ANNEMI CONRADIE-CHETTY

Art refusing to look away

“This is the first genocide in history where its victims are broadcasting their own destruction in real time in the desperate, so far vain hope that the world might do something”. January, 2024. Blinne Ní Ghrálaigh, adviser to South Africa’s legal team during her address at the International Court of Justice.

Reflecting on her visit to Gaza in 2009, Alice Walker writes, “things can be so horrible that people lose the ability to talk about them. They encounter these brutalities, these atrocities, and they literally can’t talk about them, and so we don’t speak.”

The horror of Israel’s actions in Gaza is not only censored on news networks, social media and in academe, it is also silenced because many who are not Palestinian or feel themselves directly affected, are rendered speechless when they do encounter documentation of the genocide. “I don’t have words”, is a sentiment that I’ve heard or uttered myself when seeing footage or reading about new massacres, about the looting, expulsion, kidnapping, torture, vandalism and cruelty perpetrated by the Israel Occupation Force and its enablers. “I can’t look,” is another common response. Both reactions result in further distancing from, and silence about the genocide, and sustain the myth that our lives are not interconnected.

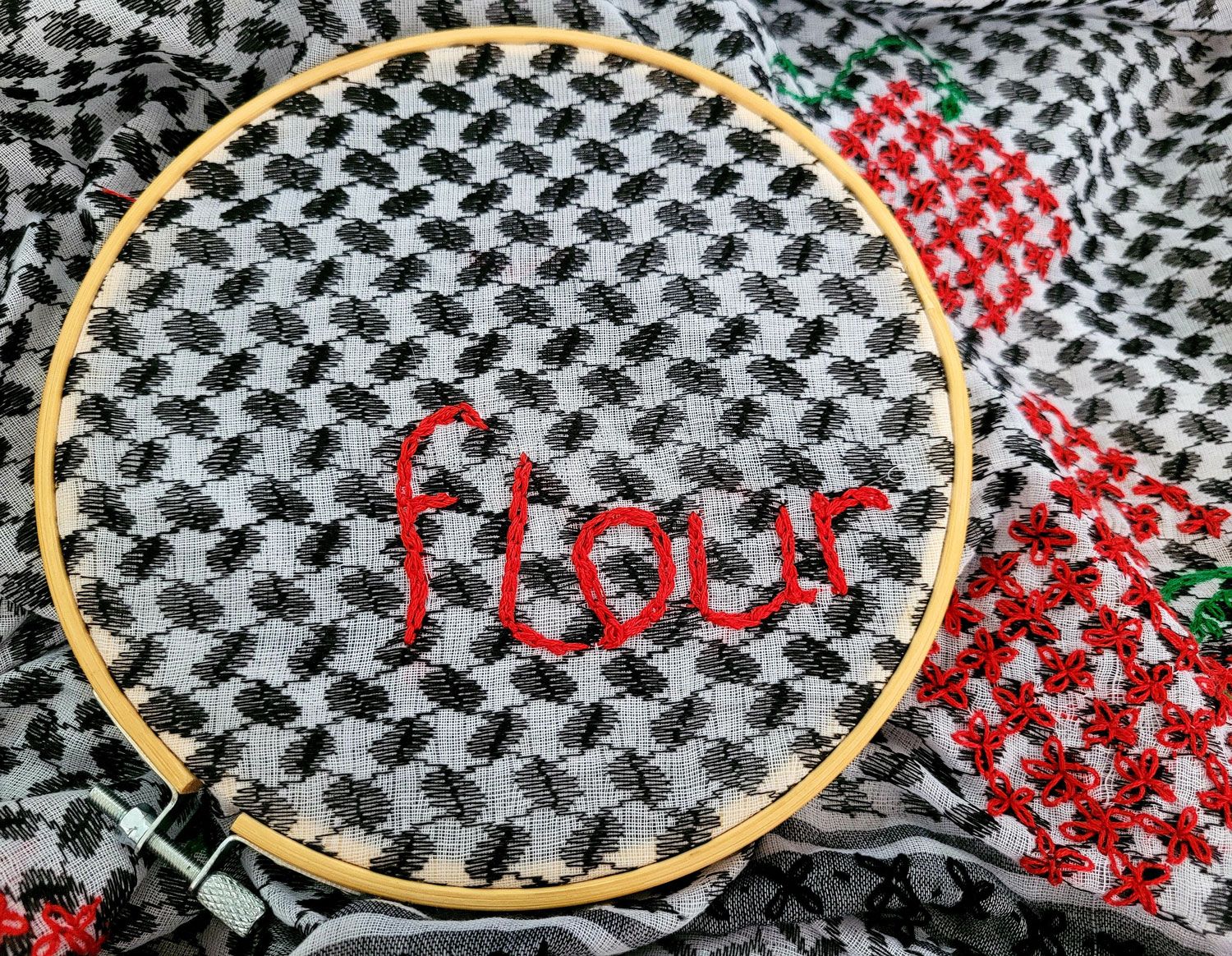

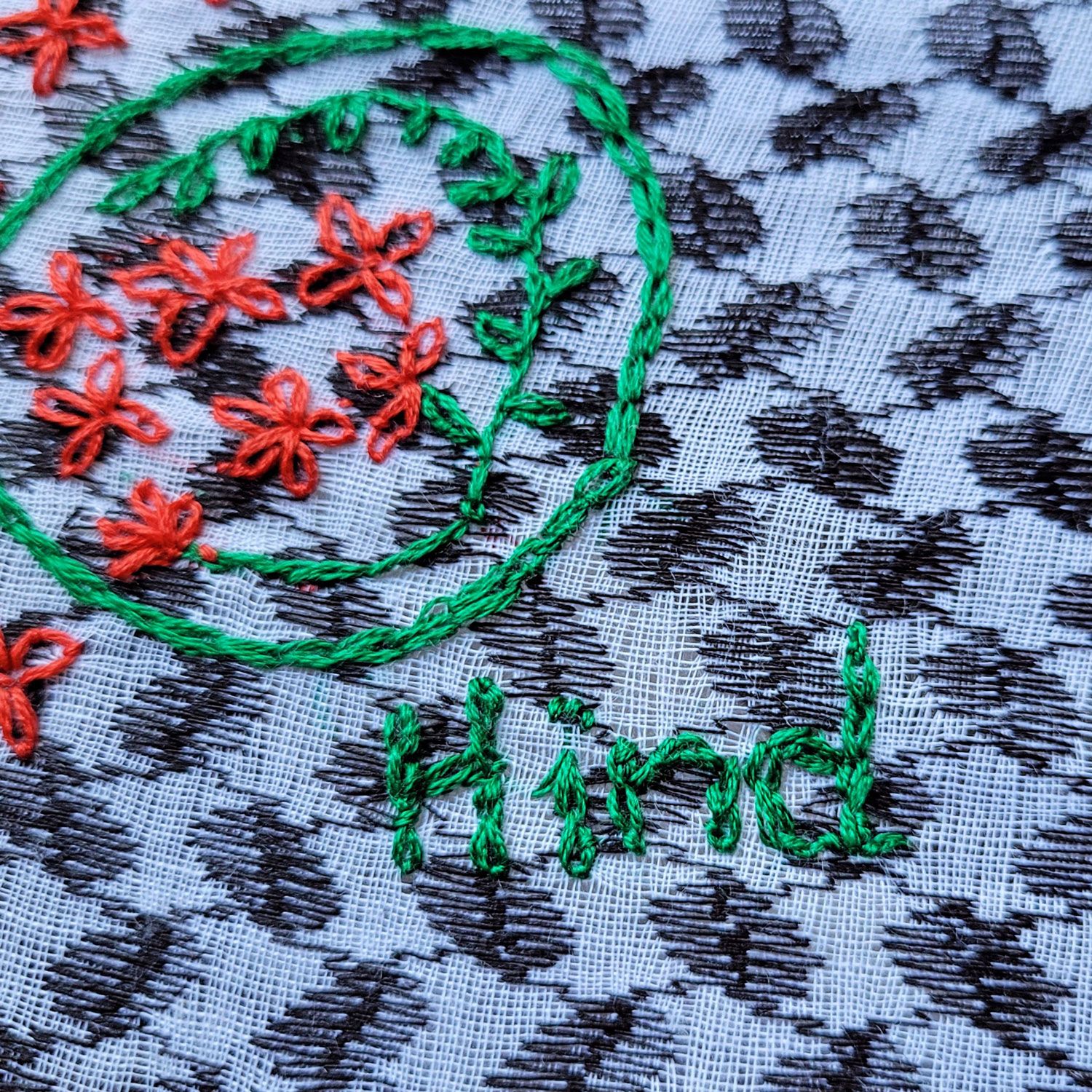

If documentation of the atrocities committed in Gaza and the West Bank renders some readers and viewers ‘speechless’, or they have the privilege to look away and choose not to be distressed, how can artists make people look? This was the question that prompted my embroidered and painted responses to news, images, videos and posts coming out of Gaza, shared by Palestinians who are by no means speechless and have never had the luxury of looking away. I took pictures of my work and shared it, along with links to facts about the represented events and people, on my social media accounts where I knew contacts who might otherwise avoid the news, or hold Zionist views, would be confronted with my work.

The embroidered keffiyeh was updated daily with stitched flowers for health and UN workers, journalists and children killed by Israel. Every flower represents a person. In places, a specific arrangement is dedicated to one person or family: poet Refaat Alareer, Hind Rajab and her family, four babies starved to death in incubators when doctors and nurses were expelled from a hospital and unable to evacuate their patients safely.

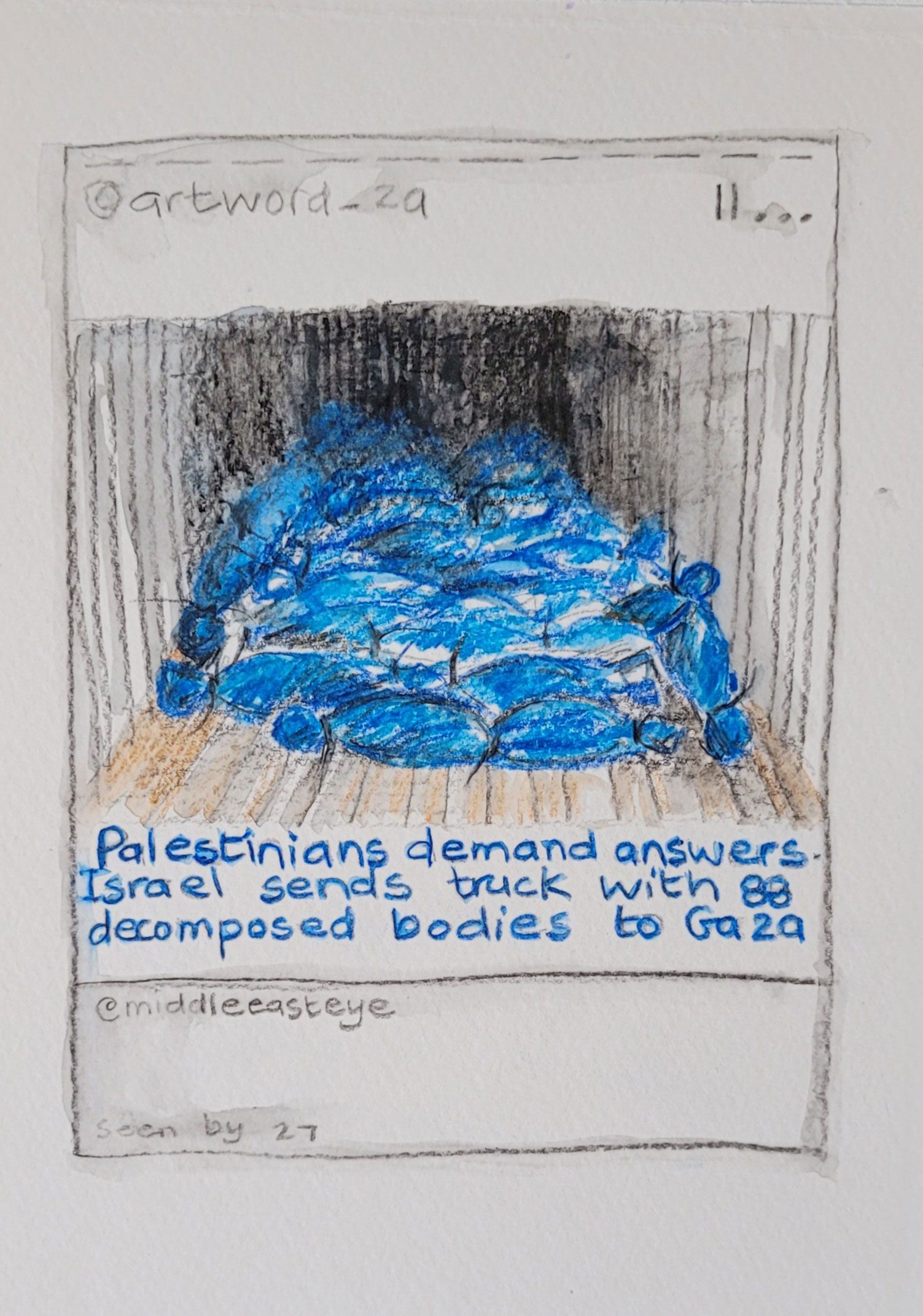

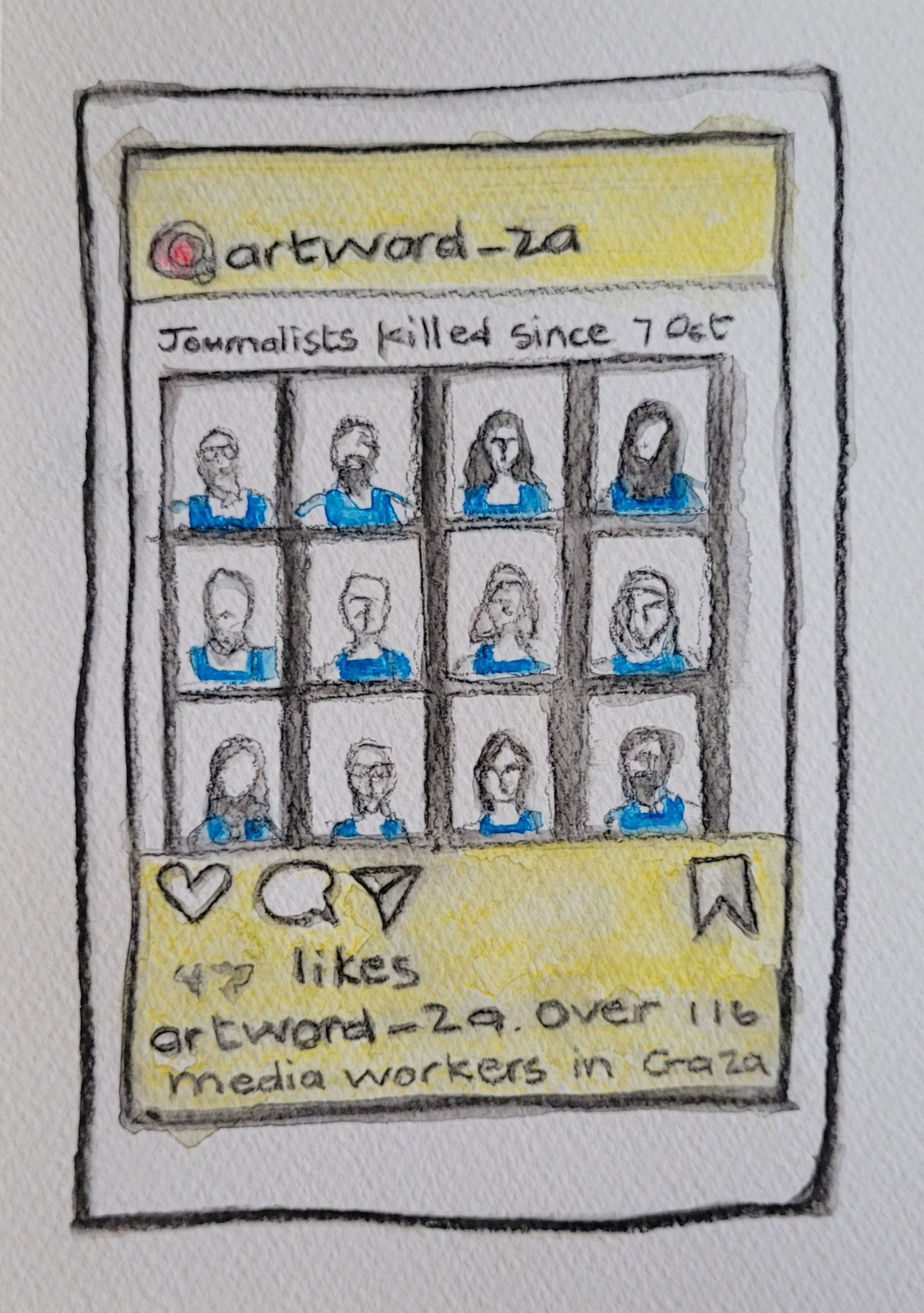

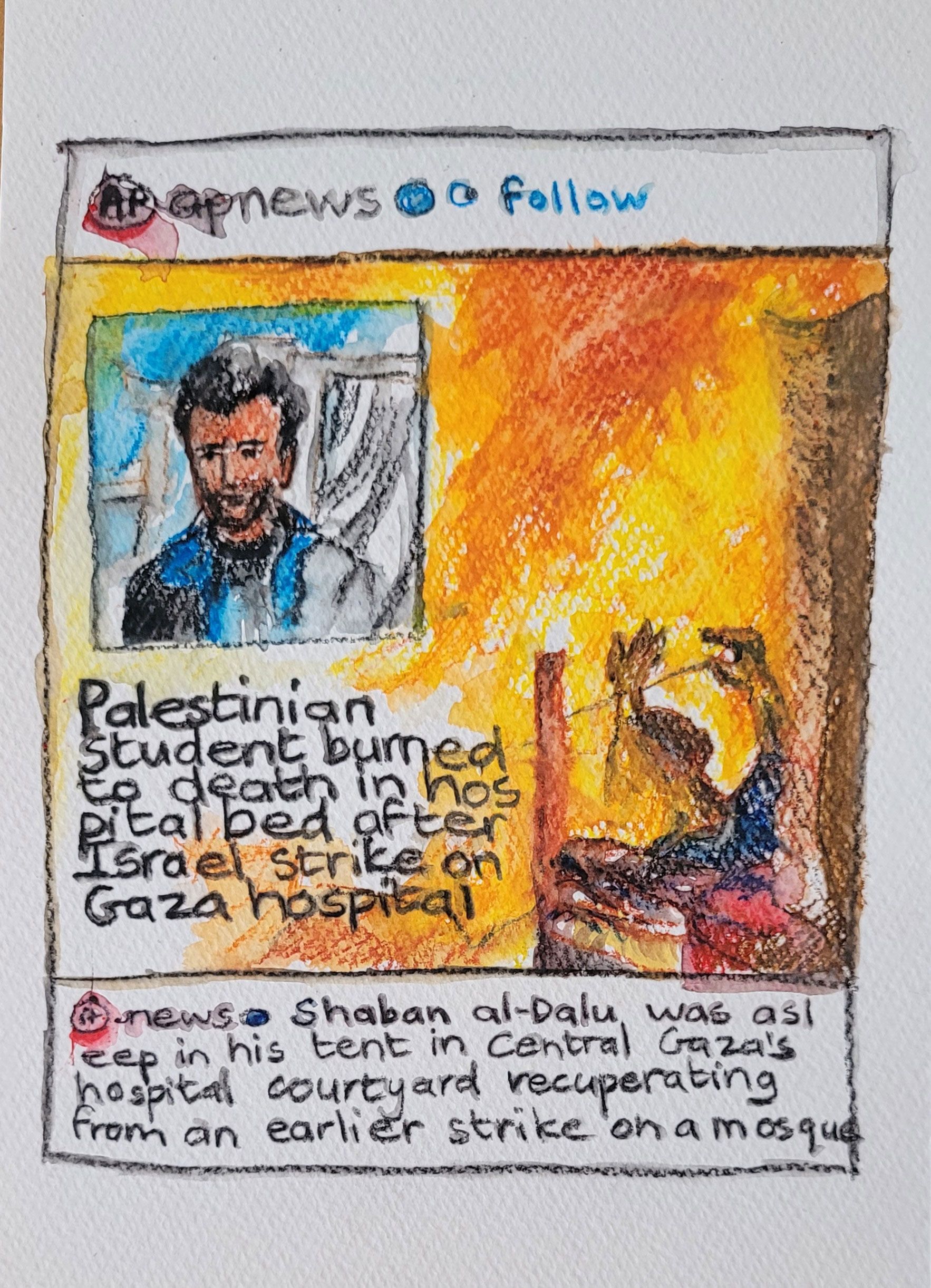

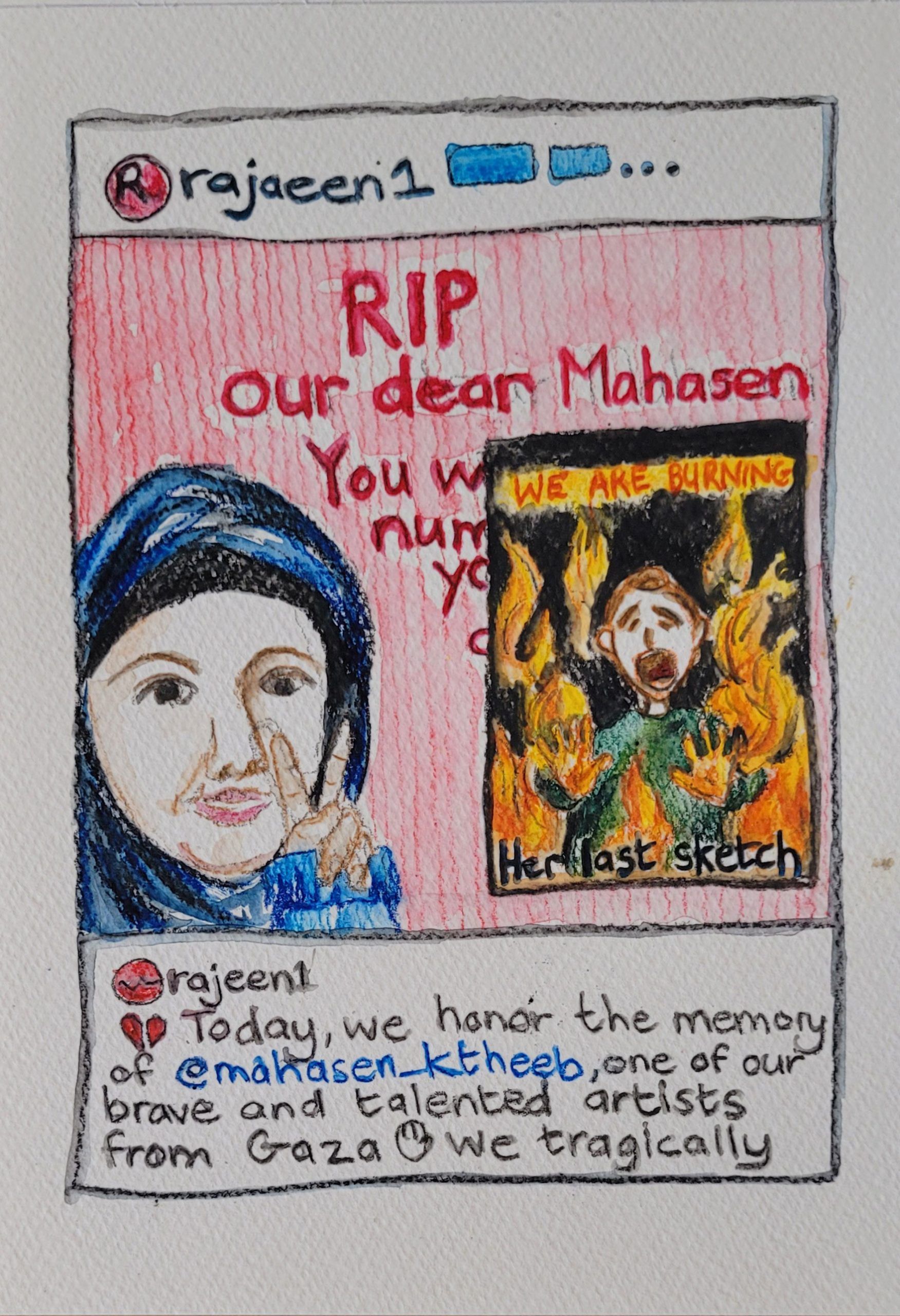

The small ‘Instagram’ paintings cite social media posts about individuals killed by Israeli bombs, news updates on the murder of journalists, or a prayer posted by a reporter, certain of imminent death.

I firmly believe that the refusal of artists to look away will make it harder for others to do so.

Free Palestine.