IGNATIA MADALANE

From Paul to Penny: The Emergence and Development of Tsonga Disco (1985-1990s)

Amidst the intense socio-political circumstances in South Africa during the 1980s, black urban music continued to thrive by blending domestic and international music trends giving rise to new styles and genres. When disco made its way to the country in the 1970s, South African musicians began incorporating it into their music, leading to the decline of the formerly notable mbaqanga. This new type of music was given the labels township soul, township soul jive, township jive, or Soweto jive; names derived for the amalgam of influences which the music relied on which included American soul, mbaqanga jive, disco, and township jazz (Hamm 1988).

In this essay I trace the emergence of Tsonga disco, a Tsonga music subgenre which, at its emergence, could be differentiated from the other mentioned township styles such as township soul/jive only by virtue of its progenitor, Paul Ndlovu, who was Tsonga, and the predominantly Tsonga lyrics he used.[1]See Madalane, (2011) for further reading on Tsonga popular music. Further, I discuss the musical techniques employed by producer Peter Moticoce who produced Paul Ndlovu’s music and the techniques used by singer, songwriter and producer Joe Shirimani. I should point out here that Shirimani not only produces his own music, but he also writes and produces music for other artists such as of singer and songwriter Eric Nkovane who is known by his stage name Penny Penny.

Tsonga disco has received very little literary attention with the exception of Max Mojapelo’s brief mention of this subgenre in his collection of memories from his days as a DJ at the South African Broadcasting Corporation, Beyond Memory (2008). In his account Mojapelo highlights key players in this subgenre such as Paul Ndlovu, Peta Teanet, and Penny Penny, all of whom are central to this article.

A cogent factor in the discussion is Fabian Holt’s framework for the analysis of popular music genres in his monograph, Genre in Popular Music (2007), which functions as a guide to exploring how the musicians who came after Paul Ndlovu have built upon Ndlovu’s work and how they have managed to find their own musical voices. Theoretically, I use Bourdieu’s Habitus and Forms of Capital to substantiate my argument. I argue that the music is a reflection and a result of the musicians’ social and historical circumstances. This work draws from masters degree field research conducted between 2009 and 2011 in South Africa. My fieldwork methods included semi-structured interviews with the living musicians[2]See Madalane (2011) for further reading on Tsonga popular music. and music industry practitioners as well as participant observation.

Paul Ndlovu and the emergence of Tsonga Disco

Some scholars describe black South Africa popular music as “crossover” (Allingham 1999: 636), “fusion” (Ballantine 1989: 4), “cross-fertilization” (Coplan 1985: 193), and “hybrid” (Allen 2003a) due to the use of musical elements from more than one music culture. Generally, these terms are used to describe the presence of more than one style or genre in the music. In Afro-American Music, South Africa, and Apartheid (1988), Charles Hamm suggests that the cross-fertilisation or fusion process goes through three stages: importation, imitation and assimilation. By importation, he refers to the process through which the music is brought into the country. Imitation, for Hamm, is when South African musicians “perform … songs in the style in which they were done in the United States or Britain”. Finally, the music is assimilated by merging the imported styles with “black South African performance traditions” (1988: 5). This framework for analysis pertains to much black South African popular music, including Tsonga disco.

As black South African musicians began incorporating disco into their music to create new genres, these new genres were subsequently labelled township jive/soul, and later bubblegum. The music was a blend of both domestic and international styles including mbaqanga, American soul, and disco. Tsonga disco, as a subgenre, thus emerged during this period as a descendant or subgenre of Tsonga neo-tradional music.[3]See Madalane (2011) for discussion on Tsona (neo)tradional music. Prior to its emergence, commercial Tsonga music was primarily made up of choral music, indigenous music, and the neo-traditional music pioneered by Daniel Shirinda, known as General MD Shirinda.

I elaborate and discuss the ‘Tsonga’ prefix in this music elsewhere and do not wish to repeat myself (See Madalane, 2011). To summarize the thesis however, Tsonga disco was given its title, according to my interlocutors, because of Paul Ndlovu’s ethnic background. Through analysis of the music, in the said article, I establish that Ndlovu’s music is very much similar to that of other South African township pop/bubblegum artists such as Sello ‘Chicco’ Twala, Yvonne Chaka Chaka, Brenda Fassie, and Splash.[4]See Coplan (2008) for further discussion on these artists. The difference between Ndlovu and these other artists was seemingly that he came from a particular place associated with “pure” ethnic identity (ibid.).

Paul Ndlovu was among the solo artists that emerged during this period. Ndlovu came from Phalaborwa in Limpopo Province to Johannesburg to pursue his music career. Various sources, including Max Mojapelo (2008), Lulu Masilele (Interview 23 March 2010), James Shikwambana (Interview 12 April 2009), and Peter Moticoe (Interview 4 May 2011), concur that before he became a solo artist, Ndlovu worked with the Big Cats, The Cannibals, Street Kids, the Movers, and Stimela. These are all groups that performed a mixture of musical styles including township jazz, township jive, mbaqanga and township soul.

Masilela cited a misunderstanding with the Movers’ former manager, David Thekwana, as the reason for Ndlovu’s departure from the group. Both Masilela and Mojapelo state that Ndlovu went on to propose a working relationship with Peter “Hitman” Moticoe as his producer when he became a solo artist. Ndlovu thus emerged from this background of having worked with these groups with vast musical experience from which he, together with his producer, would draw inspiration for his own musical identity.

Obed Ngobeni’s Influence

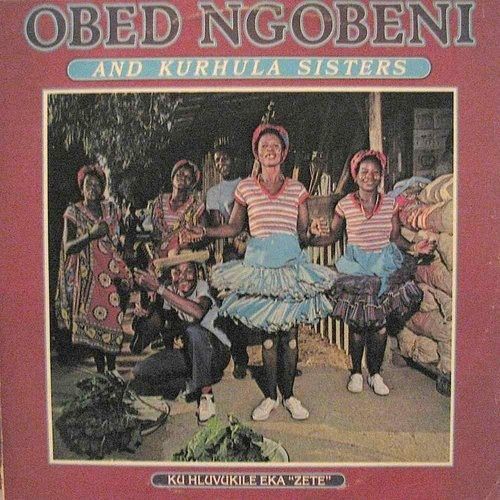

Although Ndlovu was to become the Tsonga disco king, Moticoe credits Obed Ngobeni as the one who paved the way for Ndlovu, a musician who in this regard is also acknowledged by Mojapelo but by none of the people I interviewed. According to Mojapelo and Moticoe, Obed Ngobeni rose to popularity through his hit song Kuhluvikile Eka Zete (1983, “There is progress at Kazet”). The song was produced by Moticoe and later adapted by the popular mbaqanga group Mahlathini and the Mahotela Queens. According to Mojapelo, “the track caught the attention of Harry Belafonte and inspired his album Paradise in Gazankulu (2008: 297). It was because of the success of this song that Ndlovu later approached Moticoe and asked him to become his producer. Moticoe recalled Ndlovu saying “I like what you did with that guy (Obed Ngobeni), I would like you to give me a try as well” (Interview 4 May 2011).

The absence of Ngobeni in the Tsonga disco discourse could be attributed to the fact that Ngobeni’s music is considered Tsonga neo-traditional music,[5]I use the term neo-traditional knowing that its use has been contested by scholars such as Phindile Nhlapho (1998) preferring the music to be called traditional music rather than neo-traditional. Its use here is solely intended for the reader not to mistake this music as indigenous music. a music genre described as being similar to maskanda (Mojapelo 2008: 296; Madalane 2011).[6]General MD Shirinda paved the way for this genre during the late 1950s and early 60s for artists like Elias Baloyi, Samson Mthombeni and Thomas Chauke (see Madalane 2011). Like maskanda, this style is dominated by a lead guitar which is usually played by a male singer, backed by female backing singers (ibid.). The proliferation of this genre, together with other neo-traditional styles such as maskanda and mbaqanga from the 1960s, was entwined with the introduction of Radio Bantu. In the article, “The Constant Companion of Man”, Charles Hamm explicates how the apartheid government’s cultural policy relied on radio, with music being a central method to disseminate its political propaganda (1991).

Hamm unpacks the apartheid system’s cultural policy through scrutiny of the South African Broadcasting Corporation’s (SABC) annual report in which fundamental instructions on the programming and the music to be played on radio were documented. He further notes that in order to “promote the mythology of Separate Development all music programmed on Radio Bantu [was to] relate in some way to the culture of the ‘tribal’ group at which a given service was aimed” (1991: 161). It is from this policy that Tsonga neo-traditional music became popular and musicians like Ngobeni gained so much exposure in the late 1970s when his song, Kuhluvikile eka Zete, was released. The apartheid government’s “separate development” system, its censorship laws and cultural policy that gave precedence to these neo-traditional styles would therefore not have given a platform for rhetorical style shift even though Moticoe had musically diverged from the Tsonga traditional music conventions in Ngobeni’s song. Thus, despite the complexities in musicians’ changing or evolving from one genre to another, as expressed by Jonathan Shaw (2010) and Keith Negus (1999), Kuhluvukile eka Zete could not have, under such circumstances, afforded Ngobeni the platform to become a Tsonga disco/township pop artist.

Even the album sleeve containing the song shows Ngobeni crouching, surrounded by his backing singers, the Kurhula Sisters, adorned in their traditional swibelani (the Tsonga female traditional skirt) and miceka (cloths) in accordance with the visual aesthetics of the classical Tsonga neo-traditional music of the time. Therefore the song’s heavy reliance on a disco beat would not have influenced the way Ngobeni was promoted and marketed. However, Kuhluvukile eka Zete is different from Tsonga neo-traditional music in that the lead guitar that dominates this style is taken to the background in this song. Instead Moticoe relied on a heavy disco thumping bass line to drive the song. In addition, he used the keyboard sound typically found in township soul and/or jive music to support the bass line. This keyboard sound was popular at the time, mainly influenced by American soul and disco, but it was not introduced in Tsonga neo-traditional music until later.

When Paul Ndlovu, having worked with the aforementioned groups, approached Moticoe, who had previously worked with a number of such groups, he was in a better position to be located within the popular apolitical musical genres of the time, which were township soul and disco. He subsequently became the pioneer of so-called Tsonga disco due to, according to Moticoe, his Tsonga ethnic background and his first two hit songs Khombo Ra Mina and Mukon’wana which he sang solely in xiTsonga.[7]See Madalane (2011) for discussion of Tsonga popular music and ethnicity. Though Moticoe’s view that Ndlovu’s music was given a different label from that of his counterparts because of his ethnicity is well justified, it does not close doors for other possible interpretations of this decision, especially considering the year in which Ndlovu released his first songs, 1985, the same year in which the South African government declared a state of emergency.

Considering this particular year and the tense state of the country at the time, it would also not seem illogical to surmise that marrying a specifically South African ethnic group, Tsonga, with a global music genre, disco, could have been an attempt to convey South Africa’s participation in the global cultural sphere. The ethnic part of the label, one could argue, could have been a desperate attempt to show that though South Africans were broken up into different ethnic groups, this did not mean they could not engage with the rest of the world, especially because Ndlovu’s music is undoubtedly very similar to that of his peers. Listening to the compilation CD called Reliable Afro-Pop Hits (2008), released by Gallo gives credence to this hypothesis as well. The CD includes songs by Splash, Alec Khaoli, Patricia Majalisa, and Sipho Mabuse among others. Ndlovu’s song, Cool Me Down is included in this CD. Technically, the music of these artists is very similar, employing the same recording techniques, similar timbres, textures and instrumentation in such a way that each song can only be linked to its owner by their unique voices. Another important fact underpinning this argument is that the music was not labelled by the musicians themselves, but by the companies with which they were signed.[8]See Muff Anderson (1981) for further reading on the relationship between artists and record labels during apartheid.

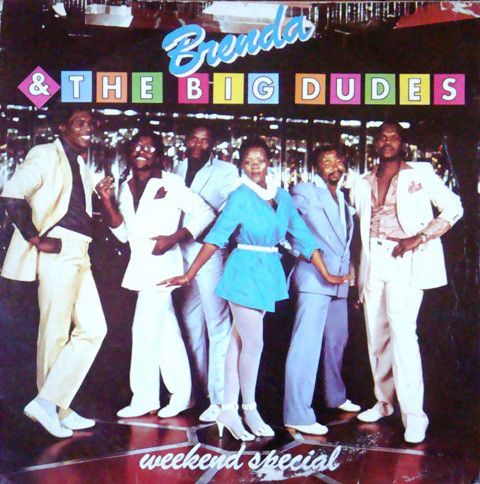

The aesthetics of this music, from the musical parameters to its branding and marketing, completely contradicted the abrasive socio-political atmosphere at the time. Musically, the songs were upbeat, sometimes slow and soulful like American soul and some were groovy, drawing influence from the disco beat. Love themes inspired by both soul and disco music permeated both singles and albums. To compliment these sounds, artists were also decorated in bright coloured costumes and funky hair dos.

The sleeve of Brenda and the Big Dudes’s 1983 hit Weekend’s Special and the video of the same title is an epitome of this trend. The group looks like Donna Summer and the Jackson 5 with Brenda in her mini dress and all the male members in their white suits with their shirts slightly unbuttoned.

Sipho Mabuse could be mistaken for Marvin Gaye on the cover of his Burn Out album. Not surprisingly therefore, Ndlovu’s solo music followed these trends, even though it was dubbed Tsonga disco instead of township soul or disco or jive like that of his compatriots. The similarity of Ndlovu’s music to that of other township pop musicians could also be the reason for Ndlovu’s immediate popularity amongst most South Africans. The music was familiar to them, yet different in the sense that Ndlovu also drew on his Tsonga roots to create his own musical identity, thus giving credence to Holt’s assertion that popular music genres are fluid and musicians are often encouraged to “find their own voices” (2007: 5).

Music of the sailor man[9]Ndlovu’s signature outfit was his sailor hat.

In describing how he worked with Paul Ndlovu’s songs, Moticoe said he was experimenting, fusing elements of what he referred to as “our local brand” and western popular music such as that of Marvin Gaye, Booker T and Jimmy “Hammond” Smith, all of whom are associated with both soul and disco, and especially disco which he declared was the “in thing at the time”. He went on to describe how Ndlovu’s first songs came about:

By that time I was working for a certain company, my previous company, which was Trutone Music. I then joined RPM as a public relations officer. So they just know this guy who can market black music. So I told them, guys this is not my line, my line is producing can I try with this guy, which [was] Paul Ndlovu. They said no we like what you are doing. But eventually I booked studio time. We worked with Paul. We came up with one track and they said ja we like it, but can you go back and do this and that. I never went back and did anything, instead we did another song. I gave it to them, they liked it, and they pressed it and it was a demo (Interview 4 May 2011).

The song that came out of this first studio session was none other than the memorable Khombo Ra Mina (“My Misfortune”). He cited a phrase from the lyrics when he mentioned the song, “wansati waxi dakwa” (a drunkard of a wife). As the story unfolded, Moticoe recited lyrics from some of Ndlovu’s songs, which astounded me as he is not a xiTsonga speaker. Nevertheless, his ability to remember the exact lyrics of the songs points to two important factors. The first is Moticoe’s producer/artist relationship with Ndlovu and the second being the unforgettable nature of the song which may have resulted from being so popular or from Moticoe having played the songs countless times while working on them.

Moticoe’s description of his professional relationship with Ndlovu seems in contrast with what is commonly found in publications where producers from this period are often described as agents of white record labels who told musicians what to do in order to not only produce music that would sell, but music which would also be in accordance with the censorship laws (Coplan 2007; Anderson 1981). Coplan described the producers as indunas (headmen) (2007: 243). Moticoe went on to say:

You see abo (guys like) Paul, you see as a producer you need to make the artist your friend, you wanna know what his problem [is], what is it that can make him perform…even your students, you work on them, you work with them, you must know when he is sad, when he is angry, when he is happy, that must be your business, and make sure that you want him to perform, you must do the right thing, you must make him happy, you see. It’s not just about doing music, befriend him, talk to him, what is your problem; he will help you, and guide you (Interview 4 May 2011).

The second song they worked on was Mukon’wana (“son-in-law”), which Mojapela says was a “hit”. Referring to these two songs, Mojapelo proclaims, “it was clear that the Shangaan-disco music king had arrived” (2008: 143). Naming Ndlovu the king of Shangaan-disco is one of the reasons to consider Ndlovu one of the centre collectives referred to by Holt. By centre collectives, Holt refers to “clusters of specialized subjects that have given direction to a larger network…They include record producers, and above all artists whose iconic status marks them as “leading” figures” (2007: 21). Besides being the first artist to be labelled a Tsonga disco artist, Ndlovu became a “leading” figure within this genre (ibid.). Others later aspired to be like him and drew inspiration from his work.

Though disco was, according to Hamm, “a complex phenomenon” in America, it was perceived as “mindless, apolitical entertainment” in South Africa (1988: 35). As much as Hamm contends that this period (1970s and 80s) was not a favourable period for a “new, apolitical genre of popular music to flourish in the country, but”, he goes on to say, “old patterns persisted: South African record companies released American disco records and the SABC put them on air” (1988: 34). Rob Allingham adds, referring to the local disco, recording techniques that “in some instances the level of musicianship had improved and more sophisticated keyboards came in” (1994: 386). It is these features that would later find their way into Ndlovu’s music as well.

Ndlovu’s music maintained most of the American disco elements which include the thumping bass, synthesizers, drum machines and keyboards (Clarke 1989; Hamm 1988; Starr 2006). The song Hita Famba Moyeni (“We will walk on air”) starts with the synthesized keyboard riffs in Figure 1 and 2.

Figure 1: “Hita Famba Moyeni” as recorded by Paul Ndlovu. Transcription by author.

Figure 2. “Hita Famba Moyeni” as recorded by Paul Ndlovu. Transcription by author.

Then an electric bass interjects playing the following motif:

Figure 3. “Hita Famba Moyeni” as recorded by Paul Ndlovu. Transcription by author.

In most of Ndlovu’s songs, the music is built upon an ostinato bass line. In addition, it is mainly constructed of synthesizer and keyboard riffs that are repeated throughout the song with occasional variations. In certain songs, Ndlovu uses live instruments such as the trumpet in Cool Me Down, and saxophone in Mina Ndzi Rhandza Wena (“I only love you”) and Dyambu Ri Xile (“The sun has risen”). In Mina Ndzi Rhandza Wena the sax is given a short phrase which is repeated throughout the piece with minor variations, while in Dyambu Ri Xile the sax plays an improvisatory role as a solo instrument.

Moticoe expressed his love for live instruments saying that to this day, though he makes use of electronic synthesizers, he always incorporates live instruments in his music. The use of brass in disco was a feature of American disco, though mainly in groups rather than as solo instruments; for example in Stayin Alive, a single from the sound track of the film Saturday Night Never (1977), there are numerous brass stabs (2:00-4:35).

Poetically, Ndlovu’s songs follow the township soul/disco/jive trend of the time with love being the central theme. The didactic nature of Tsonga indigenous music is also used, as Moticoe professed, “you know we were into idioms, you check the one song he says “ixikala xa mukon’wana axiwomi, ikhamba lomkhonyana alomi, lihlala lino ncwala” (the [beer] gourd/calabash of a son-in-law is never or should never run dry. It must always be full of beer) (Interview 4 May 2011). The lyrics are as follows:[10]Lyrics not cited in full.

Mukon’wana

Hi xewetile, vakon’wana

Mi pfukile xana?

Ahee

Switsakisa ngopfu kumi vona mingena

lamutini, Vasivara

Leswi miswi lavaka mitaswikuma

axi omi xamukon’wana

Loko milava swibyalana, mitaswikuma

axi omi xamukon’wana

Loko milava xibiyana, mitaxikuma

axi omi xamukon’wana

Loko milaxiputla, mitaxikuma, vasivara

axi omi xamukon’wana

Son-in-Law

Greetings, our in-laws

Are you well

Salutation

It is indeed splendid to see you coming to

visit us here at home, brothers-in-law

Whatever you want, you will get

It [the beer gourd] does not run dry

f you want some beer, you will get it

It [the beer gourd] does not run dry

If you want some beer, you will get it

It [the beer gourd] does not run dry

If you want hot stuff (whiskey or brandy),

you will get it

It [the beer gourd] does not run dry

The response phrase a xi omi xa mukon’wana (it does not run dry), is derived from the phrase mentioned by Moticoe as ixikala (in Tsonga), ikhamba (in Zulu), which refers to the traditional gourd or calabash used to serve beer. Thus, in this song reference is made to the traditional way the Tsonga serve beer. The song describes relations between in-laws and point to how in-laws should be treated according to Tsonga tradition.

In Khombo Ra Mina on the other hand, a man laments his misfortune for being given a drunkard for a wife.

Khombo ra mina

My Misfortune

Mhani yoo, khombo ra mina[11]Mhane means mother. In this context it is however used as an exclamation of weeping out of frustration, equivalent to Oh dear me, etc.

Lamentation, my misfortune

Vani tekela wansati va ni tekela xidakwa

They took (gave me) a wife for me, they gave me a drunkard

Andzi n’wi lavi mino, wansati wa xi dakwa

I don’t want her, a wife who is a drunkard

Andzi n’wi lavi mino, wansati wa dlakuta

I don’t want her, a filthy wife

A min’wi voni n’wino, wa dedeleka mhanee

Can’t you see, she stumbles all over [from being drunk]

A min’wi voni n’wino, wa dedeleka mhanee

Can’t you see, she stumbles all over [from being drunk]

Mhani yoo, khombo ra mina

Lamentation, my misfortune

Anga etleli notlela

She does not even sleep

U tlela swidakanini

She sleeps in taverns

Anga kukuli la kaya

She does not sweep the house

Anga swikoti kusweka

She can’t even cook

The lyrics indicate that the man did not have the liberty of choosing his own wife, a practice in contrast to the one described by Junod in which young Tsonga men choose their own mates (1962: 97), unless he made the girl pregnant before marriage in which case he would be forced to “buy her in marriage” (ibid.).[12]Junod also described that elders may start complaining if a young man is of appropriate age to marry and still does not have a wife. The researcher is also aware of cases where a wife may be chosen for a young man by elders if the first wife is considered problematic, is barren, or lazy. Also according to Junod, though women brew the beer (ibid, 108) and are allowed to consume it (Johnston 1973; 1974), getting intoxicated is not the aim of Tsonga beer-drinking (1974: 293). Johnston described rural beer-drinking occasions as “formal and dignified” therefore it would seem appropriate for a man to complain if his wife is a drunkard, as Ndlovu does in the song. These two songs are clearly influenced by Tsonga idioms which Moticoe referred to, thus attesting to his point about having drawn inspiration from “our own music” and affirming the point about black South African popular music being a “fusion”.

Ndlovu’s other songs follow the love theme common in soul and disco lyrics. An example is the song Tsakane (a person’s name, meaning “rejoice”). The lyrics are in English and Tsonga. Tsakane is one of several songs in which Ndlovu declares or proposes love to a woman. Others include I Wanna Know Your Name in which Ndlovu’s narrator asks a woman for her name because he is “a lonely man” and he “just wants to know her”; Mina Ndzi Rhandza Wena (“I love only you”); Hita Famba Moyeni (“We will walk on air”); and Cool Me Down.[13] “We will walk on air” is a direct translation but in the song it refers to flying in an airplane. Another influence found within these songs is what Portia Maultsby refers to as soul music’s “teenage love songs” (2006: 278), due to the predominance of romance and social relationship, which are prevalent in these songs.

That Ndlovu mixed languages and succeeded while Jonny Clegg and Sipho Mcunu’s Woza Friday suffered a different fate is not surprising (Clegg and Drewett, 2006: 128). Besides the fact that Ndlovu was a solo artist, without a white man singing alongside him, Coplan observed that by this time government censorship was half-hearted. “The reality was that the National Party regime, forced to defend its core political real estate of apartheid legal structure and power itself, had ceded the cultural domain of black culture to the blacks and fellow travellers, and popular musicians had been among the first and most aggressive in its appropriation”, proclaims Coplan (2007: 296). Nevertheless, Moticoe admitted to having been cautious of the censorship laws in order to avoid getting his music banned. He elaborated by saying, “I had friends in the radio [industry], mostly they were ex-teachers, you could only get into radio if you were an ex-teacher, so I would check lyrics with them first, is this right if I say this, is it not vulgar or anything” (Interview 4 May 2011)?

Ndlovu’s Popularity

In addition to writing songs that audiences would relate to and that could be approved for airplay, Moticoe also attributed Ndlovu’s performance skills as one of the reasons he became a highly sought-after musician.

He used to be very good, we used to tour. In our group, like the Movers, we used to have different genres, we used to play from 20h00 until 00h00. Today’s acts [are] 45 minutes [long]. We used to play from 20h00 to 00h00. So performing, he was one of the best in the country, so he had this type of dance called jive, so he was famous for it. It’s a pity I don’t have videos (Interview 4 May 2011).

Mojapelo credits the power of radio for Ndlovu’s popularity. He claims that Ndlovu was “one musician who opened [his] eyes to the overwhelming power of radio” (2008: 143). The power of media in genre formation is also acknowledged by Holt (2007: 21). Moticoe also confirmed that Ndlovu’s music was played by various radio stations. Ironically, however, he also admitted that Ndlovu’s music was not well received by some people working for the Tsonga radio station. He claims that this resistance was because he, the producer, was not Tsonga and therefore he was viewed as an intruder to their culture. Nonetheless, he went on to say that as soon as they heard that Ndlovu’s music was getting popular with other radio stations, the Tsonga station followed suit and started playing the music. The initial resistance to Ndlovu’s music by his “own” people because he worked with an “outsider” is evidence of the effects of the separate development system. Another point to consider, however, is that Ndlovu was the first musician to predominantly use xiTsonga lyrics in a music genre that was not associated with the Tsonga people.

Prior to Ndlovu, the only Tsonga music genres that existed were indigenous music, choral music and the neo-traditional style that was pioneered by Shirinda. It is therefore a combination of these factors that left Ndlovu’s music in the hearts of many, including musicians who came after him. Sadly though, as Mojapelo says, “Ndlovu died tragically on 16 September 1986” (2008: 143), a victim of a tragic car accident.

Holt goes on to say that “genre boundaries are contingent upon the social spaces in which they emerge” (2007: 14). For Tsonga disco, this statement is quite apt as, according to Moticoe, Ndlovu’s music was intended to be dance or party music. He explained how he eschewed the protest song route, choosing the traditional idioms, soul and disco instead. Choosing the protest song route would have meant risking their music being banned or themselves being harassed or arrested by government officials. Moticoe reasoned, whether times are good or bad, people will always want to have a good time and it was his duty as a producer to look ahead of the time and guide his musician to write music that would outlive its period, pointing out to the fact that one hardly hears Mzwake Mbuli or Blondie Makhene’s music today. Thus their choice not to sing songs with politically loaded lyrics may seem to be a politically motivated stance on the surface, but it also has residue of a long term, sustainable music career and vision when analysed closely.

Stayin’ Alive – Peta Teanet Sustains Ndlovu’s Legacy

Ndlovu’s premature death in 1986 left a vacuum in Tsonga popular music which was soon filled by Peta Teanet (1966-1996), another Tsonga disco artist whose life would be prematurely cut short. Very little is known about Teanet and efforts to find anyone close to him have been unsuccessful.[14] Peter Moticoe said that he worked with Teanet only on one project, and does not know anything else about him. Gallo Records failed to provide me with Teanet’s artist profile after several requests. The little that is known is quoted by Mojapelo from CD sleeve notes:

He was born Ntahleng Teanet Peta on 16 June 1966 in Letsitele. His mother Emma sang many traditional songs to the child and that laid the foundation from which Ntahleng’s future music inspiration would benefit. His family later moved to the village of Thapane outside Tzaneen where he grew up. Teanet started singing publicly at the age of 18 in church at Relela village, where he also helped pray for the troubled souls. Later he played keyboard and sang for a group called Relela. The band caught attention of Radio Tsonga’s music producer, Roy Ngobeni. He exposed them to the broader public. After the passing away of his hero [Paul Ndlovu], Teanet went down to Johannesburg with the aim of sustaining Paul’s legacy. After knocking on many doors, he eventually met the leader of Mordillo [Ndlovu’s band], Lefty Rhikhoto, who was prepared to produce him. Using the name Peta Teanet, his debut album Maxaka (1998, Challenger) hit the streets (2008: 144-145, cited from CD sleeve of the album The Best of Peta Teanet, 2004).

After his solo album Maxaka (We are relatives), Teanet went on to release other albums such as Divorce Case (1989), Peta Teanet and The Special Servants (1991), Saka Naye Jive (Jive with him jive, 1992), and Utakutsakisa (He will make you happy, 1993). He was shot dead in 1996 while “promoting his forthcoming album” (ibid.).

Teanet acknowledges Ndlovu’s influence in some of his songs; however, as Holt puts it, he went on to “find [his] own voice” (2007: 5). The song Maxaka (‘we are relatives’) from his debut album of the same name begins with two keyboard riffs and a synthesized percussive rhythm. The first riff enters with the percussive rhythm; the second riff half way through the first one as if responding to it. Once the riffs are in play, the bass drops in just before Teanet gruffly whispers the word Maxaka.

The two keyboard riffs and the bass line form the instrumental foundation of this song. They are maintained throughout the piece and do not change, though the riffs are occasionally omitted while the bass and the percussion parts remain and vice versa. The use of synthesizer and keyboard riffs and a consistent bass motive was also a feature of Ndlovu’s music.

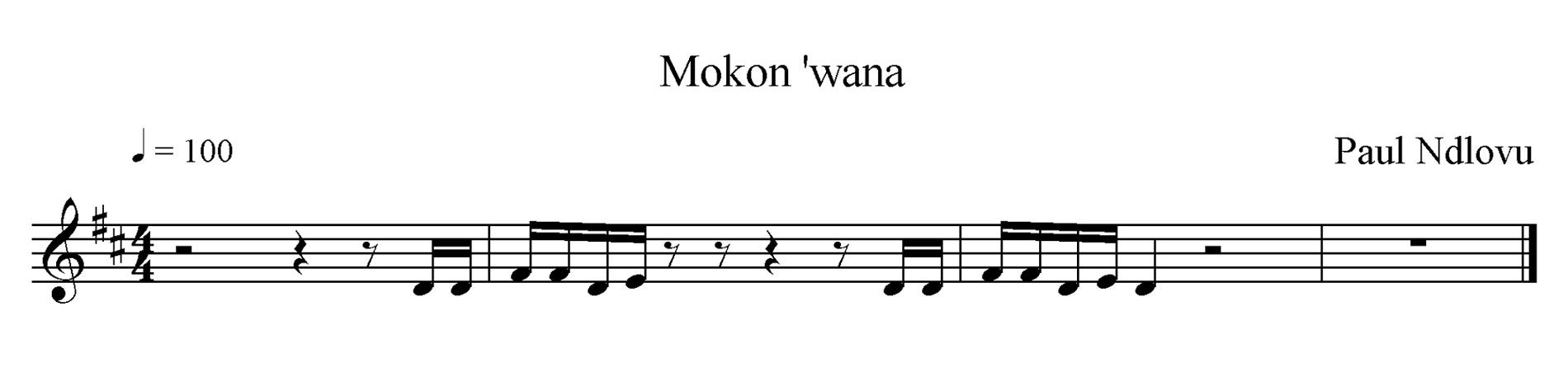

Teanet’s admiration for Ndlovu is depicted in the song Hisarisile (“We said our goodbyes”, or “Goodbye”) in which he replicates in imitation one of the sounds found in at least three of Ndlovu’s songs, Hita Famba Moyeni (“We will walk on air”), Cool Me Down and Khombo Ra Mina (“My misfortune”).[15]In ‘Hita Famba Moyeni’ the sound can be heard at 00:03, in ‘Cool Me Down’ at 00:57, and in ‘Khombo Ra Mina’ at 00:04. In all songs the sound keeps recurring throughout the track This sound clip, probably a pitch bend, resembles a synthesized sustained muffled descending ‘u’ sound. In the same song Teanet also reproduces a melodic motif, the fundamental sound of which is that of an African marimba, found in Ndlovu’s Mukon’wana (‘Son-in-law’). In Ndlovu’s song the motif appears as in Figure 6 while Teanet’s version is shown in Figure 7.

Figure 4.[16]This song should be spelt ‘Mukon’wana’, but on the CD sleeve it was spelt ‘Mokon’wana’. “Mukon’wana” as recorded by Paul Ndlovu. Transcription by author.

Figure 5. “Hisarisile” as recorded by Peta Teanet. Transcription by author.

The motif is the same except that they appear in different keys, and the tempo is much faster in Teanet’s, set to, in disco terms, 115 bpm Mukon’wana is 100 bpm. In the latter, the motif appears very early in the piece at 0:07 when it enters with another keyboard riff. Initially it comes and goes, until it returns just before the chorus where after its distinctive marimba sound dominates the piece. One is drawn more to it than any of the other riffs. Both the motifs have a synthesised marimba sound.

In Hisarisile the marimba melodic motif only appears after all the instrumentation, including the voice, has been laid down. Though there are a number of other melodic motifs within this song, the marimba motif dominates. Its busyness thickens, creating a distinctive sound. The use of the pitch bend sound and referencing the marimba motif can be thought of as Teanet’s acknowledgment of Ndlovu’s influence on him and as a tribute to the Tsonga star. His admiration of Ndlovu has been spoken about by Moticoe (Interview 4 May 2011) and Mojapelo (2008: 144).

Though Ndlovu’s influence is present in Teanet’s music, Teanet has his own idiolect, the term used by Brackett for “the style trait associated with [a] particular performer” (2000: 10). A notable feature of Teanet’s music that differentiates it from that of Ndlovu is the tendency to use children’s voices in the backing vocals. This practice was a common feature in South African township pop during this time as artists like Chicco (in We Can Dance and Teacher We Love), and Brenda Fassie (Ag, Shame Lovie) employed the same technique. In Teanet’s music, use of this feature seems to occur when the subject of the song is related to children.

A song such as Matswele (“Breasts”) uses children’s voices in this way as the chorus sings: Tsotsi skatshwara matswele (Tsotsi don’t touch my breasts). The song tells of a man who comes from ‘nowhere’ and touches a girl’s breasts. Then it goes on to say, kgasi oakgago (they are not yours).

Teanet’s music is generally up-tempo in comparison with that of Ndlovu. Teanet surfaced in the late 1980s, at a time when American house and hip-hop had made its way into the country (Mojapelo 2008; Haupt 2008; Watkins 2004). The influence of these varieties of music on Teanet is explicit, and may account for the faster tempo of Teanet’s music. I’m a Dancer clearly shows these influences. Structured on a 127 bpm beat and built on a synthesized thumping bass line, Teanet raps the words in I’m A Dancer; that is, he rhymes the lyrics rhythmically as opposed to singing them melodically.[17] See Popular Music Genres (Borthwick and Moy, 2004) for description of the different types of rap.

I’m a Dancer, however, more typically draws on elements of house music. According to Rick Snoman, for example, 127 bpm is a typical tempo in house music (2004: 271). The track is in 4/4, the kick is laid firmly on all the beats, a clap is added in addition to the kick and the hi-hat, and the synthesized bass is kept relatively simple and remains consistent throughout the piece while the electronic piano solos above the bass and the kick. These are all typical features of house music (271-278).

The early 1990s saw the emergence of a township music style called kwaito.[18] See David Coplan’s ‘God Rock Africa’ (2005), Gavin Steingo’s ‘South African Music After Apartheid’ (2005), Thokozani Mhlambi’s ‘Kwaitofabulous’ (2004), and Lara Allen’s ‘Kwaito versus Cross-over’ (2004) for further discussions on kwaito. One of kwaito’s defining features at the time was that the lyrics “consisted of a few of the latest catch phrases repeated and played against each other, rather than lengthy poetry”, and draws influences from hip-hop, American and European dance music, including house, techno, and pop (Allen 2004: 85). Though Teanet raps in the song I’m a Dancer, the manner in which he does this is more consistent with how kwaito lyrics work rather than the poetic, complex and lengthy lyrics of American rap music. In addition to the repetition of short phrases, “let’s dance” and “I’m a rapper”, the subject matter also suggests kwaito’s influence on Teanet’s song. It is about having fun, a dominant theme of kwaito during this period (2004: 87). The subject of Saka Naye Jive (“Jive with him/her”) is also typical of kwaito.

It is about the township dance style uku saka, meaning to dance (in a specific way), a dance which I did as a teenager in the early 1990s and which involves putting one’s hand on the head and the other on the buttocks while bending all the way down.[19] The complete phrase of this dance is penti yiwele, saka uyidobe, meaning the panty has fallen, go down and get it; hence the bending in the dance movement. This situates specifically South African dance music in the context of other global dance music genres the lyrics of which, since disco, have often functioned self-referentially.[20] Arthur Mafokate is the most famous kwaito artist to predominantly use lyrics that refer to a dance. See for example the tracks ‘Mnike’, ‘Kwasa’, and ‘Twalatsa’. Although Ndlovu’s music was intended for the dance floor, as Moticoe noted, Ndlovu did not explicitly refer to dancing in his songs. Conversely Teanet’s songs often include lyrics about dancing. Saka Naye Jive, China Ndoda (“Dance, man”) and Double Phashash, all make clear reference to dancing.

In China Ndoda for example he commands the men to dance; he challenges the young men to dance because they are being defeated by another group of dancers and suggests that in the old days they knew how to dance and have a good time. The recurring dance and playful themes found in Teanet’s music depicts social or national cultural consciousness as kwaito became a national phenomenon.

However, in Maxaka Teanet complains to his grandparents for not having warned him about the girl he married as it later became known that they were related. In Tsonga tradition, it is taboo for relatives to marry. Teanet thus continues the tradition of Tsonga musicians tackling domestic matters. It is commonly known that Teanet’s backing singers were his wives (Mojapelo 2008: 145). N’wayingwana (“Daughter of Yingwana”) makes reference to polygamy as the song’s narrator sings about his wife (from Johannesburg) making life difficult for his first wife. In his treatment of the subject, Henri Junod addressed the consequences of wife rivalry in Tsonga polygamy (1962: 282-289). Teanet’s song not only speaks of the continuous existence of polygamy among the Tsonga but also speaks to the challenges of the practice that are still very much part of today’s polygamous marriages. Making reference to the traditional themes such as cultural taboos, polygamy and traditional dances like xigubu and muchongolo (referred to in the song China Ndoda), is a depiction of ethnic pride, a feature which is not explicit in Ndlovu’s music.

Teanet’s music is also eclectic, another important feature of his song-writing. This can be noted by the difference between I’m a Dancer, Maxaka (“We are relatives”), Nwayingwana (“Daughter of Yingwana”) and I Love You Africa (Remix). The songs draw on such diverse styles that, without Teanet’s identifiable voice, it would be difficult to attribute them to the same artist. As discussed, I’m a Dancer mainly draws influence from house music, in Maxaka Ndlovu’s influence can be detected. In N’wayingwana the lead guitar gives the song a Zimbabwean aesthetic, while in I Love you Africa an electro sound can be heard. While Ndlovu’s music could almost be described as “predictable” in the sense that one song is similar to another, Teanet’s music is filled with diverse sounds and influences that, in the words of Brenda Fassie, Ngeke uncomfeme (“You cannot confirm a person”).[21]From the song ‘Umuntu Uyatshitsha’ (‘a person changes’) from the album of the same name, released in 1996.

Teanet’s fusion of different genres, styles and traditions in his music, his versatile voice, and his ability to be unpredictable in his songwriting, not only distinguished his music from that of his predecessor, Ndlovu, but also created a unique musical language within the Tsonga music world that has not since been heard. While Ndlovu started Tsonga disco, Teanet built on and developed the subgenre, doing so in a way that Ndlovu the founder did not. Important to note is that his career spanned from the transition period from apartheid up to the few years following the democratic elections. Thus the eclectic nature of his music, including the lyrics, could be attributed to the changes within the socio-political sphere. While political negotiations were taking place, culturally, South African saw an influx of different international genres which Teanet clearly appropriated and fused with domestic genres to create his own musical identity. He was subsequently labeled the king of Shangaan-disco by music commentators, thus also placing him amongst the centre collectives. Following Teanet’s death in 1996, Joe Shirimani and Penny Penny took over the Tsonga disco music scene.

Originally published in the JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL LIBRARY OF AFRICAN MUSIC. Re-published here with kind permission of the author and the editor of the Journal, Dr. Lee Watkins.

Read Part 2 in the next issue of herri.

Allen, Lara V.

2004 “Kwaito versus Crossed-over: Music and Identity during South Africa’s Rainbow Years, 1994-1996.” Social Dynamics, 30(2): 82-111.

2003a “Commerce, Politics, and Musical Hybridity: Vocalizing Urban Black South African Identity during the 1950s.” Ethnomusicology, 47(2): 228-249.

2003b “Representation, Gender and Women in Black South Africa Popular Music, 1948-1960.” PhD Dissertation: University of Cambridge, Cambridge.

Allingham, Rob

1999 “South Africa: Popular Music, the Nation of Voice.” in S. Broughton et al, eds. World Music: The Rough Guide, London: The Rough Guides. 638-657.

1994 “Southern Africa.” In S. Broughton et al, eds. World Music: The Rough Guide, London: The Rough Guides. 371-389.

Anderson. Muff

1981 Music in the Mix: The Story of South African Popular Music. Johannesburg: Ravan Press.

Ansell, Gwen.

2004 Soweto Blues; Jazz and Politics in South Africa. New York: Continuum.

Ballantine, Christopher

1989 “A Brief History of South African Popular Music.” Popular Music, 8(3): 305-310.

Barker, Hugh, Yuval Taylor,eds

2007 Faking it: The Quest for Authenticity in Popular Music. New York: W.W. Norton.

Beard, David, Kenneth Gloag

2005 Musicology: The Key Concepts. London and New York: Routledge.

Bidder. Sean

2001 Pump Up the Volume: A History of House. London: Channel 4 Books

Borthwick, Stuart, Ron Moy

2004 Popular Music Genres: An Introduction. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Bourdieu, Pierre

1984 Disticntion: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste.Cambridge, Harvard University Press.

1986 “Forms of Capital.” In J. Richardson, ed. Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education, New York: Greenwood, 241-258.

Brackett, David

2005 “Questions of Genre in Black Popular Music.” Black Music Research Journal, 25(1/2): 73-91.

Broughton, Simon, Mark Ellingham, Richard Trillo, eds.

1999 World Music: Volume 1: Africa, Europe and the Middle East: The Rough Guide. London: Penguin Books.

Burnim, Mellonnee V., Portia K. Maultsby, eds.

2006 African American Music: An Introduction. New York and London: Routledge.

Coplan. David B

2007 In Township Tonight! Three centuries of South African Black City Music and Theatre, 2nd edition. Auckland Park: Jacana Media.

2005 “God Rock Africa: Thoughts on Politics in Popular Black Performance in South Africa.” African Studies, 64(1): 9-27.

1985 In Township Tonight! South Africa’s Black City Music and Theatre. New York: Longman Publishers.

Drewett, Michael, Martin Cloonan, eds.

2006 Popular Music and Censorship in Africa. Aldershot: Ashgate.

Dyer, Richard

1979 “In Defence of Disco.” Gay Left: A Gay Socialist Journal, 8: 20-23.

Greenfell, Michael

2008 Pierre Bourdieu: The Key Concepts. Stocksfield: Acuman.

Hamm, Charles

1991 “The Constant Companion of Man: Separate Development, Radio Bantu and Music.” Popular Music, 10(2): 147-173.

1988 Afro-American Music, South Africa, and Apartheid. New York: Institute for Studies in American Music.

Haupt. Adam

2008 Stealing Empire: P2P, intellectual property and hip-hop subversion. Cape Town: HSRC Press.

Holt. Fabian

2007 Genre in Popular Music. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press

Johnston, F.T.

1974 “The Role of Music in Shangana-Tsonga Social Institutions.” Current Anthropology, 15(1): 73-76.

1973a “The Social Determinants of Tsonga Musical Behaviour.” International Review of Aesthetics and Sociology of Music, 4(1): 108-130.

1973b “The Cultural Role of the Tsonga Beer-Drink Music.” Year of the International Folk Music Council, 5: 132-155.

Junod. Henry A.

1962[1912-13] The Life of a South African Tribe. New York: University Books Inc.

Madalane, Ignatia

2011 “Ximatsatsa: Exploring Genre in Contemporary Tsonga Popular Music.”Masters in Music Dissertation: University of the Witswatersrand, Johannesburg.

Meintjes, Louise

2005 “Reaching Overseas: South African Engineers, Technology and Tradition.” In Paul D. Green and Thomas Porcello, eds. Wired for Sound: Engineering and Technologies in Sonic Culture, Middletown: Wesleyan University Press. 23-46.

Mhlambi, Thokozani

2004 “Kwaitofabulous: The Study of a South African Urban Genre.”Journal of the Musical Arts in Africa, 1: 116-127.

Mojapelo. Max

2008 Beyond Memory: Recording the History, Moments and Memories of South African Music. Sello Galane, ed. Somerset West: African Minds.

Negus. Keith

1999 Music Genres and Corporate Cultures. London and New York: Routledge.

Shaw. Jonathan

2010 [2007] The South African Music Business. Johannesburg: Ada Enup

Snoman. Rick

2004 The Dance Music Manual. Tools, Toys and Techniques. Oxford: Burlington MA Focal.

Starr, Larry, Christopher Waterman

2006 American Popular Music: The Rock Years. New York: Oxford University Press

Steingo, Gavin

2005 “South African Music After Apartheid: Kwaito, the “Party Politic,” and the Appropriation of Gold as a sign of Success.” Popular Music and Society, 28(3): 333-357.

Ngobeni, Obed & Kurhula Sisters.

1983 Kuhluvukile eka “Zete”, Heads Music Ent: LP EAD 1008 (CD).

Ndlovu, Paul.

2009 The Unforgettable, Gallo Records: CDTIG 426 (CD).

2002 Paul Ndlovu’s Greatest Hits, Gallo Record Company: CDTIG401 (CD).

Penny Penny.

2007 Tamakwaya 8, Xibebebe, Cool Spot Productions: CDLION112 (CD).

2007 Shanwari Yanga, Cool Spot Productions: CDLION113 (CDN) (CD).

1996 La Phinda Inshangane, Shandel Music: CDSHAN 69D (CD).

1995 Yogo Yogo, Shandel Music: CDSHAN 49R (CD).

Shirimani, Joe.

2007/8 Tambilu Yanga, Shirimani Music Productions: CDSMP002 (CDM) (CD).

2003 The Best of Joe Shirimani, BMG Africa CDBMG: (CLL) 3005 (CD).

1995 Nivuyile, Paradide Music/BMG Records Africa: CDPTM(WL) 120 (CD).

Summer, Donna.

2002 The Universal Masters Collection, Universal Music: GSCD 437 (CD).

1994 Endless Summer: Donna Summer’s Greatest Hits, Polygram Records: FPBCD047 (CD).

Teanet, Peta.

2008 King of Shangaan Disco, The CCP Record Company: CDMAC(GSB) 205 (CD).

2004 The Best Of, Gallo Record Company: CDGSP 3061 (CD).

1999 Greatest Hits, Mac-Villa Music (Pty) Ltd: CDMVM 512 (CD).

1995 Double Pashash, RPM Record Company: CDJVML 132R (CD).

Various Artists.

2008 Reliable Afro-Pop Hits, Gallo Record Company: CDGSP 3142 (ADN) (CD).

Lens, Rob. Johannesburg , South Africa, 28 January 2011.

Masilela, Lulu. Johannesburg, South Africa, 23 March 2010.

Moticoe, Peter. Soweto, South Africa, 4 May 2011.

Mtshali, Themba. Johannesburg, South Africa, 28 January 2011.

Nkovani, Eric [Penny Penny]. Pretoria (Tshwane), South Africa, 4 April 2010.

Oosthuisen, Marius. Johannesburg, South Africa, 28 January 2011.

Shikwambana, James. Polokwane, South Africa, 12 April 2009.

Shirimani, Joe. Pretoria (Tswane), South Africa, 3 April 2009.

| 1. | ↑ | See Madalane, (2011) for further reading on Tsonga popular music. |

| 2. | ↑ | See Madalane (2011) for further reading on Tsonga popular music. |

| 3. | ↑ | See Madalane (2011) for discussion on Tsona (neo)tradional music. |

| 4. | ↑ | See Coplan (2008) for further discussion on these artists. |

| 5. | ↑ | I use the term neo-traditional knowing that its use has been contested by scholars such as Phindile Nhlapho (1998) preferring the music to be called traditional music rather than neo-traditional. Its use here is solely intended for the reader not to mistake this music as indigenous music. |

| 6. | ↑ | General MD Shirinda paved the way for this genre during the late 1950s and early 60s for artists like Elias Baloyi, Samson Mthombeni and Thomas Chauke (see Madalane 2011). |

| 7. | ↑ | See Madalane (2011) for discussion of Tsonga popular music and ethnicity. |

| 8. | ↑ | See Muff Anderson (1981) for further reading on the relationship between artists and record labels during apartheid. |

| 9. | ↑ | Ndlovu’s signature outfit was his sailor hat. |

| 10. | ↑ | Lyrics not cited in full. |

| 11. | ↑ | Mhane means mother. In this context it is however used as an exclamation of weeping out of frustration, equivalent to Oh dear me, etc. |

| 12. | ↑ | Junod also described that elders may start complaining if a young man is of appropriate age to marry and still does not have a wife. The researcher is also aware of cases where a wife may be chosen for a young man by elders if the first wife is considered problematic, is barren, or lazy. |

| 13. | ↑ | “We will walk on air” is a direct translation but in the song it refers to flying in an airplane. |

| 14. | ↑ | Peter Moticoe said that he worked with Teanet only on one project, and does not know anything else about him. Gallo Records failed to provide me with Teanet’s artist profile after several requests. |

| 15. | ↑ | In ‘Hita Famba Moyeni’ the sound can be heard at 00:03, in ‘Cool Me Down’ at 00:57, and in ‘Khombo Ra Mina’ at 00:04. In all songs the sound keeps recurring throughout the track |

| 16. | ↑ | This song should be spelt ‘Mukon’wana’, but on the CD sleeve it was spelt ‘Mokon’wana’. |

| 17. | ↑ | See Popular Music Genres (Borthwick and Moy, 2004) for description of the different types of rap. |

| 18. | ↑ | See David Coplan’s ‘God Rock Africa’ (2005), Gavin Steingo’s ‘South African Music After Apartheid’ (2005), Thokozani Mhlambi’s ‘Kwaitofabulous’ (2004), and Lara Allen’s ‘Kwaito versus Cross-over’ (2004) for further discussions on kwaito. |

| 19. | ↑ | The complete phrase of this dance is penti yiwele, saka uyidobe, meaning the panty has fallen, go down and get it; hence the bending in the dance movement. |

| 20. | ↑ | Arthur Mafokate is the most famous kwaito artist to predominantly use lyrics that refer to a dance. See for example the tracks ‘Mnike’, ‘Kwasa’, and ‘Twalatsa’. |

| 21. | ↑ | From the song ‘Umuntu Uyatshitsha’ (‘a person changes’) from the album of the same name, released in 1996. |