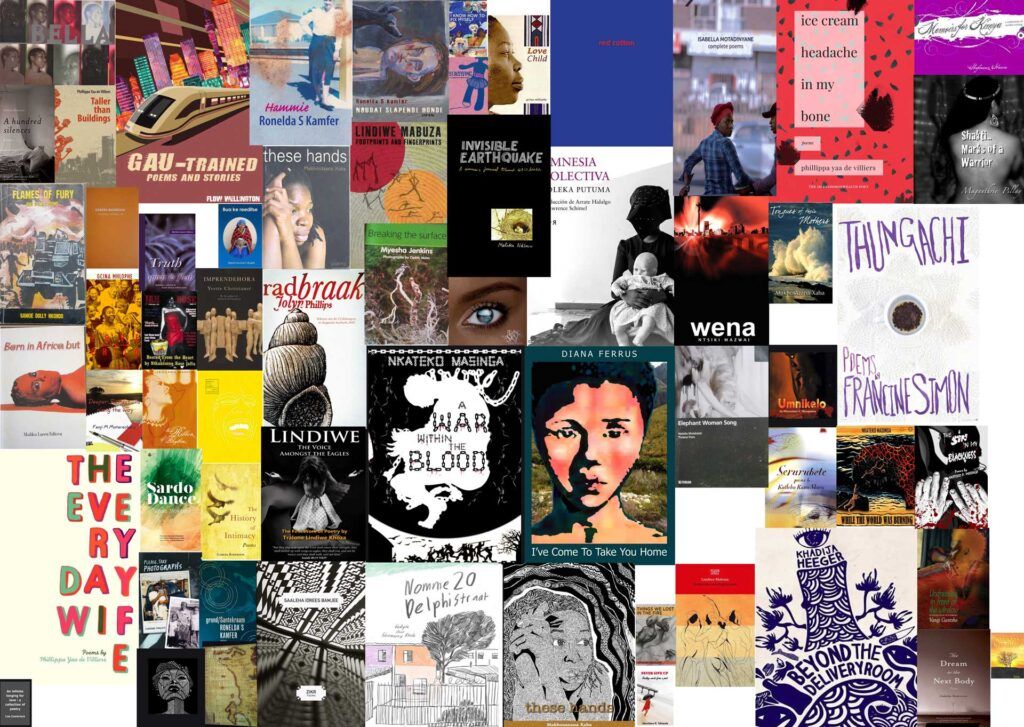

Our Words, Our Worlds: Writing on Black South African Women Poets (2000-2018) edited by Makhosazana Xaba and published by UKZN Press is a celebration of the achievements of a new post-Apartheid cultural phenomenon: the voices of 59 Black South African women poets who published 89 books over the period 2000-2018.

Developments in cultural life, like this poetry phenomenon, are generally the result of political and economic change, and this one was no exception as Gabeba Baderoon observes in her introduction: “(This) book narrates how Black women made a new literary movement in response to being marginalised after the political transformation of 1994 – by both the established, largely white, literary industry and a post-apartheid Black literary culture dominated by men. In an inventive reaction to exclusion, Black women formed collectives that drew on links with theatre, spoken word, music, television and radio to create new forms and themes in writing, and crafted performances that drew unprecedented audiences into poetry.”

And so this is a volume that shouts at maximum volume: we have arrived and we are saying what we want to say with our words. And . . . we are expressing/describing/painting word pictures of OUR world; and doing this for ourselves and for other women. But we are inviting men to open themselves to our work so that you can begin to understand the experiences of women in Mzansi: women who bore the brunt of apartheid; of exclusion; of exploitation; black women at the bottom of the power pyramid; abused and used for sex and production; forced to rock the conqueror’s cradle; forced to fetch the water and the wood.

And so when one thinks of the cumulative impact of these poems, these explorations and articulations of women’s experiences in the past generations of South African living, you begin to realise that a revolution in consciousness is being shaped. All the stereotypes about black women (and the poetry addresses the different experiences of African, Coloured and Indian identities within the frame of gender) are held up and exploded. For male domination is not the only obstacle to living authentically and with full opportunities for self-realization: the sense of powerlessness and dependence that made and continues to make many women accept submission has to be overcome.

Indeed, this phenomenon was born of revolt; it came out of an ‘underground’ as poets like Myesha Jenkins, Lebo Mashile, Tereska Muishond, Makgano Mambolo, Maganthrie Pillay and many others testify. It came out of poetry as a passionate vehicle for change and assertion of particular identities and emotions experienced by Black women – and their right and need to be heard. And so, whereas poetry production, publishing and performance in the 1980’s and early 1990’s was dominated by Black men such as Mzwakhe Mbuli and other protest poets, the late 1990’s saw a new wave of Black women challenge for space and attention as well as a younger generation of male poets writing in a new idiom.

Now this being the case, what frameworks facilitated this mass phenomenon?

In this regard, flowing from the spirit and practice of the 1980’s popular Struggle, it was no accident that it was the formation of poetry collectives (Feelah Sista! in Jozi being one of the key ones – and it’s a pity similar groups in other areas such as Bloemfontein, Cape Town and Durban are not as comprehensively covered in the book) and the nurturing of similarly motivated and operated ‘underground’ poetry sessions which drew substantial participation by young Black poets and enthusiasts.

As a result, Spoken Word poetry beyond the parameters of Apartheid protest flourished and created new dimensions for liberatory expression. There was a sense of the opening of horizons, and with the appropriate organizational frameworks in place, poetry became a perfect cultural vehicle for young people to experiment with the new freedoms of majority rule. In that period it became a point of pride that the new South African constitution guaranteed women unrivalled rights and opportunities; in concrete terms, quotas for women’s representation in government and most civil society formations reached never before seen levels. Taken together, the stage was set for a feminist revolution against both White and Black patriarchal controls and, in literary terms, the old guards with their canon of overwhelmingly male poets were being ‘left in the dust’.

Now all this confirms another central point; this one made by the editor, Makhosazana Xaba, in her introductory essay (Black Women Poets and Their Books as Contributions to the Agenda of Feminism,); namely, that these path-breaking 89 books by Black Women poets were both “literary events and feminist acts”, and hence the agenda of her essay, “to make visible Black women’s creativity as expressed through books of poetry,” takes us into the broader dimension of social impact and, in so doing, into another very important discussion.

For if, by any literary standard (use of language, imagery, style, structure, depth, range of themes, rhythm, flair . . .) much of the really interesting, powerful and downright exciting poetry that has been written and performed in South Africa over the past twenty years has been by Black women, we must also ask if that has translated into meaningful and mass impact on a society gripped by multiple crises and, in particular, the very violent abuse and exploitation of women, of all classes and colours, but in particular, of the Black working class.

In this regard, here are some recent statistics of the extent of this oppression:

1 in 3 women in SA experience sexual abuse

2 in 5 women are beaten by their partners

Half of all working women will be sexually harassed at work

1 in 15 murders of women will be at the hands of their partners

Over the last twelve months, 2,771 women were murdered

40,000 rapes were logged with the police in 2018

41% of people raped were children

(Extract from a statement issued by the Socialist Revolutionary Workers Party, 13 April 2020)

And when it comes to work opportunities and pay scales, Black women are at the bottom of the income pyramid – 45.5% are unemployed compared to 35% of men; pre-school child care is not free and is generally of low educational quality; child maintenance falls mainly on Black women; teenage pregnancy is among the highest in the world as is HIV infection of young Black women between the ages of 16 and 25; school drop outs of girl children in rural areas are at twice the rate of boys with only 52% of all children reaching Matric.

This is a terrifying picture. But does it mean that the body of work created by Black South African women poets is irrelevant and inconsequential? Could they have been expected to reverse this appalling situation or at least make a dent in the numbers of women being abused?

Any materialist analysis of society will confirm that ideas and interpretations embedded in art works (of all genres) can and do influence social norms and behaviour but that unless we change the very basis of our mode of production, we merely tinker with the fundamental power relations; and, in our instance, the gaps in income and opportunity are so great that without a radically new dispensation and the right leadership to get us there, no emancipatory cultural movement can hope to survive. And as much as we might hope to reverse the current crises for women, empirically, the chances of doing so are not promising because we do not have a truly revolutionary political force that can bring this about. And so the movements for radical change have largely disintegrated over the ‘lost’ Zuma years and now in the faltering presidency of Cyril Ramaphosa. In short, the neo-liberal capitalist model embraced by the ANC and its alliance partners has, in addition to confounding other grassroots challenges to their hegemony, limited the chance of a radical poetry movement sustaining a mass base and influencing large numbers of the Black working class with insights and messages for authentic change.

As evidence we might point to the breakup of Feelah Sista! and other collectives since that early period as well as the current decline of Spoken Word platforms. Moreover, this fragmentation, this reversal of collective effort and subsequent individualism and commercialism (where even as sensitive and penetrating a poet like Lebo Mashile bemoans her having had to create and perform sub-standard poetry in order to meet television deadlines) has been speeded up by young poets adopting the government’s neo-liberal assumptions that artists must become entrepreneurs and view their poetry-making as a commercial activity. Without doubt artists need to put ‘bread on the table’, but when this becomes a career that has to be hustled for in the “Free Market’, and vying for media attention (whether social or commercial) and becoming a celebrity (a la soapie stars), and viewing prizes as the raison d’etre of art making, becomes an acceptable mode of living for artists, we undoubtedly find that quality, integrity and content accordingly suffer.

Which brings us to the question of poetry and the academic canon as well as what work is selected for study in schools or bought for state run libraries. Now these are very important spheres of influence for the selection of what is transmitted to new generations and held up as examples of well written, relevant and intellectually provoking art that shapes the future consciousness of a society. And so the preoccupation with what and who is or isn’t in the canon – being an expression of power to determine that consciousness – is a critical area of struggle. In this regard, as part of the decolonization/indigenization movement in South African universities, the new wave of Black South African Women Poets are slowly making inroads as well as in school syllabi. And this, as Khosi Xaba points out in her essay, is testament to their success in marshalling the support of feminist scholars as well as students. In addition, the support that BSAWPs are getting from their sisters and feminist-supporting men has made a massive difference in the field of publishing. The success of women’s presses like Modjaji and Impepho has given women writers new confidence to publish in the knowledge that their books will be bought and appreciated. Overall, BSAWPs have fought hard to achieve this and they have done so through such solidarity.

In this regard, the contributions to the book by Sedica Davids, Tereska Muishond and Ronelda Kamfer stand out for linking their personal struggles to make sense of Coloured identity and their status as women with their discovery of poetry. These are penetrating portraits of how art transforms and creates meaning by delving deep into the divisions of the South African psyche. Pieces by Makgano Mamabalo and Maganthrie Pillay offer similar accounts of personal journeys of creative invention but in different contexts, African and Indian respectively. Having said this, the collection is perhaps too focussed on poets who burst to prominence in the early 2000’s so that younger poets like Sindi Busuku-Mathese, Tumelo Khoza, Koleka Putuma, Nova, Déjà vu Tafari, Mandi Vundla, Jahrose Jafta and many others who ‘came on the scene’ after 2010 are not examined or only mentioned in passing.

In general, the last section which consists of short interviews with various Black South African Women Poetss (conducted mainly by the editor) has some fascinating insights. It adds to the longer pieces on key issues like language use (after all, for most BSAWPs English is not a mother tongue but almost all write and perform mostly in English), the use of radio as a means of transmission, the ways in which a poetry platform is set up and sustained and the impact of being selected for awards (always a touchy subject!).

The piece about Diana Ferrus’ poem on Sarah Baartman inspiring a French senator to support the return to South Africa of the remains of Sarah Baartman was particularly poignant in terms of showing the power of poetry to restore dignity and give voice to past humiliation. It also carries a very useful input from Myesha Jenkins (who has done so much to promote women’s poetry and poetry in general). In answer to the question, “If you could improve anything in the poetry communities, what would it be?” her answer rings out: “It would be more cross-fertilization and sharing of knowledge; more sharing of technical skills; less competitiveness; expansion to reach all provinces; the creation of inter-generational platforms; and somehow seeing ourselves as branches of the same tree, the PO-E-TREE.”

Videos by Aryan Kaganof.