‘The singer is the defining feature of opera: the living crucible in which music, drama and spectacle coalesce into a single art form’ – Susan Rutherford.

Watching a video of the Jamaican born bass-baritone, Sir Willard White, perform in Mozart’s opera Die Zauberflöte, Musa Ngqungwana fell in love with opera. Back in 1976 when this performance took place, White was one of only a handful of black opera singers in the industry. Twenty years later the video inspired a young South African from Zwide-township near Port Elizabeth to follow his dream, and (roughly) another twenty years on, Ngqungwana himself sang as a soloist at the Metropolitan Opera House in New York. This is no ordinary trajectory, but then, opera is not about the ordinary. As the recently deceased African-American opera legend Jessye Norman said in an interview with the BBC, ‘opera is there to suspend belief’[1]Jessye Norman in conversation with Stephen Sackur on 29 September 2014, British Broadcasting Corporation, HARDtalk., accessed 2 October 2019.. Opera in South Africa has had a history of state sanctioned white privilege, yet many black singers from South Africa’s post-1994 generation have come to embrace the genre, despite its history. ‘Suspending belief’ maybe part and parcel of what happens on stage, but it is hardly a satisfactory answer to the twist of fortunes of the genre and its singers in the South African setting.

Since the 1990s, dozens of singers have formally qualified as opera singers at various tertiary institutions of which the South African College of Music at the University of Cape Town is one of the main players. As a result, local opera companies have flourished, boasting a predominantly black singing corps and keeping the post-1994 privatized opera industry more or less intact. However, the local opera industry today is small, saturated by the ample availability of capable singers, and has proven to be a financially unreliable enterprise. Throughout the past twenty years many black South African singers have found their way onto the stages of prestigious opera houses in Europe and North America, winning competitions and earning international accolades. Musa Ngqungwana is one of them. Like a good many of his peers, he grew up in a township, fell in love with opera, waded his way through church choirs and amateur singing groups, and ended up following vocal studies on tertiary level in Cape Town. More often than not their lives were accompanied by difficult social circumstances and crippling poverty, yet armed with steely determination many have left South Africa to follow careers abroad. Ironically, with a few exceptions such as sopranos Pretty Yende and Pumeza Matshikiza, it seems that most have already been forgotten in their home country.

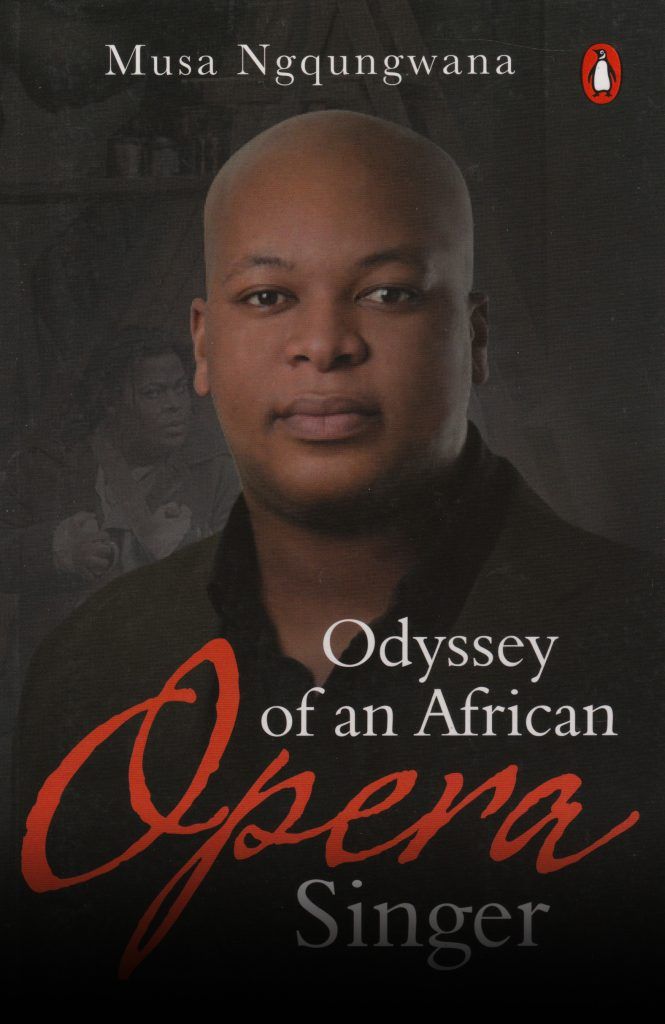

Ngqungwana’s autobiography is an important contribution to the literature on opera in South Africa. On the one hand it attempts to arrest this kind of forgetting and on the other hand it is an account of what it entails for a township youth to set eyes on a career as opera singer. As a bass-baritone in his late thirties, he chronicles his journey from Zwide-township near Port Elizabeth to ‘making it’ as a freelance soloist, singing with opera companies such as the Washington Opera, the Los Angeles Opera, the English National Opera and the New York Glimmerglass Festival. Not only does the book remind South African readers that he indeed has a successful career abroad, it puts the cost of this arduous and exacting journey on record. In actual fact, eighty percent of the book is dedicated to the struggles of his childhood operatic vision and his student years, honing his craft in Cape Town. Only a small section of the book focuses on his international career. It sure is a journey of overcoming setbacks and achieving unlikely successes, and it is understandable that Ngqungwana calls his journey ‘an odyssey’. To his credit, the book is not a rags-to-riches story; being a freelance artist in the highly competitive world of opera is tough on all accounts and the book does not give the impression that Ngqungwana has comfortably arrived.

The book is an accessible and enjoyable read. Ngqungwana has the gift of the gab and draws the reader into the details of his odyssey with gregarious ease. Apart from recounting his less-than-enabling childhood circumstances, he describes his troubles, enthusiasms and follies with a sense of humour and with a degree of acceptance. His priorities are clear throughout the book, not only does he want to ‘sing on stage’ he also wants to know how to socially engage with his environment (he often remarks on the lack of role models in this regard). He yearns for financial security as an opera singer and works very hard for this. He furthermore provides snippets on the internal politics of local churches and the African choral environment, he tells us much about the role that ‘goggos’ [grandmothers] play in the upbringing of township children, and the painful effects of an absent father and mother. The various guardian angels that over the years have helped him along his way reminds one of the fact that everyone needs to be given a chance and that it is the responsibility of all in empowered positions to provide possibilities for those who don’t have them.

However, such stories have been told countless times, not only in biographies but also in numerous literary settings, and often in fiction. How is Ngqungwana’s story different within the broader genre of literature on growing-up in a South African township? Apart from the individuality of him as a person, it comes as no surprise that within the genre of opera today, stories of black African singers are still experienced as out of the ordinary. With regard to the reception of opera, scholarship on the genre and the funding channels that keep the industry afloat, opera remains a rather white affair. My impression is that this book was written for the traditional opera-going audience: white, affluent and elderly, not only in South Africa but also abroad. It may be true that a great number of black singers in South Africa have made opera their own today – incidentally an anomaly on the African continent, if not internationally – but it is equally true that the industry of opera is still populated by the same demography as it was fifty years ago. Within this setting, Ngqungwana’s life is not only unusual, its racial dimension lends it an exotic aura and his otherness provides respite from white bourgeois boredom.

Although the book was not necessarily written with a scholarly readership in mind, there are a number of issues that are glaringly absent from the narrative and that have left this reader unsatisfied. Firstly, Ngqungwana does not tell us much about opera itself. We don’t get to know what it is about the genre (other than singing on stage) that has captivated him to such an extent that he finds it worth his while to continue along this arduous journey. He explains that he also enjoys singing in the jazz idiom, so, why opera and not jazz? Furthermore, within opera there are various sub-genres and it is well known that singers specialize in a certain style depending on the kind of voice they have. Yet, we don’t get to know which operas or roles he prefers and why. There is also no discussion on how he goes about the primary tool of his vocation – namely his voice as an instrument. We don’t know how it sounds, how it is changing (as voices do over time), how he looks after it and what roles suit him best and why they work for him or not. In opera, even for those who do not analyse what they hear and just enjoy the sound and get carried away by the ‘suspension of belief’, the spectacle and bedazzlement of the voice itself is a primary concern.

Then there is the vexing issue of Africa versus the West. In this book these two scenarios seem to embody incompatible worlds, poles apart. Ngqungwana’s township background accounts for a life of economic deprivation and a family constellation that begrudges him his independence and success through their sheer indifference to his international career. It seems that opera has enabled a different life for him, but one that estranged him from his familial roots, a painful price to pay as he observes himself. He gives the reader snippets of his resentment, but there is no further engagement with the discomfort that clearly lives in this dichotomy. And, there are more than just economic polarities: there are cultural and political issues that the reader is introduced to but which remain jarringly adrift in the narrative. The first few chapters of the book provide a vivid description of the effect of his uncle’s political activities during apartheid on his family, including the harrowing experience of his home being burnt down by the police in the middle of the night, his uncle’s incarceration on Robben Island and his visit there when he was a child. Yet, the political awareness that must have resulted from these experiences seems to have no bearing on his life as an opera singer. Similarly there is also no reflection on the musical heritage of his youth and how that speaks to opera as a genre. That is, according to the content of this book. Checking his Facebook profile, Ngqungwana reads African literature that includes authors such as Chinua Achebe, Alan Paton, Ngugi wa Thiongo’o, Ngugi wa Mïriï and Es’kia Mphahlele, and African-American writers such as Yaa Gyasi, J. Drew Lanham and Casey Gerald, all of whom have written cogently about the racial injustices of their world. Ngqungwana may be politically aware, but he has not (yet) found a way to integrate this with his professional life as an opera singer. Opera is a genre where the politics of power holds sway in the same manner as it has done since the nineteenth century, a hierarchy where (white) composers’ and directors’ wishes are slavishly adhered to, not to mention the white, affluent and elderly audience’s appetite for the spectacle of nineteenth century aesthetic values. Opera as a site for social and political activism still seems a long way off.

Although this book is a comfortable and interesting read, my impression is that Ngqungwana’s odyssey is only halfway over. And rightly so, he is only in his thirties and still has decades ahead of him during which much can happen. At present, opera as an art form from the West and Ngqungwana’s African cultural heritage sit uncomfortably next to each other, as if the one exists at the expense of the other. It is my hope that he can find a way to engage with these polarities, to question the aesthetic values reigning in both these worlds, to keep challenging accepted norms and values and invent a dialogue between these worlds, creating perhaps a new synthesis, in itself an odyssey.

| 1. | ↑ | Jessye Norman in conversation with Stephen Sackur on 29 September 2014, British Broadcasting Corporation, HARDtalk., accessed 2 October 2019. |