MBALI KGAME

Mphutlane wa Bofelo's Transitions: from Post-Colonial Illusions to Decoloniality What went wrong and what now?

Between the flashing green and the flashing red light, a presence so mighty and enchanting, cannot be missed. Miseka Gaqa, in a long black dress and a statement isikhakha black and white doek of the AmaXhosa nation. Her fine tuned soprano voice effortlessly piercing through the bass, the trumpet horns, the drums and the keyboard. She sings, sikhalela umhlaba wethu (we are crying for our land) umhlaba wethu (our land), closer and more attentively listen to the message, you hear, a cry that vibrates and echoes from decades ago.

It is the year 2018, the band Iphupho L’ka Biko is rendering a coaxing song that houses a nation’s cry from the very ground where its original composers have been laid to rest. This moment becomes a soundtrack accompanying the passages of text in this book under review.

Published in 2019 by Ditiro media, Transitions: From Post-colonial Illusions to Decoloniality is by South African essayist, poet, cultural worker and social critic, Mphutlane wa Bofelo, who takes on the role of a community member with the gift of hearing whispers from a realm beyond reach. Sent to awaken, educate and inform the community about the journey they’ve walked, how they’ve walked that journey and why they continue to cry at a time when their tears were supposed to be long wiped out with gold tissues. Reading the book brings an image of the community member standing on a stump where a sunland baobab tree once firmly stood and is committed to evoking a fire that will help the community see clearly and journey on, reclaiming what they’ve lost. In the text, Mphutlane employs dynamic voices, philosophy, theory and activist scholars from the broader black school of thought as his accomplices in order to point out post-colonial illusions and the road to conversations and acts around the subject of decoloniality.

Mphutlane has assembled five remarkable and lengthy essays offering deep critique on the experiences in and the current state of “post-apartheid” South Africa. Where black people have been let down. Where the earth is crumbling underneath them. Most importantly, the heart of the book houses the idea of decoloniality as the key to unlocking the brutality of the cycles we have been locked into due to the common odds that have been against us from apartheid to “post-apartheid”. In between a thorough incorporation of theory that accompanies the criticality of these essays, Mphutlane, weaves in his own poetry and those of others. This weaving serves not only as interlude but also amplifies and supports the arguments and analysis that the essays unveil.

The first essay Memory and Being opens with a set of questions, probing different ideas of who black people are outside of what white power and what white supremacy has moulded as our reality and identification of self (as agency) and as a collective. How far back can we dig in our memories (recorded and archived history) to find an identity and way(s) of life, of being, that are not linked to white influence or colonial impositions. Mphutlane uses Africana Philosophy to propose that “formerly enslaved, colonised, oppressed and exploited cannot take control of their lives and shape their own destiny without critically interrogating, re-membering, de-constructing and reconstructing their past”.

In this essay, Mphutlane is committed to honouring the importance of historical consciousness as an important concept towards embarking on a liberation project that has a clearer understanding of the position, identification, and realisation of black people’s current state. Mphutlane critically challenges the “born free” phenomenon where according to him “black youth are assailed with the social rhetoric that urges them not to make reference to the apartheid past or its impact on their social realities”. Here, the youth is romanticized as a generation that is born into freedom therefore, theirs is ostensibly a life filled with possibilities without limitation.

Applying the importance of historical consciousness, Mphutlane notes “This kind of mindset ignores the peculiar circumstances of black youth who are victims of intergenerational poverty, structural poverty and structural unemployment accrued from an economy characterized by disarticulation, enclave and the intersection between racial, class and gender inequalities”. This essay on memory and being digs deeper into the challenges faced by young people. Those who occupy the street corners.

Those who have fallen into drugs and other substances as an escape from the pressures pinned on them within their community and society at large. Those who also find themselves in institutions but fall victim to being fed an education that strips them of their humanity.

In the second essay The Songs of Solomon Mphutlane maps out, in detail, the activities that have been at play in reconstructing history and memory of black people to disempower them. From laws that have protected and endorsed white power from apartheid to post-apartheid South Africa. To different tools such as the media’s selling images, religion, and what education feeds the mind. Thus, subconsciously, tinting the memory of black people as inferior and uncivilised in order to continue oppressing them. Mphutlane substantiates the significance of the Black Consciousness perspective for “black people to interrogate their pre-colonial and colonial past and to critically examine the continuities and discontinuities of past conditions and traditions in the present and take their own decisions on what to discard and what to carry into the future”.

Here, the approach becomes that black people must define and name themselves out of their own interpretations of their historical material, cultural, political, social and economic experiences in order to humanise and empower themselves.

In the essay Post-Apartheid or Neo-Apartheid? Mphutlane argues that even though there is the absence of patrolling police vans in the township and no obvious obligation that compels black people to carry identity documents as a marker of their existence in the country, the word ‘democracy’ masks new-age apartheid because even with the transitions, not much has actually changed.

This essay floats this argument through the reflections of young black South African poets who have lived through the tail-end of apartheid and have experienced “post-apartheid” South Africa first hand. Each of the eight poets interviewed by Mphutlane offers their opinion and their memory of the transition and how that has influenced the making of their art. In the following essay Being Black Twice Mputlane uses a similar approach where he brings in other voices to speak about their memory of apartheid and trace the steps they have walked in the supposedly new South Africa. This essay explores the historical consciousness of young black working women from different disciplines and the challenges they face in the workplace where a black woman’s labour contribution is not compensated accordingly. Mphutlane explains that, “In the South African context, capitalist division of labour highly utilizes prevailing structures of racial segregation and patriarchy”. In this case black women suffer oppression twice, first for being black and second, for being women. Apart from being confronted with religious, cultural and political struggles of policing women’s bodies, the women in conversation with Mphutlane in this chapter have another commonality as they recollect their experiences, that these realities do not begin with them, they date back to when their mothers were working women under apartheid. This, a clear illustration that little, if anything has changed. The continuities are glaringly evident, obvious and everywhere to be seen, felt and lived (by black people).

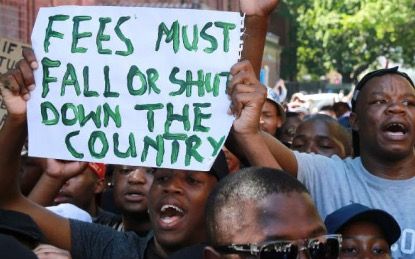

The last essay Fallism and the dialectics of spontaneity and organization is the driving motor of the entire book. It ties together the arguments brought forward in the first four essays. In text-based illustrations, it proves that South African as a democratic dispensation is an illusion. It does this through paying homage to the principles and ideologies embedded in the Fallism movement in relation to the discourse of transformation in South Africa. This essay argues how the theme of decoloniality and transformation has been more pronounced in South African public discourse subsequent to and because of the Fallism movement. The essay also shows how the continuities between apartheid and “post/neo-apartheid” realities shape the political consciousness, ideological perspective and activism of the Fallism generation.

Mphutlane discusses “the practical reality of the connection between the social structures that oppress, exploit, de-humanise and discriminate against Black people, women, the gay, lesbian, bi-sexual, transgender and intersex (GLBTI) community, workers and disabled people raised awareness of the interconnection between racism, capitalism, patriarchy, homophobia, ableism etc”.

He goes on to add, “What began as a call for the removal of the statue of Cecil John Rhodes at the University of Cape Town and the fight against fee increases at Universities birthed the exposure of the failure of the country to deal with issues of redress, restitution, restoration, reparation, redistribution and reconstruction as necessary prerequisites for genuine reconciliation and sustainable nation building”.

In closing, the essay faithfully records the Fallism movement as a movement that has brought radical awakening and change in post-1994 South Africa. Mphutlane also unveils that the Fallism movement is a continuation of traditions of the Congress Movement, the Pan Africanist Movement and Black Consciousness Movements. As well as social movements that emerged in the 90s and counterculture BC-inspired movements such as the Blackwash movement, a movement that emerged in the early 2000s during a time when black people appeared to be grateful for the bare minimum. Blackwash dropped the proverbial bomb that “94 changed fokol”.

In summary, Transitions is a documentation and thorough contextualisation of what went wrong in the negotiations of transitioning from apartheid to “post-apartheid”. The text amplifies the voices, praxis and significance of a generation that cries for the land of their ancestors, still not in their possession in an era that has officially recorded in its state media “emancipation for all”.