LWAZI SIYABONGA LUSHABA

Decolonising Jesus: A Journey into the White Colonial Unconscious

One is unable to think decolonisation through outside of colonialism. Which is to say decolonisation is contingent. It is contingent upon the primary act of a violent imposition upon the indigenous African people, considered less than human, of European rule and its attendant culture, epistemology, religion and cosmology, by a race self-constituted into an exemplary figure of the human qua human subject. To be exact the relationship between colonialism and decolonisation is not sequential. But rather colonialism carries within itself its own refusal, as a complex it becomes whole in the presence and actualization of its own negation, which opens the door onto revolt and liberation. For all of this to make sense demands that we encounter colonialism as something larger than political and economic domination. It calls for the elevation of the experience of political domination to be thought through – how colonialism expresses itself as a set of ideas, how knowledge is simultaneously constitutive and expressive of a set of relations, symptomatic of the asymmetry between the white colonizer and the black colonized. In the historiography of colonialism two orders of knowledge have been key in the constitution of colonial relations; religion and modern western rational science (Majeke; 1986).

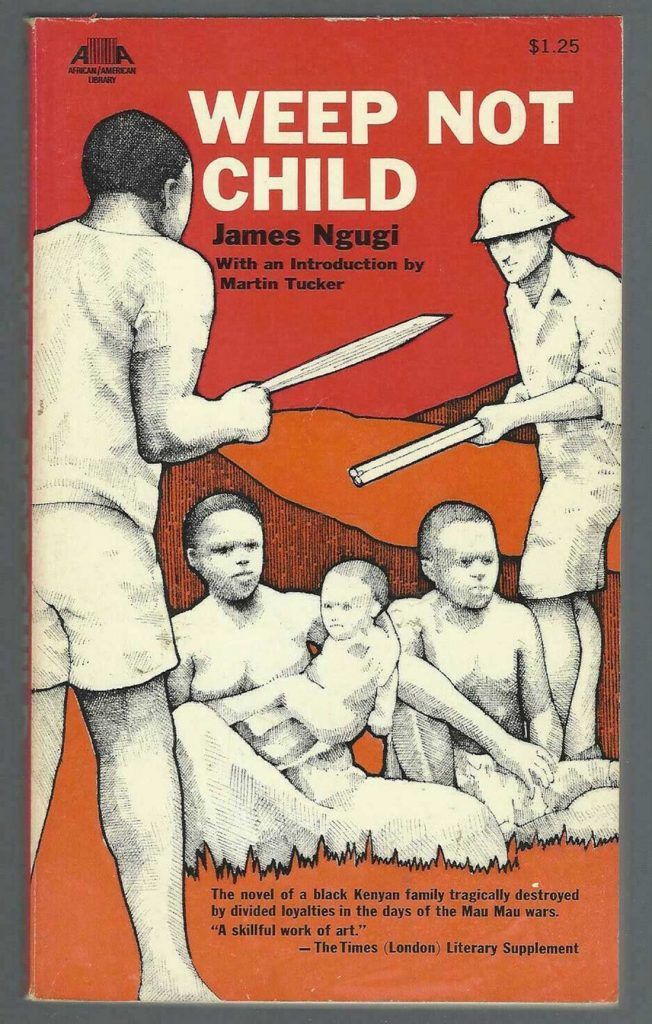

Unsurprisingly, in narrations of the experience and reality of colonialism, African writers direct a telling look toward religion. In Ngugi’s (1964) Weep Not, Child we read of Njoroge’s teacher Isaka who despite his firm religious protestation before a colonial military officer accusing him to be Mau Mau that Jesus had saved him and he thus could not exchange Jesus with Mau Mau, is mocked it would seem by Jesus himself; ‘[C]ome this way and we’ll see what Jesus will do for you’ (1964:101). Those words uttered with utmost contempt – often reserved for the black colonized – turned out to be last he heard whilst alive. He was summarily executed – military style – a moment later. In Chinua Achebe’s (1957) classic, Things Fall Apart, Okonkwo, son of Unoka, laments bitterly the deleterious effects of European religion on African modes of being. On noticing the societal disintegration of his community of Umuofia on account of the arrival and activities of the white colonial missionaries, Okonkwo, with sagacity typical of the age, remarks to his friend Obierika; “Does the white man understand our custom? How can he when he does not even speak our tongue?” answers Obierika. “But he says our customs are bad; and our own brothers who have taken up his religion also say that our customs are bad…Now he has won our brothers, and our clan can no longer act like one. He has put a knife on the things that held us together and we have fallen apart” (1957: 155-156). What the two texts above are symptomatic of is a much wider presence of religion in African narrations of the colonial experience. Without exception all these writings foreground the complicity of religion and religious ideology in the functioning, reproduction, and profitability of the colonial enterprise (see Majeke; 1986, Mphahlele; 1959).

It is thus not coincidental that everywhere in the continent the nationalist struggle for liberation organised itself around two focal points – the epistemic and the political – with religion neatly folded into the epistemic or as part of epistemic domination. The attainment of formal independence in the 1960s by colonies of domination meant the defeat of colonialism read as political domination, partial decolonisation if you prefer.[1]Colonialism in Africa took two forms: colonies of domination and colonies of settlement. The former were those colonies the colonisers were content to dominate politically, governing them with a limited number of colonial administrators. Colonies of settlement on the other hand were those in which the colonisers, in addition to dominating politically, also settled in in large numbers – they turned them into their homes – on account largely of their congenial temperate weather. Colonies of domination were found mainly in West and Central Africa, i.e. Nigeria, Togo, Ghana, Cameroon, etc. Colonies of settlement were found mainly in Southern and the East coast of Africa, i.e. South Africa, Namibia, Mozambique, parts of Tanzania and Kenya, etc. Colonies of domination gained their independence in the 1960s through peaceful means – mainly conferences convened in the colonial capitals. Settler colonies gained their independence relatively late beginning with Angola and Mozambique in 1975, Zimbabwe in 1980, Namibia in 1989, and lastly South Africa in 1994. Settler colonies were delivered from colonialism via the armed national liberation struggle. Unlike in colonies of domination where the few white colonial administrators packed their bags and left at the moment of independence, politics in post-colonial settler colonies morphs into a new form which is nothing but a continuation of settler colonial relations in economy, knowledge production and law under a liberal democratic framework. The immediate opposite of political independence is the struggle by the black colonized for definitive liberation whose distinguishing characteristic is that after its attainment one does not search for what is black in it. The struggle for definitive liberation is the quest, urge, impulse, prayer, desire, and imperative to surpass forms of self, self-understanding, and the discursive framework for such projects, constituted within the matrices of colonialism. Empirically, it means re-writing the history of African societies from within, foregrounding African modes of cognizing in knowledge production, de-substantialising the enlightenment bequeathed claim at the foundation of modern rational thought that the black colonized must always appear as an object of thought onto which the light of reason is shone by the white subject. In the concrete (settler) colonial situation shifting the ratio between the traditional objects and subjects of knowledge means that the task of thinking ceases to be an exclusive preserve of white (settler) colonialists – those whose sensibilities are drawn from the post-Enlightenment European era – and their acknowledgement that whilst they historically had the right to be ignorant of thought and ideas emanating from the black colonized in the present they have as much a moral as an intellectual responsibility to listen to and be cognisant of their thought-feelings.

In many colonial societies, colonies of domination especially, the struggle for definitive liberation was the occasion for two related processes; the deliberate cultivation and flowering of a cadre of indigenous African intellectuals en masse, and the conscious nurturing of Africa-focused schools of thought – a good example of which is the Ibadan School of Social History in Nigeria– whose intent were to re-write the historical, social, political and economic realities of African people. In Thandika Mkandawire’s (1995) article titled Three Generations of African Academics: A Note we read of the success achieved by many post-colonial African societies in this moment of struggle for definitive liberation. In the thirty-five years of independence from 1960 – 1995 many of these societies had been so successful in producing a mass of indigenous African scholars, such that Mkandawire (1995) is able to disaggregate this cadre into three generations. If the temptation is to contrast this achievement with South Africa’s reality in its twenty-five years of independence, that temptation must be held in check or perhaps the task left for other pens. What the above renders incontrovertible though is a rather disconcerting fact that unlike in other post-colonial African societies wherein political independence served at the same time as the impetus for the struggle/movement to decolonise thought, in South Africa the privilege of white settler colonial thought is that when it enacts itself, it does so conscious that a counter-voice does not exist. The book, Decolonising Jesus, is archetypical. Perhaps we are getting ahead of ourselves. About the book first.

Published in 2019, the book loans its title from the stirrings of the student led agitation for the decolonisation of the university, the academy and the entire knowledge and cultural representation industry in South Africa. In the acknowledgements the author explicitly states that it is a student he had consulted at the University of Cape Town who suggested the title but for a lecture he had been invited to give; ‘She came up with “Decolonising Jesus”, capitalising on the debate amongst South African students about the need to decolonise university education’. Euphemistically known as #FeesMustFall the student movement in many of its intellectual discussions constantly came face to face with the question of the role of religion in the continuing colonial enterprise. The reason is not hard to fathom. Even though it lacked the revolutionary and theoretical vocabulary with which to formulate into a coherent articulation what it instinctually felt and experienced as a deficit in South Africa’s political independence of 1994, the student movement had unknowingly constituted itself into a motive force for the struggle for definitive liberation. That the struggle for definitive liberation in South Africa occurs two decades after independence and that it is violently suppressed by the nationalist liberation movement now in government must surely irk the mind. What it tells us about the character of nationalism in South Africa is a question hopefully other minds will ultimately settle on. Pertinent for us is to recall a point made earlier that in the colonial architecture religion exists and functions as an instrument of epistemic domination, whose dismantling is the object of the struggle for definitive liberation.

It has been necessary to prosecute the point above at length in order that the reader may not wonder why a book on Jesus (religion) is read or examined with such a markedly political lens. As such our reading of the book is directed at ascertaining the extent to which it contributes to the struggle for definitive liberation by decolonising Jesus – read Christian religion. Matthee (2019) also leaves the reader in no doubt about the political directedness of his analysis – the use of Jesus to fan tendentious worldly ideological, often oppressive and unjust socio-political programmes. He locates the book firmly within the discourse of colonial epistemic domination and its dismantling and does so by putting to full use the signifying power and political purchase that the political concept of decolonisation lends. Referring to the colonisation of Jesus Matthee (2019) writes;

“This is at the core of colonising someone, their life, their teaching. The person is used to achieve one’s own purposes, usually for economic benefits and power, and often as trivial as wanting to win an argument, and fundamental to this is to rewrite their history, their life, their teaching…The stand out one over the past two thousand years is Jesus. And this colonisation of Jesus continues in different forms, guises and contexts, unabated; and so wars are purportedly fought and violence justified in His name; and economic theories; and political strategies; and cultural agendas;…and oppressive social structures;…and lavish personal lifestyles; and unhealthy sexual practices…The list is endless.” (p10-11)

Despite the poignancy of the observation Matthee (2019) misses one-point, a fundamental point. We now do know thanks to post-structuralism that every action is preceded by thought and that discourses and their discursive rules render certain actions legitimate and put others outside the range of possibility. Consequently, to re-write a people’s history is never a trivial act, it renders them available for all kinds of self-serving arguments and life diminishing projects, i.e. slavery, and colonialism. Consider for an example the claim in history/Enlightenment philosophy that Africans had no awareness of God prior to slavery/colonialism, or that South Africa was a terra incognita with white settlers and the indigenous people arriving on the land at the same time. For us, the indigenous black colonised, the exercise of re-writing a people’s history has long stamped in our consciousness its deleterious effects. Our being is evidence of the epochal nature of its effects, which continue to be felt long after the fact. Lest to add that its most enduring and decisive impact has not been the loss of land but cognitive domination.

Decolonising Jesus is composed of short provocative essays organised into eleven chapters, with many having been prepared for and delivered at different occasions. The book, it is worth noting, is not an exegetic reading of the bible or scripture. Throughout its pages is an evident attempt to deconstruct the prevalent (colonised he says) image of Jesus, which abstracts him from the everyday world he grew up, lived, and was to conduct his missionary work in. By re-humanising Jesus, contextualising his views and situating his world-outlook in the socio-historical milieu of his society, the author aims to surface a meaning of Jesus’s life, implications of his teachings often glossed over or intently misrepresented by those who colonise him for their enlightened selfish interests. Those who do, create an image of Jesus ‘far removed from the Jesus of the Gospels and the rest of Scripture’ (p10). In Genesis 1 and 2, Matthee (2019) argues is to be found the true uncolonized image of Jesus. It is this authentic figure of Jesus (Genesis 1 and 2) and what it teaches, examplifies or what strictures it prescribes for our worldly existence that the book is sworn to liberating – ‘[M]y invitation to the reader is to join me on this trip, in effect a trip back to Genesis 1 and 2 before the colonisation began…’(p12). Before setting off in earnest on the trip directed supposedly at the decolonisation of Jesus, the author humanises Jesus Christ by sketching the silhouette of his worldly biography – ‘idea of the religious, political, cultural and economic context of the world He was born into, lived in and died in’ (p.14). Drawing copiously from the works of Josephus, Jewish Antiques and The Jewish War, Matthee (2019) in the second essay aptly titled, Context, enters an abbreviated social, political and economic history of Palestine in the period 63 BC – 70 AD. Under a punitive rule of the Roman Empire, Palestine is a colonial society in turmoil, constituted by different social classes/status groups, i.e. Herodians, Pharasees, Sadducees, Zealots, Essenes, etc., whose conflicting interest are mediated primarily by their attitude toward and proximity to Roman colonial rule. And this is the environment Jesus is born in, grows up and lives his working life in. Once located in this context the mythical figure of Jesus disintegrates and in its place emerges an image of Jesus Christ as fully human.

The best articulation of the human as opposed to the mythical figure of Jesus emerges fully in the third and fourth essays of the book. It is best to take Matthee (2019) at his own word as he elaborately paints us the humanly figure of Jesus;

“Jesus was a Jew, born in the heart of the Middle East. There is nothing to suggest that He looked any different to other men in the region. He thus certainly would not have been white, nor indeed black…Given the Jewish custom of boys coming of age at 13 years old, He would have started his work as a carpenter more or less at that age. Thus before he started His public ministry at 30 years old, He would have worked as a carpenter for some 17 years…This must have had an effect on His general physical condition and appearance. His hands also must have been calloused hands” (p30-31).

But Matthee (2019) was not done yet humanising Jesus. The colour of the details he employs in this unfolding project of painting Jesus in a human form are obviously well considered, conspicuous, and attention seeking. In the fourth essay he writes;

“Likewise the life experience of Jesus leading up to His public ministry, is lost on the modern day reader of the Gospels. Deep in His subconscious must have been the struggles, both physical and emotional…What with Mary’s pregnancy outside of wedlock in a deeply conservative society…He was the eldest of 5 brothers and at least two sisters…The precarious financial position of Jesus would have been compounded by the size of his family” (p37-38).

At the end of this effort Jesus does indeed appear not just human but ordinarily human. The ultimate in humanising Jesus we must recall is not only to free him, his exemplary life, normative prescripts and teachings, from capture by those who disfigure them to advance their sectional/ideological interests but to render him and his teaching available, relevant and relatable to our everyday existential questions. How for instance ought those who follow Jesus’s authentic teachings determine or fashion their identities – ‘where as a disciple of Christ, my identity should come from’(chapter 5, p42); learning from Jesus’s example and teachings how believers are called upon to respond in the face of inequality and exploitation (chapter 6); what is the correct and acceptable Christian attitude towards violence (chapter 7); how ought the faithful comport themselves in relation to sex and sexual relations (chapter 8); what prescripts and Christ-like values ought to govern gender relations between man and women (chapter 9); and lastly, what place and role ought Christians accord to money in their lives and societies (chapter 10).

Decolonising Jesus is in a sense a book of two parts. The first part (chapters 1-4) outlines the problematique, colonization of Jesus, the context for its examination and deconstruction. The second part (chapter 5-10) applies the gospel or subscribes the image of a decolonised Jesus to answer, as we noted above, everyday existential questions. Chapter 11 concludes the book. Matthee (2019) stylises answers which emerge from such an application of the Gospel to existential questions that are contemporaneous as the book’s original contribution. For this reason, they deserve a little more focused attention. The radical consequences of the teaching and life of Jesus in relation to how believers ought to constitute their identities is that all forms of collective, sectional identities, including we learn, those of the oppressed and marginalised, be they racial, ethnic gender, class or status groups, must be jettisoned. By his example, Jesus engenders in their place a new sense of identity-fellowship, the community of believers. It is best here again to take Matthee (2019) at his word;

“But because of our human natures we complicate it to water down the radical consequences of His teaching on identity. This applies across the spectrum. Be it the right, the left, black or white nationalism, capitalism, socialism, Marxism, feminism, chauvinism, the rich, the poor – all without fail will try and find justifications or rationalisations to defend the need for their particular personal or group identity. The teaching and life of Jesus simply does not permit such an option for a disciple of His” (p48).

In effect, for believers, both injustice and its victims have no gender, race, class, ethnic, or any other identity marker. It is in the human predilection to turn to violence and to rationalise it as a morally defensible counter to oppression and any other form of human violation that ‘Jesus and his teaching and example desperately and urgently needs to be decolonised’ claims Matthee (p67). Reading, President Mandela’s rationalisation of the African National Congress’s turn to violence/armed struggle in contra-distinction to Martin Luther King’s exhortation against violence, Mathee (2019) denounces the approach, outlook and course of action followed by Mandela and the ANC as out of joint with the teachings of Jesus. Or as having failed to avail itself of the true meaning of the teachings of Jesus, which in this instance is that ‘[W]e are to love our enemies, not kill them’ (p63). What then is the most Christly response to extreme provocation and violent oppression such as the one suffered by the black colonised in South Africa under white people? Matthee (2019) volunteers the answer, it is lengthy, but we must show fidelity to it and reproduce it as is;

“Lest we are seduced to adapt the clear teaching of Jesus on violence by the reasoning and justification for the use of violence by Mr. Mandela, because of the suffering of the oppressed in South Africa at the time and the intractable nature of the government…This brutality notwithstanding, there is not a single reference in any literature of the Christians responding by using violence to defend themselves or to resist…However, in seeking to answer this hard question of how Christians must oppose injustice of all forms, it simply is dishonest to twist the extremely hard and costly teaching and example of Jesus…the way of Christ being to intentionally absorb the blows, whatever those blows might be, so that the violence of the blows does not get passed on to other people…And in this sense the way of Christ is neither fight nor flight, it is a “third way”. Martin Luther King’s militant non-violent civil disobedience would be an example of such a third way…I ask the same question of the struggle in South Africa – what if in 1960 all the Christians in the ANC, the Pan African Congress, and the other movements of the day decided to persist with militant non-violent civil disobedience? Would the oppressors not have been shamed far earlier when they saw folk like the late Chief Albert Luthuli…and thousands of others being shot, beaten and imprisoned?” (p65-68)

It was necessary to read at length Matthee (2019) for the very high moral bar he sets for victims of oppression, the black colonized, because a critical analysis of its full implications reveals what is wrong in/with the book. Colonialism everywhere was always already racial. It is a racial project, predicated on the assumptions of race science and Enlightenment philosophy that the European is superior to the African. At the core of the superior European ‘Self’ is the representation of this figure as the epitome of thought – its beginning and end. Because it is the cause of itself, subject causa sui, this superior European ‘Self’ is capable of rendering its own identity coherent without seeking recognition from the black ‘Other’. But that right is withheld from the ‘Other’ – the black colonised. To simplify: the white European ‘Self’ has the right to be ignorant of the black ‘Other’, his/her thought-systems, religious practices, cosmology, and sensibilities. But the black ‘Other’ not only has to know the European’s (turned white in settler colonies) knowledge system, religion, cosmology and aesthetics, he/she must assume them as the standard. Deviation from this earns him/her – the black colonised – moral denunciation, punitive violence on earth and a promise of hell in the world beyond. Because the black ‘Other’ lacks all the virtues that the European ‘Self’, white settler, possesses in plenitude, i.e. reason, morality, culture, beauty, etc. he/she becomes a symbol of lack. He/she, Fanon says, habits the zone of alterity, the zone of non-being. Such that always responsibility for this figure, this creature of lack, ‘childlike entity’ says Hegel, must rest with the white settler who is a full human. Even for his/her freedom, for its symbolic construction, the black colonised ought to turn to the full white subject – the white settler. Put differently, the task of thinking must remain always an exclusive preserve of the white subject – the white settler. These assumptions and predicates coalesce into what Fanon calls the white colonial unconscious.

The book ‘Decolonising Jesus’ and its author are both representative and expressive of the white colonial unconscious.

If the above sounds abstract, it will help to amplify the argument with evidence from the book. In the denunciation of President Mandela’s (one gets a sense that the author also aims his pen directly to his person) rationalisation of the ANC’s turn to violent armed struggle, one searches in vain for a comment on the moral responsibility of the primary perpetrator of colonial violence – the white settler. In the presentation of the argument not only does the perpetrator walk from the moral debris unscathed, his/her conduct is placed beyond and above moral assessment. If this is not the case, what are we to make of Matthee’s (2019) unashamed mention without comment on the morality or otherwise of the fact that he served in the apartheid Defense Force – ‘[O]nly the year before (1972) I had spent a year in the defense force, sporting a brush cut, being trained to help defend white Christian nationalism against communism’ (p41)? No comment whatsoever thereafter about his – read white settlers’ – own moral responsibility.

Secondly, decolonisation entails undoing the asymmetry created between the white settler and the black colonised. We began the review by pointing out the centrality of religion in the colonial enterprise. Any discussion of decolonisation of religion/Jesus has of necessity to begin with its role in aiding colonialism – its role in the banishing and/or criminalisation of African modes of spirituality. In colonial South Africa among the black colonised there emerged a strong intellectual counter-current to Western Christian religious domination – Black Liberation Theology – influenced of course by developments in Latin America. Alongside this was yet another strong counter-current, more eschatological than intellectual. It institutionalised itself into Independent African Churches. My concern is less about the efficacy of these immanent critiques of Christianity but more about the silencing. It is the representation of the discourse of decolonisation in a manner that precludes from the discursive field engagements with the coloniality of Christ by and among the black colonized. This in a book that claims to have been influenced by the student led movement for the decolonisation on thought in South Africa!!!

The reason we must end here and engage no further with the arguments of the book is because it is itself an example of the continued epistemic domination of the black colonised in South Africa. It should never have been published; its arguments are so banal in formulation and presentation, riddled with misapplication of concepts, shows no regard for acceptable academic strictures of validation, as a whole it amounts to a poor and rather unsophisticated maneuvre to remove the white colonial settler society from the immediacy of colonial relations in South Africa. Even more baffling is the book’s evident determination to shield the white settler community from the implications of its own arguments, for instance on justice, money and gender relations. That it was published notwithstanding, is evidence of the perils of the continued domination of thought, avenues of knowledge production and its circuit of circulation by the colonial white settler community, decades after independence.

Achebe, C. (1957) Things Fall Apart (London: Heinemann)

Majeke, N. (1986) The Role of Missionaries in Conquest (Cumberwood: Unity Movement)

Mkandawire, T. (1995) ‘Three Generations of African Academics: A Note’, Transformation, Vol. 28

Mphahlele, E. (1959) Down Second Avenue (London: Faber and Faber)

Wa Thiong’O, N (1964) Weep Not, Child (London: Heinemann) Decolonising Jesus by Keith Matthee. ISBN: 9781920380496, Pp 101 Paperback

One of the themes running throughout the book is that the Jesus of the Gospels struck a very raw nerve with every power elite of His day, and that is why He was crucified. Central to this was His fundamental challenge to the identity politics of His day. As also made clear in the book, in this regard absolutely nothing has changed 2000 years later.

Reading the review it is clear that once again the Jesus of the Gospels has struck a very raw nerve. A dead give away in this regard is the reviewer resorting to playing the man, and not the ball – wrapped up once again in identity politics, and might I add, conclusions which any reading of the book simply would not support.

So for example his “one searches in vain for a comment on the moral responsibility of the primary perpetrator of colonial violence – the white settler.” Even a cursory reading of the book will show that underpinning my realization as a 18 year old in 1973, was the evil of the system in place and that it was in stark contrast to how the Jesus of the Gospels lived, and what He taught. In fact this is already obvious from the sentences preceding and following the one quoted by the reviewer about my conscription as a 17 year old.

Hence amongst other things at different times my, in the same breath, writing in the book about apartheid, the murderous brutality of the Roman Emperor Nero, Adolf Hitler and the Klu Klux Clan. One struggles to imagine a more condemnatory comparison. In effect, at another point writing that Mandela faced “a ruthlessly oppressive system”, as did Jesus and Martin Luther King. Referring to apartheid I also speculate about what the outcome would have been in the sixties had the ANC and PAC employed a strategy which “shame (d)” the “oppressors”. There are other examples in the book, and the evil of a system such as apartheid in fact expressly or implicitly underpins a fair amount of the book.

What also saddens me is the reviewer’s aside, “one gets a sense that the author also aims his pen directly to his [Mandela’s] person.” There is absolutely nothing whatsoever in the book to substantiate this aside – the question then, why make it? As an aside of my own – contrary to the reviewer’s innuendo, I could not find a publisher in South Africa, which includes amongst the “the colonial white settler community”. I suspect because of the content. It is thus self published. (As regards the aspersions cast on my own conduct by the reviewer, the book is about Jesus, not about me and how I did or did not respond to my insight into the radical demands of Jesus. I partially have dealt with that in other writings.)

Perhaps the problem is that the radical demands of Jesus do not stop at a condemnation of the past or of other people, and therein lies the raw nerve, for ALL OF US. And the need for us daily to ruthlessly ask ourselves how we are yet again colonizing Jesus to serve our own agendas.

The best would be for people to read the book and decide for themselves. It is freely available as a download on my website – keithmatthee.com.

| 1. | ↑ | Colonialism in Africa took two forms: colonies of domination and colonies of settlement. The former were those colonies the colonisers were content to dominate politically, governing them with a limited number of colonial administrators. Colonies of settlement on the other hand were those in which the colonisers, in addition to dominating politically, also settled in in large numbers – they turned them into their homes – on account largely of their congenial temperate weather. Colonies of domination were found mainly in West and Central Africa, i.e. Nigeria, Togo, Ghana, Cameroon, etc. Colonies of settlement were found mainly in Southern and the East coast of Africa, i.e. South Africa, Namibia, Mozambique, parts of Tanzania and Kenya, etc. Colonies of domination gained their independence in the 1960s through peaceful means – mainly conferences convened in the colonial capitals. Settler colonies gained their independence relatively late beginning with Angola and Mozambique in 1975, Zimbabwe in 1980, Namibia in 1989, and lastly South Africa in 1994. Settler colonies were delivered from colonialism via the armed national liberation struggle. Unlike in colonies of domination where the few white colonial administrators packed their bags and left at the moment of independence, politics in post-colonial settler colonies morphs into a new form which is nothing but a continuation of settler colonial relations in economy, knowledge production and law under a liberal democratic framework. |