ERNIE LARSEN

Escape Routes

An academic in an online forum recently posed the question of the role(s) that documentary films (may) have made in holding to account the historic role of the State’s repressive apparatus. That sounds like a tall order but even so I think that it’s also necessary to consider with that framing not only individual films but the sustained pivotal role of certain filmmakers—as well as what one might call the afterlives of radical film. In this regard, no Western filmmaker comes to mind as more exemplary than Rene Vautier, who, of course, made the first French anti-colonial film Africa 50 maybe the first ever anti-colonial film) and was imprisoned for it, at the very beginning of his career. In 2008, my collaborator (in film, curating, love, anarchist politics, and other adventures) Sherry Millner and I programmed several of Vautier’s films at the Oberhausen Film Festival, as key elements of our ten-part “Border-Crossers and Troublemakers” series. We invited Vautier to attend and he greatly surprised us by agreeing and participating. In years past, though regularly invited he’d always refused. We regarded his decision to attend as a nod of solidarity.

While speaking, following our screening of his film Le Glas (The Death Knell, 1964), which concerns the impending execution of three revolutionaries in then-Rhodesia, Vautier made a crucial point. Even though the film failed in its demand that the British state act to prevent the execution, it was used repeatedly in the decades thereafter in countless anti-colonialist events and situations. He said, for instance, that Mandela (after his release from prison) openly saluted Le Glas for its forceful effect as a result of a number of clandestine screenings in South Africa. One should, he thought, never foreclose the implicit potential of radical culture, no matter how dark its initial reception. Another such example, a state-censored film with an immediate afterlife that both Vautier and Fanon had a hand in: Yann Masson and Olga Poliakoff’s J’ai Huit Ans (1961).

In that case, being censored was a gift to this anti-colonialist film made in support of the Algerian revolution—in that the resulting controversy promoted hundreds of clandestine screenings throughout France.

Le Glas, a sublime rant, in speaking at once of colonial history and of its present, turned out to speak with equal immediacy to the future(s) of anti-colonialist struggle. Our audience at Oberhausen was riveted by Vautier’s claim, his hard-won insistence that the pathways to the future are never entirely blocked. Vautier’s electrifying presence—he was 80 years old or, as he wryly put it, 4 times 20 years old—in effect turned a conventional structure of the Film Festival, the post-screening director’s Q&A into an event.

By event, I mean, at least, a structured moment that sparkled, however briefly, with the potential to change life, to exceed the structure allotted to it. On the way out of the screening I spoke to a young man, a filmmaker, who said he’d been making formalist films and never would again, after tonight, after seeing Vautier. He’d only make political films now.

In other words, such an event, unplanned in its details, can at its best produce another fragile temporary/temporal structure capable of challenging a relatively passive audience with enough unpredictable energy at the given moment into becoming viewer-participants who find themselves becoming willfully implicated in the issues and affects raised by the films in the program. This is and will remain a provisional formulation. In large part, this is because one soon learns as an organizing curator that such events are themselves in essence unrepeatable, that they must therefore be reinvented each time to remain effective. In other words, the singularity of an event (as opposed to the obvious fact that a film is always the same film) is one possible key to the expansion of a political potential.

There is nothing new or original about such an assertion. In our research, for example, we find that the pre-World War I French anarchist film association, Le Cinema du Peuple, which is apparently the first such cooperative in film history, when they first screened La Commune, directed by the peripatetic Spanish anarchist Armand Guerra, at the Palais des Fetes in Paris, assumed the necessity of creating such an event, building in speakers, contexts, music, etc. The film itself, drawing on revolutionary memory, depicts a series of tableaux from the 1871 Paris Commune. It ends with a remarkable group shot of surviving Communards in 1914, a commemoration that in effect melds for a few seconds the historical fiction of the earlier scenes with the still living collective and actual embodiment of an epochal event.

Since 2008 we have screened programs of five to eight short-form (from one to thirty minutes in duration) experimental political films in a considerable variety of unconventional non-theatrical venues in the U.S. and Eastern and Southern Europe (and in Beirut). Such venues include collective anarchist and otherwise anti-authoritarian social centers, store-fronts, exterior courtyards, bookfairs, squats, in a forest camp at a longstanding protest against corporate goldmining – and at the (illegal) No Border encampment at Aristotle University in Thessaloniki, Greece, in 2016, projected on a white sheet stretched between two trees.

While we have also done screenings at museums and student centers, we are most drawn to presenting formally challenging political culture at such unstable sites of political intervention.

Gradually and sometimes suddenly, we have learned that for the deliberate attempt to turn a screening into some sort of politicized event to succeed, a certain relatively indefinable mix of elements or ingredients tend to be desirable. Phrased as values or qualities, these include such aspects as: presence, immediacy, context, spontaneity, interruption, discussion, surprise. We tend not to repeat the same program twice, in part so that we don’t necessarily know what to expect—building surprises into the structure. We are often willing to or encourage dialogic interruptions, questions and comments between films—though at the same time appreciate the collisions and unexpected juxtapositions of the selected films and the order in which they are screened. The audience is somehow encouraged to achieve something of the sometimes boisterous status of a temporary assembly. The locality of the screening often dictates the direction of the discussion: at a screening in a social center in Sofia, the discussion veered off from a film that depicted police violence against African migrants in the streets of Paris to the repressive actions of police in Sofia—and never returned to discussion of the film. That seemed to count as a success, in that case. We are fortunate that there are two of us—who are in some sort of dialogue with each other as well as the audience. This somehow often provokes audiences. In post-screening discussions, members of the (often activist) audience will engage in considerable arguments or discussion with each other that may be tangential to the films but no less engaged. In screening films at unconventional venues we find that we de-stabilize the viewing situation, which has the effect of allowing whoever attends to move with considerable ease out of the essentially passive role (unchallenged comfort) allotted to the typical paying consumer. Or could it be that our audiences are typically already engaged—and are therefore all the more willing to follow the twists of history represented unconventionally by the films?

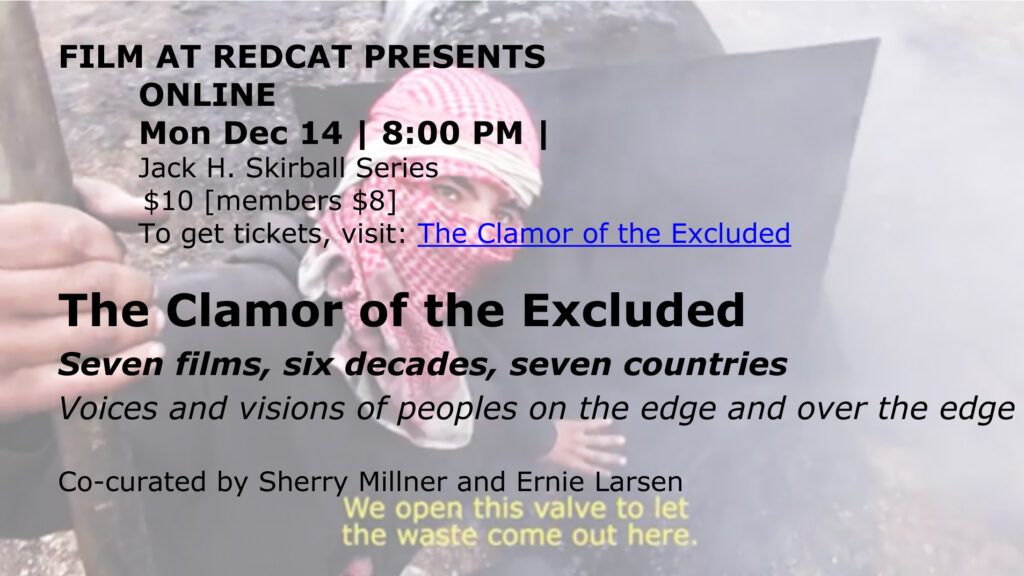

All that said, and believed and experienced, in early December 2020, in the still dire suspension of the pandemic, we lived through the virtual inverse of these conditions and expectations for a globalcast of a screening, as graciously invited by Berenice Reynaud, curator at RedCat, located at the grand Disney Hall in downtown Los Angeles. This would be a more-or-less conventional venue in normal times but we put together what I called The Clamor of the Excluded, a mix of seven films, made over the course of six decades, in seven countries, “voices and visions of peoples on the edge and over the edge,” in this way evoking the potential reach of the locked-down audiences stuck in their homes, wherever they might find themselves—as were we, in New York City, three thousand miles from RedCat.

This is how I described the intentions of the program:

We have been incubating this collection of short films for decades. We saw a few of them as far back as the late 1960s. They were projected on the walls of lofts or in funky theaters on the Lower East Side of New York City. The audiences were made up of hippies, impatient radicals, artists, and troublemakers—people who, like us, believed they were going to change the world. So the collection of films we are in the process of assembling is the distillation of our lifelong engagement with the intersection between the stirring histories of struggles for freedom across the globe and the wide-ranging, often surprising, history of short-form experimental non-fiction media… an engagement both passionate and critical.

These films make propositions – or “escape routes” (a phrase borrowed from filmmaker Jill Godmilow, who has at times collaborate with us), from exhausted classical documentary forms. They each employ critical interventions intended to contest, resist, or imaginatively overturn repressive conditions, stale culture, the violence of the state, patriarchy, racism, the rule of global capital.

We are aiming, in our collections of such films at a gradual construction of an alternative history – a history that has at times been blocked, repressed, censored or hijacked – of short-form radical experimental non-fiction media, from 1914 up to the present. The films that we selected address radical potentiality. They ask and often answer the complex question of how political resistance can be articulated in forms that are not only appositely representative of resistance but that also embody that shape-shifting force in their own diverse historical moments and contradictions.

Today or tomorrow any and all of us are very likely to be caught up in the crossfire of our era’s global upheavals and sudden revolts. The films shown on this page offer precise and often deeply affecting visions that evoke previously underexplored potential for common understanding of these unending crises.

According to the French critic and filmmaker Jean-Louis Comolli:

“Defeating or overcoming the existing order of things requires the invention of forms that are different to those serving to repress our consciousness and our movements.”

The requirement to which Comolli refers should, we feel, encompass the invention of forms of life, of politics, and aesthetic forms, as an intentional project that produces the conditions through which such revolutionary change could begin to be achieved. And the invention of such forms—in life, politics, aesthetics– should always take experimental routes.

Our search for these too little-known and thus under-valued films continues… We hope that our archeological effort, which often meant dusting off, translating, and subtitling uniquely moving films never before seen by English-speaking audiences, will prove to be as much a discovery for the spectators as they have been for us.

And the films:

Alonzo Crawford: Crowded, 1978, 10 min, USA

When the inmates of the grotesquely overcrowded Baltimore City Jail sued the city and state, African-American director Alonzo Crawford, on a budget of $400, documented conditions inside – and on the strength of that unyieldingly attentive visual evidence, the prisoners won.

Aryan Kaganof: Threnody for the Victims of Marikana, 2014, 27 min, South Africa

On August 16, 2012 the South African Police opened fire on a crowd of striking platinum workers, killing 34 and injuring 78. This three-part film uses symphonic and other music, found footage, theoretical analysis, and irony to arrive at a new understanding, both philosophical and visceral, of how the massacre could have happened – under a government ruled by the once-revolutionary ANC.

Millner & Larsen: How Do Animals and Plants Live? 2020, 29 min, USA

While inquiring into the forcible eviction and immediate demolition of the self-organized anarchist-supported migrant squat Orfanotrofeio in Thessaloniki, Greece, in July 2016, this experimental video essay extrapolates on the proposition that “no one is illegal” in the renewed if fragile context of the common.

Rozh Ahmad: Crude Living on Oil in Syria, 2014, 20 min, Syria

The journalist Rozh Ahmad – at a ramshackle roadside refinery – relentlessly portrays the terrifying despoliation of a village, a people, and a landscape all at once, caught in the pincers of an endless war.

Kamran Shirdel: Tehran is the Capital of Iran, 1966, 17.40 min, Iran

This film, censored even before it was completed, sets affecting, often harrowing images of the discarded urban poor against recitations of official reports and schoolbooks. Shirdel’s searing vision was undoubtedly seasoned by study at the Centro Sperimentale di Cinematografia in Rome. At considerable cost to his career, he inaugurated an Iranian version of neo-realism – a take-no-prisoners style of direction.

Zelimir Zilnik: Black Film, 1971, 14 min, Yugoslavia

In a last-ditch gamble to “solve the homeless problem” in the workers’ state of Yugoslavia, the filmmaker invites six homeless men (ignored by the “socialist” government) into his own apartment … And lives to tell the tale.

Los Viumasters: Xochimilco 1914, 2010, 4.5 min, Mexico

On the morning of December 4th, 1914, Pancho Villa and Emiliano Zapata met for the first time. An original stenographic record of their conversation, just hours before they took control of Mexico City, exists. A mere century later, this playful film animates the words of these revolutionary heroes and their historic repercussions.

Following the screening, Berenice Reynaud spoke with us online via globalzoom for close to an hour. What we experienced with the definite exception of Berenice’s expert and engaged comments was the negation of that attempt we have regularly made to turn a screening into an event—for many obvious reasons, beyond anyone’s control. But this does bring up one other perhaps obvious but unmentioned element, beyond the abstraction and absence and severe exclusion imposed by virtual screenings, these provisional imperfect attempts not to foreclose absolutely the experience of politicized culture even in a pandemic. Implied within the values of immediacy and spontaneity, of contact visual, aural, even tactile, is a deliberate limitation of scale—the ability and necessity in most political/cultural events to be together is clearly, or even by definition dependent on face-to-face encounter. Before the advent of the pandemic it would never have occurred to me to make such a distinction, so obvious, so necessary.

This thought gives another dimension to one of the films we sought in 2008 to screen at the Oberhausen Festival, Guy Debord’s Critique of Separation. Only three days before we were due to fly to Germany that year we received word from the good folks working to put the Festival together that Debord’s widow had quite unexpectedly refused permission to screen the film—apparently because his films were never to be screened in a program with any films not made by situationists. Sherry and I were outraged by this of course—not least because we’d constructed an entire 90 minute program around Debord’s short film. So we decided to remake Critique of Separation in the three days available to us—in the form of a two-screen film, using Debord’s black and white version, screen left and adjacent to it, screen right, our color version, Paris then and New York City now. Sherry did a voiceover in English, reducing Debord’s voiceover to a murmur. We managed to finish it just moments before we left for the airport. We saw it for the first time when it was screened at Oberhausen, as Partial Critique of Separation, enacting the core situationist strategy of détournement.