HEIDI GRUNEBAUM

Reflections in a Mirror: From South Africa to Palestine/Israel and Back Again

Preface

The essay below was written in 2014, during Israel’s genocidal assault on Palestinians living in the Gaza strip. Since then, the unrelenting dailiness of the current genocide, ethnic cleansing, forced displacement, enforced mass starvation caused by Israel’s annihilation of life and its conditions in Gaza for the past two years almost overwhelm human comprehension and memory of the long history of the present.

What does it mean to witness each and every day and night, for two interminable years, an unfolding genocide on phones and laptop screens? Countless people witnessing these horrors on their phones screens, far away from Gaza are experiencing a sense of cognitive and emotional overwhelm. Devastated, outraged and in despair, we watch and witness at a distance, as a genocide happens. To bear witness from afar is a moral obligation, a tormenting labour, a Sisyphean task that has to be accomplished. The actions of Israel’s allies, rather than their words of condemnation could make the genocide stop. Yet, as the UN Special Rapporteur on the Palestinian Territories Occupied Since 1967, Francesca Albanese has written in her recent report, “From Economy of Occupation to Economy of Genocide”, those Allies, mainly Western governments and corporations, are directly implicated in Israel’s genocide in Gaza, as well as in the expanding “gazafication” of the West Bank.[1]Francesca Albanese, “From Economy of Occupation to Economy of Genocide”, (A/HRC/59/23) Report of the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in the Palestinian territories occupied since 1967, June 16 2025, un.org On the “gazafication” of the West Bank, see B’tselem’s report, Our Genocide, July 2025, btselem.org

In evermore enmeshed ways, its allies have collaborated and colluded with apartheid Israel’s openly genocidal regime through silence and silencing, indifference and racism, material support and economic gain. The Palestine Nakba, as Rabea Eghbariah argues, has changed over its long duration. Since 1948, it has developed from “from a historical calamity into a brutally sophisticated structure of oppression.” Eghabariah argues for the Nakba to be understood as a legal concept which, as an ongoing structure, “includes episodes of genocide and variants of apartheid but remains rooted in a historically and analytically distinct foundation, structure, and purpose.”[2]Rabea Eghbariah, “Toward Nakba as a Legal Concept,” Columbia Law Review 124, No. 4 (May, 2024): 887-991. The essay that follows engages with the ways that the Nakba and its erasures were approached in Mark Kaplan and my 2013 film, The Village Under the Forest through the lense of being historically implicated in apartheid in South Africa, as well as in in the ongoing Nakba. When I wrote the reflections below, “episodes of genocide” were discerned by a number of Palestinian and international commentators on Israel’s brutal assault on Gaza in 2014. Since 2023, this horrific aspect of Nakba is as incontrovertible. It is borne immediately and directly by each person struggling for life today and to survive in Gaza. The true witnesses.

On the longue durée of the Nakba

When I was invited in 2014 to write about the documentary film, The Village Under The Forest (2013), which I made with Mark Kaplan, I was going to explore what it means to be implicated in state atrocity and historical catastrophe in apartheid South Africa and in Palestine/Israel. I had wanted to write about the psychic landscapes of complicity and how these unfold in our film from a postapartheid Jewish South African perspective. However, in light of Israel’s 2014 genocidal onslaught against Palestinian civilians in Gaza, to write about the politics of the apartheid analogy placing the subject of complicity, the “implicated subject,” at the centre of the discussion seems both obscene and all the more urgent; at once a double bind, a poisoned chalice, and a space of almost impossible thought.[3]Michael Rothberg, “Trauma Theory, Implicated Subjects, and the Question of Israel/Palestine” Profession (2014), mla.org But perhaps it is precisely these difficulties that also lie at the heart of the political effects of measurement, judgment, and the weighing of state and human inflicted experiences of mass suffering. Perhaps such challenges must be navigated when writing about the politics of analogy between historical and human made catastrophes more generally.

The Village Under the Forest set out to explore the question of what it means to be implicated in the Palestine Nakba, in other words, to be implicated in obliterating the traces of life, of people, of history, and of place in historic Palestine. To do this, the film excavates how the pine tree forests planted by the Jewish National Fund (JNF) to “make the wilderness bloom” in Israel were planted on top of the ruins of many Palestinian villages that were depopulated and destroyed during the 1948 Nakba, a catastrophe that continues to unfold as a structure of Israeli settler colonial apartheid. The ruins of one of these villages, Lubya, lie beneath a JNF forest named South Africa Forest. Prompted by a questioning of what it means to have been complicit with apartheid in South Africa, the film explores the historically intertwined processes by which the Palestinian village and the JNF forest have been made and unmade from a non-Israeli Jewish perspective. Using a personal narrative voice, a role that I also play as narrator of the film, the film also grapples with the question of moral responsibility in light of the erasure of the village.

In the film, this question unfurls across the span of three decades that are marked on either side of time’s passage between two different visits to the JNF’s South Africa Forest. In the crossing from South Africa to Palestine/Israel and back again, the film opens a space in which to ask what debts of history might be encountered through that crossing. Between the narrator’s first visit to the JNF forest and her return after learning about the ruins of Lubya beneath an enormous forest of pine trees, the film excavates the unmaking and making of the two counterposed spaces: Lubya and the JNF forest and the conscription of non-Israeli Jews in this process through the “nationalisation” of the Jewish diaspora, a role in which the JNF played a central part.[4]Yoram Bar Gal, Propaganda and Zionist Education: The JNF 1924-1947 (Rochester University Press, 2003).

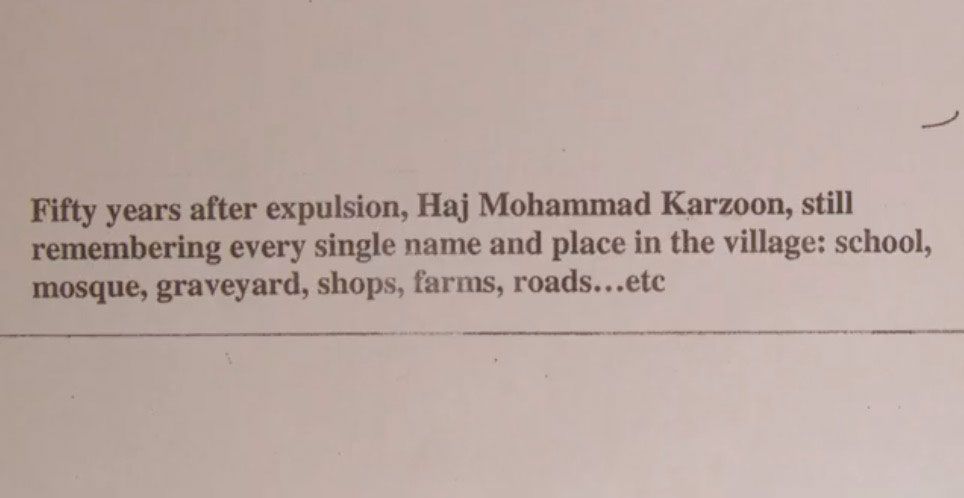

Until 1948, Lubya had been home, life, and livelihood to an estimated 2,730 people.[5]Ibid As with most Palestinian descendants of the Nakba, a robust culture of memory has ensured that the life-worlds associated with the destroyed Palestinian villages from 1948 and 1967 live on in families, books, oral histories, commemorations, intellectual and artistic production, cultural repertoires, photographs, as well as personal and community archives. Mahmoud Issa—social historian, descendant of Lubyans, historical consultant for and interlocutor of the film—has published a social history of the village.[6]Mahmoud Issa, “Resisting Oblivion: Historiography of the Destroyed Palestinian Village of Lubya,” Refuge 21, No. 2 (2003): 14–22. In it he enumerates how Lubya had been one of the largest villages in the Tiberias district with an area of almost 40 square kilometres. Lubya’s “place-ness” was contained in the life of its houses (about a thousand), its lively cultural clubs, mosque, coffee house, travellers’ inn, school, nine shrines, almost forty wells, cemetery, and built structures for grain, livestock, and agriculture. A place bustling with the accumulated stuff of centuries of life in the Galilee: love and politics, debate and scholarship, pilgrimage, travel and hospitality, trade and agriculture, gossip and grievance, and a fierce anticolonial sensibility. Situated close to both Tiberias and Nazereth, Lubya was home and homeland for the few thousand who counted the village as their home in the world whilst encountering the effects of rapid geopolitical and economic change through the early decades of the twentieth century.

Lubya was conquered in mid-July 1948 following three military attacks by units of the Haganah, Israel’s pre-state military formation. It was forcibly depopulated and physically destroyed, along with about five hundred other Palestinian villages, towns, and urban areas, during the so-called War of Independence in Israeli nationalist histories or, for Palestinians, the Nakba. Civilians from Lubya joined the estimated 750,000 Palestinians who were forcibly displaced out of the new state as refugees scattered across the West Bank, Gaza, and countries in the region and other parts of the world, forced into a perpetual and ongoing existential twilight of exile, statelessness, otherness. Some Lubyans, along with Palestinians from a number of other villages, became internally displaced inside the 1949 armistice line. Many had fled from Lubya in the direction of Syria and Lebanon. But many continued to live in the nearby village of Deir Hanna. After the establishment of the Zionist state, an administrative matrix of laws and military orders prohibited displaced Palestinians, “internal” refugees, from returning to their lands or homes. Unlike Jewish Israeli citizens, internally displaced Palestinians were subject to Israeli military rule until 1966. In 1950, the Knesset passed the Absentee Property Law, inventing the term that would come to describe forcibly displaced Palestinians inside Israel, an act of legal naming which irony is as Kafkaesque as it is stunning. The law was also used by the state to appropriate depopulated Palestinian lands and villages, which were then nominally purchased by the JNF through the state’s Custodian of Absentee Property.

In a drive to “Judaize” the land and the landscape of the new state of Israel, official maps were redrawn and Arabic place names were Hebraicised.[7]Meron Benvenisti, Sacred Landscape: The Buried History of the Holy Land since 1948, translated by M. Kaufman-Lacusta (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000). Based on a Talmudic reference to an ancient school of Jewish learning said to have been located in the area, Lubya was renamed Lavie. Two Jewish settlements were established, the first, Kibbutz Lavie, in 1949. An Israeli military museum and memorial dedicated to the Golani military unit that conquered Lubya and other Palestinian villages in the Galilee was also built on Lubya’s lands—and that was one of the places I visited as a young Jewish South African in 1983 at the height of the anti-apartheid struggle and intense state repression—during my participation in a South African equivalent to the American Birthright program called Tochniet Akiva. South Africa Forest was planted over the ruins of Lubya in the mid-1960s. In the years following the depopulation and destruction of the Palestinian villages, the JNF planted some eighty-six pine forests and leisure parks on top of the ruins of destroyed Nakba villages with additional forests planted over villages destroyed in 1967. When I began the research for the film, in 2009, I recalled my first visit to the JNF forest in the 1980s. Palestinians had been erased, rendered “absent” from Israel’s narratives of place, history, belonging, and nationalism that I was taught at school and with which so many non-Israeli Jews were made to identify—we were baldly informed that “Palestinians do not exist.”

At that time, I had not yet the capacity to imagine that trees planted in my name were erasing the presence of the people who had lived there for centuries and been forcibly removed.

In addition, in the 1980s, Israel offered itself, as a way out of the moral dilemmas of whiteness in apartheid South Africa, a promise to which I clung.

Looking in the Mirror

That Israel is an apartheid regime according to its definition in international law is well established. Israeli apartheid bears multiple similarities to apartheid South Africa. When considered together with dates, laws, forced displacements, spatial erasures, settler colonial pedagogies of violence and mastery, and the invention of nationalist histories that justify ethnonationalist claims, the systemic resonances between South African and Israeli apartheid are even uncanny. So too are the psychic landscapes of implicated subjects conscripted into these systems. In such psychic landscapes the distinction between knowing and not knowing can be blurred by the systematic indoctrination of the regime through its education system, structural silence, the political and social indoctrination of ethnic chauvinism and fear, and the cognitive disavowal of complicity. These affective states are taught, learned, conditioned and enlisted by an settler colonial apartheid state which recruits compliance and obedience both as a kind of “active passivity” and through the militarization of collective self-identity and public discourse. Similarities extend to the militarization of social discourse, civic identities, and public spaces, and to the existential fears engendered in the constant production of a dangerous, terrifying “enemy.” They stretch to the familiar rhyming of denial, justification, excuse, moral accommodation, wilful ignorance, “partitioned” thinking/feeling, and the totalizing apocalyptic logic of apartheid state systems reproduced in their political rhetoric and social discourses. And they extend to the ways that complicity and consent are socially marshalled; institutionally policed through censorship, shunning, exclusion, punishment and the branding of those who challenge the systems as “traitors” to “their people.” We wanted to the film to draw these “implicated subjects” to see the film. These were our imagined audience.

Kaplan and I faced two pointed challenges when developing the film treatment and script for the film. The first was how we would interweave the making and the unmaking of the forest/village space within the same visual and narrative framework. The second was how South Africa should figure in the film and what kind of place it would be given in the narrative. We sought a different way of telling such a politically and emotionally freighted story set within the charged space of Palestine/Israel. We wanted to avoid a morally didactic narrative and sought, rather, to raise questions differently from those framed by the false and reductive binary of “two sides” that have characterized representations of “the conflict” in the Euro-American West; different questions that might chart a way toward thinking about moral and political futures in a different way. In this, we wanted the film to raise moral dilemmas for our imagined audience, rather than prescribing solutions. We tried to make a film that could open a space to think. And we sought to avoid dogmatism, didactics, and finger-pointing to enable the complexity of a personal meditation on complicity to resonate more widely with the experiences and emotional responses of other non-Israeli Jews.

To do this, we needed to avoid an individualistic or biographical narrative, which is a danger inherent to first-person narratives generally and particularly in cinematic works in which the visual image of an individual can too seamlessly be viewed as illustrative of a narrative voice. Written as a personal rather than autobiographical narrative, the film’s narrative point of view draws on the experience of so many people who, like me, were not politically active during apartheid. For us, this was a way to raise the question of complicity as a structural and systemic one: to broaden out from complicity as a question of individual agency alone, which autobiography may reinforce rather than destabilize. The personal voice and visual presence of the narrative guide, who appears almost as a shadow, half concealed and half revealed at the edge of the frame attempts to avoid the depoliticising dangers of an individualised autobiography. Rather, the personal voice and indistinct visual presence of the narrator evoke and open a wider set of shared resonances. This, we believed, may enable identification with people who have held similar affiliations to Israel and for whom questioning such visceral and psychically charged loyalties has become necessary, if difficult.

The similarities between apartheid South Africa and apartheid Israel emerge obliquely in the film, cross-referencing one another faintly as traces, echoes, and reflections. These resonances may be discerned in the movement of the crossing from here to there and back again. They emerge where they are not, as a reflection in the mirror. The movement from South Africa to Israel/Palestine and across the time between the two visits to the South Africa Forest both contains and focuses the relation of complicity and response to the unfolding of moral conscience within an embodied and personal life narrative. The narrative voice also shifts and moves in the film from first-person singular to the first person plural and then back to the singular voice. This expansion and contraction of voice suggest that complicity is both individual and collective, structural and embodied, proximate and distanced – and although the frictions and overlapping of the singular and collective voice blur these distinctions, they also require attention.

Opening a Space to Think

For intellectuals, artists, activists and scholars of South Africa and Palestine/Israel, the politics of the analogy of settler-colonial apartheid in both contexts is a complex undertaking on a fraught terrain. On the one hand, analogy may be made without much difficulty, including through recourse to international legal frameworks and moral categories. One only has to examine the more than fifty laws and legal amendments passed by Israel’s Knesset that apportion hierarchically and qualitatively differential civil rights, entitlements, and privileges to Jewish Israelis as distinct from the prohibitions and restrictions on Palestinian citizens of Israel who are relegated to a second class of citizens. The state administers Palestinian life very differently from Jewish Israeli life: one only has to mention Israel’s military administration of Palestinian life in the occupied West Bank and Jerusalem, and the multiply fractured territorial “discontiguity” of the apartheid spatial regime governing all aspects of Palestinian life on the occupied West Bank and Israel’s ongoing siege of Gaza by land, sea, and air.

The “incremental genocide” waged against Palestinians in Gaza since the start of the regime’s blockade of Gaza in 2007 has now become a full scale genocide.[8]Mahmoud Issa, Lubya var en landsby I Palæstina [Lubya: A Palestinian Village in the Middle East] (Copenhagen: Tiderne skifter, 2005). I am deeply grateful to Mahmoud Issa for sharing the unpublished manuscript of the English translation of his book with me.

In contrast, as Hazem Jamjoum argues, analogy can be misplaced when its analytical focus is on the historical specificities of South Africa and Israel rather than the different forms and expressions that apartheid takes in Israel’s administrative matrix of domination and subjection.[9]Hazem Jamjoum, “Not an Analogy: Israel and the Crime of Apartheid,” Electronic Intifada, April 3, 2009, electronicintifada Jamjoum also cautions that the optic of international legal frameworks, conventions, and principles that define apartheid as a state system based on its partitionist and segregationist features rather than as historical example to understand and respond to Israel’s regime of repressive structural, legal, administrative, and spatial expressions that occlude something else, something at the heart of the Israeli regime’s ethnocratic logic: the disavowal of Palestinians as a collective, and as actually existing human beings for which the Palestinian refugee stands as the exemplary figure.

Direct analogy may produce other kinds of foreclosures. In a world in which transgenerational histories and structural reproductions of anti-black racism, black pain and violence against black bodies are at once normalized, ongoing, and systemic, the stakes of analogy are high indeed.

In contemporary South Africa, a reckoning with South African settler-colonial apartheid, the racialised subjectivities it produced and the life-worlds it constrained is but tentatively under way.

Given that the effects of racial capitalism were given an energised afterlife with the adoption of a neoliberal orientation in postapartheid South Africa, this reckoning has different effects and possibilities. Thirty years after the defeat of “legal” apartheid, the question of how we think about apartheid and so-called “postapartheid”, given that this continues to be elaborated with concepts informed by the racial logics it was called on to dismantle, is a question being raised with increasing urgency.

In the fractured and fractious present time, the interstices in which other worlds had been imagined and other subjectivities inhabited during apartheid (and in the struggle against it) are also being revisited. So analogy may risk immuring what is known and knowable about apartheid in South Africa which could contribute to reductionist accounts of apartheid as an historical “event” rather than a structure; or to the present time of the postapartheid as its inevitable and predetermined outcome. This can inadvertently contribute to edifying a white redemption narrative—indeed, I am not certain if the film succeeds in avoiding the latter despite not making a direct analogy. The danger of a morally redemptive narrative of whiteness is sharpened by the absurd proportions—and distortions—that white denialism has taken in contemporary South Africa; a denial that has received a shot in the arm with the rise of the global neofascist right. And a South African discourse in which commitment to dismantle racialized life-worlds and the very idea of race are still incipiently being forged.

With the meditative, poetic register of the narration, we tried to create a filmic space that enables thinking about complicity, about ethical action, rather than foreclosing these by comparing or measuring atrocity or prescribing a solution. This is important if we are to attend to the embodied and psychic life of complicity with historical catastrophe, its ruins, and its erasures from collective consciousness and political intervention. This is important if we are to better think about the consequences and effects of implication in settler colonial apartheid Israel where a militant, militaristic and increasingly messianic ethno-nationalism dominate.

It is important to find a common space for thought, a space for thinking together and out loud. For the fear of existential disintegration against which the cognitive mind shores the self, against which terrified unconscious zones are partitioned, becomes sharpened and more visceral when confronted by moral accusation, no matter its impeccable veracity and truthfulness. And we wanted the film to draw in diaspora and non-Israeli Jews who are questioning Israel’s national narratives and founding myths. We are compelled, as much as we are implicated in these current conditions of annihilation, to act. Of the many ways in which this unfolds, is precisely through narrative and narrative contestation of the dominant logic that normalizes racial subjection, partition, fragmentation, dispossession and Bantustan-isation (as with the recent revival of the “two-state solution”, for example). Such logic presents technologies of militarism and militarised technologies as instruments of “solution”— it is an apocalyptic logic.

Analogy can foreclose these challenges that are political, ethical, and discursive as much as they are conceptual and analytical, for it can work with assumptions of knowing in advance what is being quantified, measured, compared and judged. Today, these are more than theoretical issues. The stakes of analogy are implicated in the moral grounds of thought in times of genocide and war, at a time when the obliteration of human beings unfolds in real time, as do questions of narrative voice and authority, the location of the speaking subject, and the ongoing struggle for the interpretive frame and to narrate.[10]Edward Said, “Permission to Narrate,” Journal of Palestine Studies 13, No. 3 (Spring, 1984): 27-48. They are implicated in the very stakes of bringing into being a future in which the unconditional and indivisible sanctity of all human life, of humanity as such, rather than differentiated modes of state-assigned value, can be imagined and pursued.

The film ends with the suggestion that in enumerating our debt to the obliterations committed in “our name” against Palestinians, the obligation to bring such a future into existence might be navigated by daring to “walk that path: through forest and in between the ruins.” A decade later, through rubble and dust, eyes cast down, in sack cloth and ashes.

Originally published in Jon Soske and Sean Jacobs, eds. Apartheid Israel: The Politics of an Analogy (Chicago: Haymarket, 2015), pp 161-168. Re-published with additional comments in herri with kind permisison of the author. Permission from the publisher requested.

| 1. | ↑ | Francesca Albanese, “From Economy of Occupation to Economy of Genocide”, (A/HRC/59/23) Report of the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in the Palestinian territories occupied since 1967, June 16 2025, un.org On the “gazafication” of the West Bank, see B’tselem’s report, Our Genocide, July 2025, btselem.org |

| 2. | ↑ | Rabea Eghbariah, “Toward Nakba as a Legal Concept,” Columbia Law Review 124, No. 4 (May, 2024): 887-991. |

| 3. | ↑ | Michael Rothberg, “Trauma Theory, Implicated Subjects, and the Question of Israel/Palestine” Profession (2014), mla.org |

| 4. | ↑ | Yoram Bar Gal, Propaganda and Zionist Education: The JNF 1924-1947 (Rochester University Press, 2003). |

| 5. | ↑ | Ibid |

| 6. | ↑ | Mahmoud Issa, “Resisting Oblivion: Historiography of the Destroyed Palestinian Village of Lubya,” Refuge 21, No. 2 (2003): 14–22. |

| 7. | ↑ | Meron Benvenisti, Sacred Landscape: The Buried History of the Holy Land since 1948, translated by M. Kaufman-Lacusta (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000). |

| 8. | ↑ | Mahmoud Issa, Lubya var en landsby I Palæstina [Lubya: A Palestinian Village in the Middle East] (Copenhagen: Tiderne skifter, 2005). I am deeply grateful to Mahmoud Issa for sharing the unpublished manuscript of the English translation of his book with me. |

| 9. | ↑ | Hazem Jamjoum, “Not an Analogy: Israel and the Crime of Apartheid,” Electronic Intifada, April 3, 2009, electronicintifada |

| 10. | ↑ | Edward Said, “Permission to Narrate,” Journal of Palestine Studies 13, No. 3 (Spring, 1984): 27-48. |