As I write this, the role played by Western art music in the apartheid imaginary is still inadequately understood, nowhere more so than in South African institutions of higher learning where the study of such music presupposed, during apartheid, subjects of culture linked to Europe and the existence of a certain praxis legitimated by attempts to establish a communication community with a European musical past.[1]I adapt the line of reasoning in this paragraph from Bill Readings’s book, The University in Ruins (Cambridge, Mass., 1996), where he writes not about music, but about the role of the English literary canon in North American universities. In the twenty-first century, the assumptions that necessitated the building and expansion of South African university music departments during colonial rule and apartheid no longer hold politically or ideologically, and hence there is no longer a need for the institutional apparatus to sustain the fiction that South Africans are the musical offspring of a European male canon. Western music in South Africa has little more than a century of intrinsic cultural content, and the role of the Western music-oriented Music Department in South Africa is therefore not to bring to light the content of national or local culture. The establishment of Western cultural content at such departments is also not the realisation of an immanent cultural essence, but an act of colonial subjugation: the paradoxical choice of a tradition. Thus the form of the European idea of culture is preserved in such departments, but without its inherent content, which instead depends on the social contract concluded in the era of colonial rule and the white supremacist understandings of culture prevalent in apartheid South Africa, rather than on the continuity of an historical tradition.[2] Ibid., 35.

Upon preparing The Journey to the South for publication, Stellenbosch University was plunged into a crisis of collective conscience by the publication of an article entitled ‘Age- and education-related effects on cognitive functioning in Colored South African women’.[3]Sharné Nieuwoudt, Kasha Elizabeth Dickie, Carla Coetsee, Louise Engelbrecht and Elmarie Terblanche, ‘Age- and Education-related Effects on Cognitive Functioning in Colored South African Women’, Aging, Neuropsychology, and Cognition (2 May 2019). Twenty-five years after the political demise of apartheid, this (now retracted) article illustrated how the university had failed, as an institution, adequately to interrogate how its research culture and ethics continue to be shaped by the past. It should stand to reason that this interrogation is not only a matter for academic debate,[4]For discussions and reactions to the article by Stellenbosch University, see [accessed 1 September 2019]. but that it should also have a demonstrable impact on the administering of ethics, and the kinds of decisions made with regard to support for vulnerable individuals who work to change this culture for the better. The idea that Stellenbosch University emerged in a democratic dispensation as a value-free tabula rasa upon which a new and invigorated research culture could be based, is simply not rationally defensible. What the article on so-called cognitive functioning ‘in Colored South African women’ has confirmed, is that an institutional ethic that feigns ignorance of this fact and its implications is no ethics at all.

The entire manifesto which is The Journey to the South is the work of the historical author, Stephanus Muller. The opaqueness of the parable results from its deliberate entangling of history, fiction, and plagiarised fiction to fashion a knotted register of expression. How does the parable relate to history if its historical ruminations have been taken verbatim from Hesse’s Journey to the East, thus making its historical pose not only fiction but somebody else’s fiction? And to what extent is this plagiarised fiction contaminated by history and reinvention when one realises that sentences have been changed by historical events and new fiction, grafted into its phrases through additions and omissions? The parable suggests that history is an idea rather than an article of faith, that fiction is neither original (the function of Hesse’s text) nor fictitious (the function of history), and that meaning resides somewhere between the binaries consistent with oppositional structures of meaning (history and fiction). In a word, the parable (and its subsequent critiques) might well be the kind of baffling register named by Roland Barthes as the ‘Neutral’, a register ill-served by explanations, illuminating commentary, corrections of others’ work, fear of contamination (between history and fiction, between Hesse and Muller), hierarchies of meaning (elided in the celebration of nuance) or transparent referencing of allusions and references.[5]See Roland Barthes, The Neutral: Lecture Course at the Collège de France (1977-1978), texts established, annotated and presented by Thomas Clertc under direction of Eric Marty, tr. Rosalind E. Krauss and Denis Hollier (New York, 2005). I should like to thank Christine Lucia for pointing me to this text. The ‘Active of the Neutral’, Barthes writes, relates to its ‘thought-out’, deliberate’ character, attentive to the present, unafraid of ‘the banality that is within us’ (our hurt, our shame, our defeat, our death).[6]Ibid., 81.

Singapore Statement on Research Integrity (clause 11): ‘Reporting Irresponsible Research Practices: Researchers should report to the appropriate authorities any suspected research misconduct, including fabrication …’

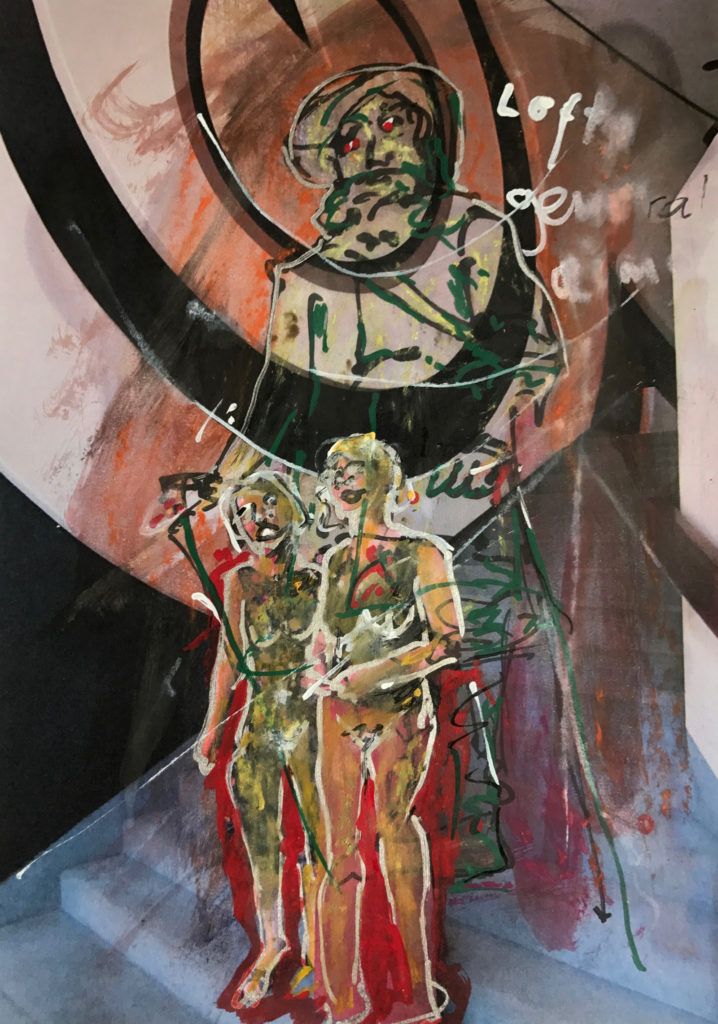

Something that I had observed several times during our journey, that impressed me again at the Metal Garden, was that there were amongst us many artists, painters, musicians and poets. The Maker of Masques was there and the Scribe of Anastasia, the Autumnal One put in an apologetic appearance, seeming only half alive, as did the Venerable Sage from Nieu Bethesda. I remarked to St. Michael, who recited his poem ‘Imagine’ to the animals and the flowers, that artists sometimes appear to be only half-alive, while their creations seem so irrefutably alive. He replied: ‘it is just the same with mothers. When they have borne their children and given them their milk and beauty and strength, they themselves become insignificant and no one asks about them any more.’ The law of service ordains this, added Paul, who was soon to be with us no more. ‘Law?’, I asked. ‘Yes’, he replied, ‘he who wishes to live long must serve, but he who wishes to rule does not live long’.

Thinking back, I recognise this moment as the one that makes narrating the Journey to the South so difficult. In which medium is it possible for the story of the Journey of the South to be told? Instead of a fabric, I hold in my hands a bundle of a thousand knotted threads which would occupy hundreds of hands for years to disentangle and straighten out, even if every thread did not become terribly brittle and break between the fingers as soon as it is handled and gently teased out. I imagine that every historian is similarly affected when he begins to record the events of some period and wishes to portray them sincerely. Where is the centre of events, the common standpoint around which they revolve and which gives them cohesion? In order that something like cohesion, something like causality, that some kind of meaning might be revealed and that it can in some way be told, the historian must invent units, a hero, a nation, an idea, and he must allow to happen to this invented unit what has in reality happened to the nameless. There is no unit, no centre, no point around which the wheel revolves. The doubt created by the events connected to the Gorge of Ēthikē, led not only to the question ‘Can your story be told?’, but also to the more important question, ‘Was it possible to experience it?’

I thought I had experienced events clearly and vividly, I was almost bursting with images of them; the roll of film in my head seemed miles long. But when I sat at my writing-desk, on a chair, at a table, the festivities and celebrations, the sounds from my piano, the courageous perseverance that characterised our journey, were all immeasurably remote, only a dream, were not related to anything and could not really be conceived. Men have perhaps no stronger hunger than to forget. If it is possible for me to write, it is because it is necessary. I either have to write or be reduced to despair; it is the only means of saving me from nothingness, chaos and suicide.

Keeping in mind the fluid interchanges between time and place in The Journey to the South, it is fairly unproblematic to propose that Muller is replacing the geographical location of the Morbio Inferiore with the historical specificity of an event. In other words, for Muller, the dangerous Gorge of Ēthikē is less a place than an event implying a place. It is at the Gorge of Ēthikē where the travellers to the South lose their way and their journey comes to grief. Muller describes it as the culmination of a ‘chain of events through which the eternal enemy sought to bring disaster to our undertaking’ and an ‘intervention’, the consequences of which manifested in loss and the dissolving of the journey. In what follows, I shall attempt to explain the meaning of the plagiaristic character of The Journey to the South, the importance of the Great Change as identifiable historical contextual event and the significance of the historically-veiled events at the Gorge of Ēthikē. I shall do so by invoking Alain Badiou’s Ethics: An Essay on the Understanding of Evil.[7]Alain Badiou, Ethics: An Essay on the Understanding of Evil, tr. and introduced Peter Hallward (London, 2012); French edn., L’éthique: Essai sur la conscience du Mal (Paris, 1993).

Badiou’s text, as he explains in the preface to the English edition, was ‘driven by genuine fury’ at the ‘ethical delirium’ into which the word had been plunged, a ‘mindless catechism’ in which ‘the presumed “rights of man” were serving at every point to annihilate any attempt to invent forms of free thought’.[8]Badiou, Ethics: An Essay on the Understanding of Evil, liii. In his book, he rages against moralism, a generalised victimisation and the ideological consensus – what he calls ‘the ideology of ethics’ – holding these things together. To outline this ideology, Badiou first deconstructs the notion of the universal human Subject, ‘capable of reducing ethical issues to matters of human rights and humanitarian actions’[9]Ibid., 10. as the centre of the contemporary ideology of ethics. At this step in his argument he advances three theses:

Thesis 1: Man is to be identified by his affirmative thought, by the singular truths of which he is capable, by the Immortal which makes of him the most resilient and most paradoxical of animals.

Thesis 2: It is from our positive capability for Good, and thus from our boundary-breaking treatment of possibilities and our refusal of conservatism, including the conservation of being, that we are to identify Evil – not vice versa.

Thesis 3: All humanity has its root in the identification in thought of singular situations. There is no ethics in general. There are only – eventually – ethics of processes by which we treat the possibilities of a situation.[10]Ibid., 16.

To address the counter-argument, namely that ethics is primarily an ethics of the other rather than the self, Badiou moves on to the question: Does the Other exist? Badiou proclaims that, without God, the ethics of the other fails. He then sets out the alternatives: There is no God, and infinite alterity is quite simply what there is.[11]Ibid., 25.

This is, finally, how we are to understand The Journey of the South as a plagiarised text. Plagiarism is the holocaust of academic ethics, the exemplary radical negative evil, the Altogether-Evil of the ideology of ethical transgression as it manifests in writing. In presenting a plagiarised text as a non-forgetting of truth processes ignited by encounters with events, Muller is refusing to acknowledge the primary, religious character of Evil. Evil, he seems to be saying, needs to be situated as part of a political sequence that includes the Great Change and the interventions at the Gorge of Ēthikē. What is evil cannot be understood on the level of general ethics, but only an ethic of the work to be done in the wake of the devastation wreaked by apartheid. Plagiarism, understood in this way in this particular manifestation, becomes an encounter with the courage of the Good at the same time as if poses an affront to ideas of an a priori or primary category of Evil predicated on variations of ancient religious and moral preaching and a threatening mix of conservatism.

The events of the Great Change and the interventions at the Gorge of Ēthikē are not only calls to truth processes, but invitations for Evil to manifest itself in the simulacrum and terror, in betrayal and in the disaster of total power. Whether this evil resides in the transgression of the consensus characterising the ideology of ethics, or whether it resides in the impotent morality refusing to engage with events as constitutive of truth processes, is the question we are left with.

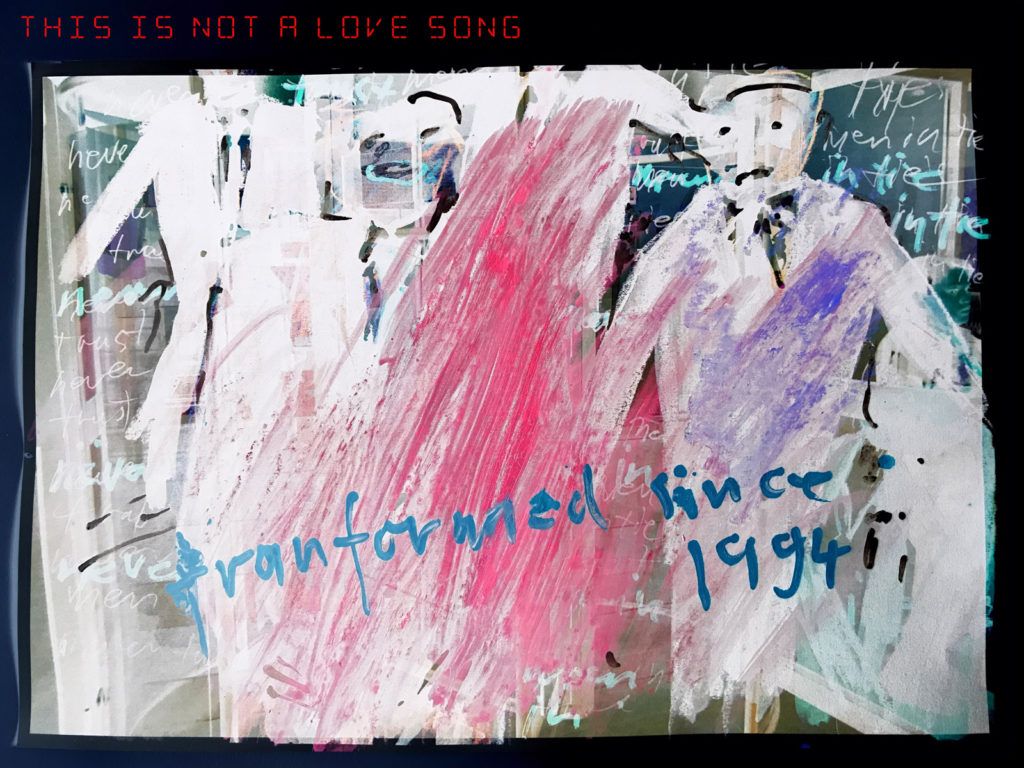

The Journey to the South is a parable about methodology. More specifically, it is a piece of writing that suggests, performatively as well as constitutively, a break

between two ways of doing things rather than two kinds of things per se. To be sure, it is about the difficulty of writing about The Journey to the South, wherever and whatever that may be. But the text also contains abstract speculations about ways of reaching goals, be they Karoo dances or peculiar southern gardens. In short then: a riddle about the how of artistic and scholarly discovery.

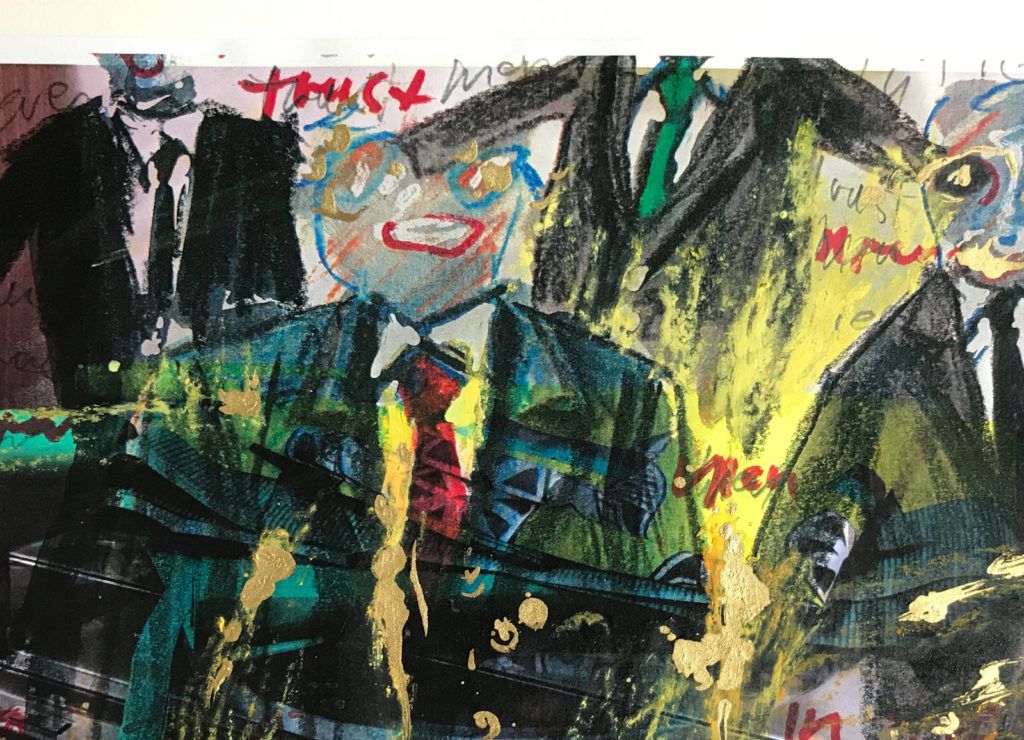

Many commentators have remarked on the clear historical significance of the Great Change to Muller. His obsessive-compulsive scholarly return to apartheid as paradigmatic to all thought on culture in South Africa is well known. Some have called this dogged pursuit the opportunism of the untalented; others the tormented cravings of a guilty conscience; and yet others the desire to perpetuate whiteness by keeping apartheid central to our understandings of all things. Some have even said that it illustrates the slow succumbing of the mind to the tragic madness of apartheid and post-apartheid thought. The journey (in itself a method to accomplish ‘lofty general aims’), takes place in a South Africa filled to the brim with ‘saviours, prophets and disciples’. This is a place of ‘many chimeras’, but also of education mindful of the past (the canon, we read, ‘was taught to the ignorant wherever we went’ and the pilgrims ‘honoured structures and institutions’). The activities of those embarked on the journey are made subject to institutional discipline: ‘vows of secrecy, strict codes of conduct adopted in Singapore’ and ‘threats from the Guardians of the Colloquium’.

The clearest indication that this parable has methodology as a primary concern, occurs in the text following the description of the intervention at the Gorge of Ēthikē. The specificity of this name does not concern us here – I suspect it is nothing but a superficial and opportunistic reference to Greek erudition – but the effects of the intervention are important: loss, deprivation, unreliability, doubt, the breakdown of meaning. All things, I would like to argue, that point to a methodological crisis latent in the events after the Great Change and made explicit by the interventions at the Gorge of Ēthikē.

The travellers in The Journey to the South engage in a series of activities that suggest four post-Great Change methodological propositions that, following the work of Jacques Rancière, I will classify as play, inventory, encounter and mystery.[12]These categories appear in Rancière’s chapter ‘Problems and Transformations of Critical Art’ in Aesthetics and its Discontents, 45-60 and esp. 53-58. As the name of the chapter suggests, Rancière’s concern here is not with scholarship and methodology, but how aesthetics and politics are linked in and through art. By adopting his categories as methodological propositions for scholarship, I am already suggesting a larger methodological premise, namely the linking of scholarship about art and art; a move that allows the former to borrow from the latter political energies of refusal while not sacrificing its connection to meaning.

All four of these methodological propositions – play, inventory, encounter and mystery – are demonstrated in the parable, which is in turn a détournement of a Hesse text, an inventory of people and projects, an encounter at the Gorge of Ēthikē and a veiled (one might say, mysterious) message that ‘testifies to co-presence’ of time and space. Thus the parable, to an extent, performs a methodology rather than explicating it. One might say that the parable in itself critiques the limitations of methodology as a system of methods used in a particular area of study through insinuating that what is readily thought of as a ‘particular area of study’ (for instance music) is infinitely more complex than hitherto believed and therefore elicits methodological approaches that acknowledge this complexity. In what follows I shall present these methodological propositions as they occur in the parable, keeping in mind that the parable already performs these propositions in an integrated way.

Play is not only a way of becoming fully human qua Schiller’s free man, but a way of mobilising a thick present of contemporaneity; not to understand as such, but to sharpen perceptions and awareness in the domain of the undecidable.

The second methodological proposition, ‘inventory’, seems to function as the opposite of what the parable calls ‘forgetting, suppressing and concealing’. Not only is the narrator of the parable a collector of ‘old songs and writings’, implying the activity primary to the constitution of the inventory, but the list of personages and projects presented in the parable constitutes an inventory.

The inventory becomes a way of suggesting a new kind of community by refusing to acknowledge the fragmentation

imposed on us by hyper-specialisation as a prerequisite for disciplinary integrity. If the pseudo-science of apartheid was the science of the category and taxonomic classification in which every element had its place and could, therefore, be controlled and instrumentalised, the inventory suggests a move away from the elements towards a new perspective on the relationships

between these elements.

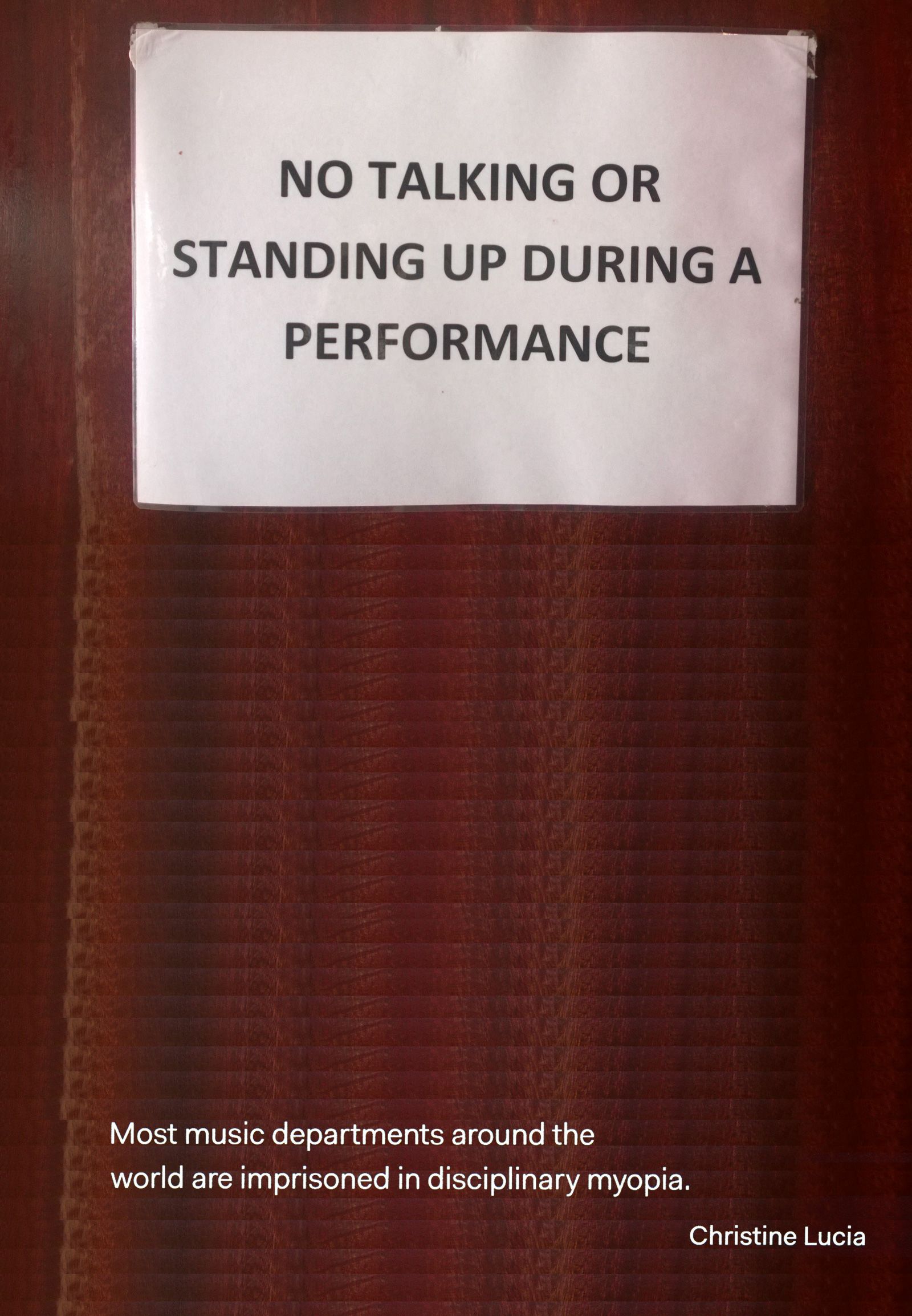

Filtered down to the level where we write about music, this dissociation, this suspended condition of ‘distance from’ and ‘proximity to’ finds expression in the most rigorous separation that echoes, in its disciplinary incarnations of the Boer state (as Nick Land calls it), the divisions of our discipline and curricula, the infantile assertions of music’s specificity (which confirm, if anything, that music as practised in our concert halls is a non-art), the desultory record of musicology that has produced countless imitations and emulations of the very unreality of the separated reality it so happily contributed to construct, the fatal isolation of music from any kind of energy other than that needed to make it aspire to the art-for-art’s sake ideology that guarantees its status as non-art today.

Radical encounter in art (and hence also music), writes Jesús Sepúlveda, means

to remove art from the sphere of the institution [and] living art in life and vice versa. It means destroying the alienation that implies distinction between the artistic and intellectual, and the vulgar and manual. It means beautifying life and enlivening art, both as a unified and organic whole. It also means creating a humanity of artists, and humanizing the artists who already exist.[13]Jesús Sepúlveda, The Garden of Peculiarities, tr. Daniel Montero (Cape Town, 2013), 39. Spanish edn., El jardin de las peculiaridades (Buenos Aires, 2002).

Rather than hypothetically asking, therefore, if interdisciplinarity is enough, the more urgent question in the light of this history and imperative is surely ‘Is interdisciplinarity/transdisciplinarity optional?’[14]See Martina Viljoen’s article ‘Is Interdisciplinarity Enough? Critical Remarks on Some “New Musicological” Strategies from the Perspective of the Thought of Christopher Norris’ in International Review of the Aesthetics and Sociology of Music 43:1 (2012), 71-94. Keeping with the facts of a reality assumptive of a consensus is only possible in bantustans of the mind governed from seventeenth-century capitals of knowledge domination.

The last methodological proposition contained in The Journey to the South is ‘mystery’. Explicating ‘mystery’ is no doubt counterproductive, but I suspect that mystery has real implications for the formal structure of academic disputation and the language in which that disputation takes place. ‘Words’, writes Sepúlveda, ‘can be serious – and also magical – because they concentrate the energy that permits the movement of the world …’[15]Sepúlveda, The Garden of Peculiarities, 92.

These themes should provoke prolonged methodological discussion. Apartheid promulgated a methodology, consisted of a methodology, inculcated a methodology systematically through all its structures (universities and their constituent disciplines included). This is at the same time completely obvious and likely to enrage the practitioners of such methodologies who have been allowed by what Sampie Terblanche calls the ‘1994 elite conspiracy’ to continue unabated and unapologetically with their work.

It is obvious in the same way that the Holocaust was a rational operation in the planning and execution thereof and therefore an exemplary instance of methodological rigour. It invites outrage because this rigour always has to remain separate from historical cause and effect (which cannot explain the very activity itself) and therefore is pushed beyond what it can comprehend of itself by the connector ‘apartheid methodology’. The Journey to the South challenges us to make this very connection.

The Journey to the South is a parable about aesthetics. More so, it is about music aesthetics. Everywhere in the text, the writing strains to declare an aesthetic position, which is superficially, intriguingly, made subject to what Jacques Rancière calls ‘an ethical turn’ (about which more later).[16]Rancière, Aesthetics and its Discontents, 114. I offer only a few examples to illustrate the centrality of musical aesthetics in the parable.

The common and individual goals of the travellers concern art (predominantly music), but do so in a way that confirms art’s difficulties for Western philosophy after Kant as a catastrophe[17]Nick Land’s formulation. See ‘Art as Insurrection: the Question of Aesthetics in Kant, Schopenhauer, and Nietzsche’ in Fanged Noumena, 145-174, esp. 145.

in a landscape marked, appropriately, by apocalypse.

In an artistic community (‘there were amongst us many artists, painters, musicians and poets’) that has embarked on a journey and is therefore distinctly mobile[18]This is significant. As Sepúlveda writes: ‘Immobility […] pays homage to repression. Only movement liberates.’ See The Garden of Peculiarities, 83. – and I think we can read here a move away from stagnant theism – the art concerned is marked by the excess of ‘good humour … songs … invention … enthusiasm for chance and the hazardous’ as well as ‘the endless interruptions

in the name of redress … idleness … childish wanderings in speculative thought … endless conversations … the attaching of importance to magic … the intermingling of life and history and poetry’. This, one is told, stands in opposition to ‘common-sense and useful work’, the ‘blindness of reason, faint-heartedness, weariness and disillusionment’. Muller’s parable even gives examples of these different kinds of art. On the one hand, the tending of a garden of peculiarities unique to the South, dances under the stars with drilling machines in the Karoo, discoveries of the secrets of the founding muses in obscure music and enwindment of landscapes of desolation. On the other side of the spectrum: ‘ritual performances of necromancy, scrolls celebrating the achievements of minnows, the burgeoning of bureaucracies conceived to design, legitimate and enforce the proper ways of addressing the apocalypse we could see around us.’ The latter is not a work of art as such, but more of a description of an apparatus of control aimed at standardisation and domestication of expression, otherwise known as censorship.

The most glaring aesthetic statement of Muller’s text is not what is written about in the text (although the content is clearly aimed at encouraging an engagement with aesthetics) but the way the text reflects on the problems of its own construction. Muller writes:

In which medium is it possible for the story of The Journey of the South to be told? Instead of a fabric, I hold in my hands a bundle of a thousand knotted threads which would occupy hundreds of hands for years to disentangle and straighten out, even if every thread did not become terribly brittle and break between the fingers as soon as it is handled and gently teased out.

There is a problem here, as this passage is taken almost verbatim from Hermann Hesse’s rather mysterious and little-known novel, The Journey to the East.[19]See Hermann Hesse, The Journey to the East, 62. Although it is the narrator who is speaking here, is it Muller writing this text, or Hesse?

And is it Muller’s narrator or Hesse’s narrator who is speaking? At stake here is the matter of authorship and agency as an unspecified distribution of voices and, not unrelated, the matter of scholarly ethics, already referred to in the introduction to this critique through Rancière’s phrase ‘the ethical turn’. The ethical implication of what I regard as an engagement with aesthetics in this palimpsestic text is important to keep in mind in what follows, as I will return to it towards the end of the critique.

Returning to the paragraph cited above, I wish to spend time considering the metaphor of the knot, and in particular how the knot relates to aesthetics in a way that makes a discussion on music (if not exactly ‘the music itself’) possible in our times. In his set of essays, Aesthetics and its Discontents, Jacques Rancière writes as follows:

If ‘aesthetics’ is the name of a confusion, this ‘confusion’ is nevertheless one that permits us to identify what pertains to art, i.e. its objects, modes of experience and forms of thought – the very things we profess to be isolating by denouncing aesthetics. By undoing this knot so that we can better discern practices of art or aesthetic effects in their singularity, we are thus perhaps fated to missing that very singularity.[20]Rancière, Aesthetics and its Discontents, 4. Elsewhere he writes that ‘aesthetics is the word that expresses the singular knot that, posing a problem for thought, formed two centuries ago …’; Ibid., 14. This follows the ‘undoing’ of another knot, the one that had defined the representational regime: ‘this knot had tied together a productive nature [poiesis], a sensible nature [aisthesis] and a legislative nature called mimesis or representation’; Ibid., 7. ‘Aesthetics’, Rancière continues, ‘is above all the discourse that announces this break with the threefold relation enshrining the order of fine arts.’; Ibid.,

In this formulation, we are presented with the notion of aesthetics as a knot. It is certainly not, for Rancière, the dirty word that Pierre Bourdieu so memorably described as the site of the ‘denigration of the social’ thirty years ago,[21]The most important source here is Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste, tr. Richard Nice (Boston, 1984); French edn., La Distinction: Critique sociale du jugement (Paris, 1979). nor is it the corruption of art as event that Badiou tries to circumvent with his term ‘inaesthetics’.[22] See Alain Badiou, Handbook of Inaesthetics, tr. Alberto Toscano (Stanford, 2005); French edn., Petit manuel d’inesthetique (Paris, 1998). Rancière sees aesthetics not as a by-product of philosophy or a theory, but as a regime of art that succeeds the representational regime of art[23]Effectively this is the Aristotelian approach: ‘a regime in which art does not exist as the name of a specific domain, but in which there exist specific criteria of identification, concerning what it is that the arts make and the appreciation of how it is done, whether good or bad’; Aesthetics and its Discontents, 65. at the same time that music becomes the most prominent way to articulate, in his words, ‘a relation without mediation between the calculus of the work and the pure sensible effect, which is also an immediate relation between the technical device and the song of inner life’.[24]Ibid., 7. The aesthetic regime of art is characterised by a poiesis (way of doing) and aisthesis (way of being that is affected by the way of doing) that stand in immediate relation to each other and that can only ‘be brought to agree by a human nature that is either lost or by a humanity to come’. Muller’s metaphor of a journey implies both the lost human nature (the events preceding the Great Change) and the anticipated humanity to come (presumably the outcome of the journey). In acknowledging that aesthetics poses a problem for thought, a knot constituted of the ‘functioning of art and a matrix of discourse’,[25]Ibid., 14. an engagement with the ‘paradoxical sensorium’ that makes it possible to define the things of art,[26]‘This sensorium,’ writes Rancière, ‘is that of a lost human nature, which is to say of a lost norm of adequation between an active faculty and a receptive faculty. What has come to replace this lost norm of adequation is an immediate union: the concept-less union of the opposition between pure, voluntary activity and pure passivity.’; Ibid., 11-12 Rancière wants to show how ‘aesthetics, as a regime for identifying art, carries a politics, or metapolitics, within it’.[27]Ibid., 14-15. It is this insight of the knot as terrain for aesthetics as politics and politics as aesthetics, that I think Muller is problematising in The Journey to the South.

I will resist the temptation to read into Muller’s oppositional formula of artistic manifestations in his parable a postmodern rupture that validates music’s radicalism in its anarchic qualities as opposed to its rational conceits. The aesthetic regime of art outlined by Rancière puts a lie to such childishness by recognising that the power of music inheres both in its distance with respect to ordinary experience (autonomy) and the relational aesthetics that claims to reject music’s self-sufficiency (heteronomy). Aesthetics as the ‘knot’ where we negotiate the meaning of art, and specifically music, has its own politics (or meta-politics if music’s own politics are taken into account) that has less to do with what is really a defunct debate on musical autonomy and the functionary value of a phrase like ‘the music itself’, and more to do with ‘reconfiguring the distribution of the sensible’ so that new subjects and objects are rendered audible. It is here where critical musicology and critique should be located, not as a politicised discourse, but as a fundamentally aesthetic discourse. It is also here where authoritarianism, institutional power, censorship and intimidation should be confronted, not under the banner of scholarly ethics, but in the name of aesthetics.

The Journey to the South makes these matters the centre of both the goals of humanity and the things humans do. Any discourse on music that imagines the antinomies of modernism to be of concern to us in South Africa today, as Muller seems to do, is to my mind mistaken. But even more misguided is his suggestion that music after the Great Change is, to use Rancière’s expression, ‘an endless work of mourning’,[28]Ibid., 130. whether it be the music of work or of play. Embedded in our thick present of contemporaneous events flowing at different rhythms, the knot of the aesthetic is a collection of threads characterised by an ‘almost’ that anticipates the futures we dream of or fear.

The Journey to the South is a parable about institutions. The reference in the parable to a ‘burgeoning of bureaucracies conceived to design, legitimate and enforce the proper ways of addressing the apocalypse’, makes this clear enough, as does the way in which the travellers visit and honour structures and institutions on their journey. The Guardians of the Colloquium, invested with the legitimacy of the Curse of Singapore,[29]An unambiguous reference to the Singapore Statement on Research Integrity, ‘the product of the collective effort and insights of the 340 individuals from 51 countries who participated in the 2nd World Conference on Research Integrity’; see http://www.singaporestatement.org. The statement was adopted ‘for global use’ on 22 September 2010. as well as the information proffered in the parable that these guardians control borders, is a further reminder that whatever else happens in the parable, happens within a context of institutional power.

Muller has worked as musicologist and founder and director of the Documentation Centre for Music (DOMUS) at the University of Stellenbosch since 2005, where he has been instrumental in perpetuating Afrikaner power through the training and instrumentalising of cohorts of so-called white students who then go forth to people the academic community like cancerous cells attacking the health of the body musical.[30]These are serious allegations which, to be sure, are not my own. Both the charges of ‘instrumentalisation’ and the description of Muller’s students as ‘cancerous cells’ are descriptions of whistleblowers who prefer to remain anonymous. Their rights are protected by the Singapore Statement, which states in clause 12 the responsibility to ‘protecting those who report such behavior in good faith’. Their faith is nothing if not good. He is both deeply embedded in academic institutionalism and pathologically, narcissistically dedicated to its destruction through projects deeply inimical and dangerous to the discipline of musicology and to the survival (I choose this word advisedly) of Western art music at our tertiary institutions. Possibly unaware of the damage he inadvertently causes, he is a member of the vanguard of a cultural police that has released terrorist

(mostly ineffectual) disapproval on some of the most esteemed artists that have crossed his path.

Muller has been critical of the way in which old apartheid universities have ‘transformed’ from volksuniversiteite and more liberal English universities to the paragons of enlightenment they claim to be. Yet, hypocritically, he has continued to work (and advance) in one of these very institutions.

In his article, Muller takes this statement as an exemplary instance of what he calls ‘at least an attempt to articulate the disaster from which South African university education has had to recover’.[31]Muller, ‘Die Antwoord’, 666. Citing the report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, he notes that no South African universities made submissions to the commission, very few academics or artists did so in their personal capacities or collaborated with the commission in any way, and then goes on to argue that universities such as his own have not had to change so much as recode the historical mechanisms of hierarchy and power in order to function successfully after 1994 in South Africa. Singling out the structures charged with repairing the moral fibre of universities historically instrumental in intellectualising what the United Nations has called ‘a crime against humanity’ (apartheid), Muller alleges that most such structures have, in their wholesale adoption of international ethics frameworks indiscriminately applied to a range of disciplines, taken no cognisance of the effects of the ideology of ethics on institutions where the humanities are emerging from decades of censorship and politically acquiescent scholarship. Although he provides no proof for this, he continues to allege that it stands to reason that if apartheid-era academics had continued to staff the institutions after political regime-change in 1994, there would be no reason to expect them to adopt a different scholarly ethic to the one they had internalised in order to function in the repressive structures in which they had been intellectually nurtured and rewarded. Thus, he concludes, ‘ethics now’ is best described as ‘ethics then’ with the political stink removed.[32]Ibid., 666.

All of this is, of course, a gross and quite possibly litigious insult to the integrity of those scholars and administrators who subscribe to vision and mission statements from university to faculty to departmental levels that state exactly the opposite, namely a commitment to transforming our institutions after the end of apartheid. Let me set the record straight. My own university embraces transformation at all levels. Like Derrida, we recognise that traditional law should provide the support towards a new foundational place. Muller’s parable, like much of his other writing and activities, is a reprehensible smear of the integrity of departments like these who have pulled South African musical culture by the bootstraps into the twenty-first century. In short, while not all South African universities have made sweeping and self-castigating pronouncements about their past conducts under apartheid, some of them have been getting on with the job of creating a better future.

Commissar A: I read The Journey to the South and it is a parable about shit. No doubt about it.

Dispositif 1: I can see you.

Shadowy Figure 1 passes Shadowy Figure 2 a piece of paper.

Shadowy Figure 2 (reading): I ask you, colleagues, to maintain a degree of civility. If we must discuss this – and I regard it as my duty to tell you that I have serious qualms about the intellectual and artistic premises of this discussion – then please let us (a) use the words ‘faecal matter’, (b) refrain from ad hominem remarks and (c) stick to the matter at hand, namely a critique of the text The Journey to the South.

Dispositif 2: And keep it apolitical, please, for all our sakes.

Shadowy Figure 1 passes Shadowy Figure 2 a piece of paper.

Shadowy figure 2 (reading): Colleagues, colleagues, I suggest we agree on the agenda: a discussion of The Journey to the South. What does faecal matter have to do with this text? I see no reference to it in the text, and therefore I would hold it is of no relevance to the text. The statement by Commissar A that ‘The Journey to the South […] is a parable about shit’, is therefore not correct. The statement by Commissar A that he is invisible, is not correct. I can see him …

Dispositif 1: Ahem.

Shadowy figure 2 (continues): … The statement that all so-called invisible men defecate in public, is not correct. I never see people defecate in public, whether they be visible or invisible. The synonyms of faecal matter, are irrelevant and in bad taste.

Commissar A (takes no notice): Shit has a history, and it is embedded in Muller’s parable even if he doesn’t know it. In fact, it is embedded in Muller’s parable because he doesn’t know it. Between all the dreaming and travelling and poetry and art and ‘lofty general aims’ and ‘real spiritual advances’ and ‘hope’ and ‘amazing phenomena’ and ‘beautiful experiences’, what do you think these people do? I’ll tell you, they shit! But they shit in private. Muller’s world, the world of visible people, is a world of private shitting. It is only in the invisible world where people shit in public.

Dispositif 2: This sounds like the clear, accurate facts have been politicised. I cannot see how these allegations are conclusions based on the critical analysis of the evidence …

Dispositif 1: … nor how the interpretations are comprehensive or objective.

Trictrac: Commissar A has a point, though. Since Vespasian Africans have been throwing things at authority, and poor Marcus Bibulus became a monument of excrement when he tried to deny the poor. Does anyone remember the Dirt Protest by the Irish Republican Army in Long Kesh prison in the 1970s?.[33]Trictrac has taken these sentiments, mostly verbatim, from Rustum Kozain’s excellent article ‘A Brief History of Throwing Shit’ in Chimurenga Chronic, November 2013, 3.

Dispositif 1 (to Dispositif 2): Check the facts. Note the last sentence as possibly irresponsible and careless for an urgent report to the appropriate authorities.

Shadowy figure 2 (shaking his head): Could we please agree to use the word ‘defecate’, spelt: d-e-f-e-c-a-t-e.

Commissar A: (continues): Contemplate the insulting paragraph about the celebration in the Metal Garden. I read it aloud:

(takes a piece of paper, melodramatically stands up and reads like a pseudo parliamentarian in a pseudo accent)

Outside, people squatted in their shacks, enchanted by the beauty of the evening. It was one of the triumphant periods of our journey; we had brought the magic wave with us; it cleansed everything. The shack dwellers knelt and worshipped beauty.

Contrast this to the press statement by Abahlali baseMjondolo (the Shack Dwellers Movement) that says ‘We live in shit and fire’.

Shadowy figure 2: The statement ‘drowning in shit’ is not correct. Newspaper reports confirm that there were no drownings on that day. The statement ‘squatters on the doorstep’ is incorrect. The Metal Garden has no doorstep. Therefore, no one can live on the doorstep. Therefore, Commissar A’s outrage derives from not knowing all the facts and not being properly informed.

Shadowy figure 2 (clears his throat): In Rabelais’s Gargantua and Pantagruel, the birth of Gargantua is confused with his mother’s bowel movement after she has gorged herself on tripe: birth and decay, life and defecation. Gargantua soon learns to defecate in private and impresses his father, who considers this development as a sign of the divine in his child. The child has grown up.[34]Shadow Figure 2 is citing from Rustum Kozain, ‘A Brief History of Throwing Shit’, 3. I put it to you that we must keep certain things private as a sign of our maturity, in order to maintain the decorum of our society. Certain things do not belong in the public domain.

Dispositif 2: Good point, I will make a note.

Commissar A: Your Singapore Statement is a gilded turd.

Trictrac: Now-now, A, calm down. Number 2 has the right to reply and being Number 2, his replies are usually substantial. I also know a lady in Singapore and she is actually a very nice person. I’ll say this, and if you’ll allow me the digression from my recognised expertise (which is diarrhoea), I would venture to say that the desire to hide excrement, to disavow it, i.e. to do it in private, worry about its smell, flush it away or bury it, is to enter capitalism as a productive subject in which the body is repressed. We wash, as Number 1 so wisely advises, we deodorise and wear clean clothes. The clinical must prevail over the excessive if we are to communicate with each other.[35]Trictrac uses the ideas from Rustum Kozain, ‘A Brief History of Throwing Shit’, 3.

Commissar A: And what happens when we treat humans like shit? In this, the most industrialised country on the African continent, the economy is the sewage system of the human abject. For some of us, I have to add. The slave trade was a massive sewage system of humans not treated like shit, but humans treated as shit. The post-1994 (Great Change my arse) economy continues where the slave trade left off. A surplus people are trucked and taxied into cities for their labour and expelled in the evenings.[36]Ibid.

Dead-German-philosopher-who-never-arrives-and-leaves-unexpectedly: Love only that which you have always believed! (leaves in a huff)

Shadowy figure 1 scribbles furiously: ‘unprecedented successes, international recognition, hard work, exceptional talent, artistic excellence, selling ourselves, WE ARE EXCEPTIONS’ and passes the note to Shadowy figure 2, who looks at it, swears and throws it into his handbag.

Number 2: Mmmmm …. Number 1 is innocent. The inappropriate introduction of the confidentiality of the private domain into the public domain is an attack on the whole academic community. It transgresses the Singapore Statement in that it is not indicative of professional courtesy and fairness in working with others. It is also a health hazard.

Dispositif 1 (coming to): Amen to that!

Chorus: (unperturbed, in spoken chorus)

We are so sorry.

Sorry, sorry, sorry.

Commissar A (pulls off his trousers): I’ve had enough of this shit. Time for the real thing …

THE REST OF THIS CRITIQUE HAS BEEN BLACKENED OUT TO PREVENT IDENTIFICATION OF THE REAL THING AS THE REAL THING CAN PUT ANY NUMBER OF INDIVIDUALS AND INSTITUTIONS AT RISK OF DISCOVERING THE REAL THING.

Stephanus Muller

Lockdowneville, April 2020

The unabridged and original version of this text was first published as The Journey to the South by African SunMedia, Stellenbosch, in 2019. This précis is published with permission.

| 1. | ↑ | I adapt the line of reasoning in this paragraph from Bill Readings’s book, The University in Ruins (Cambridge, Mass., 1996), where he writes not about music, but about the role of the English literary canon in North American universities. |

| 2. | ↑ | Ibid., 35. |

| 3. | ↑ | Sharné Nieuwoudt, Kasha Elizabeth Dickie, Carla Coetsee, Louise Engelbrecht and Elmarie Terblanche, ‘Age- and Education-related Effects on Cognitive Functioning in Colored South African Women’, Aging, Neuropsychology, and Cognition (2 May 2019). |

| 4. | ↑ | For discussions and reactions to the article by Stellenbosch University, see [accessed 1 September 2019]. |

| 5. | ↑ | See Roland Barthes, The Neutral: Lecture Course at the Collège de France (1977-1978), texts established, annotated and presented by Thomas Clertc under direction of Eric Marty, tr. Rosalind E. Krauss and Denis Hollier (New York, 2005). I should like to thank Christine Lucia for pointing me to this text. |

| 6. | ↑ | Ibid., 81. |

| 7. | ↑ | Alain Badiou, Ethics: An Essay on the Understanding of Evil, tr. and introduced Peter Hallward (London, 2012); French edn., L’éthique: Essai sur la conscience du Mal (Paris, 1993). |

| 8. | ↑ | Badiou, Ethics: An Essay on the Understanding of Evil, liii. |

| 9. | ↑ | Ibid., 10. |

| 10. | ↑ | Ibid., 16. |

| 11. | ↑ | Ibid., 25. |

| 12. | ↑ | These categories appear in Rancière’s chapter ‘Problems and Transformations of Critical Art’ in Aesthetics and its Discontents, 45-60 and esp. 53-58. As the name of the chapter suggests, Rancière’s concern here is not with scholarship and methodology, but how aesthetics and politics are linked in and through art. By adopting his categories as methodological propositions for scholarship, I am already suggesting a larger methodological premise, namely the linking of scholarship about art and art; a move that allows the former to borrow from the latter political energies of refusal while not sacrificing its connection to meaning. |

| 13. | ↑ | Jesús Sepúlveda, The Garden of Peculiarities, tr. Daniel Montero (Cape Town, 2013), 39. Spanish edn., El jardin de las peculiaridades (Buenos Aires, 2002). |

| 14. | ↑ | See Martina Viljoen’s article ‘Is Interdisciplinarity Enough? Critical Remarks on Some “New Musicological” Strategies from the Perspective of the Thought of Christopher Norris’ in International Review of the Aesthetics and Sociology of Music 43:1 (2012), 71-94. |

| 15. | ↑ | Sepúlveda, The Garden of Peculiarities, 92. |

| 16. | ↑ | Rancière, Aesthetics and its Discontents, 114. |

| 17. | ↑ | Nick Land’s formulation. See ‘Art as Insurrection: the Question of Aesthetics in Kant, Schopenhauer, and Nietzsche’ in Fanged Noumena, 145-174, esp. 145. |

| 18. | ↑ | This is significant. As Sepúlveda writes: ‘Immobility […] pays homage to repression. Only movement liberates.’ See The Garden of Peculiarities, 83. |

| 19. | ↑ | See Hermann Hesse, The Journey to the East, 62. |

| 20. | ↑ | Rancière, Aesthetics and its Discontents, 4. Elsewhere he writes that ‘aesthetics is the word that expresses the singular knot that, posing a problem for thought, formed two centuries ago …’; Ibid., 14. This follows the ‘undoing’ of another knot, the one that had defined the representational regime: ‘this knot had tied together a productive nature [poiesis], a sensible nature [aisthesis] and a legislative nature called mimesis or representation’; Ibid., 7. ‘Aesthetics’, Rancière continues, ‘is above all the discourse that announces this break with the threefold relation enshrining the order of fine arts.’; Ibid., |

| 21. | ↑ | The most important source here is Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste, tr. Richard Nice (Boston, 1984); French edn., La Distinction: Critique sociale du jugement (Paris, 1979). |

| 22. | ↑ | See Alain Badiou, Handbook of Inaesthetics, tr. Alberto Toscano (Stanford, 2005); French edn., Petit manuel d’inesthetique (Paris, 1998). |

| 23. | ↑ | Effectively this is the Aristotelian approach: ‘a regime in which art does not exist as the name of a specific domain, but in which there exist specific criteria of identification, concerning what it is that the arts make and the appreciation of how it is done, whether good or bad’; Aesthetics and its Discontents, 65. |

| 24. | ↑ | Ibid., 7. |

| 25. | ↑ | Ibid., 14. |

| 26. | ↑ | ‘This sensorium,’ writes Rancière, ‘is that of a lost human nature, which is to say of a lost norm of adequation between an active faculty and a receptive faculty. What has come to replace this lost norm of adequation is an immediate union: the concept-less union of the opposition between pure, voluntary activity and pure passivity.’; Ibid., 11-12 |

| 27. | ↑ | Ibid., 14-15. |

| 28. | ↑ | Ibid., 130. |

| 29. | ↑ | An unambiguous reference to the Singapore Statement on Research Integrity, ‘the product of the collective effort and insights of the 340 individuals from 51 countries who participated in the 2nd World Conference on Research Integrity’; see http://www.singaporestatement.org. The statement was adopted ‘for global use’ on 22 September 2010. |

| 30. | ↑ | These are serious allegations which, to be sure, are not my own. Both the charges of ‘instrumentalisation’ and the description of Muller’s students as ‘cancerous cells’ are descriptions of whistleblowers who prefer to remain anonymous. Their rights are protected by the Singapore Statement, which states in clause 12 the responsibility to ‘protecting those who report such behavior in good faith’. Their faith is nothing if not good. |

| 31. | ↑ | Muller, ‘Die Antwoord’, 666. |

| 32. | ↑ | Ibid., 666. |

| 33. | ↑ | Trictrac has taken these sentiments, mostly verbatim, from Rustum Kozain’s excellent article ‘A Brief History of Throwing Shit’ in Chimurenga Chronic, November 2013, 3. |

| 34. | ↑ | Shadow Figure 2 is citing from Rustum Kozain, ‘A Brief History of Throwing Shit’, 3. |

| 35. | ↑ | Trictrac uses the ideas from Rustum Kozain, ‘A Brief History of Throwing Shit’, 3. |

| 36. | ↑ | Ibid. |