NICOLA DEANE

FRAGMENTS By Way of Introduction

Le cercle des fragments ~ The circle of fragments

Roland Barthes, Roland Barthes by Roland Barthes (1977: 92-4)

To write by fragments: the fragments are then so many stones on the perimeter of a circle: I spread myself around: my whole little universe in crumbs; at the center, what?

…

Then if you put the fragments one after the next, is no organization possible? Yes: the fragment is like the musical idea of a song cycle (La Bonne Chanson, Dichterliebe): each piece is self-sufficient, and yet it is never anything but the interstice of its neighbors: the work consists of no more than an inset, an hors-texte.

The ordering principle for this practice-led dissertation is to weave the straight sentences into the fabric structure that is made up of fragments. Fragments informing the structure provide the appropriate analogical mode for my artistic research since I think scrapmatically. Fragments are not usually linked to the foundational principles of building a structure, but rather associated, at least in my mind, with the pieces that survive the ruination of a structure, that may serve as traces and detritus, of its existence and demise. This inversion of expectations with the foundation of fragments provides a perfectly delinked structure for my decentering of the DOMUS[1]DOMUS: Documentation Centre for Music, University of Stellenbosch. archive.

Fragmentation is here a useful term because it always points to one’s limits. Since the self, like the work you produce, is not so much a core as a process, one finds oneself, in the context of cultural hybridity, always pushing one’s questioning of oneself to the limit of what one is and what one is not… By working on one’s limits, one has the potential to modify them. Fragmentation is therefore a way of living at the borders.

Trinh T. Minh-ha, Framer Framed (1992: 156-7)

The fragment may be perceived as more than the whole, since it allows for a hyper-focused view of part of the whole, and so, bears an insight (into the whole), is part of the total understanding – when the whole is dispersed in parts new perspectives arise. Fragmented perspectives may add up to more than the whole, but the fragment is also an entity in itself (a whole in its own right), carrying a clue to what is absent or beyond, bearing a trace or ghost of the whole. The fragment is always haunted. Furthermore, the very surface of any fragment (or tiny brittle shard) may say everything, through the layers and traces of time past, or absolutely nothing… about the now. But before I destabilize the DOMUS, I have to ask: What is this archive to me? How is it centred – on what exactly?

Domus is Latin for house/home, which I find appropriate for the idea of an archive, from the utopian view at least, providing a good home for its records – for its inhabitants to be taken care of, their vulnerable states protected, their prime states preserved and secured for the future. So my basic sense is that this “house/home”, like any traditional archive, is centred on order (both rational and logical), chronology, categorisation, classification, preservation, endurance, discipline, tradition, prudence, security, territory, and possession. “Domestic affairs” fixed by systems acknowledging and prioritizing origins and essences. A decentering of the DOMUS thus invites disorder, irrationality, illogicality, non-linearity, declassification, immateriality, ephemerality… deterritorialisation.

§1 Domus et DOMUS

When I decided to embark on a PhD in Visual Arts, I had been a wife for nine years and a mother for eight. It is difficult to explain why I wanted to do it. It had something to do with my art-making depression, my domestic confinement and responsibilities, financial insecurity and its related anxieties, socio-cultural disconnection, and geographic isolation. But I am not sure about the extent to which any of these things were important, or if they mattered at all. I had completed my MFA at Michaelis School of Fine Art (UCT) four years previously in 2012. The project consisted of a multimedia installation titled A Heritage of Secrets in Confessional Mode by which I cast my split-imagination across the quiet, reflective museum mode of display and the disquieting sensory ambush of live drum performance and strobe-pulse video projection.

WARNING: This video contains flashes of light that may trigger seizures for people with visual sensitivities.

Video component: Portrait of the Artist Thanking Her Detractors (2011)

Sound component: In Conclusion (2012), morse-encoded confession for percussion performed by Niklas Zimmer.

The reliquary chamber: I Am Not (Yet) a Museum presented five illuminated units on the floor bearing confessional curiosities: personal relics cast in wax, paper scrolls and laser-encoded communion wafers. Another work entitled The Penance: an explication (2011) displayed the 10 000 word hand-typed document of a self-induced endurance performance of resistant exegesis to interrogate the “ontological security” of the art institute with a single repeated sentence: i must confess it is hard to no. The live percussion performance of the composition In Conclusion (2012) signaled a morse-encoded secret transcribed for drum kit set-up within the media display room of the installation, accompanied by mute video works that included strobe effect confessional text in Portrait of the Artist Thanking Her Detractors (2011), as well as Code Desire (2010): a stop-motion remix featuring The Happy Home: A Universal Guide to Household Management (1955). Such were the materials and scenarios of my Art Installation practice, and may provide a pre-history narrative to the one encountered in my current doctoral research within the DOMUS archive. As one of my examiners[2]Willem Boshoff observed, my “confessions” were not possessed by an obsession with sin, but rather engaged in “a philosophical evaluation and criticism of confessional strangleholds.” He goes on to describe his experience of the installation providing the following insights,

Nicola Deane interestingly plays on the fact that confessions have an assumed aspect of trust and secrecy. I believe that she considers her own “confession/s” and the secrecy/confidentiality aspects thereof earnestly in the context of both archaic and facetious precedents. Her work blurs the boundaries between what might be serious spiritual responsibility and confessions that might be part of assumed role-play in enticement and temptation. […] In Deane’s work implied “veils” are deliberately created through the shrouding of dim light and deliberately removed when [invited to participate]. I am thoroughly convinced by the way she transforms these realities in the context of the secrecy and disclosure aspects within which her “confessional” operates. She is in control of a most agreeable process of obvelation and revelation.

This response to my work reveals what was important then, still resonates through my practice as research now, that is, my desire to transform realities through playing with codes of masking/veiling and unmasking/revealing. What struck me most about this particular conceptual engagement with the installation, was the recognition that stemmed from his care and attention to the work that continues to mean a lot to me. What does care and attention mean in this respect? What does recognition through care and attention mean? Recognition is no small ask, but I shall return to these questions.

After my examination, my family and I moved to a rural village in the Overberg, where I kept on making art, but in the non-directed manner of an artist not embarked upon an academic programme or working for an exhibition. This kind of art-making has a very specific character, it is a private housebound activity (studio extends to and returns from the kitchen), neither shown locally nor disseminated beyond its site of production, neither object nor subject of any discourse (on mute), not shared but intimately confined to living quarters.

Did this make my art-making more domestic?

In one way yes – my daily rituals and rhythms provided points for aesthetic reflection, and I became deeply invested in conserving the discarded egg shells from my daily cooking practices and the “home economics project” I was involved in: baking goods for sale at the weekly market held in the village centre. The significance of this growing bi-product archive was not yet fully imagined, but the compulsion to store these fragile remains of everyday consumption persisted. But back to the question – in other ways no, since I have never approached art making as a professional activity in a capitalist economy whereby a body of work is developed in terms of a commission or curated vision around a general theme or particular title. Not, at any rate, without reference to my own way of life and exploration of self.

A part of who I am as an artist is my living together with the artist who is my husband. I am an artist’s wife. I am an artist, married to an artist, despite Marina Abramovic’s injunction for artists never to marry each other. What is, if at all, the anxiety of influence (Bloom: 1973) of living as an artist, making art in my private domestic sphere, with another artist? Observing the dynamics in any art school studio could provide an overview of the impact of other artists’ style, method, medium, rhythm, productivity, and personality on that of one’s own. There has to be a certain amount of working tension and a bloody good sense of humour at play. My husband and I, as a result, share a creative history in collaboration, namely:

Virgins: Home Economics Performance (NSA, Durban 2002); SMS: Sanctuary Mental Space Group Show (Centraal Museum, Utrecht: 2003); Nicola’s First Orgasm (5min33sec: 2002); Primal Scene (4min40sec: 2002); Casbah and Back (7mins20sec: 2002); and Diabelli Variation XXXIII (5min: 2003). But the collaboration is embedded in the interweaving of our lives together. Both working from home, our daily life is informed and infused by whatever project or research either of us are engaged in. He is, for instance, continuously engaged in consuming the contents of my writing surfaces (eggshells) for my current research project.

Upon my decision to pursue a PhD I was encouraged by my supervisor that visual representations of the sound archive could inform interesting creative responses. The archive in question, DOMUS (Documentation Centre for Music), is kept under lock and key of the Music branch of the library, housed within the Music Department building, University of Stellenbosch – a repository for various collections related to music made/played/recorded in South Africa. This archive stores various fragments and fabrics of sound, ciphers, scores – compositions of text/image/sound and captured time that I had proposed, could be “reimagined” through various critical art practices to evoke a subversive and (de)constructive site for reflection. There is a wide range of categories that may be identified within this domain such as traditional music, classical music, indigenous music, choral music, jazz, popular music, arranged music, improvised music, struggle music, folk music, regional music, composers, instruments, broadcasts, and so on. Given the tortured, complex sociopolitical history of South Africa, these categories, however useful, struck me as problematic in that they perpetuate divisions within a society that is still imbued with its colonized conditioning and further burdened by its lingering apartheid past/present. And so my enquiry aimed to assess the existing record-based knowledge to manifest an understanding of this body of historicized music (in the DOMUS collection) through artistic strategies of encountering and unveiling what lies behind and between that structural organization (of an archive), that is often centered around deeply embedded essentialist stereotypes and clichés.

From a theoretical desire to decentre this archive, that is, to destabilise the “assumptions of origin, priority, or essence” (Merriam-Webster, no date), my creative work took an unexpected turn. The work suggested that the domestic space, a space that is ideologically centred on a particular version of womanhood and constructed femininity, bears metaphorical and metonymical resemblance to the centred archive. Becoming aware of this, made it possible to think about decentering the archive in a very different way to the way in which I had initially conceived of it, as a decolonial project.

If we do take the archive as metonymy for colonialism it can be argued that white women’s relationality to the colonial project needs to be acknowledged – in our active perpetuation of the project in the colonial frontiers through the set up, ordering and domestication of the home space and the belief systems of empire, even as we may have been oppressed figures within our home spaces.

My heritage is simultaneously entwined and detached from the colonial project (born in Scotland, to a working class family, and emigrated to a colonised and racially segregated South Africa before the age of two), so I consider myself a decentred citizen of South Africa. I feel somewhat estranged from the role automatically applied to the identity white woman: her complicity in affirming the unbalanced power dynamics of the colonial project and the subsequent apartheid system. As a child growing up in this adopted territory, I always felt like an outsider and feeble witness to a radically foreign classification system that was based more explicitly on race than class, but which rendered me complicit nonetheless.

In her introduction to “Doing it for Daddy” (in Real to Reel: Race, Sex, and Class at the Movies, 1996), bell hooks recounts an interview with one of Charles Manson’s lovers who was asked what sexual intercourse with the man was like: “He said, ‘Imagine I’m your father’. I did. I did. And it was very good”. Hooks conveys her delight with this confession: “because it reveals quite innocently the extent to which patriarchy invites us all to learn how to “do it for daddy”, and to find ultimate pleasure, satisfaction, and fulfillment in that act of performance and submission” (hooks, 1996: 83). I think hooks brilliantly sums up the problem of such a psychology that unites women across race, culture and class, which is what I am interested in since I cannot speak for South African women of colour. I can only speak from my experience of registering “whiteness” and becoming (officially) “white” upon my entry to South Africa, based on the classification system imposed by the government at the time on its citizens.

One option available for decentering the archive could be by decentering the domestic. At the same time, the centred archive provides a vocabulary and an epistemology that discloses certain hidden truths about the domestic. Unmasking these truths through (a decentering of) the archive, could have unexpected resonances in how to (re)think the domestic. In this way, my creative work has led to the discovery of a domestic-archive dyad, which I problematize and explore in the work presented here.

§2 Research Problem

Excerpt from my collection of Cross-stitch Poems:

The problem is…

The archive can never be important enough

The problem is…

The PhD can never be important enough

What is it I am evading?

The problem is…

I have no problem

There is nothing to solve

There is no meaning

In any of this

There is no problem

I am evading for that reason alone

The problem that I may

And the problem that I may not

Propose

The problem in the case of the archive

(the archive and eye)

Is that it traces what is too late

The closer one is to the surface of the archive,

the further one reaches…

Cannot be further from the truth

This is what I know

This is all that I know

I know Nothing…

No, in fact not

I am from Scotland,

Born in the ghost town

of Singer sewing machines and shipyards

The very first place I abandoned

in my pre-verbal phase

I grew up with an alien consciousness[3]In fact it’s a neither-nor-conciousness

From June 1980 – February 1997

in Johannesburg, South of Africa

A particular kind of alien territory

Because for every alien

in any territory

that is

Outside the homeland

Adoptive or transitory territory

is Alien

one’s operation is always from a position of Other

either on the inside

or visible on the outside

one is always wearing a mask

a buffer

an alien-conscious[4]In fact alien to homeland too, but not via the skin skin

or insider/outsider traits

of the inappropriate/d other[5]“We can read the term ‘inappropriate/d other’ in both ways, as someone whom you cannot appropriate, and as someone who is inappropriate. Not quite other, not quite the same” (Interview: Trinh T. Minh-Ha, 1998).

Outside/Trans-territory/Border

Home/Domus

Alien/Other

What is the home?

What is the domestic territory?

Of one’s heart for instance

Of one’s mind

Of one’s… dare I say it?

Life force?

And what is the heart centre of the archive

(named DOMUS)?

What is its life force?

Its system of access?

Its network and arterial structure?

Its conception, or its translation?

At least that is all that I imagine(d)

Before I was allowed in

§3 Imaginarium under embargo

I have to begin this navigation with the imagined DOMUS (that is, the one I built my proposal around before stepping foot into it), of which I was convinced consisted of glaring holes, restrictive categories, and a recognisable “centre” (where one would likely find a “lost-property” box of masked gems). The evasive DOMUS consists of the administration block around access to the archive – I wanted to engage a general survey with the materials of the archive within the physical confines of the main storage room as opposed to the more common research requests that the archivist handles regarding particular items from the collections as categorized by finding aids, and to be perused within the music library setting. The regular approach would not work for me since I had no idea what I was looking for – my main objective was to discover the unknown by my own embodied map, to find what lay beyond the formatted finding aid. In short, gaining “free” access was a protracted affair that only served to build up an appetite of expectations for the actual DOMUS that I finally set foot in on the 18th October 2016. I then went through a series of sentiments with my physical navigation of the space in the company of the archivist outlining the layout of the space. I was shown a list of items that were classified “under embargo” including a folder within my husband’s autobiographia and ephemera: the Kaganof collection. The absurdity of being disallowed access to something related to my husband struck me unexpectedly, though I continued to listen intently to the archivist’s fluid track through the aisles gesturing sections and sub-sections, dropping names and abbreviations along the way, and finally presenting me with a music stand bearing a request form, a square stool and latex gloves in a small corner of the main storeroom of the DOMUS archive.

Supervisor #1: cover your difficulties, disappointments, panic, uncertainty, fever NO ABSTRACT WRITING.

Supervisor #2: Let’s ditch this absurd notion, for fuck’s sake.

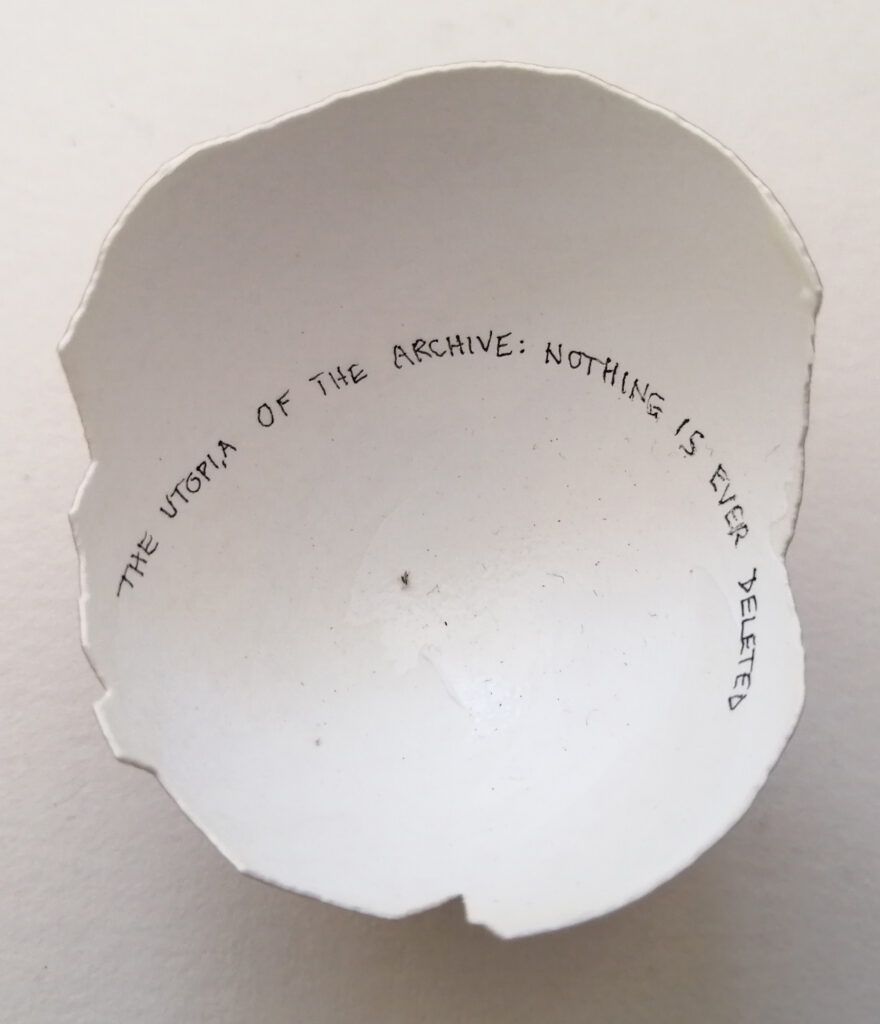

§4 Utopia of the archive = nothing is ever deleted.

Too much stuff

What does it add up to?

Textures, hues and tones of time passed

Stacked, bound, strung-up, scratched, marked, torn, taped, masked

Too much to sieve through

Will I turn to a poetics of space?

But it turns out to be too confined

Too much like a shell-dwelling…

Instead I turn to a poetics of surfaces

A superficial reading of surficial material

Surficial conditions

Surficial sediment

Surficial deposits

Surficial noise too

§5 Literature review

L’Internationale Online’s Decolonising Museums (2015), Decolonising Archives (2016), texts around Decoloniality and Border Thinking, particularly Walter Mignolo: The Darker Side of Western Modernity: Global Futures, Decolonial Options (2011); ‘Delinking’ (2007); Decolonial AestheSis: Colonial Wounds/Decolonial Healings (Mignolo & Vázquez, 2013); “Theorizing from the Borders: Shifting to Geo- and Body-Politics of Knowledge” (Mignolo & Tlostanova, 2006); Aníbal Quijano’s Coloniality and Modernity/Rationality (2007); Ngugi wa’ Thiongo’s Decolonising the Mind: the Politics of Language in African Literature (1986); Achille Mbembe’s Decolonising Knowledge and the Question of the Archive (2015); Wolfgang Ernst on “Radically De-Historicising the Archive: Decolonising Archival Memory from the Supremacy of Historical Discourse” (2016); “Tacit Narratives: The Meanings of Archives” (Ketelaar, 2001); as well as texts about artistic engagements with archives: Archive Stories: Facts, Fictions, and Writing of History (Ed. Burton, 2006); What is research in the Visual Arts? Obsession, Archive, Encounter (Holly & Smith, 2008); The Big Archive: Art from Bureaucracy (Spieker, 2008); Cultural Hybrids, Post-disciplinary Digital Practices and New Research Frameworks: Testing the Limits (Gates-Stuart & Wolmarck, 2004); “Records and their Imaginaries: Imagining the Impossible, Making Possible the Imagined” (Gilliland & Caswell, 2016); and relative texts around sound/music such as Sound Art: Beyond Music, Between Categories (Licht, 2007); From Music to Sound: Being as Time in the Sonic Arts (Cox, 2006).

§6 Touched

Amidst all of this detached reading, I started making my first work. I was so overwhelmed by the anonymous sea of archival material of the DOMUS storeroom that I was compelled to capture that vertiginous sense of looking so closely at the multitude of materials that one’s attention dissolves. I performed these movements of photographic capture through the storage quarters of DOMUS, of the extreme details in surfaces of all the visible records. Surfaces carrying traces of time and evidence of having been handled – the very traces of touch. My art practice has always been invested in the sense of touch – the making process is never detached for me, I like to handle materials and manipulate forms that generally emerge from an organic mess. The surfaces, textures and minute details in my work always carry that pleasure of touch. Since archival records are more or less untouchable, and justifiably so – these traces of handling etched on the surfaces of the materials captivated me.

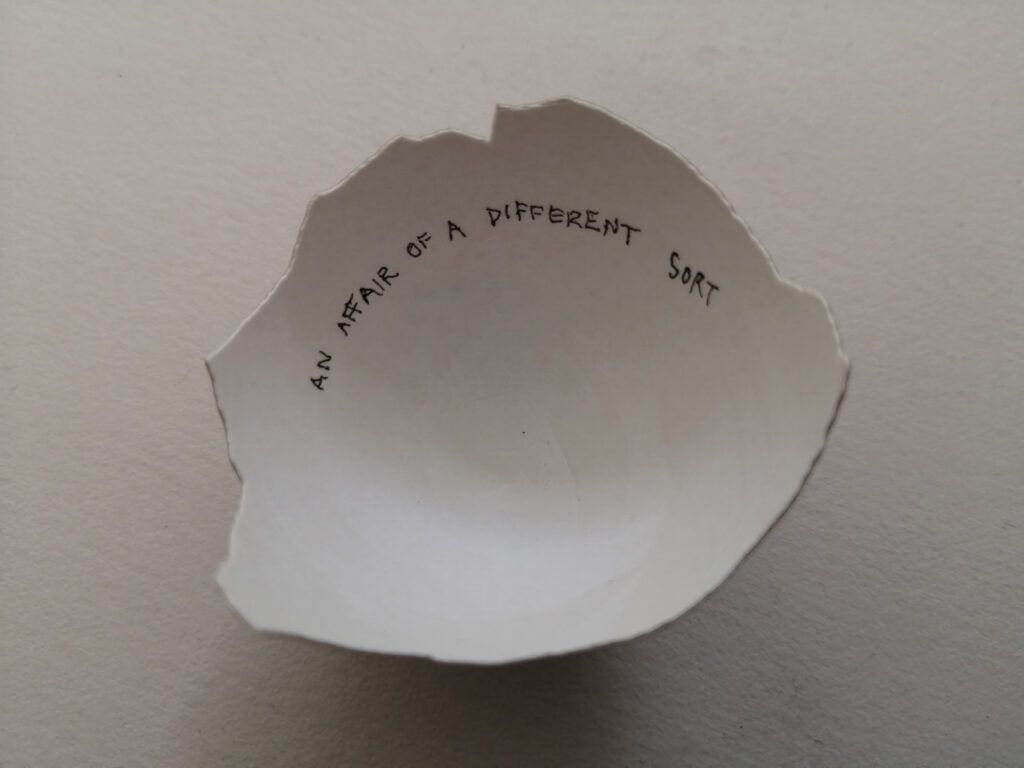

§7 An archival affair

A very superficial affair when compared to the more scholarly approaches to engaging the archive. I have a different approach to extraction and capturing, I also like to compose many layers of information to create a code by, but only to reveal, in this case, that my real interest is in the surfaces of this archive called DOMUS (that funnily enough houses a part of me, but more on that in a moment) – the work I show you now reveals an obsessive and urgent affair with the archive’s materiality rather than the contents of its records. I was fixated with capturing all surfaces of the outer skins, sheaths and containers of its records, to create a new map to navigate by – presenting my peculiar style of decentering the DOMUS archive. I took that suggestion “make a map of your proposal for the journey of your research” rather literally. I kept my attention to the left, and followed an uninformed circuit of logging the surfaces of the archive – instances and frames. It was important for me to take still photos and not simply film the archive, as I wanted to document as closely as possible all the nooks and crannies of the containers of contents – that say nothing, and everything.

I lacked any direct passionate interest in the contents, and found no appeal in the various categories that make up an archive’s architecture, or vertebrae. I simply studied the surfaces. Whereas the other studies discussed in the other passages delve into the more cryptic levels – producing more figurative and fictive works that capture many “absent-centre-selves”, as a way to map a counter-narrative or counter-archive, perhaps a counter-composition in fact, on how the other half lives… or in this case how my other half lives – in the DOMUS archive.

When I entered the void of this project I proposed all kinds of nonsense so that by the time I entered the actual archive I was hopelessly lost, right up to hitting the feared blank wall indicating: I am a wandering researcher with no “centred” interest in this particular archive. What could be extracted from this sorry superficial affair? An escape by digging deeper on the spot? Just what would I find if I stood still and stopped looking for… nothing but the “absent centre”? From there I figured that the only way through the blank wall was by way of the mirror – the practice of self-portraiture – at least that is how the creative component of this project began. So I proceeded to dig up some form of memory of my own – and yet it is not technically nor materially a memory, but a short film rather – a film of which I am the object and subject, the framer and the framed. This excavated film from the bowels of the DOMUS is entitled Primal Scene (2002) that documents a real space and time (from my past), as well as a framed space and time of the artwork that is a portrait as well as a self-portrait. I am entitled access to this document since it is my very own artefact.

The creative engagement with the archive has morphed since that first encounter, playing with many “absent-centre-selves” through the use of montage, remix and self-appropriation. I have permission to play with this particular collection’s material, at least while I wear this ring, but a large portion of the material I appropriate is remix material. There is also a tension in the reworking of this material with the original editor of the material, and he has to shift the frame to suit my perspective. In effect I am creating a pocket within the archive, a pocket within a particular collection – an invagination of the archive, in which I plant my own frames.

Is there a way to be more authentic with my research? Can I speak through the voice I was given alone? That is what a practice-based PhD process reveals the anxiety around, or so it seems, and I cannot deny my suspicion that nothing is, as it seems. My work is the voice I speak through instead, work that bears many voices and different registers of my being/thinking/doing – many ‘absent-centre-selves’ on the shelves. My work embodies the mask of many voices, Kant’s critique I critique through other phallogocentric voices, in order to dance my way through this maze of theorizing my practice. That is at least what I initially perceived the PhD process to be about – which unsettled and challenged me, but also depressed me. However I also need to grow up and face the music. Mind the pun. And so, through my own voice, disguised by various agents that include Clarice Lispector, Anne Sexton and Jean Rhys, I attempt to code, veil, decode, recode, fragment, and fracture the sense of self in the art-making and theorizing process. I apparently like to layer things to such a degree as to reveal that the surface is where it’s at, or where I want to be kept. Since I have no real interests at all – instead of sinking into the pit of existential crisis, instead of quietly going off to bury myself – I am compelled to make art, to attempt to frame the chaos of this lack.

Framing is what I am invested in, providing an aesthetic frame and framing the archive (I accuse the archive of all kinds of sense-making crimes, particularly its categorization of knowledge). I frame by cutting in and out, by rearranging space and time through compositions of image, movement, sound and text. The surfaces can become mesmerizing in the process of observing one’s self-confinement.

§8 Tympanic membrane

In the abstract proposal phase of this project I aimed to use the metaphor of the membrane, to bridge the “membranic archive” with the tympanic membrane of the ear, which facilitates hearing – the opening through which sound and music penetrates the body. The Edmond Jabès quote, “through the ear, we shall enter the invisibility of things” (Jabès, 1984: 63), brings to my mind the Bardo Thodol, loosely translated as “Liberation Through Hearing During the Intermediate State” (as opposed to the West’s version The Tibetan Book of the Dead by Walter Evans-Wentz, 1927).

Brazilian writer Clarice Lispector’s short story “The Egg & the Chicken” (1992) is her most mysterious work – she admits so herself in her last recorded interview in 1977 – and so this provided the most influential of gems in the early phase of my research, linking directly (even literally) to my compulsive collecting of eggshells. Her metaphysical meditation upon the egg and the hen I found illuminating and stimulating regarding my “eternal return” to the kitchen of my own practice, and the interior, secreted space of the mind. My art practice has always extended from my most intimate, personal and domestic activities, so if I am to conduct a doctoral study around my practice, it is imperative to situate the study at the heart of my own home: the kitchen.

§9 Imagine/Imagined

My research is fractured because

My art making is fractured because

My living is fractured because

My thinking is fractured because

My breathing is fractured because

My being is fractured because

My archive is fractured because

My heart is fractured because

All I see in the archive is fetishized residue of ruins

The preservation of original records… for research purposes

Chronology

Epistemology

Hauntology

Cosmology

§10 Imagine(d)errida

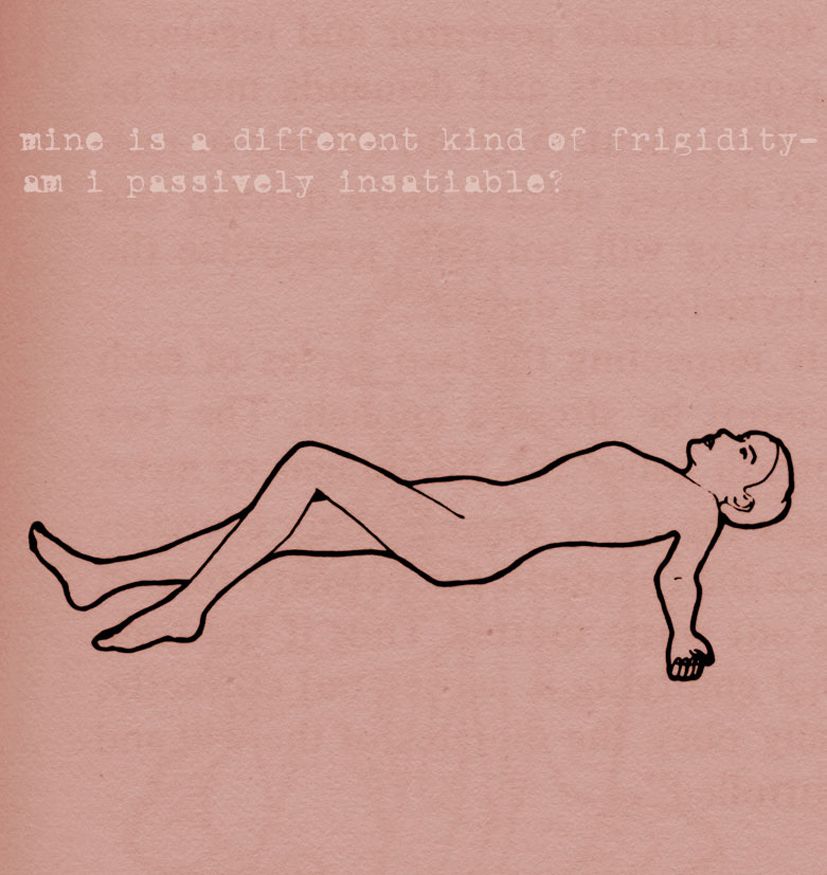

At which point does the active become passive?

“Différance is not simply active (any more than it is a subjective accomplishment); it rather indicates the middle voice, it precedes and sets up the opposition between activity and passivity,” says Derrida in his Speech and Phenomena (1973: 130). In the context of Feminism and Deconstruction this middle voice is described by Frances Bartkowski as “one in which the subject-verb-object relationship is de-centred. It abolishes distance, and may therefore be seen as the form in which a distinct erotic component is present” (1980: 72).

§11 Process

I would like to discuss my process in terms of four phases:

The first phase was that of capturing through Surfaces – to produce an audiovisual navigation of the site of study (Molteno Room, the main storage quarters of the DOMUS archive): On the Passage of a Few Ants Through a Rather Brief Unity of Time. The second was that of the Egg – the gestation phase if you like, which generated the first personal work: “Through the ear we shall enter the invisibility of things”. Through the tympanic membrane of the ear canal, a bridge was formed – literally portrayed in the bridge scene of my third audiovisual study: Medea, falling…a poor image reconstruction from my third phase, namely Noise. Within the Noise phase of my practice a lot of work was generated to develop a series of iterations of audio and visual montages and remixes, that includes my sonic poem: White Noise in Eight Amplified Movements (for Clarice Lispector) – in order to fabricate an archive of fragments that by nature are never whole, never completed. This I performed unconsciously, in the drive to play more freely with materials of an archive that in this case (of DOMUS), is housed, monitored, administrated, preserved and controlled by the University Library. The universal rule of silence binding all libraries across the globe provides an ironic slant to this case of a music and sound archive being under the charge (lock and key) of a library, albeit a Music Library division. Curiously, this may have in fact provoked my rebellious interest in noise, to provide an utterly distinct aperture for such an archive, in order to perform active interrogation and destabilization of this particular confined and conservative territory.

This body of fragments all bound by Noise contributed to the realization of the fourth phase of my process, that of the Mask, noise ends up masked in the final work, An Autopsychography of a Mask in which all the fragments of the research process are sewn together to create a counter-narrative that simultaneously bears and defies all categories or genres, present and absent in such an archive, that claims to “promote music in South Africa and Africa”, and to centralize music collections “as an important part of a broad South African heritage” (Online: DOMUS website).

§12 The heart of the matter

Part of my struggle with writing about what I am doing and undoing brings on the gnawing sensation that the writing will kill the pulsing heart of the art. I know that this is not a real struggle in the grand scheme of the world, or even in the grand archive of that world, but it is an inner surreal struggle that somehow impacts profoundly on the material me – so much so that the only way to survive the wounds of the surreal is to frame it. At least that is the only (open) window I can imagine to materialize the frame.

Never does one open the discussion by coming right to the heart of the matter. For the heart of the matter is always somewhere else than where it is supposed to be. To allow it to emerge, people approach it indirectly by postponing until it matures, by letting it come when it is ready to come. There is no catching, no pushing, no directing, no breaking through, no need for a linear progression which gives the comforting illusion that one knows where one goes. Time and space are not something entirely exterior to oneself, something that one has, keeps, saves, wastes, or loses.

Trinh T. Minh-ha, Woman, Native, Other (1989: 1)

These films are études, studies in audio-visual experiments with time and space, rhythm and movement. They are the result of these frames strung together to represent a surreal experience constructed – fabricated, but not manufactured – to be experienced. The film viewing experience is sensation-stimulus. Spectatorship is an interesting field to navigate. I do not aim for narrative structure[6]“Fragmentation and discontinuity, then, comprise a tool that these artists use to allow for polyphonic narrative structures” – J.K. Odin (1997: Online). but would rather create a trip along the DOMöbiUStrip. It is a script, and it is a score, and it is a thesis. What is the substrate? Noise.

NoiseChaosMythMaskBorderSurface

§13 the heart of chaos

In an ambitious archive things are neatly contained, accounted for, treated with care and attention, to mind the gap of chaos. I believe art provides a frame or channel for the chaos – that the composition process is really a productive wrestle with chaos rather than a denial or suppression of it. Do I make art to construct a theatre to escape to?

It takes a PhD to know

Michelle Gurevich, “Woman is still a Woman” (2014)

What apes all understand

When all is said and done

A woman is still a woman

The point of invagination is that it generates production – chaotic or otherwise – production of the theatrical pocket.

§14 I am trying to generate/replicate/illustrate

The fascinating gastrulation process to reflect on

Our “fully materialized” sense of being…

The source of my knowledge generator is

The source of my knowledge projector

I use the study phase to project ideas towards

That is the value of my process

My eternal return to blindness…

How to avoid the categories?

Scurry along the surface like a creature of decay

The real experience of the aisles, corners, pockets, folds…

I am merely representing an experience of the archive

It may be viewed as a map,

A Möbius trip,

Or by your own design

Cerebral or haptic response

The archival account

The theoretical account

The fictional account

Everything accountable.

How does one rupture the dispositif?

By détournement?

§15 Détournement[7] Based on Rudolf Schwarzkogler’s Selected Scores for Unperformed Aktions (1965-69). from my archive (2011): typewritten text and bone prints on Fabriano cotton paper.

§16 Archiving Time and the Fabrication of Memory: decoloniality, delinking & vulnerability

I propose to make a digital curation of surfaces decentering depth charges – collapsable, expandable, invaginated – that is a catalogue of an archive that doesn’t exist yet and shines a salvationary light on my domestic bliss. The catalogue invents the archive. The archive catalogues the domestic. This is in fact, what is always going on when we think and do “history” – the present invents the past. And there are as many pasts as there are presents – there is not only one strand, the multiplicity of threads is always being formulated, simulated and sewn into the many nows and mediums of the present. This is key to unpacking the complex concept and potential of digital materiality.

MEMORY IS A COMPOSITION. The digital curation shall be a composition, which invents the archive. One becomes a self by composing the elements of what one has experienced into a narrative that we call our story, the story of our lives – but it is never one story because it is never one life that represents a history. This project hopes to provide a clear indication of how the senses invent the past – the senses colonise memory and determine what becomes the now.

MUSEUM OF/FOR THE SENSES: Digital material(ity) in provocation of the senses…The exhibit infuses the archive with the senses. My interest lies in digital installation practice as a new sensory engagement with the audience. Fabrication actually allows for the return of touch – for the materiality of all digital archive surfaces to be invented, by a process of mapping, thereby inventing the future – to have created: a new past. De-linking from the primacy of the heroic sense – “sight” which the autoptic white western gaze privileges – is imperative. There is some concern for the desensitization towards one’s history – informing a sanitized and cauterized history of representations. Therefore sound actually battles vision in other versions of a future/past, when considering the curated whole as a work of translation – speaking in relation to the present – where fiction and non-fiction may meet.

THE FABRIC OF SOUND.

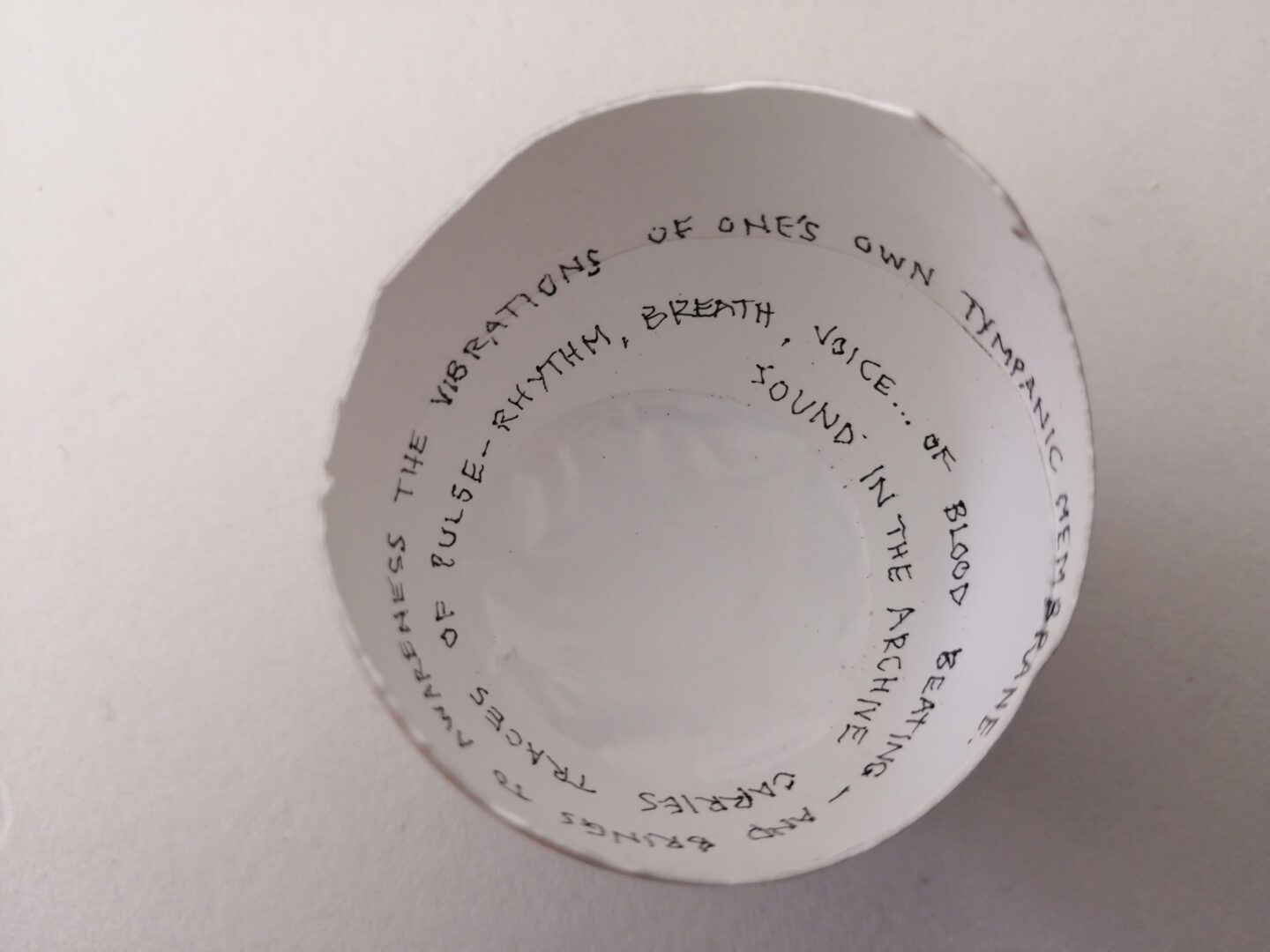

The pulse of a particular history… through sound. Sound in the archive carries traces of pulse – rhythm, breath, voice… of blood pumping a beat – and brings to awareness the vibrations of one’s own tympanic membrane. See Hear Speak no evil. How may the archivist avoid sanitizing the past when creating a new archive of the senses? Particularly with respect to consciously avoiding the previous privileging of an object-based history, a history that has always foregrounded the material as real and proper. In other words, can there be an archive of experiences, and can these experiences somehow be collated without taxonomising them, without reducing them to categories?

THE ARCHIVE MUST BLEED. Notion of the bleed, in image and sound: bleeding across categories opens up the possibility of interrogating the notion of categories themselves. So one possible decolonial option of working with the archive is to re-invest it with an ability to bleed, to break across the rigid taxonomies and artificial fictional separations between categories. My Master’s exhibition sought to challenge past Museum practices of display and categorisation by reviewing the value of the self (private domain) in relation to the hierarchical value systems of the institute in the public realm. I intend to continue my research in this area, by calling into question knowledge systems of our colonial past, through the notion of fabricating memories – the process of re-membering time through lived experience. Memories Can’t Wait[8]Song title from Fear of Music album by Talking Heads (1979), also the title of the Symposium held in 2012 at International Center of Photography, New York that sought to investigate various artistic strategies “to rethink ways to produce, document, and archive forgotten, ambiguous, traumatic, or marginalized memories.”

Available: [2020, August 25].

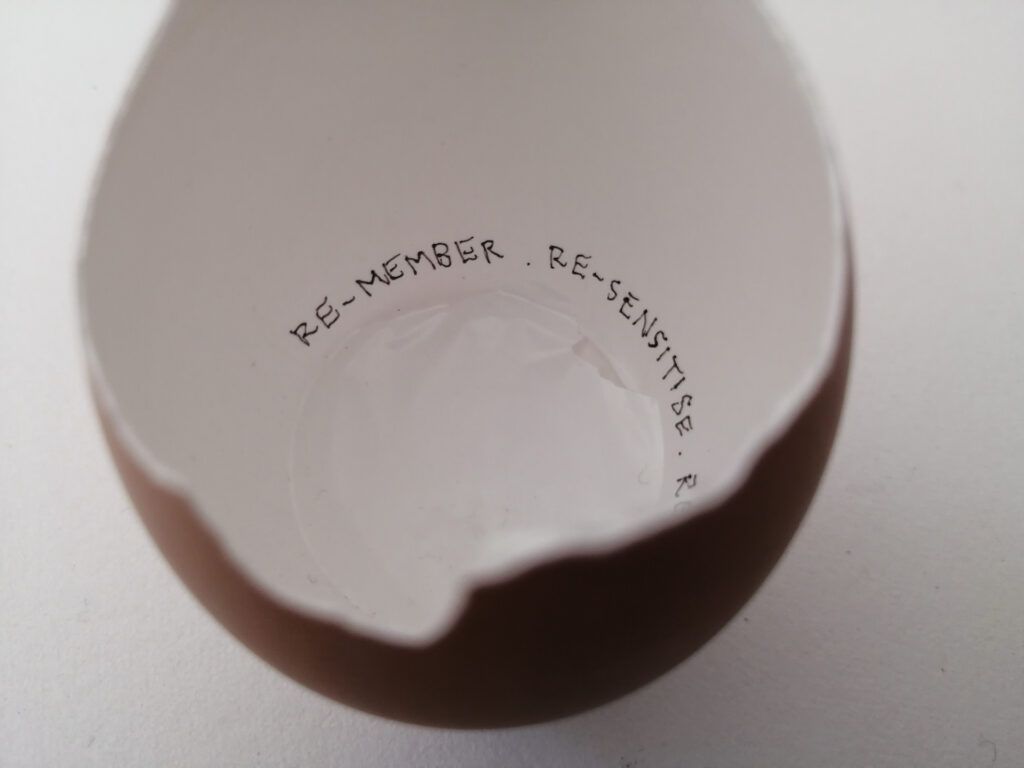

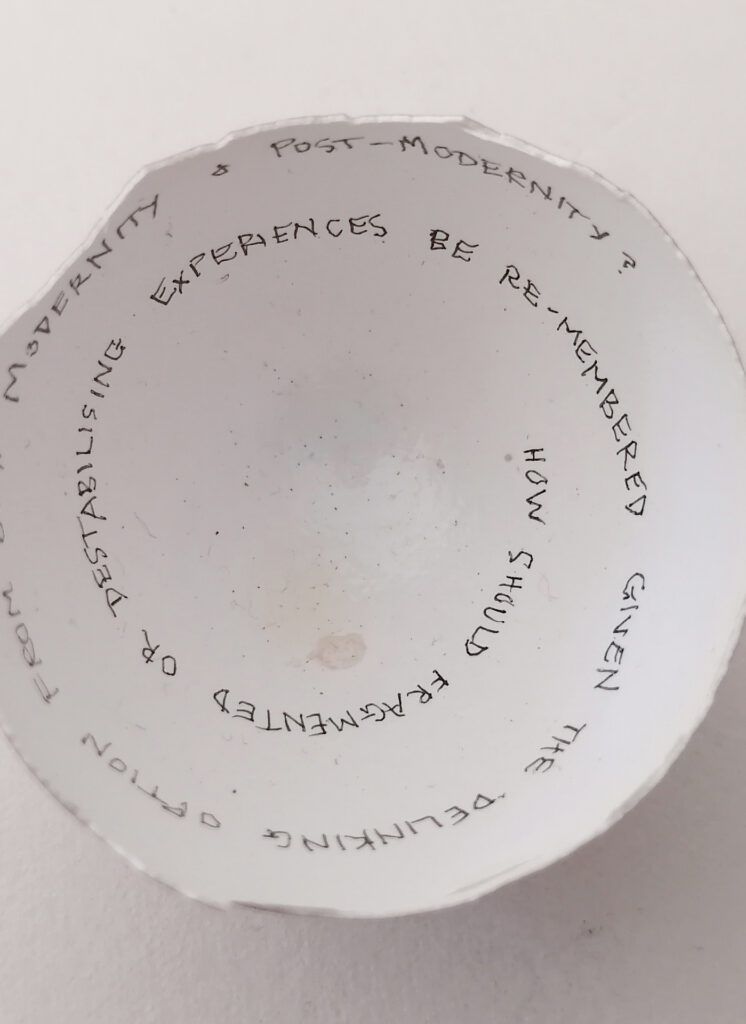

Re-member. Re-sensitise. Re-nascence. I aim to interrogate the role and power of the Archive in manipulating time and collective memories. How should the archive engage with marginalised memories in the context of decoloniality? How should suppressed histories be re-animated in terms of decolonising? How should fragmented or destabilising experiences be re-membered given the delinking option from both modernity and post-modernity?

I see that I’ve never told you how I listen to music – I gently rest my hand on the record player and my hand vibrates, sending waves through my whole body: and so I listen to the electricity of the vibrations, the last substratum of reality’s realm, and the world trembles inside my hands.

Clarice Lispector, Água Viva (2012: 5)

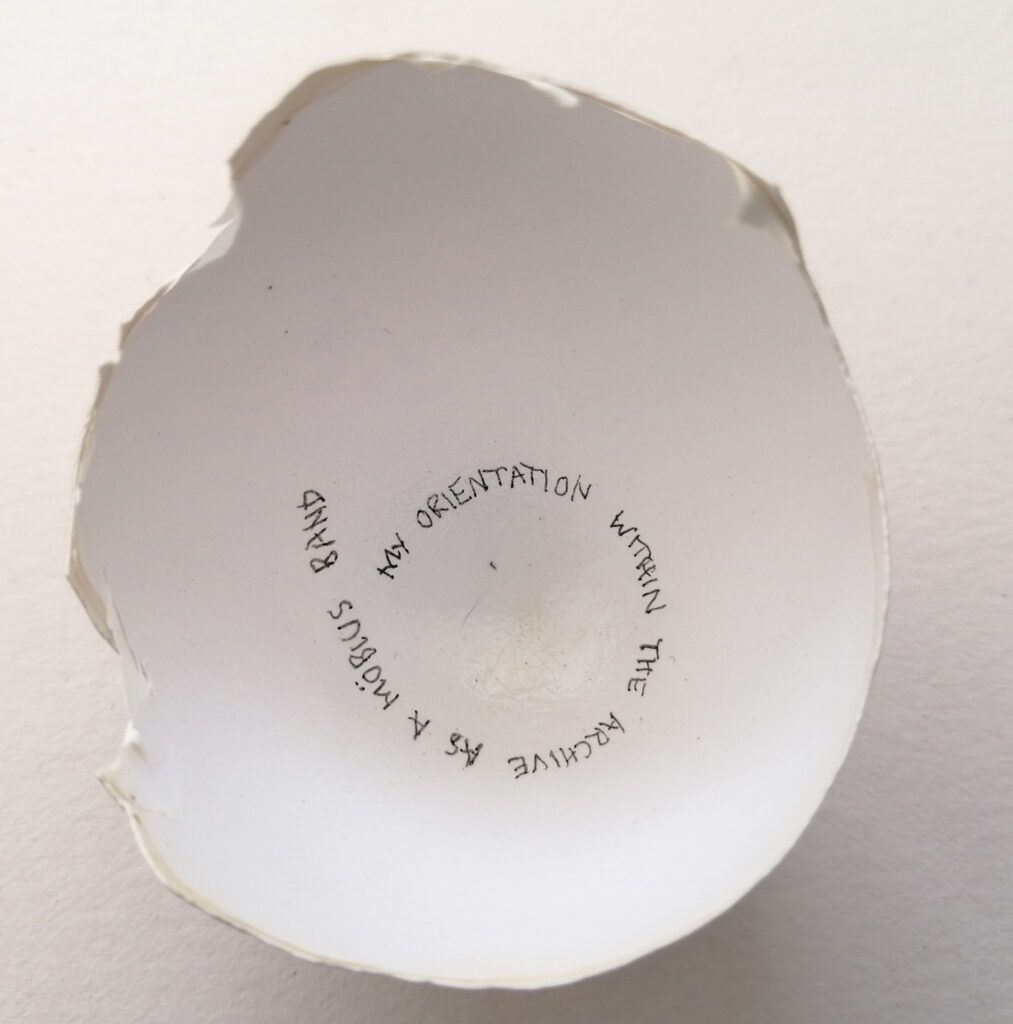

§17 Orientations

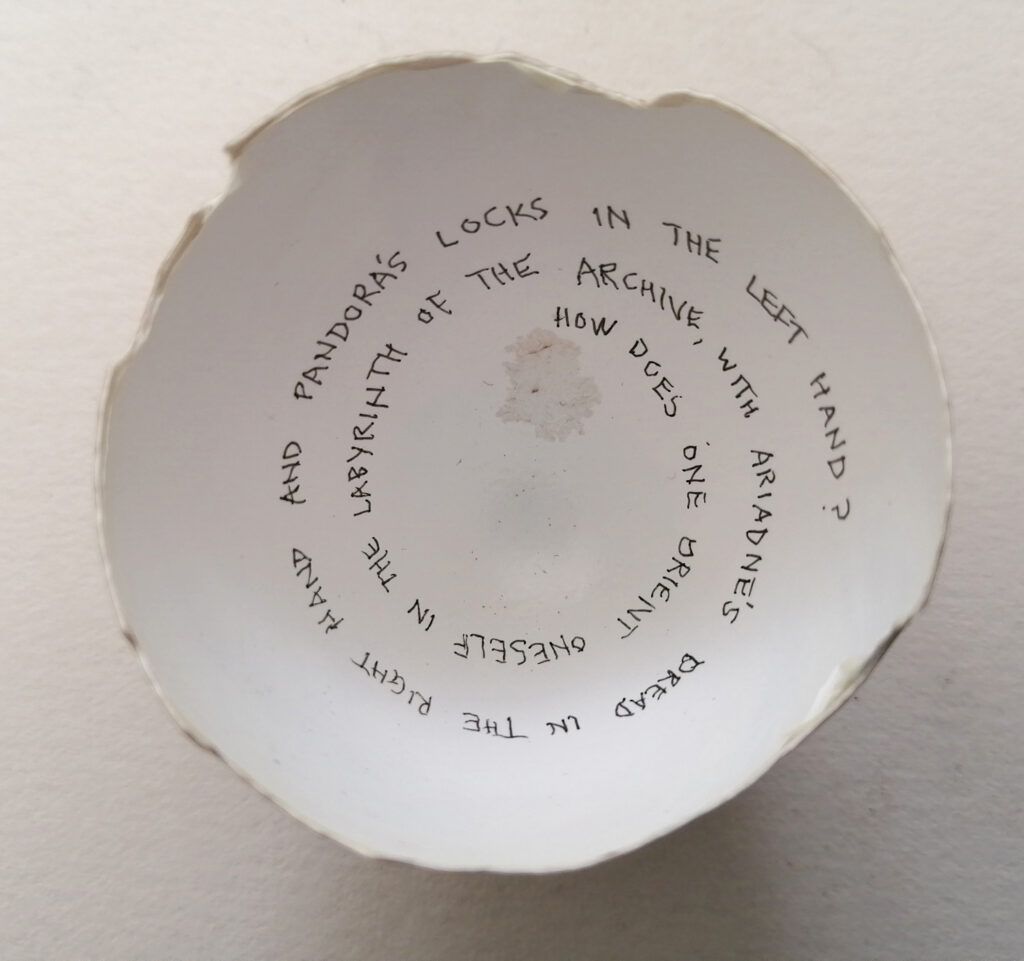

Once in the archive one fears one’s insignificance expand across any number of materials, amongst collections of the deceased, or soon to be deceased. What remains of time and space once the pulse of life has expired? What if the archive has nothing to offer me? Only because I am a subject with no quest of value? How does one orient oneself in the labyrinth of the archive? With Ariadne’s dread in the right hand and Pandora’s locks in the left?

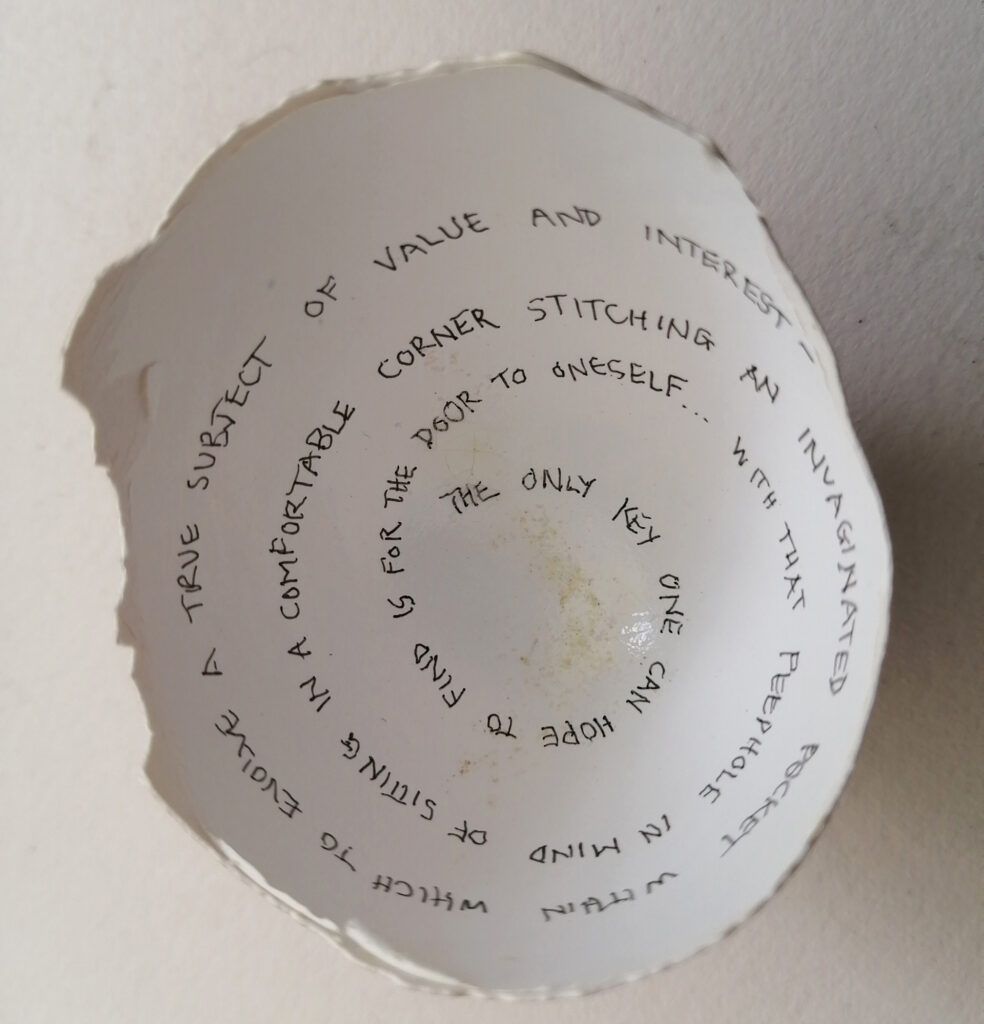

The only key one can hope to find is for the door to oneself. With that peephole in mind: sitting in a comfortable corner stitching an invaginated pocket (as opposed to an appendage), within which to evolve a true subject of value and interest. One has to make a journey of the self to the self as a framed self – as an authentic reflection of the study as it demands original disclosure.

My orientation within the archive as an ant

My orientation within the archive as a mirror

My orientation within the archive as a parergon

My orientation within the archive as a Möbius band

My orientation within the archive as a criminal profile

My orientation within the archive as an abject subject

My orientation within the archive as an other object

My orientation within the archive as evidence

My orientation within the archive as agent

My orientation within the archive as trace

My orientation within the archive as

A disemboweled body

Of scattered contents

And categories…

§18 There I lie

framed

in the archive

Put to rest

but luckily

my fantasies of dying

tie-in

with my dreams of falling…

upright

There lies my husband

his profile

in containers of all kinds,

all familiar yet abstract,

since he is not dead yet.

I cannot help but feel

some nausea

at the sense of loss

to come.

The dread, attached…

and as useful as an appendix

I must make it out of this archive alive

Make must your Master

§19 The fragment as abject trace…

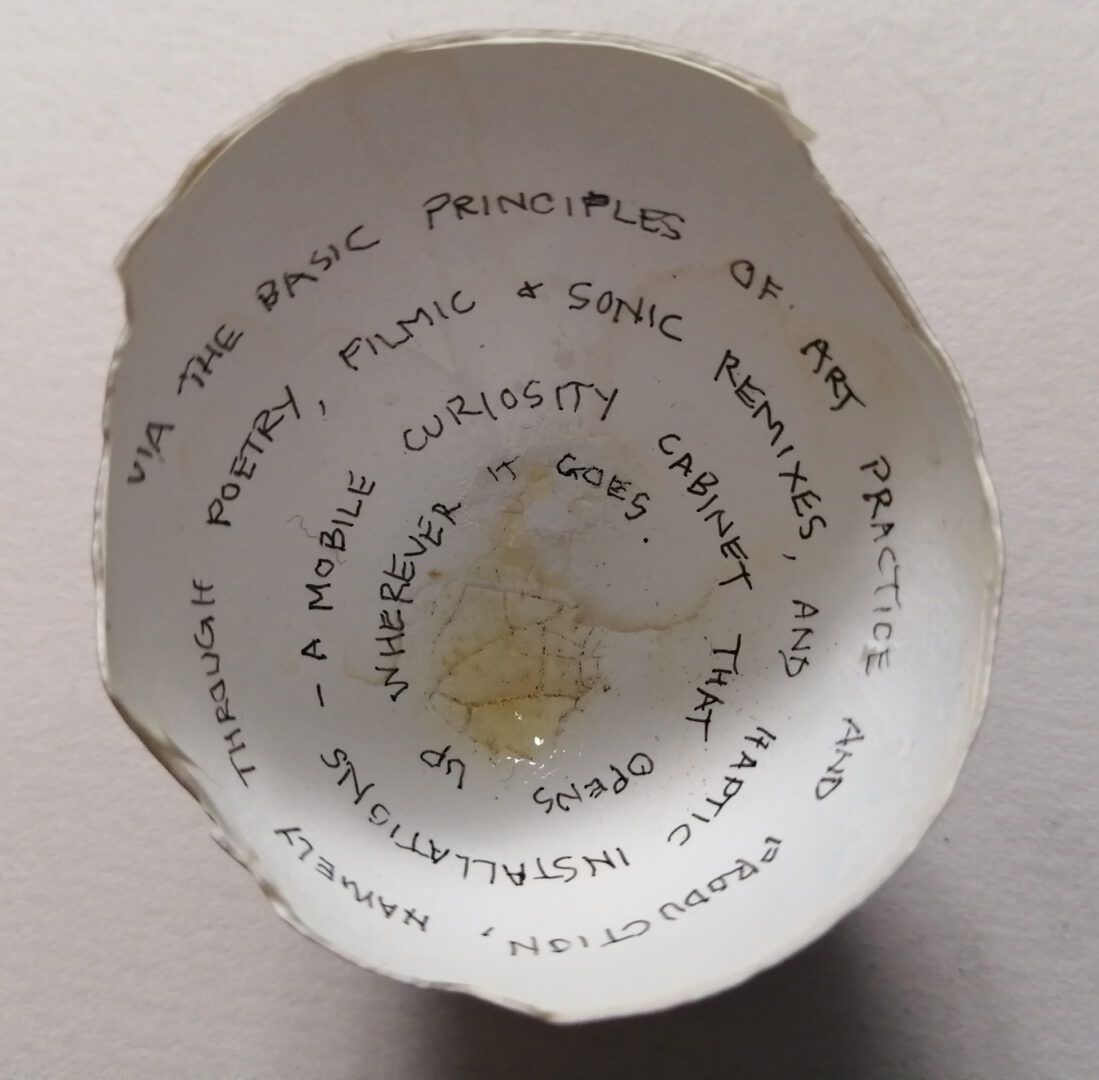

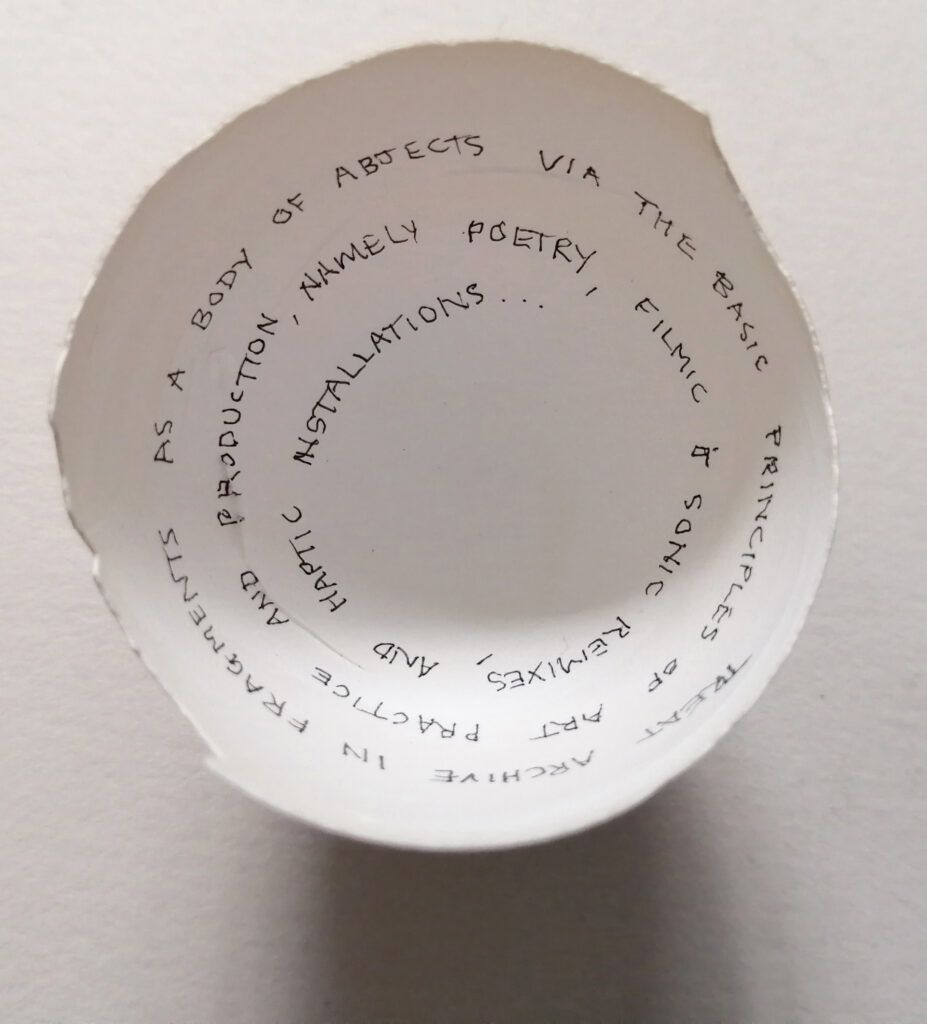

Treat archive in fragments as a body of abjects via the basic principles of art practice and production, namely, poetry, filmic and sonic remixes, and haptic installations. A curiosity cabinet is presented – a mobile curiosity cabinet that opens up, wherever it goes. A hall of mirrors & egg shell carpets – the material destruction of the fragments of time (catalogued, archived), while being walked upon, is amplified so as to approach the border of noise; feedback; surface noise; signal to noise; white noise; and noise black.

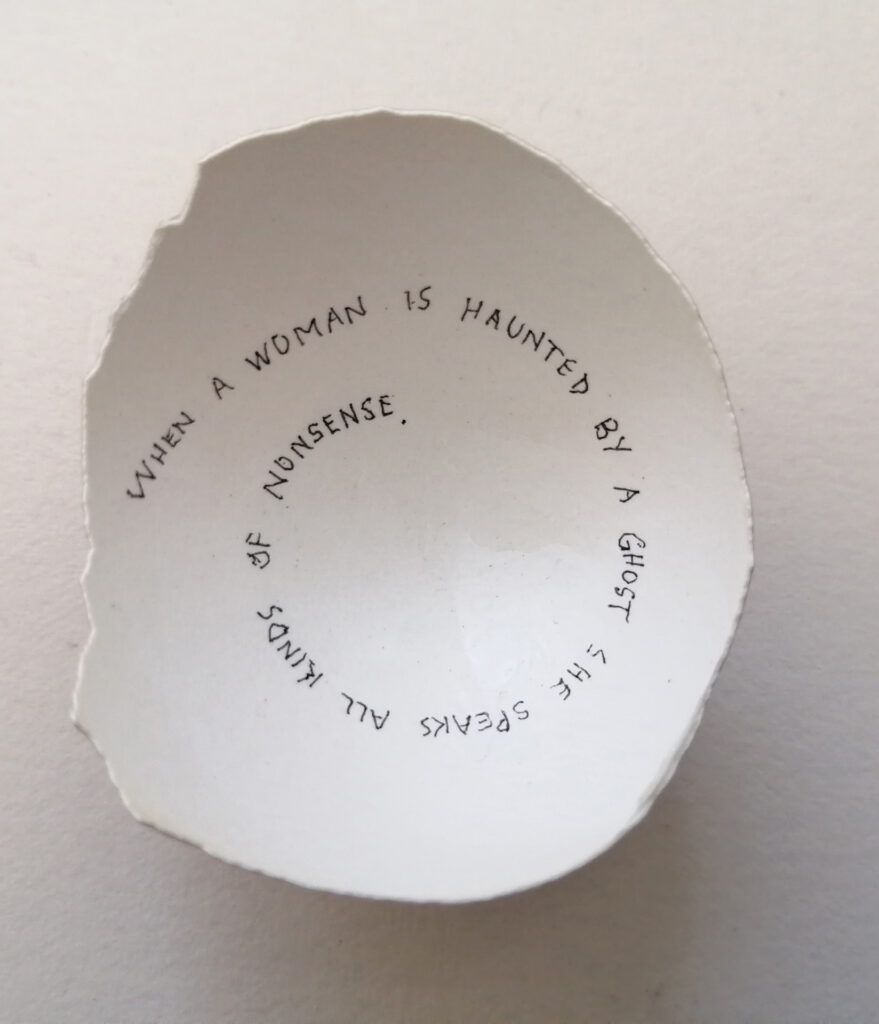

When a woman is haunted by a ghost, she speaks all kinds of nonsense. Similarly, when a person is haunted by noise, she says: “Noise is dead. I am Noise. Why are you searching for Noise? There are so many noises loitering in the street”. People who speak like this are all ghostly haunted, deranged.

Cut-up, origin unknown

White Noise in Eight Amplified Movements (for Clarice Lispector) is an artwork cut-up, a détournement: I transform a short story by agent Lispector into a script for voice, and then into a noise/sonic-poem, further woven into a film score, and finally cast as a mask – where it is put to rest by the final frame, since masks never really rest… just as they are never really worn, they wear us instead (now which of my ghosts said that?).

I thereby cast a life mask instead of a death mask of myself – I was merely playing the mask of many, faking my every death, and all the while quietly stitching… the cosmetic de-and-re-construction of my own vagina – an invagination within the archive called DOMUS. A pocket tribute to the art of dying…

§20 The archive and I

How curious the genre of self-portraiture as it features through the ages in art-making practice, but what should happen if the self-portrait turns to self-appropriation, and in turn to the mask instead of the mirror?

Aren’t all the profiles and compositions (those structuring and framing practices) collected in this archive, in fact masks?

I shall attend to the account of my archival affair with myself – through all the passages to the final work, that emanates from the disguised plot of my dissertation and is appropriately titled An Autopsychography of A Mask. Now if I were to play Derrida pondering his parergon[9]Derrida’s agent of deconstruction in “The Parergon” (1979) that he cites as “neither work (ergon) nor outside work” also serves his discussions around the term “supplement”, to reverse the usual order of priority regarding the relationship between the core and the periphery, to allow the supplement the possibility “to be the core or the centerpiece” (Marder, 2014: 208). I would ask: but where does the mask begin and where does it end when applied to the face, which is no longer a face when masked?

§21 … more of your voice

I AM A TALENTED IDIOT

BLESSED

MAD

I DO NOT KNOW WHAT THE FUCK I AM DOING

OR WHAT THINGS REALLY MEAN

THINGS MAY STARE ME IN THE FACE

FOR AN INORDINATE AMOUNT OF TIME

BUT I FAIL TO SEE THE WOOD FROM THE TREES

I UNDERSTAND NOTHING

AT LEAST I BELIEVE THAT

WHOLE-HEARTEDLY

I ESCAPE THROUGH ART

THE INSTITUTE IS A MACHINE

AND NOT AN ESCAPE MACHINE

I NEED TO FIND MY VOICE

THAT IS A UNIVERSAL NEED

WHATEVER FORM ONE’S VOICE MAY TAKE

NOTHING OTHER THAN A VOICE

“I don’t think that I can listen to more of your voice reciting (slightly reworked) passages from Clarice Lispector’s The Chicken and the Egg [sic.],” said the (ex-) supervisor.

IT HAS ALREADY BEEN WRITTEN

WHICH WILL IT BE?

EITHER

IT IS WRITTEN

OR

IT HAS ALREADY BEEN WRITTEN

NEED TO SPEAK IN CAPITALS

I CANNOT EFFECTIVELY CHANGE THAT

NOW IS THAT MY NATURE?

OR

EVIDENCE

TRACE

OF MY CONDITIONING?

IT IS

AS YOU THINK IT IS

I AM MOST PARANOID ABOUT

BECOMING PARANOID

I should take more notice of these things

As signs

To pursue

Or be pursued

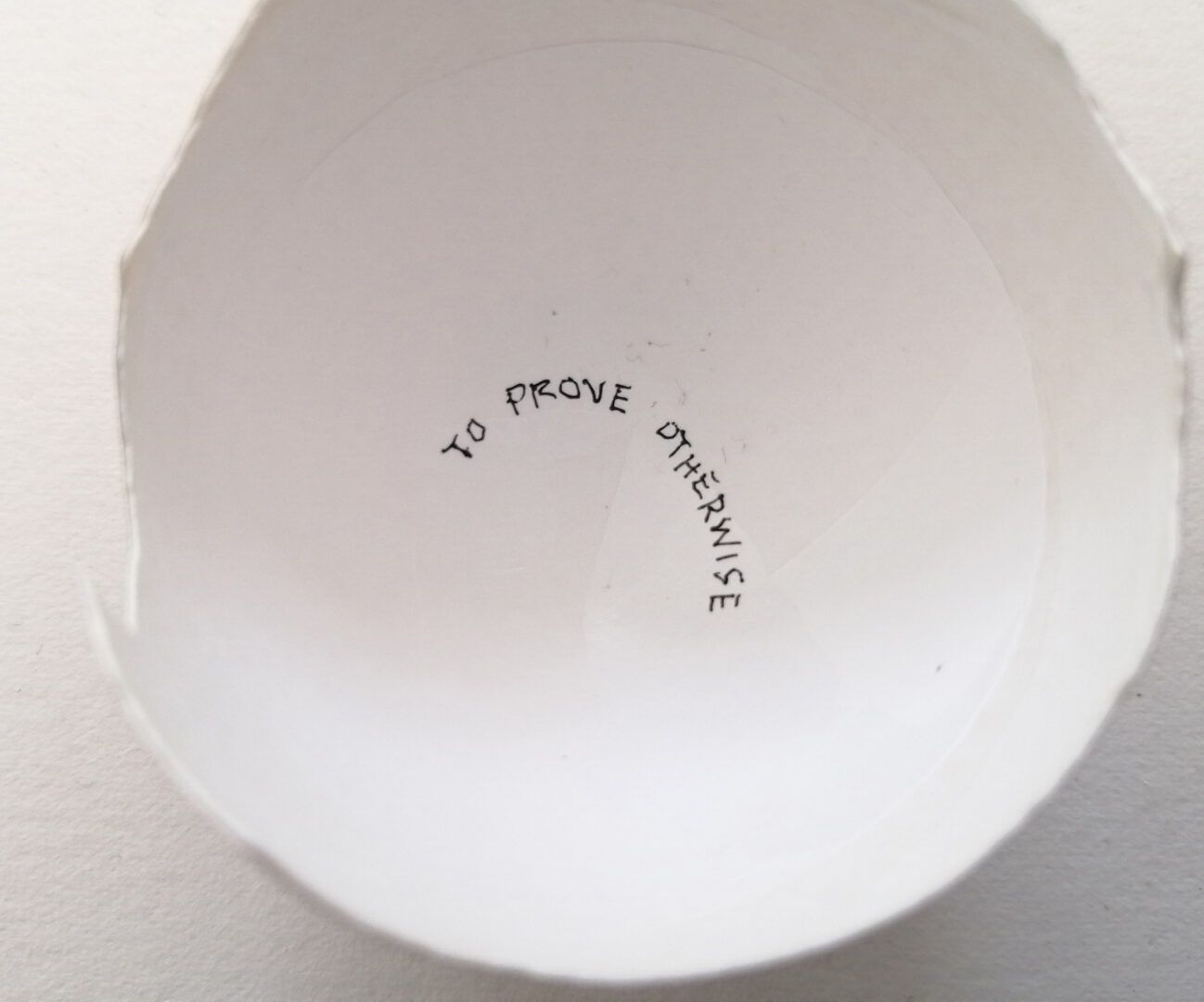

To prove

Otherwise

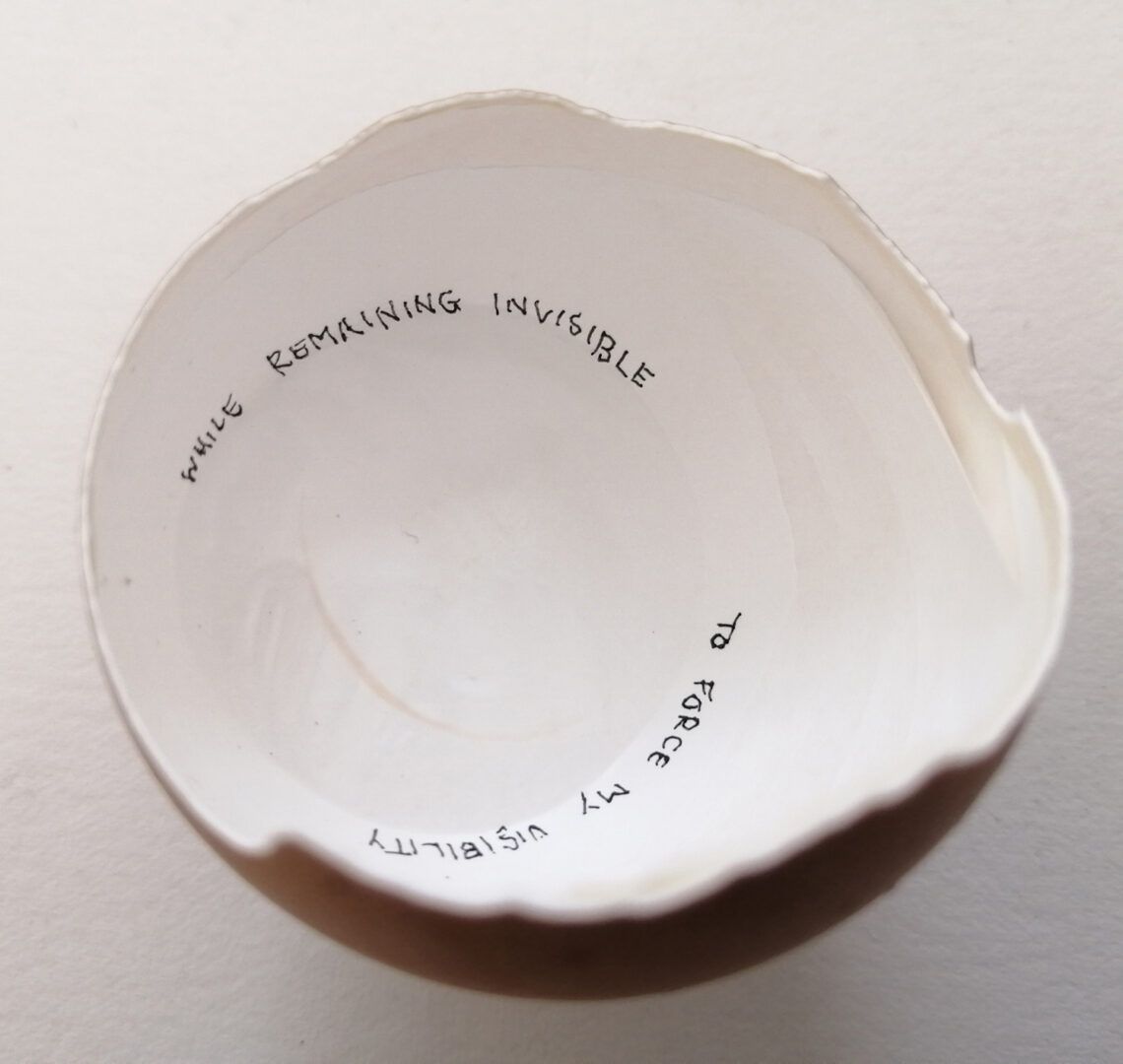

To force my visibility

While remaining invisible

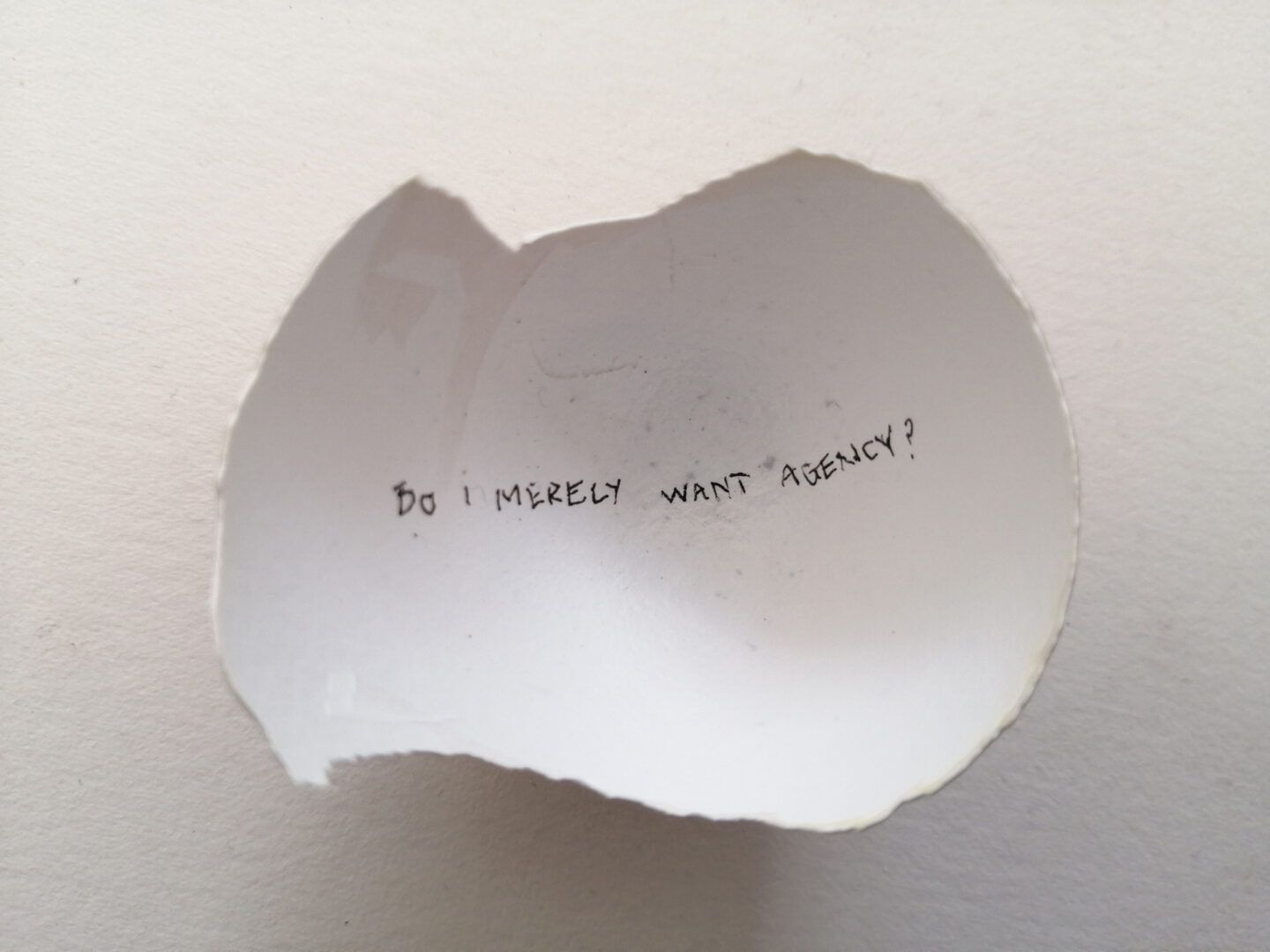

Do I merely want attention?

Do I merely want agency?

Do I merely want love and devotion?

I simply pull the veils repeatedly

Through the slot provided

Provided to confine

The focus

To delimit the territory

That slit box of delicate skins

Was it the sound that mesmerized me?

The feel pull pressure friction resistance surrender

Of that fine tissue

To my pleasure,

my activity, my survival

measures

in meditative movement

my unheimlich maneuvers

That disturbed my mother’s focus

And unsettled her

To recognize the unsettled before her

But not register the umbilicus of discord

That unheimlich phase of our immigration

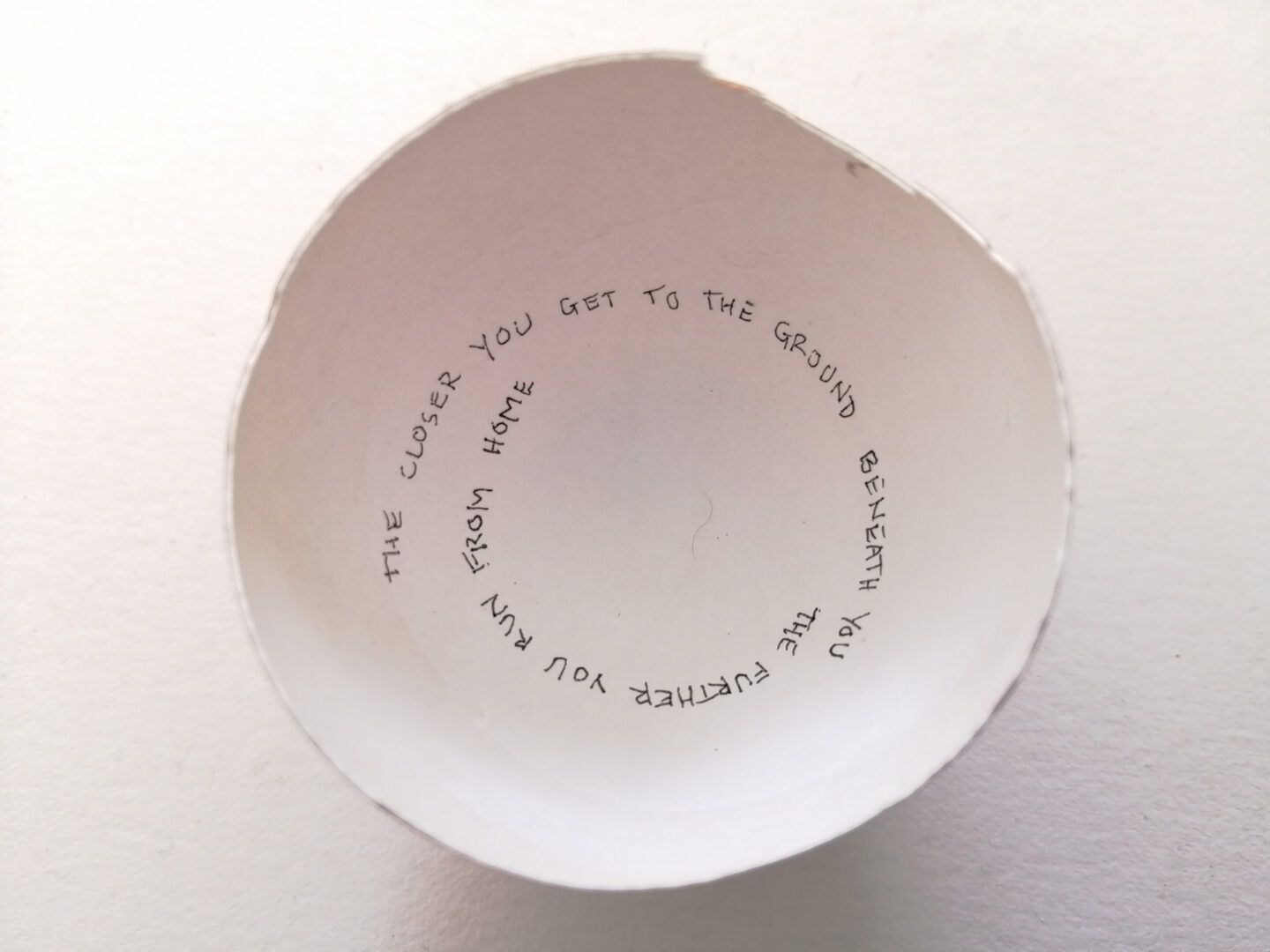

The closer you get to the ground beneath you

the further you run from home

I zone out perhaps,

or do I zone in?

Part of my curse

In seeing things in such a close way…

The closer you inspect the rabbit hole

The further you fall into the abyss

Of the looking glass

And the mask

An affair of a different sort

“Everything that menstruates is an actress”

Morphs to…

“Everything that menstruates is a mask”

The mask of the moon

The vanishing Cheshire cat

This pHd

needs to be:

A box of shell membranes;

The parts I discarded

My eggshells must now become a comment on:

After…

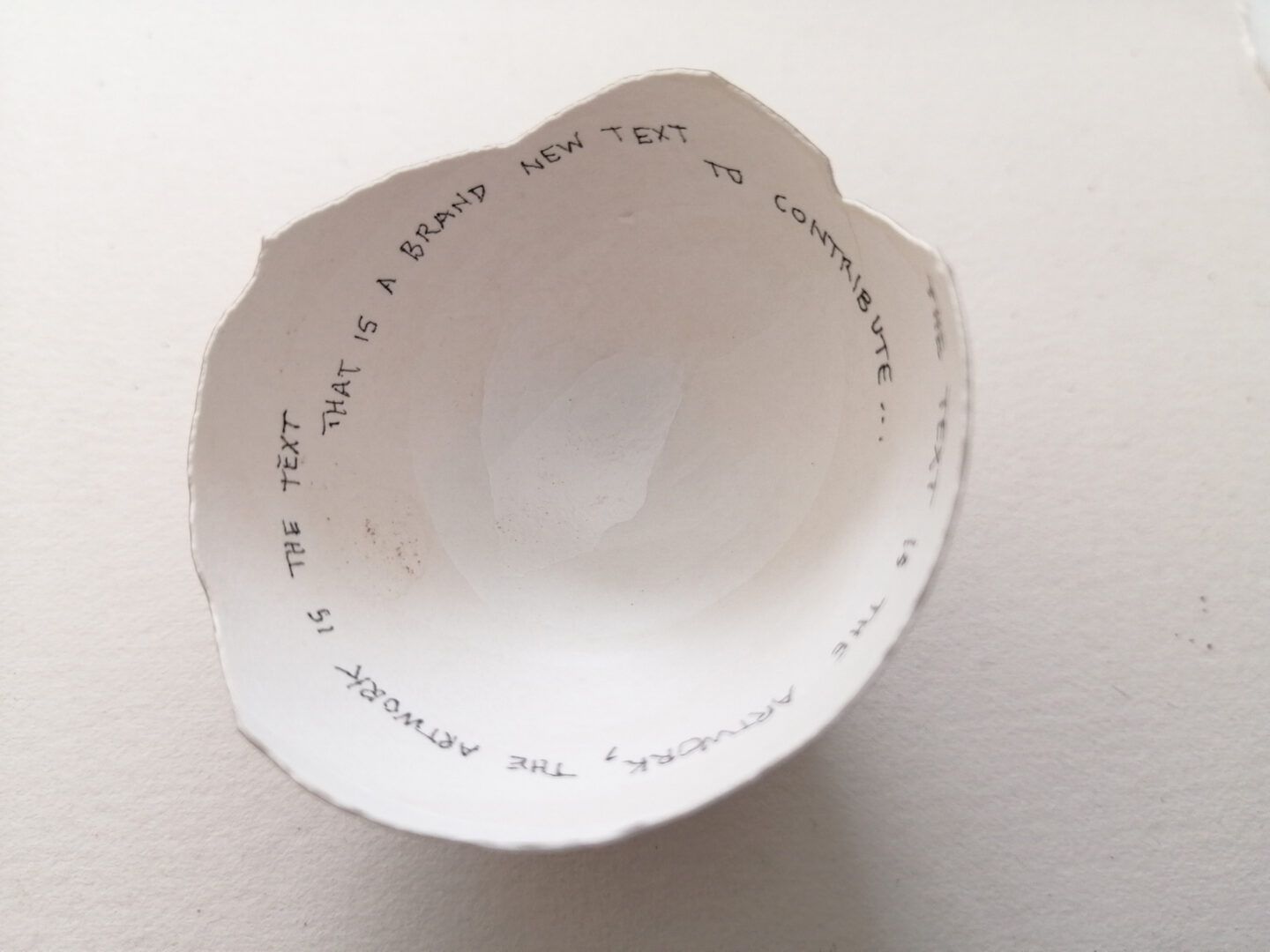

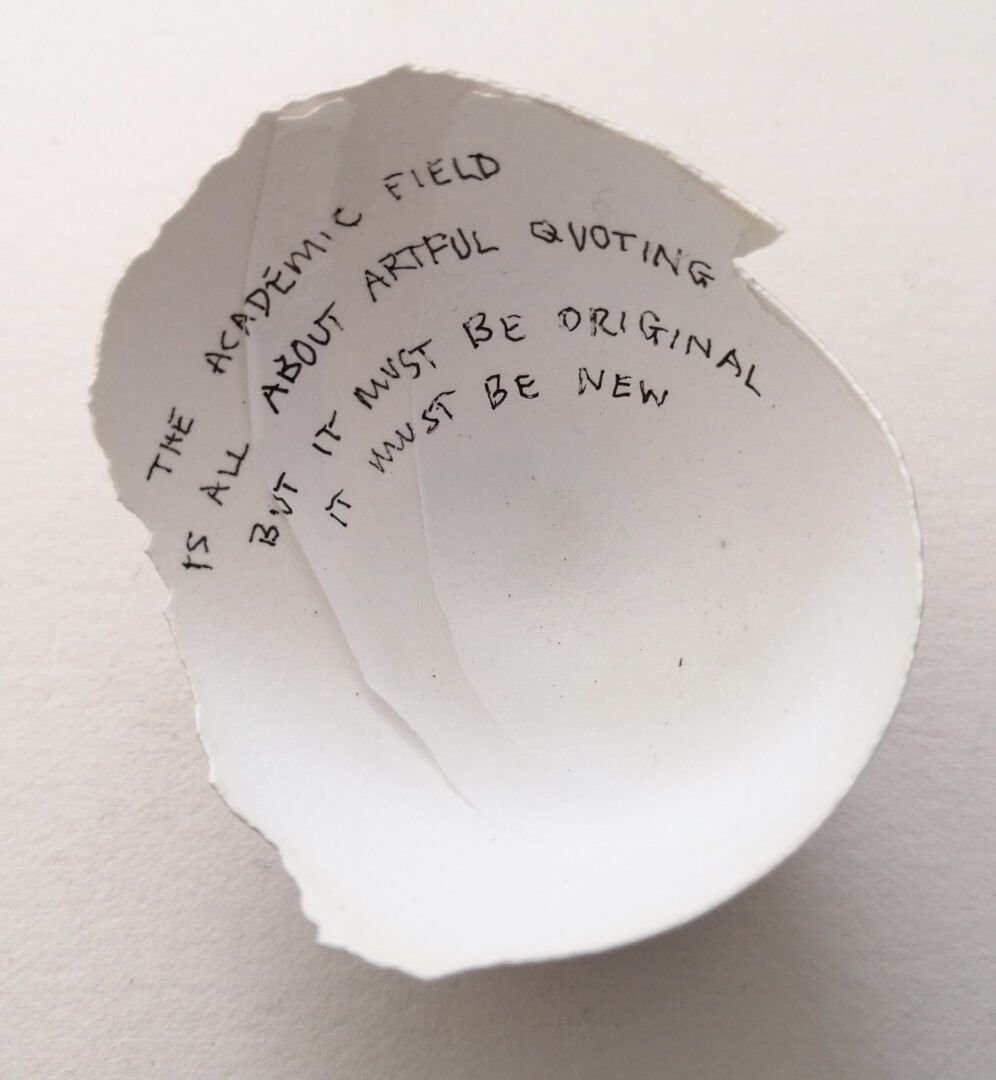

The academic field is all about artful quoting

But it must be original

It must be new

I have to argue

the project is the practice,

the artwork is the thesis,

the dissertation simply

an exegesis

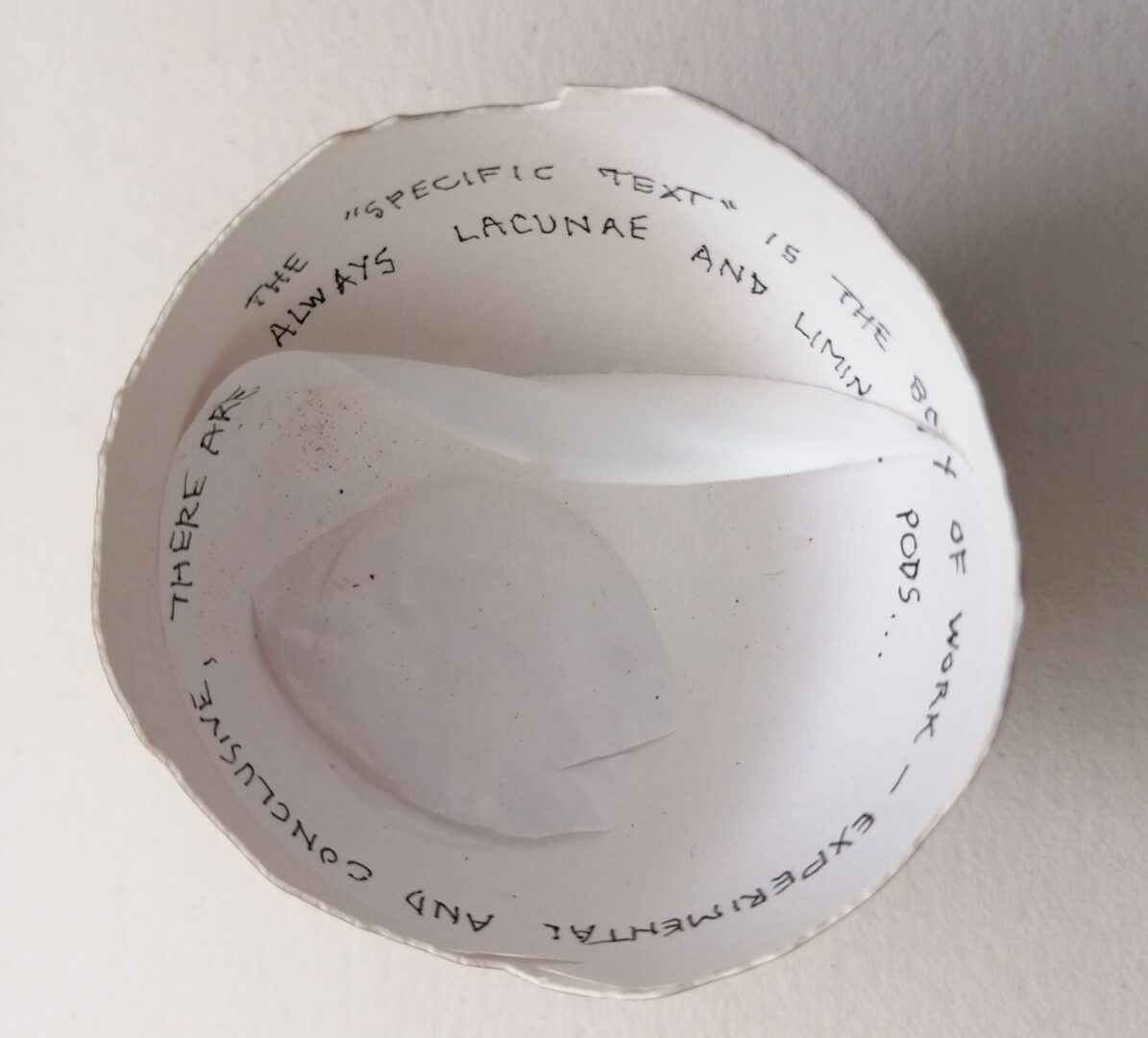

The “specific text”

is the body of work –

experimental and inconclusive,

there are always lacunae, and liminal pods

The text is the artwork,

the artwork is the text.

That is a brand new text

to contribute

The body of work in research through practice

is the text that is the object of analysis,

which is in fact a subjective interpretation

since I am also the maker of the work

the creator and interpreter of visual and material texts

(and textilities)

I create the beast with entrails

and then perform the sacrifice

upon it

Iphigenia must be sacrificed

by her father’s own hand

in order to channel the divine message

tracing life & death forces

of the innards on display

as translated by the haruspex

Bataille talks a lot about such fascinating things

and I in turn, become the divinatory madwoman

or is it mad mxn?

How may I emulate my lords & masters?

Their tools are no longer of use,

Audre Lorde noticed as much.

§22 Whiteness is a mask

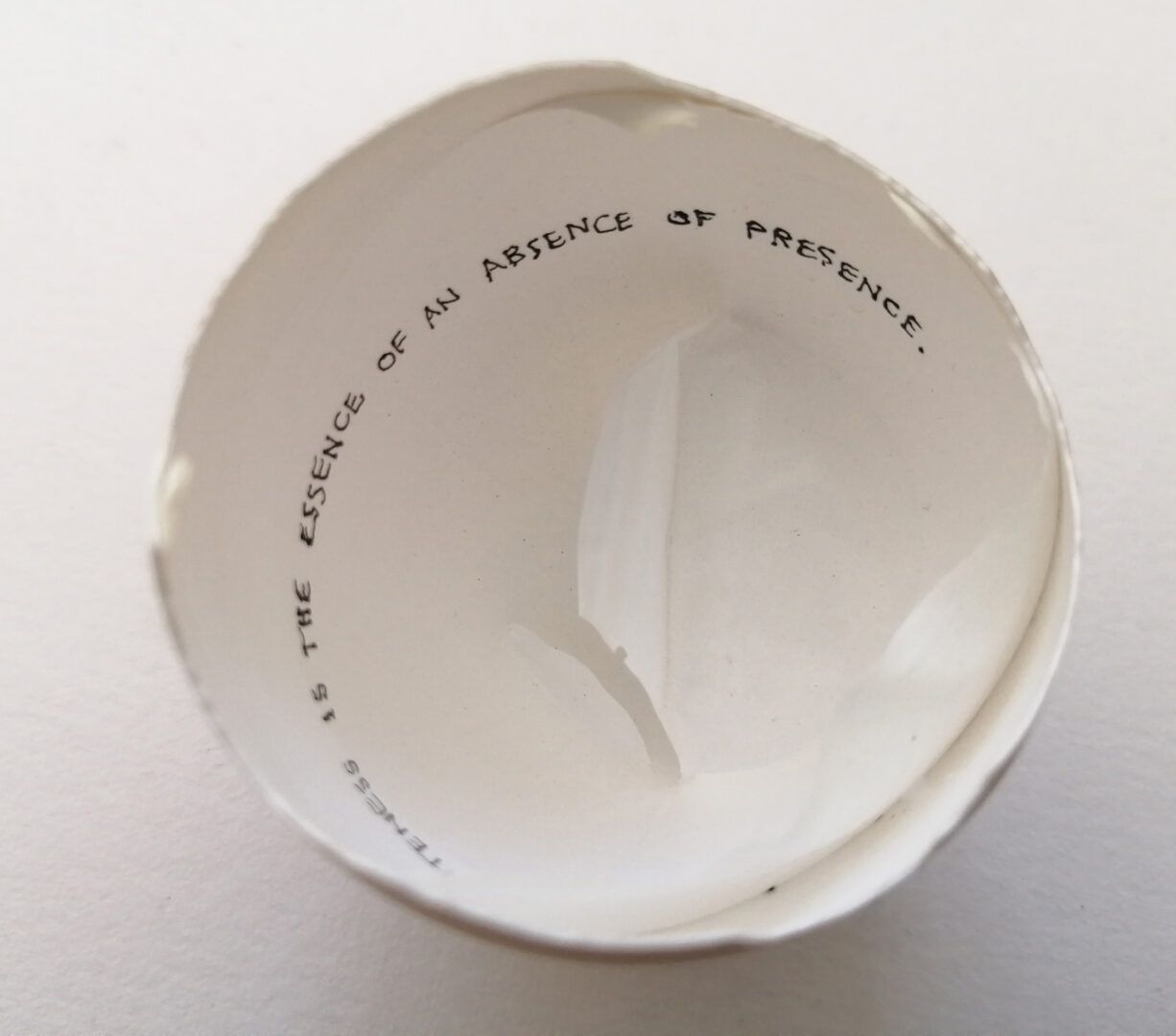

The autopsychography of a mask is a decolonised hauntology of whiteness in the DOMUS, an invaginated pocket of psychographic material and analysis of an identity that was never there.

Whiteness is the essence of an absence of presence.

§23 the embodied sonic

i am carving out a niche for myself, quite frankly,

i read and write the archive how i like…

White skin, Wrong masks…

i speak in “…”

i suggest everything by nothing

i suggest nothing voluntarily

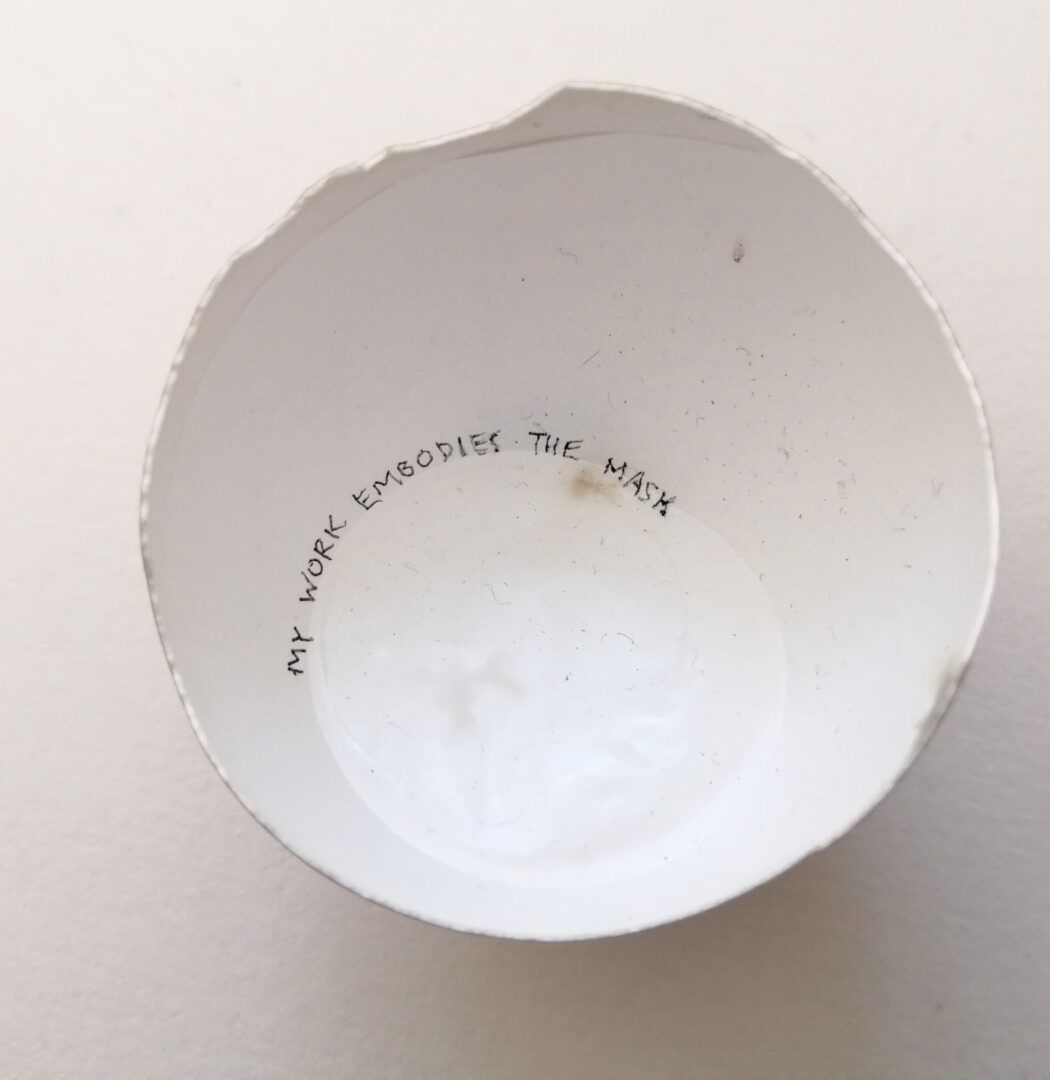

my work embodies the mask

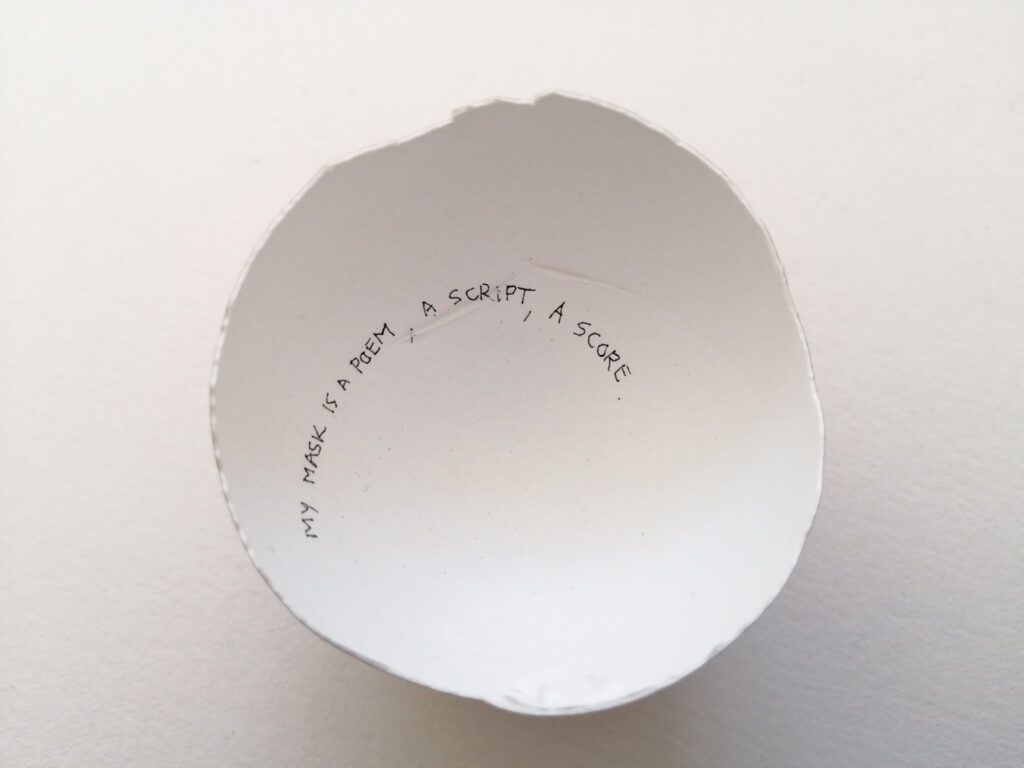

my mask is a poem, a script, a score.

everything we know now is cut from another part

cut to and from another past

another now returns

sutured

disfigured

and comfortably numb

how Pink Floyd churned my stomach

as did Dire Straits

time is indeed out of joint

from Shakespeare to Derrida…

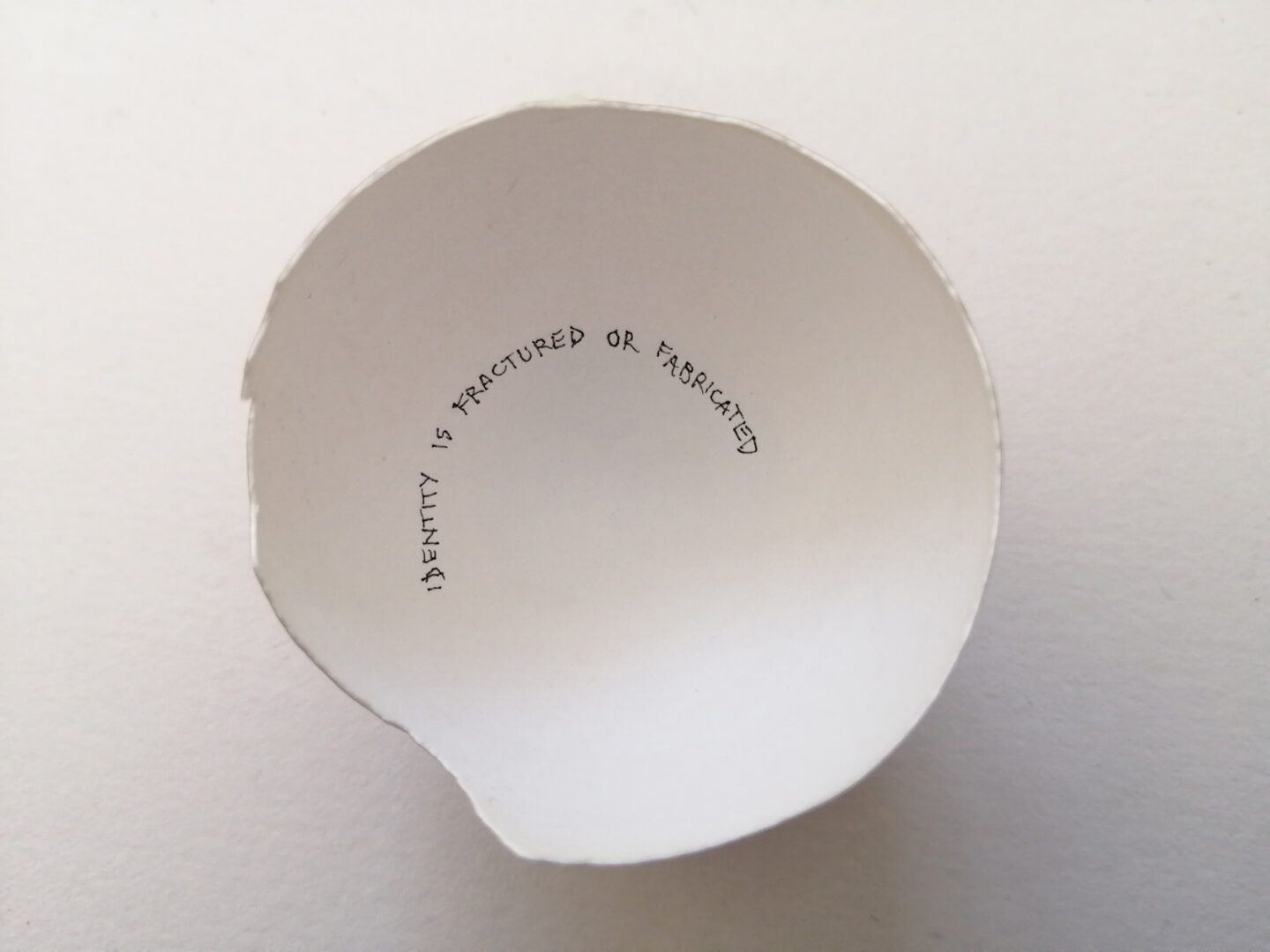

identity is fractured or fabricated

masked or mimed

sutured

seamless

eyes without…

no mouth but I must

scream for Beckett

or after

Beckett instead?

my score/script/poem is a mask

Our sonic memories are clearly outlined – one can recall them, invoke them, by simply surfing time and the net. I may swiftly bind my recollected memory with an embodied one while listening to a YouTube replay of “Money for Nothing” (1985) – and my stomach will not lie. What was it that discomfited me so viscerally, and alienated me from that sound? Simply my parents’ incessant replay of that particular LP from their music collection?

A particular generation’s form of popular culture as distinct from my own childish sense of what good music should or should not sound like? Or did the TV/radio stations overplay it to the point of assaulting my sonic pleasures and taste? Just what churns my stomach exactly? Is it purely associations – taken root from back then? Or rather the associations formed across time, in my reflections towards the past? Can hauntological practices, particularly sonic hauntologies, address this misalignment of time past and time present adequately? Mark Fisher seemed to think so, and following his thesis around the “Metaphysics of Crackle” (2013), time is indeed out of joint.

§24 the heart of tradition

A folk song picked up from “an old ploughman” by Scottish traditional singer, Belle Stewart who added the first verse, and passed it on to her daughter Sheila Stewart who included it in her album From the Heart of the Tradition (Topic Records: 2000) under its other title “Blue Bleezing Blind Drunk“. It was first recorded on the musical family’s album The Stewarts of Blair, Lismor, 1985. Linda Thompson sang an extended version of the song – she wrote the fourth verse – and included it on her album Won’t be Long Now, Topic Records, 2013. I must have first heard this song on my return visit to Scotland, around the age of five, in the context of the “sing-song” ritual that my father’s family performed in celebratory reunion mode – each family member participated in the inebriated song circle with one or two songs for which they had become renowned. My aunt would sing this in a sweet but maudlin tone whenever she was called upon to “gie us a song”.

§25 Elisabeth stitching… memoirs of a ghost

My oldest, dearest memory of defeat – admittedly coloured and shaped by those with an objective top view, namely my parents – has to be of the day I lost Elisabeth.

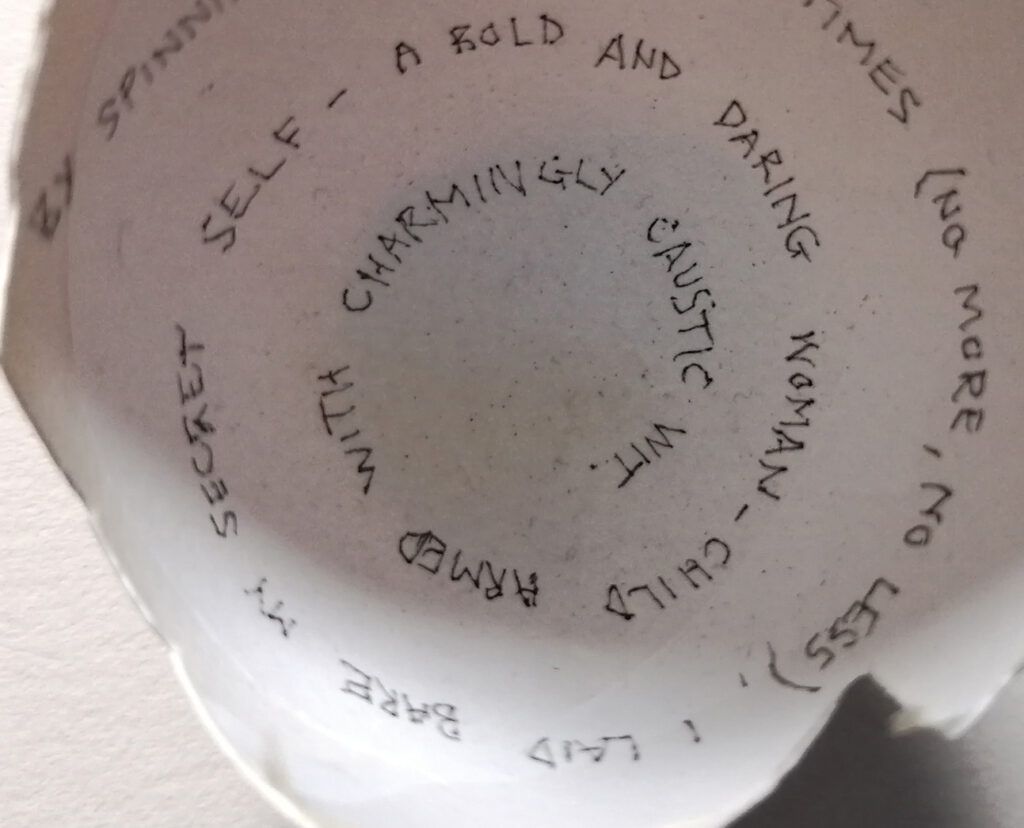

At the tender age of around five, I discovered my brother’s nemesis, and therefore the key to foiling all males already featured in or about to enter my sphere. By spinning around five times (no more, no less), I laid bare my secret self – a bold and daring woman-child armed with charmingly caustic wit. A performance by which I declared, ridiculed, and ordered in queenly fashion – for sheer entertainment’s sake – displaying a parodied self with the power to simultaneously parody the witnesses.

Not all were charmed, the empress-types, for instance, found me obnoxious, cheeky, and a likely candidate for borderline personality disorder. But the worst case of analysis came from matron Deane – she called for a priestly intervention, an exorcism.

My parents’ protestations and defence of my “creative imagination” did not deter matron D’s sense of responsibility to declare the law and order, once and for all. Matron D simply bided her time till we were alone together. I vaguely recall her ordering me to bring Elisabeth out and to put her away again, along with her intimations that Elisabeth was in fact no longer welcome to entertain the king and his merry men with her coquettish ways.

But now my poor image memory dissolves into dream vision: we walk out into the garden and identify a tree, matron D announces that Elisabeth is in fact hiding in the tree since she was banished from the main house, and then suddenly matron D extends her arm as a rifle: “Bang, bang! Elisabeth is now dead!” I look up at her mime-shoot performance and then up at the tree, and that is where the memory ends with a sharp cut.

To my dream of being shot in the back of the head by a faceless hijacker whereby I experience (my imagined sense of) dying. At the approximate age of fourteen – violent hijacking stories circulated widely and contributed to the general propaganda-phobia running up to the general elections of 1994, South Africa. The most memorable aspect of this dream is its layered sensation: the pressure in the weight of the striking lead starkly contrasted with its follow-on – that thick membranic void enveloping my head, as if it were floating in mercury (or was it in fact amnion? Memory is always prey to interference) – followed further by the ecstatic sense of falling in slow motion. In that incongruous sensational state – a free-floating bliss without end – I sensed the infinity of what some people refer to as heaven, that zone of the afterlife.

§26 From my library

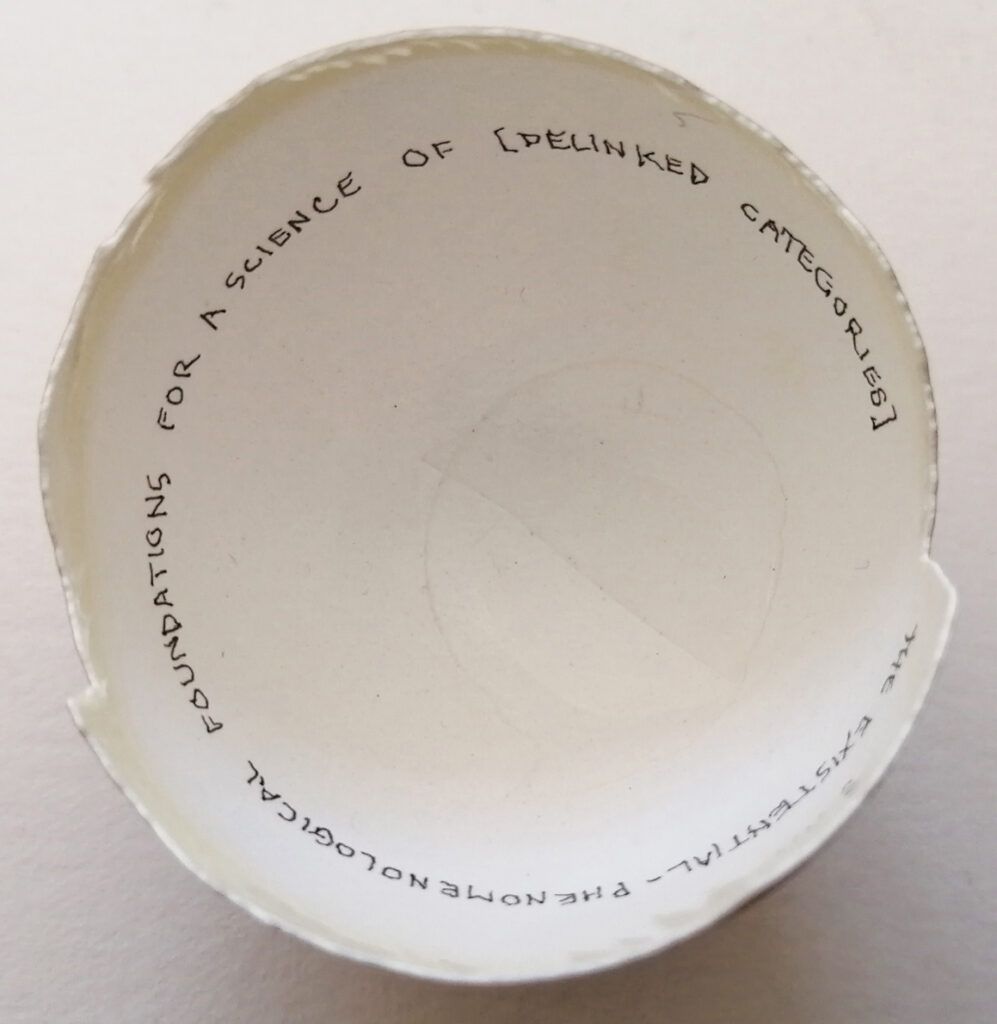

The existential-phenomenological foundations for a science of [de-linked categories]

The term de-linked refers to an individual category the totality of whose experience is split in two main ways: in the first place, there is a rent in her relation with her archive and, in the second, there is a disruption of her relationship with her own category. Such a category is not able to experience herself “together with” other categories or “at home in” the archive, but, on the contrary, she experiences herself in despairing aloneness and isolation; moreover, she does not experience herself as a complete category but rather as “split” in various ways, perhaps as a mind more or less tenuously linked to a body without organs, as two or more shelves, and so on.

Détourned quote from R.D. Laing, The Divided Self (1965: 17)[10] Original quote by R.D. Laing: The existential-phenomenological foundations for a science of persons. The term schizoid refers to an individual the totality of whose experience is split in two main ways: in the first place, there is a rent in his relation with his world and, in the second, there is a disruption of his relation with himself. Such a person is not able to experience himself “together with” others or “at home in” the world, but, on the contrary, he experiences himself in despairing aloneness and isolation; moreover, he does not experience himself as a complete person but rather as “split” in various ways, perhaps as a mind more or less tenuously linked to a body, as two or more selves, and so on.

Art & Education. 2012. Announcement: Memories Can’t Wait [Symposium: December 14-15, 2012 at International Center of Photography, New York]. Available: [2020, November 25].

Barthes, R. 1977. Roland Barthes by Roland Barthes. (Trans.) R. Howard. Berkley, Los Angeles: University of California Press.

Bartkowski, F. 1980. Feminism and Deconstruction: “A Union Forever Deferred”. In Enclitic Vol. 4:2 (Fall), pp. 70-7.

Bloom, H. 1973. The Anxiety of Influence: A Theory of Poetry. New York: Oxford University Press.

Burton, A. (Ed.). 2005. Archive Stories: Facts, Fictions, and Writing of History. Durham & London: Duke University Press.

Deane, N. 2012. A Heritage of Secrets: In Confessional Mode. Unpublished MFA Dissertation, Cape Town: University of Cape Town.

Deane, N. 2020. A very sad story. [MP4]. South Africa.

Derrida, J. 1973. Speech and Phenomena and Other Essays on Husserl’s Theory of Signs. (Trans.) David B. Allison. Evanston: Northwestern University Press.

Derrida, J. & (trans.) Owens, C. 1979. The Parergon. In October,Vol. 9 (Summer): 3-41. Available:[16 October 2017].

Dire Straits, 1985, ‘Money for Nothing’, Brothers in Arms, Album, UK: Vertigo & US: Warner Bros.

DOMUS (Documentation Centre for Music), Stellenbosch University. Available: [2018, May 7].

Du Bois, W.E.B. 1903. The Souls of Black Folk. Chicago: A.C. McClurg & Co.

Evans-Wentz, W. 1927. The Tibetan Book of the Dead. London: Oxford University Press.

Fisher, M. 2013. The Metaphysics of Crackle: Afrofuturism and Hauntology. In Dancecult: Journal of Electronic Dance Music Culture 5(2): 42-55.

Gates-Stuart, E. and Wolmark, J. 2004. Cultural Hybrids, Post-disciplinary Digital Practices and New Research Frameworks: Testing the Limits. [Online]. Available: [2016, April 20].

Gilliland, A. J. and Caswell, M. 2016. Records and their Imaginaries: Imagining the Impossible, Making Possible the Imagined. In Archival Science, 16 (1), March: 53-75. UCLA Previously published works. [Online]. Available: [2016, May 10].

Gurevich, M. 2014. ‘Woman is still a woman’, Let’s Part in Style, Album, Michelle Gurevich & Van Roland, Berlin.

Hawke, M. & Kwok, P. 1987. A Mini-Atlas of Ear-drum Pathology. In Can Fam Physician Vol. 33: 1501 – 1507 (June).

Holly, M. A. and Smith, M (eds.). 2008. What is research in the Visual Arts? Obsession, Archive, Encounter. Williamstown, Massachusetts: Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute.

hooks, b. 1996. Real to Reel: Race, Sex, and Class at the Movies. London & New York: Routledge.

Kaganof, A. & Deane, N. 2002. Primal Scene [Video]. Aryan Kaganof collection. Documentation Centre for Music (DOMUS), Stellenbosch University.

Ketelaar, E. 2001. Tacit Narratives: The Meanings of Archives. In Archival Science 1: 131-141. Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Laing, R. D. 1965. The Divided Self: An Existential Study in Sanity and Madness. London: Penguin Books.

Licht, A. 2007. Sound Art: Beyond Music, Between Categories. New York: Rizzoli International Publications.

L’Internationale Online: Aikens, N., Çaka, B., Franssen, D., Haq, N., López, S., Paynter, N., Petrešin-Bachelez, N., Pinteño, A. Prieto del Campo, C., Thije, S., & Železnik, A. (editorial board). 2015. Decolonising Museums. [Online]. Available: [2016, April 7].

L’Internationale Online (editorial board) and Ištok, R (eds.). 2016. Decolonising Archives. [Online]. Available: [2016, April 7].

Lispector, C. 1992 (Portugese: 1964). The Egg and the Chicken. In The Foreign Legion: Stories and Chronicles. New York: New Directions.

Lispector, C. 2012. Água Viva (1973). (Trans.) Stefan Tobler. New York: New Directions Publishing Corporation.

Lyotard, J. 1993. Libidinal Economy. (Trans.) Grant, I.H. Bloomington & Indianapolis: Indiana University Press.

Marder, M. 2014. The Philosopher’s Plant: An Intellectual Herbarium. New York: Columbia University Press.

MacKenny, V. 2002. Angry letters on “lewd” art performance give rise to NSA Forum. In artthrob (Archive: Issue 61, September) [Online]. Available: [2020, March 3].

Mainly Norfolk: English Folk and Other Good Music. ‘Blue Bleezin’ Blind Drunk’/’Mickey’s Warning’. Available: [2020, August 14].

Mbembe, A. 2002. The power of the archive and its limits. In Refiguring the Archive, edited by C. Hamilton, V. Harris, J. Taylor, M. Pickover, G. Reid, and R, Saleh. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic, pp. 19-28.

Merriam-Webster Dictionary. (n.d.). S.v. ‘decentering’ [Online]. Available: [2020, October 8].

Mignolo, W. & Tlostanova, M. 2006. Theorizing from the Borders: Shifting to Geo- and Body-Politics of Knowledge. In European Journal of Social Theory, 9 (2): 205—21.

Mignolo, W. D. 2007. Delinking. In Cultural Studies, 21: 2, 449 – 514.

Mignolo, W. D. 2011. The Darker Side of Western Modernity: Global Futures, Decolonial Options. Durham: Duke UP.

Mignolo, W. D. and Vázquez, R. 2013. Decolonial AestheSis: Colonial Wounds/Decolonial Healings. In Social Text/Periscope. [Online]. Available: [2016, May 23].

Mignolo, W.D. 2017. Interview – Walter Mignolo/Part 2: Key Concepts [Interview], in E-International Relations by Alvina Hoffmann, 21 January 2017. Available: interview-walter-mignolopart-2-key-concepts/ [2020 August 10].

Minh-ha, T.T. 1992. Framer Framed. New York & London: Routledge.

Minh-ha, T. T. 1998. Shifting the Borders of the Other: An Interview with Trinh T. Minh-ha [Interview], in Telepolis by M. Grzinic, 12 August 1998. Available: [2020, October 7].

Piepenbring, D. 2014. It Changes Nothing. In The Paris Review [Online]. Available: [2019, September 11].

Quijano, A. 2007. Coloniality and Modernity/Rationality. In Cultural Studies 21(2-3): 168-78.

Schwarzkogler, R. 1965-69. Selected Scores for Unperformed Aktions. [Online]. In Supervert: Electronic Library. Available: [2020, October 8].

Spieker, S. 2008. The Big Archive: Art from Bureaucracy. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Mit Press.

Stewart, S. 2000. ‘Blue Bleezing Blind Drunk’, From the Heart of the Tradition, Album, Topic Records, UK. Available: [2019, January 15].

Thompson, L. 2013. ‘Blue Bleezin’ Blind Drunk’, Won’t be Long Now, Album, Topic Records, UK. Available: [2020, August 16].

Wa Thiong’o, N. 1986. Decolonising the Mind: the Politics of Language in African Literature. London: James Currey; Portsmouth, N.H.: Heinemann.

| 1. | ↑ | DOMUS: Documentation Centre for Music, University of Stellenbosch. |

| 2. | ↑ | Willem Boshoff |

| 3. | ↑ | In fact it’s a neither-nor-conciousness |

| 4. | ↑ | In fact alien to homeland too, but not via the skin |

| 5. | ↑ | “We can read the term ‘inappropriate/d other’ in both ways, as someone whom you cannot appropriate, and as someone who is inappropriate. Not quite other, not quite the same” (Interview: Trinh T. Minh-Ha, 1998). |

| 6. | ↑ | “Fragmentation and discontinuity, then, comprise a tool that these artists use to allow for polyphonic narrative structures” – J.K. Odin (1997: Online). |

| 7. | ↑ | Based on Rudolf Schwarzkogler’s Selected Scores for Unperformed Aktions (1965-69). from my archive (2011): typewritten text and bone prints on Fabriano cotton paper. |

| 8. | ↑ | Song title from Fear of Music album by Talking Heads (1979), also the title of the Symposium held in 2012 at International Center of Photography, New York that sought to investigate various artistic strategies “to rethink ways to produce, document, and archive forgotten, ambiguous, traumatic, or marginalized memories.” Available: [2020, August 25]. |

| 9. | ↑ | Derrida’s agent of deconstruction in “The Parergon” (1979) that he cites as “neither work (ergon) nor outside work” also serves his discussions around the term “supplement”, to reverse the usual order of priority regarding the relationship between the core and the periphery, to allow the supplement the possibility “to be the core or the centerpiece” (Marder, 2014: 208). |

| 10. | ↑ | Original quote by R.D. Laing: The existential-phenomenological foundations for a science of persons. The term schizoid refers to an individual the totality of whose experience is split in two main ways: in the first place, there is a rent in his relation with his world and, in the second, there is a disruption of his relation with himself. Such a person is not able to experience himself “together with” others or “at home in” the world, but, on the contrary, he experiences himself in despairing aloneness and isolation; moreover, he does not experience himself as a complete person but rather as “split” in various ways, perhaps as a mind more or less tenuously linked to a body, as two or more selves, and so on. |