TOM WHYMAN

Night Music 3: The Ghost has been summoned

5/8/19. I have received an email, in which I have been asked to write about the South African composer Arnold Van Wyk’s 1958 piano piece, Nagmusiek (Night Music). Specifically: I have been asked to write about this Van Wyk piece, and the philosophical concept of hauntology – which I have just published an article about in a magazine in my native UK. Nagmusiek, I am told, is Van Wyk’s “most hauntological” composition.

I have been sent a recording of the piece, by the pianist Daniel-Ben Pienaar. I have never heard of Van Wyk before. Downloading it, what I hear is something very austere, very introverted – but also very self-abnegating. It’s hard to know what exactly the piece is trying to express, because it seems to be trying to represent an absence – the absence, indeed, of the very self who is doing the expressing. There is clearly a deep sadness – but sadness over what? Is Van Wyk heartbroken, grief-stricken, in despair? It is almost as if the piece is trying to tip-toe around its own subject matter.

I try to flesh out my understanding with some details of the provenance of the piece. “It was always outside of music here in South Africa,” I am told in that initial email. “There was nowhere to fit it into and so it vanished… Nagmusiek never really existed in the first place.” Van Wyk was an Afrikaner, and his works are sometimes thought to reflect a romantic Afrikaaner nationalism. But, with a naturally melancholy disposition, Van Wyk was (apparently) not really a political person: to the extent, at any rate, that this is even possible, especially if you come from somewhere like South Africa. “There are no overt politics in Van Wyk’s music,” I am told. “No covert politics either. None. That in itself is deeply political.”

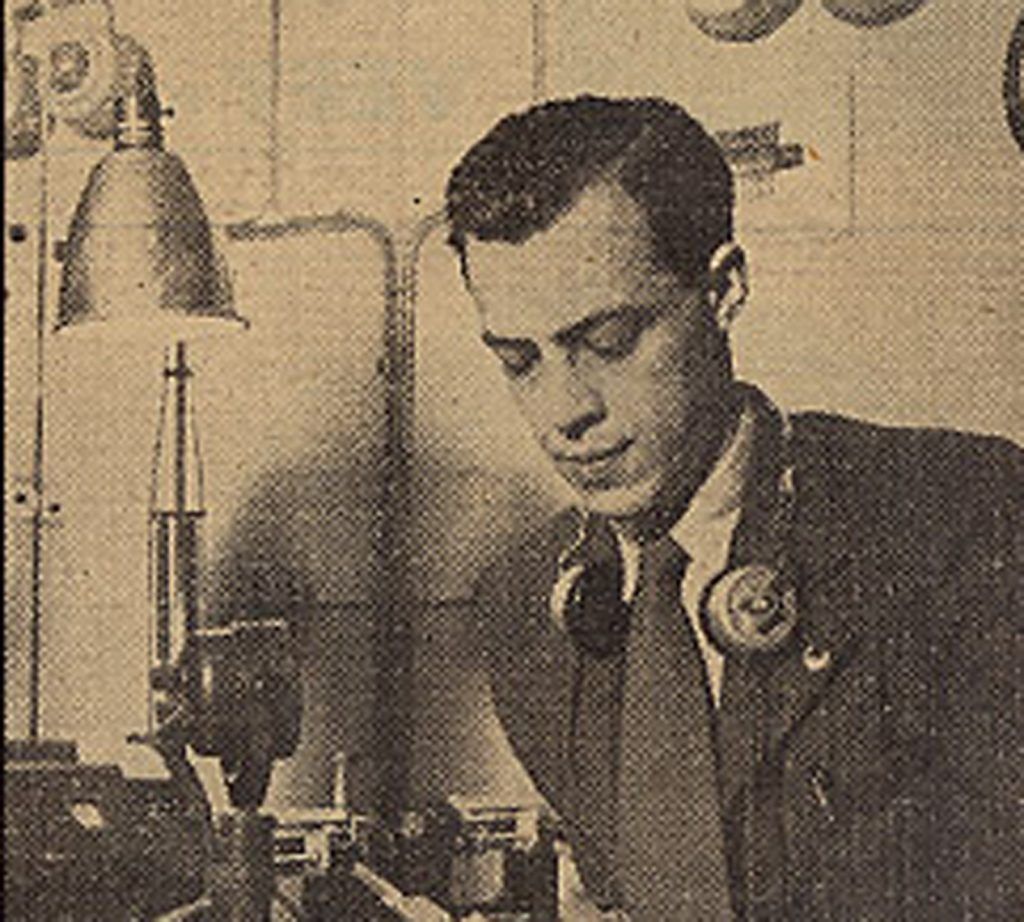

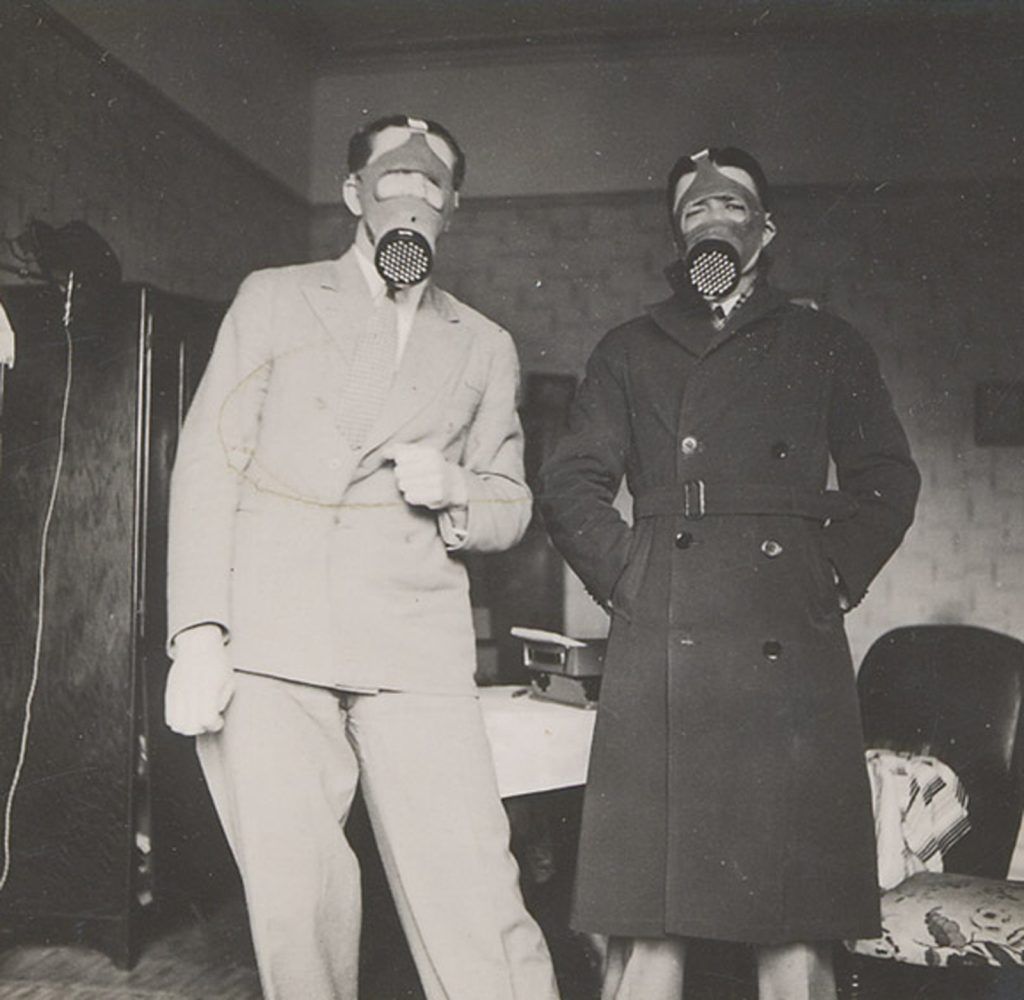

In the early 1940s, I discover, Van Wyk lived in London, where he studied at the Royal Academy of Music and worked for the Afrikaans section of the BBC. “My eight years in England,” Van Wyk would later recall, “are unforgettable. It was wonderful… I can’t think of a word in English for it.” During this time, Van Wyk met and became an “intimate friend” of the brilliant young Australian pianist Noel Mewton-Wood, who also worked closely with Benjamin Britten. On the 5th of December, 1953, Mewton-Wood committed suicide by drinking hydrogen cyanide after the death of his lover, William Fedrick, from a burst appendix – it was to Mewton-Wood’s memory that Nagmusiek was dedicated. For Van Wyk, ‘Nagmusiek was not only his most important work: its writing, which took at least three years, was one of the bitterest struggles I can remember or imagine.”

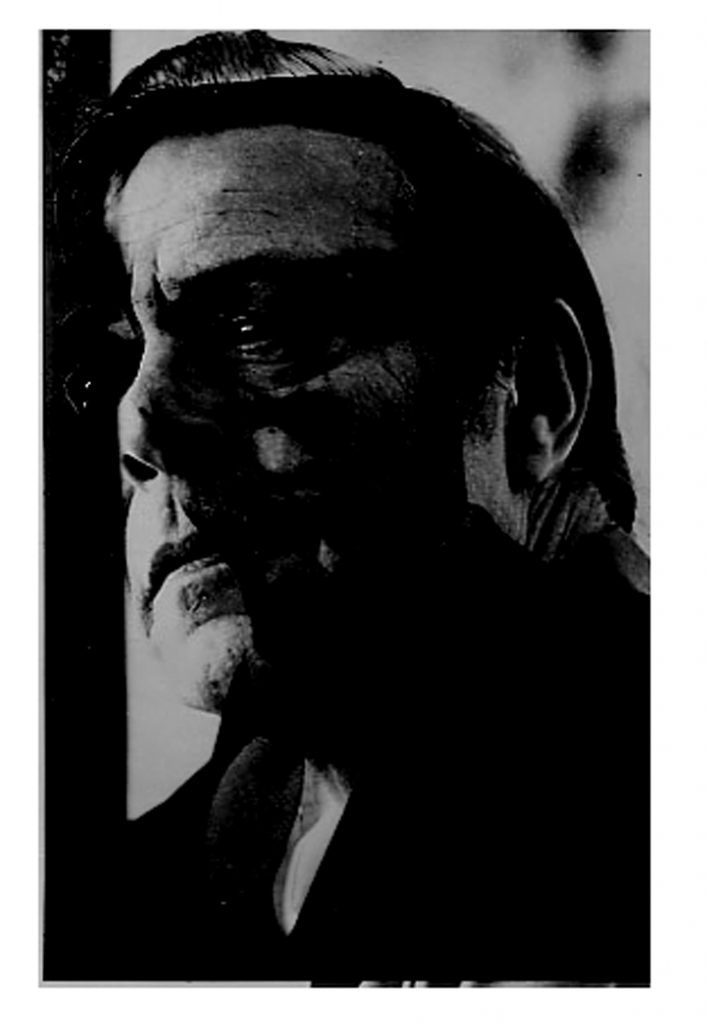

I am sent a biography of Van Wyk, by courier from somewhere in South Africa, to my flat in the north of England. It is a beautiful artefact, also named Nagmusiek, by a scholar named Stephanus Muller. It comes in three volumes: two little grey ones, ‘I’ and ‘II’, which as far as I can tell consist mostly of notes; and a third, big and blue, which is the actual biography. I later find out that the book is not even just a biography, but also a novel, about a biographer named ‘Stephanus Muller’, in the process of sabotaging his own creation. The volumes come bound in a big blue box, with a black-and-white photograph depicting a man’s taut, nervous hands – presumably Van Wyk’s. I flick through them. There are glimpses of illumination, here and there: some photographs; brief passages in English. But other than that, almost the entire thing is in Afrikaans. I cannot learn Afrikaans; I don’t know anyone who can help me read it. The book exists: but, like the music, this existence lies for the most part beyond my comprehension.

“But the facts are these,” I read in one glimpse of English from the book, a fragment of a letter by Van Wyk, I think to someone named Freda Baron:

“1. of course I am afraid of Death – but since I have to die sometime it does not especially matter when and how;

2. that I am finally convinced that my happiness is not of this world. The next world (if such there be) cannot be harder to bear than this one. There is a possibility of a good God being kind to tired people, and allowing them to sleep and know no consciousness. Not even the consciousness of Joy. Just nothing. Just oblivion…

I love you.”

November 2019

‘Hauntology’ was originally coined by Jacques Derrida in his book Specters of Marx not only as a serious philosophical concept but as a pun: if “ontology” is the study of what is, then “hauntology,” which sounds very much like “ontology” if you say it in a French accent, is the study of what is not. But what does not exist might nevertheless, Derrida observes, have certain very real effects: the not, he tells us, has a “presence,” though “virtual” and “insubstantial.” “The logic of haunting,” is “larger and more powerful than an ontology or a thinking of Being”; it harbours within itself “teleology” – the doctrine of design or purpose – and “eschatology” – the study of the end times.

The canonical example here is Marx’s “spectre” that is “haunting Europe – the spectre of Communism.” In 1848, when Marx and Engels wrote The Communist Manifesto, Communism did not yet exist – had yet to be instantiated, anywhere, at all. But its threat, its promise, its possibility, was causing “all the Powers of old Europe” to enter into “a holy alliance to exorcize” it: “Pope and Czar, Metternich and Guizot, French Radical and German police spies.” And this process was, of course, repeated with still greater intensity throughout the course of the 20th century. Thus something not yet present was nevertheless really doing something politically: causing the powers-that-be to react against it.

More recently, Derrida’s concept was revived by the late British critic and philosopher Mark Fisher, most notably in his 2013 book Ghosts of My Life. For Fisher, hauntology was a way of responding to what Franco ‘Biffo’ Berardi identified as “the slow cancellation of the future”: the way in which, since the early 90s, cultural time has seemed – despite the massive technological innovations associated with the internet – to “[fold] back on itself.”

In the 20th century, Fisher tells us, popular culture was in the grip of a “recombinational delirium, which made it feel as if newness was infinitely available.” He asks us to consider, for instance, the trajectory of popular music – from Elvis to the Beatles to punk to hip-hop to jungle. “Play a jungle record from 1993 to someone in 1989, and it would have sounded like something so new that it would have challenged them to rethink what music was, or could be.”

By contrast, “the 21st century is oppressed by a crushing sense of finitude and exhaustion.” According to Fisher, our present cultural moment is characterised by a “formal nostalgia” in accordance with which ostensibly ‘new’ things can be produced only through the imitation and pastiche of old forms. Fisher relates first seeing the video for ‘I Bet You Look Good on the Dancefloor’ by the Arctic Monkeys: “I genuinely believed,” he says, “that it was some lost artefact from circa 1980. Everything in the video – the lighting, the haircuts, the clothes – had been assembled to give to impression that this was a performance on… [the now-defunct BBC television music show] The Old Grey Whistle Test. Furthermore, there was no discordance between the look and the sound.” There would have been nothing especially wrong about this, Fisher implies, if the Arctic Monkeys had been explicitly positioned as a ‘retro’ group – but they were not. “By 2005,” when ‘I Bet You Look Good on the Dancefloor’ came out, “there was no ‘now’ with which to contrast their retrospection.”

Initially Fisher, alongside with the music critic Simon Reynolds, applied the term ‘hauntology’ to a loose constellation of artists, which they came to see as ‘the hauntologists’. These were predominantly experimental electronic musicians – Fisher names William Basinski, Burial, The Caretaker, and The Focus Group – whose work was “suffused with an overwhelming melancholy,” and “preoccupied with the way in which technology materialised memory – hence a fascination with television, vinyl records, audiotape, and with the sounds of these technologies breaking down.” The “principal sonic signature of hauntology” was the use of crackle, the surface noise made by a needle on vinyl.” Crackle is inherently hauntological because it refuses to grant us the illusion that we are listening to anything other than a recording: a recording which was made at a particular, distinct time in the past. For Derrida, hauntological spectres like that of communism are a sign that – and here he quotes Hamlet – “the time is out of joint,” that the present is “non-contemporaneous” with itself. Crackle is thus a way of representing this non-contemporaneity aesthetically.

Hauntological music thus casts us back, somehow, into the past. But it does not do this to indulge nostalgia – as with the music of groups like the Arctic Monkeys. The point of hauntological music is not to replicate a particular period, Fisher insists, – but rather to engage the listener with the possibilities that certain bygone eras were felt to contain. Fisher focuses, in particular, on the UK in the 1970s, before the rise of Thatcher and the instantiation of neoliberalism; the age of what he called “capitalist realism.”

“What should haunt us is not the no longer of actually existing social democracy, but the not yet of the futures that popular modernism trained us to expect, but which never materialised. These spectres – the spectres of lost futures – reproach the formal nostalgia of the capitalist realist world.”

Hauntology shows us, despite everything, that we don’t have to live as we presently do: that there could be another way of organising things. In reviving the past, it seeks to move the present to the future.

In both Derrida and Fisher, then, hauntology is explicitly political. The possibilities it names are thus collective ones: they are possibilities that can be experienced, and acted upon, only in the context of our shared life, our shared memory; animated by our shared agency.

But then doesn’t it seem a bit strange to call Nagmusiek hauntological? – when there is nothing about Van Wyk’s piece that is at all collective?

Though certainly “suffused with melancholy,” as the music of Burial or William Basinski is, it is hard to imagine a piece of music more shorn of the social. (By contrast Burial’s music is evocative of London in the early 00s; William Basinski’s of 9/11). Neo-romantic, Nagmusiek is even rather isolated from the more general context of 20th century composition. It does not dwell on history – it attempts to remove itself from it.

But that doesn’t necessarily mean that Nagmusiek isn’t hauntological. Perhaps indeed there is another hauntology, that Nagmusiek could be said to exemplify: a hauntology of the self.

Naturally, our lives – as our societies, as our histories – contain various possibilities within them. When we look back at our lives, we become aware of what some of these possibilities might have been: in regret, we wish that certain others had become actual instead. At times, this sort of reflection can bring about transformative action in the present: I realise, perhaps, that I should have been a schoolteacher, and so go back to university to retrain. But of course some things are, simply, lost. A goalkeeper cannot save a penalty kick in the past by choosing, this time, to dive the other way – the final is settled forever. When a friend dies, we cannot get them back: cannot tell them, this time, how much we loved them, how much they mean to us – tell them please don’t do that, please don’t go. The world in which Van Wyk might have saved Mewton-Woods was already lost by the time the composer, in South Africa, received word of his death.

We all exist, each one of us, as part of a vast ongoing cycle of irreconcilable regret. Genetically, each of us exists as an almost infinitesimally unlikely actuality: our parents had to meet; our parents had to fuck at the exact right moment in time to produce us. Probably even the temperature in the bed where they did it (or the couch, or against a wall, or whatever), had to be exactly the right temperature for the sperm that was part us to reach the egg that was the rest, and penetrate it – ahead of all the other sperm, all the many millions of babies that could have been, but never were (it is different, of course, for people conceived via IVF – but not that different). If either of our parents had ever done anything differently, anything at all, right up until the moment of conception – then probably we would never have existed. And not only our parents but their parents, and their parents before that… Every single one of us, the negative image of the paths not taken: some better, some worse – all necessary. We are always, only, ourselves – but this self is formed by so much that is contingent, arbitrary, and inscrutable. It can never quite be present to us, and we can never quite be reconciled to it.

Nagmusiek, as I’ve said, attempts to represent an absence – in so doing, it makes said absence present. This paradoxical present-absence is, I think, the very possibility of a different self, whose choices were made as part of a different past; from which was formed a present that maybe could have once been, but never can be now. Nagmusiek mourns Mewton-Woods, but it is not, strictly speaking, haunted by him: it is haunted by a different Van Wyk.

There is an illuminating comparison to be made here with Summertime, by Van Wyk’s fellow Afrikaner J.M. Coetzee. Technically Summertime, which was published in 2009, serves to cap the trilogy of autobiographical novels that Coetzee began with Boyhood and Youth. But it is a remarkably strange autobiography – consisting for the most part of fictional interviews conducted by an English biographer, Mr. Vincent, with people who are supposed to have known Coetzee in the early 1970s, when the future Nobel Prize winner had recently returned to South Africa from the United States. In the world of the book Coetzee, for his part, is already dead.

An Englishman, like me, the ostensible writer of Summertime is a stranger not only to Coetzee’s life, but to his cultural milieu – it is never quite clear if Vincent’s interviewees are telling the truth, in part because Vincent lacks sufficient understanding to make sense of when they might be lying. But Coetzee is made to seem a stranger to his own life too. The interviewees, all but one of whom are women, talk of Coetzee as if he were not quite human: passionless, almost neuter – unworldly, impractical; “radically incomplete.” To Vincent, Coetzee was manifestly a great writer. But hardly any of the interviewees are even particularly familiar with his work.

“I know he had many admirers,” says the final subject, a colleague Coetzee supposedly had an affair with while teaching at the University of Cape Town. “He was not awarded the Nobel Prize for nothing… But – to be serious for a moment – in all the time I was with him I never had the feeling I was with an exceptional person, a truly exceptional human being… I experienced no flash of lightning from him that suddenly illuminated the world… I would say that his work lacks ambition… Nowhere do you get the feeling of a writer deforming his medium in order to say what has never been said before, which is to me the mark of great writing. Too cool, too neat, I would say. Too easy. Too lacking in passion. That’s all.”

But the book does not consist solely of (fictitious) interviews. The Vincent sections are bookended by two others, ‘Notebooks 1972-75’ and ‘Notebooks: undated fragments’ in which Coetzee speaks for himself – although admittedly in the third person, not the first. In one of the later entries, which is from a time when Coetzee was living with his father, precariously employed after fleeing the US in some never-specified disgrace, with no apparent better future to look forward to, he contemplates suicide.

“In the back pages of his diary he makes lists. One of them is headed Ways of Doing Away with Oneself. In the left-hand column he lists Methods, in the right-hand column Drawbacks.

Of the ways of doing away with oneself he has listed, the one he favours, on mature consideration, is drowning, that is to say, driving to Fish Hoek at night, parking near the deserted end of the beach, undressing in the car, putting on swimming trunks (why?), crossing the sand and entering the water (it will have to be a moonlit night), breasting the waves, striking out into the dark, swimming to the limit of physical endurance, then letting fate takes its course.”

In this entry, Coetzee conjures up the spectre of a world in which there never was any J.M. Coetzee the Nobel Prize-winning novelist: in which the corpse he left behind was simply that of a dead man, not a great one; a loser who spent his last days living with his elderly father, in Cape Town, having never escaped the place he was born.

In the end, though, the death the book closes with is not Coetzee’s in the 1970s, but his father’s. In the final notebook entry, Coetzee snr. falls sick with gum and throat problems, and then is diagnosed with cancer. The doctors find a tumour on his larynx, which they have urgently removed, leaving the old man unable to talk. Two weeks later, he returns to the house he shares with his son in an ambulance. Coetzee is given a sheet of instructions entitled ‘Laryngectomy – Care of Patients’ – and then the two are left to their own devices.

“He [Coetzee] draws back. ‘I can’t do this,’ he says. The ambulancemen exchange glances, shrug. It is not their business, taking care of the wound, taking care of the patient. Their business is to convey the patient to his or her place of residence. After that it is the patient’s business, or the patient’s family’s business, or else no one’s business.

It used to be that he, John, had too little employment. Now that is about to change. Now he will have as much employment as he can handle, as much and more. He is going to have to abandon some of his personal projects and be a nurse.

Alternatively, if he will not be a nurse, he must announce to his father: I cannot face the prospect of ministering to you day and night. I am going to abandon you. Goodbye. One or the other: there is no third way.”

In this passage, Coetzee confronts the decision to which any effective hauntology of the self must, in some way, be committed. In order to actualise the possibilities it identifies, a hauntology of the self must do a certain violence to the self, which also means that which has formed it – must wrench itself up, however far it can manage, out up from the cycle of regret; must make a break with its own past. A hauntology of the self summons the self as a ghost – stages a séance. But the séance must be followed by an exorcism.

But this, I think, is something Nagmusiek quite fails to do. I think of Van Wyk’s hands on the cover of Muller’s biography: taut and nervous, trembling instead of plunging the knife in. This is what Nagmusiek sounds like, the whole way through. The ghost has been summoned – but what then?