribution, turning himself as artist into a substitute for an assembly line. No longer a stimulator, technician, or specialist of discovery, he becomes a cog in a mechanism. This work presupposes the rejection of any and all systems and of all codified expectations. A free mode of action, unforeseeable and without restraints and franchised to frustrate expectations, to straddle the borderline between art and life (Celant, 1967: online).

Movement VIII

But what about the noise?

As I was talking about the noise, I forgot about the noise.

“Keep on talking, keep on talking” they told me.

And the noise remains completely protected by all those words.

Out of devotion to the noise I forgot about it.

Forgetfulness born out of necessity.

For the noise is an evasion.

Confronted by my possessive veneration, the noise could withdraw never to return and I should die of sorrow.

But suppose the noise were to be forgotten and I were to make the sacrifice of getting on with my life and forgetting about it.

Suppose the noise proved to be impossible.

Then perhaps – free, delicate, without any message whatsoever for me – the noise would move through space once more and come up to the window I have always left open.

And perhaps with the first light of day the noise might descend into our apartment and move serenely into the kitchen.

Clarice Lispector détourned by Nicola Deane for African Noise Foundation, published in Navigating Noise (2017: 96-106).

§20 Back to falling…

That lightheaded feeling of falling: danger compressed and masked, and worn for entertainment’s sake: that full engagement with one’s stomach as encountered on a roller coaster ride. The stomach lifts and falls abruptly – it makes one giddy and prone to shrieking with the hysterical gesticulations that come with being in an exhilarated state. My first real leap of faith in order to gain attention involved a different kind of falling – I jumped into the deep end and began to sink as if in slow-motion I languidly observed the bubbles bursting gently before my face, before being whisked upward in much faster motion: up and out into the open to meet the post-drowning huddle, to be contained and saved by it. I was now ready to swim without aid of floaters – it had to be announced in such a way: by dramatic performance. I was hurriedly handed some candy to supposedly dispel shock and soothe me. But something deep inside me vibrated on another reading: that I was being rewarded for jumping into the deep-end and exhibiting fearlessness. This awakened me to the fact that the interpretation of any action has many more angles than is apparent in the passing moment and that awakening pivoted on the experience of a transgression.

Abraham, N. & Torok, M. 1994. The Shell and the Kernel: Renewals of Psychoanalysis, Vol. 1 (Trans.) Rand, N. Chicago & London: University of Chicago Press.

Abraham, N. & Torok, M. 2005. The Wolf Man’s Magic Word: A Cryptonymy. (Trans.) Rand, N. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Acce Pointtopoint. 2011. Not I (1973). [Online video] Available: [2021, June 24].

African Noise Foundation: Kaganof & Deane. 2017. White Noise in Eight Amplified Movements (for Clarice Lispector). In Navigating Noise. (Ed.) van Dijk, N., Ergenzinger, K., Kassung, C. Schwesinger, S. Kunstwissenschaftliche Bibliothek Series, Vol 54. Berlin: Buchhandlung Walther König.

Attali, J. 1985. Noise: The Political Economy of Music. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press.

Beckett, S. 1958. Endgame: A play in one act. London: Faber and Faber.

Beckett, S. 1972. Not I. YouTube. [Online]. Available: [2020, April 1].

Butler, G. 1990. Demea. Cape Town: David Philip.

Celant, G. 1967. Arte Povera: Notes for a guerrilla war. In Flash Art, no. 5 (Nov-Dec). (Trans.) Henry Martin. [Online]. Available: [2017, September 20].

Cocker, E. Ethical Possession: Borrowing from the Archives. In Smith, I. (ed.). Cultural Borrowings: Appropriation, Reworking, Transformation (A Scope e-Book). Scope: An Online Journal of Film and Television Studies. P. 92-110. [Online]. Available: [2017, April 27].

Collins English Dictionary. 2014. S.v. ‘surface noise’ [Online]. Available: [2020, April 4].

Davis, C. 2005. Hauntology, spectres and phantoms. In French Studies, Vol. 59: 3, pp.373-379. Available: [2020, September 5].

Derbyshire, D and Bermange, B. 1964. The Dreams. An Invention for Radio, BBC Radiophonic Workshop. [Online]. Available: [2017, April 7].

Derbyshire, D & Bermange, B. 1964. ‘Falling’ from The Dreams, online audio, YouTube. Available: [2020, March 30].

Derrida, J. & (trans.) Owens, C. 1979. The Parergon [Online]. In October, Vol. 9 (Summer): 3-41. The MIT Press. Available: [2017, October 16].

Derrida, J. 1994. Spectres of Marx: The State of the Debt, the Work of Mourning and the New International. (Trans.) Peggy Kamuf. New York: Routledge.

Douglass, F. 1861. Pictures and Progress: An Address Delivered in Boston, Massachusetts, on 3 December 1861. In (ed.) John W. Blassingame The Frederick Douglass Papers: Series One, Speeches, Debates, and Interviews, Vol.3 (1985): 452-53. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Ergenzinger, K. 2020. Acts of Orientation [Online]. In nodegree (Artist’s website). Available: [2020, September 17].

Ernst, W. 2016. Radically De-Historicising the Archive: Decolonising Archival Memory from the Supremacy of Historical Discourse. In (eds.) Ištok, R. & L’Internationale Online: Decolonising Archives. [online]. Available: [2016, April 7].

Fisher, M. 2014. Ghosts of my Life: Writings on Depression, Hauntology and Lost Futures. Winchester and Washington: Zero Books.

Hägglund, M. 2008. Radical Atheism: Derrida and the Time of Life. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press.

Kaganof, A. 1997. Signal to Noise [Super 8mm]. Aryan Kaganof collection. Documentation Centre for Music (DOMUS), Stellenbosch University.

Kaganof, A. 2004. Venus Emerging [HDV]. Aryan Kaganof collection. Documentation Centre for Music (DOMUS), Stellenbosch University.

Kaganof, A. 2010. ‘Anahat’. The Bow Project [CD]. Faroë Islands: TUTL Records.

Kristeva, J. 1997. New Maladies of the Soul. In The Portable Kristeva, (ed.) Oliver, K. New York: Columbia University Press.

Lispector, C. 1992. The Egg and the Chicken. In The Foreign Legion: Stories and Chronicles. New York: New Directions.

Miller, S. 2015. In Defense of Medea: a feminist reading of the so-called villain. In Daily Review. [Online.] [2020, March 21].

Nechvatal, J. 2011. Immersion into Noise. Michigan: Open Humanities Press.

Nicholson, C. 2021. Delia Derbyshire: The Myths and the Legendary Tapes review – playful paean to a musical pioneer, The Guardian, 16 May 2021. Available: [2021, June 15].

Rea, N. 2019. Marisa Merz, the Legendary Italian Artist Who Brought a Woman’s Perspective to Arte Povera, Has Died. In artnet News [Online]. Available: [2020, September 3].

Steyerl, H. 2012. In Defence of the Poor Image. In The Wretched of the Screen. New York & Berlin: Sternberg Press.

UKEssays. November 2018. Feminism in the works of Medea. [Online]. Available: [2020, March 21].

van Dijk, N., Ergenzinger, K., Kassung, C. & Schwesinger, S. 2017. Navigating Noise. Kunstwissenschaftliche Bibliothek Series, Vol 54. Berlin: Buchhandlung Walther König.

van Zyl Smit, B. 1992. Medea and Apartheid. In Akroterion Journal for the Classics in South Africa, Vol. 37, No. 2, pp. 73-81. [Online]. Available: [2020, March 31].

van Zyl Smit, B. 2002. Medea the Feminist. In Acta Classica, Vol. 45, pp. 101-122. Online: Classical Association of South Africa. Available: [2020, March 21].

Verwoert, J. 2007. Living with Ghosts: From Appropriation to Invocation in Contemporary Art. In Art & Research: A Journal of Ideas, Contexts and Methods, 1(2), Summer. [Online]. Available: [2017, May 5].

Medea 1969, Film, (dir.) P. Pasolini, Italy, France, West Germany.

Medea, falling… a poor image reconstruction 2018, HDV, (dir.) N. Deane, African Noise Foundation, South Africa.

Signal to Noise 1997, Super 8mm, (dir.) A. Kaganof, (prod.) F. Scheffer, Netherlands.

Something Wild 1961, Film, (dir.) J. Garfein, Prometheus Enterprises Inc., United States.

Venus Emerging 2004, HDV, (dir.) A. Kaganof (Remix collection), African Noise Foundation, South Africa.

| 1. | ↑ | Transcription of text for voice in my Sonic Poem: White Noise in Eight Amplified Movements (for Clarice Lispector) (2017). A collaboration with African Noise Foundation that is based on the short story “The Egg and the Chicken” (Lispector, 1964). Featured in the interdisciplinary publication “Navigating Noise” (2017: 96-106). |

| 2. | ↑ | “Navigating Noise is a poetic exploration of the means of orientation in space through sound and movement. The installation is a site-specific, interactive sonic architecture through which visitors move freely, navigating its sounds and noises. This leads to subtle shifts in the perception of space.” (Ergenzinger, 2020: online). |

| 3. | ↑ | Referring to The Wolf Man’s Magic Word: A cryptonymy (Abraham & Torok: 2005) and their theory of the crypt as “the burial of an inadmissible experience” (International Dictionary of Psychoanalysis, 2020). |

| 4. | ↑ | A portmanteau of haunting and ontology; Derrida’s term from Spectres of Marx: The State of the Debt, the Work of Mourning and the New International (1994). |

| 5. | ↑ | “What they call a phantom is the presence of a dead ancestor in the living Ego, still intent on preventing its traumatic and usually shameful secrets from coming to light” (Davis, 2005: 374). |

| 6. | ↑ | First produced at the Great Dionysia in Athens in 431 BC. |

| 7. | ↑ | For examples see “In Defence of Medea: a feminist reading of the so-called villain” (Miller, 2015), and “Feminism in the works of Medea” (UKessays, 2018). |

| 8. | ↑ | The line of a poem from my personal archive that reflects the weave of the history of my practice (2008-2020). |

| 9. | ↑ | Noise produced by the friction of the needle or a stylus of a record player with the rotating record, caused by a static charge, dust, or irregularities on the surface of a record (Collins English Dictionary, 2014). |

| 10. | ↑ | Samuel Beckett wrote in 1972: a monologue for stage in which the sole visual on stage is the performer’s mouth. |