The following text was written for the legendary series of History Workshops at the African Studies Institute of the University of the Witwatersrand (now Wiser) and presented there in February 1987. The workshops had been founded in 1977 by the likes of Philip Bonner, Peter Delius, Luli Callinocos, Belinda Bozzoli, and Eddie Webster; all scholars who identified with the social history pioneered earlier by British neo-Marxist historians such as Eric Hobsbawn and E.P. Thompson, and who were energized by the growing resistance against apartheid in the wake of the Soweto uprising in 1976. By the mid-1980s, when I was a “Senior Research Officer” at the Institute, the workshops – and the Institute – were led by eminent historian Charles van Onselen. Throughout this period, a heavy emphasis was placed on questions of class formation, working-class politics, urban and rural forms of resistance, along with a strong commitment to bottom-up “oral history.” Expressive culture, by contrast, took second place. If it figured in our discussions at all, it was usually subsumed under what was refered to, without much further elaboration, as a “dialectic of class and race.” While the impact of that focus is evident in my paper, in hindsight I read it as one of only a handful of presentations during that period that sought to strike a balance between a rigid concept of expressive culture as a class-based type of practice and a more flexible view of culture as a sui generis site of dissent and as such being equally worthy of serious analysis. It is reproduced here in its original form (minus spelling errors and other minor issues) together with photos and video material of the performers who entrusted their rich cultural memories to me and future generations.

INTRODUCTION

The crucial role played by the system of cheap migrant labour as the backbone of South African capitalism is reflected in an extensive literature. However, this rich academic output contrasts with a remarkable paucity of studies on migrant workers’ consciousness and forms of cultural expression. Among the reasons for this neglect not the least important is the impact of the South African system of labour migration itself on the minds of scholars. Until at least the 1950s, the prevailing paradigm in African labour studies has been detribalization (Freund 1984:3). Since labour migration – so the argument went – undermined traditional cultural values and created a cultural vacuum in the burgeoning towns and industrial centers of the subcontinent, neither the collapsed cultural formations of the rural hinterland nor the urban void seemed to merit closer attention. The late 1950s somewhat altered the picture, as scholars increasingly focused on what after all appeared to be new cultural formations in the cities: the dance clubs, churches, credit associations and early trade unions (Ranger 1975, Mitchell 1956). This literature emphasized the ways in which the urban population attempted to compensate for the loss of the rural socioeconomic order in “retribalizing”, restructuring the urban forms of social interaction along tribal lines.

Ethnomusicological studies have as yet to come to terms with the profound changes African societies have been undergoing as a result of massive industrialization, labour migration and urbanization. Although, parallel to early studies of African labour, the prevailing paradigm in ethnomusicological studies of African music continues to be detribalization, more recent studies of “town music” in Africa stress the continuity of traditional rural musical expression in a changed environment.[1]Notably Banton 1957, Kauffman 1972, Koetting 1979-80, Little 1965, Rycroft 1977. Traditional music is no longer seen as irreconcilable with urban life, but as a major agent of adaptation to new forms of social organization (Kaemmer 1977). Labour migration as a major factor of urbanization seems to be one of the central mechanisms that directs the transformation of traditional performance practices in the urban socio-economic environment. However, few studies (Koetting 1979-80) have effectively examined the relationship between labour migration and musical performance, and even fewer studies (Coplan 1982, 1985, Collins and Richards 1982) have addressed the complex theoretical problems posed by new emerging forms of urban and popular music in Africa in categories other than “acculturation”, “detribalization”, or their derivatives.[2]See for instance Hampton 1980 and Kauffman 1972.

This paper is an attempt to redress the balance by offering an examination of the social history of a genre of Zulu choral music called isicathamiya. Closely linked with almost a century of industrialization and urbanization in the oldest and most advanced political economy of the continent, this all male vocal tradition is still alive and popular with Zulu migrant workers in the industrial centers of Johannesburg and Durban. Weekly all night competitions that involve as many as 30 choirs, form the vital artery of isicathamiya music. These events are referred to by the English term “competition”, a term most performers prefer to the slightly derogatory term ingoma ebusuku (night song). The Durban based vocal group Ladysmith Black Mambazo introduced this vibrant and long-lived urban musical tradition to international audiences.[3]Until today, the group has recorded over 20 LPs. In 1981 and 1982, Ladysmith Black Mambazo performed in Cologne, West Germany, and in since 1986 they toured the United States on three occasions. See New York Times, May 18, 1986

Although the history of isicathamiya is well documented on commercial recordings and radio transcripts, with the exception of three brief studies (Larlham 1981, Rycroft 1957, Sithole 1979) it has not attracted the attention of ethnomusicologists.

My argument is the following: 1. Isicathamiya affords unique insights into the making of a significant working class culture. Rather than easily adopting a single, unified class identity, migrant workers, amidst the alienation of hostels and compounds, struggled to define an identity around a wide range of focal points like class, ethnicity, and urban status. In South Africa, an understanding of these intersecting class, racial and regional divisions is of vital importance for the analysis of the formation of capitalist society. Previous debates stressed the notion of class as a central analytical category at the expense of other categories, and saw in colour, race and tribe primarily instruments of social control and their acceptance as a form of false consciousness. But in more recent work scholars have begun to realize that the complex realities of expanding capitalism in Africa cannot be grasped solely in terms of its class relations. The numerous divisions of ideology, cultures, political power cannot be subsumed under class conflicts alone. The interest increasingly focuses on the notions of ethnicity and race, not as a substitute for class, but as an important correlate of it. Examining, for instance, the acceptance of racial and tribal forms of consciousness among the urban working-class in Southern Africa, Terence Ranger has correctly identified tribal divisions not only as the creation of the ruling classes, but also as a component of working class consciousness under the material conditions of urban ghettos (Ranger 1982).[4]See also Phimister and van Onselen 1979. Thus, through the expressive medium of isicathamiya performance, migrant workers have been able to express at the same time pan ethnic African nationalist ideology and Zulu nationalism, pride in status as permanent urban citizens as well as rural nostalgia and horror at the evils of the city, and finally, working-class consciousness and resistance to proletarianization.

Although migrant workers have been anxious to dissociate themselves from their own rural background, the lumpenproletariat and the petty bourgeoisie alike, most isicathamiya styles, over the past five decades, have shared many features with the musical idioms of each of these cultural and class contexts. This blending of musical styles in the urban context makes it imperative for the ethnomusicologist and social historian to situate the development and ideology of urban African performance styles within a network of fluctuating group relations. Ethnomusicological studies of South African black performance culture cannot be based on the notion of an organic and homogeneous working-class culture (Bozzoli 1982). Consciousness, defined as “the way in which…experiences are handled in cultural terms: embodied in traditions, value systems, ideas and institutional forms” (Thompson 1968:9), does not derive automatically from an individual’s position in the production process, as much as classes cannot be identified in economic terms alone (Marks, Rathbone 1982). Thus, the history of isicathamiya can largely be seen as a classical example for the necessity to view the formation of working-class culture in relation to the other class cultures that surround it. The relations between musical elements, forms, types and material production are not explained by a single expressive need but by a set of multiple determinations. The way in which these styles and forms are appropriated for use by particular classes operates through what Richard Middleton has called “principles of articulation” (Middleton 1985:28). “These operate by combining existing elements into new patterns or by attaching new connotations to them… Particularly strong articulative relationships are established when what we can call ‘cross-connotation’ takes place: that is, when two or more different elements are made to connote, symbolise or connect with each other.” (Middleton 1985:28)

Interwoven with the history of isicathamiya are some of the major themes and issues in the social history of South Africa. Although isicathamiya is essentially a Zulu idiom, attempts to understand it only in ethnic terms will be as unsatisfactory as an analysis that seeks to look at performance as an expression of a coherent class consciousness. To explore the dialectics of class and race in urban performance is therefore one of the most pressing tasks of urban ethnomusicology in Africa.[5]In African ethnomusicological studies this remains a sadly neglected field, whereas students of popular music, particularly in the United States, have contributed some remarkable work on the topic. See in particular Slobin 1982, Ostendorf n.d. In spite of its ambiguous expressive content that combines an emphasis on rural, traditional values with the self-conscious display of urban status and sophistication, isicathamiya has unjustly become associated with government segregationist policy. However, far from glorifying the “homeland” labour reserves, isicathamiya has to be recognized, as an important medium of expression within working-class resistance to domination and political oppression.

Even under the most repressive labour conditions, social control is never complete.

As Eileen and Stephen Yeo have made us aware, to “assume a uniformity or a totality of control or even a single direction of control (from the top downward) is to neglect the frontiers on which power is contested.” (Yeo and Yeo 1981:132) This presupposes a different view of popular culture and working-class culture from the one which seeks to define popular culture in static terms. Indeed, as R.Johnson has argued, “working-class culture is the form in which labour is reproduced. This process of reproduction, then, is always a contested transformation. Working-class culture is formed in the struggle between capital’s demand for particular forms of labour power and the search for a secure location within this relation of dependency.” (Johnson 1979:237) Isicathamiya performance then is best understood not as the result of social control, nor as pure expression of resistance against proletarianization, but like all forms of popular culture, as the “ground on which the transformations are worked” (Hall 1981:228) between different ideologies and ways of life.

THE HISTORY OF ISICATHAMIYA: STYLE AND CONTEXT

In October 1956, the following article appeared in the Zulu newspaper Ilanga Lase Natal:

The history of the jazbaatjie singers dates back to 1890. It becomes clearer after 1925 and usable after 1939. The legendary Champions were led by Mabhulukwana Mbatha of Baumannville. There are hundreds of them in Durban alone. There are the Crocodiles of Enoch Mzobe, the Home Tigers of Samson Ntombela, the Five Roses of Aaron Ntombela…to name but a few. The jazbaatjie musicians have their own mannerisms. Educationally they are generally literate only in their own language. They dress well and are simple in style. They believe in the principle “as loud as your voice can take it ” when singing. Each member of a group almost tries to sing louder than his comrades. The audience are in most cases men. The few women you see now and then, are admirers of certain individual singers.

The jazbaatjies, as they are commonly known, love to compete among one another and the popular trophy in Natal is a nice live goat for the winners, 5 for the second prize and 2/10 for the third. Their adjudicators are usually picked at random in the street so that they may not know or have any special interest in any individual group. If they are Africans, they stand a good chance of being beaten up should their verdict be queried.

Attempts to bribe adjudicators are often made by some competitors. The competitors pay as much as 2 or more in order to enter a contest and there is a lot of money being made by organizers of such contests. The money comes from the musicians themselves and the spectators are entertained almost free of charge.

The jazbaatjie concerts are an attraction for the semi-literate. The music has grown so popular among Whites that it has been mistaken for pure Zulu traditional music. The “step” of the jazbaatjies remains unequaled in its uniqueness, while their beautiful compositions remained original and simple.[6]Ilanga Lase Natal (hereafter Ilanga), 13 October 1956. I am indebted to Charles Ndlovu for the translation of this quote.

Although the term jazbaatjies has become somewhat obsolete, present day competitions in the single sex hostels near the Durban airport and oil refineries, or on the southern fringes of downtown Johannesburg do not differ substantially from the one the Ilanga correspondent witnessed in the 1950s. Apart from the “mannerisms” in stage behavior and dress, a modern observer would most probably be astonished by the diversity of musical styles represented. Although generally recognized as one of the most advanced forms of Zulu musical expression, isicathamiya reflects a rich mixture of Western, African-American, traditional and modern stylistic sources. American revival hymns, Zulu traditional wedding songs, rock and roll, yodeling a la Jimmie Rodgers – to name but a few, are all part of the choral repertoire. They are the product of intensive experimentation by several generations of migrant workers with the most advanced and popular urban styles available to them. Reflecting upon the experience and struggles of generations of migrant workers, isicathamiya performers molded these diverse idioms into a unique expression of Zulu working class identity.

The evidence available on vintage records, in present-day performance styles as well as in performers’ oral testimony indicates that the first isicathamiya performers drew on a complex mix of both traditional and modern styles that were themselves the products of long processes of urbanization, rural-urban interaction and labour migration; processes much older in any case than the 1890s. What the Ilanga critic did however realize correctly, is the fact that performance styles do not simply spring up out of nowhere. The historian searching for the origins of syncretic African performance styles in South Africa in particular, often finds himself confronted with the musical residues of the early phases of European colonization.

The “pre-history” of isicathamiya starts in the second half of the 19th century when American minstrel shows had become by far the most popular form of stage entertainment in the urban centers. Although a Durban based group, the Ethiopian Serenaders, performed minstrel acts as early as 1858, it was in 1862 that the world famous Christy Minstrels toured South Africa, followed by other illustrious troupes and a plethora of local companies. Despite the crude caricatures of Blacks in minstrel shows, the repertoire, performance style and musical instruments of the minstrel stage were enthusiastically received by the growing black urban population of the late 19th century. As early as 1880, at least one black minstrel troupe, the Kafir Christy Minstrels, was operating in Durban, which the Durban newspaper Natal Mercury paternalistically described as “a troupe of eight genuine natives, bones and all, complete who really get through their songs very well.”

For black audiences, however, no visiting minstrel troupe created a deeper impression than Orpheus McAdoo’s Minstrel, Vaudeville and Concert Company. Between 1890 and 1898, McAdoo, one of the first African-Americans of note to visit South Africa, made two phenomenally successful tours of the country that lasted more than five years, and visited Durban and Natal no less than six times.[7]See also my forthcoming article “A Feeling of Prejudice Orpheus M.McAdoo and the Virginia Jubilee Singers in South Africa, 1890-1898”. Black audiences praised McAdoo as their “music hero”, and at least two choirs, the South African Choir and the Zulu Choir, were formed in imitation of McAdoo’s company.[8]See my forthcoming article “Heartless Swindle – The South African Choir in England and the United States, 1890-1894”. McAdoo’s visits became so deeply ingrained in popular consciousness as a turning point in black musical history in South Africa that the Ilanga critic saw the history of isicathamiya beginning in 1890, and that Thembinkosi Pewa, member of the legendary Evening Birds under Solomon Linda declared: “Our oldest brothers, the first to sing isicathamiya, were the Jubilee Brothers. That was in 1891.” (Interview Pewa)

By the turn of the century, minstrelsy had reached even remote rural areas with a fairly intact traditional performance culture. Mission school graduates formed minstrel troupes modeled on either McAdoo’s company or on the numerous white blackface troupes, and adopted names such as AmaNigel Coons, Pirate Coons, Brave Natalian Coons,[9]Ilanga, May 17, 1912 or Yellow Coons. As late as 1918, scenes like the following, reported from Umzumbe rural mission night school in Natal, were not uncommon:

One of the items was a march across the platform of all the urchins with a bone clapper, at the head of the line…and to the astonishment of all, one of the most heathenish boys stood up and sang Tiperary, keeping time to his singing by the twirling of an invisible mustache.[10]Amy Bridgman Cowles: Annual Report of Umzumbe Station, May 19, 1918, p.7 (American Board Commission of Foreign Missions, South Africa Mission, Zulu Branch 1910-1919, vol.1, Documents. Harvard University.

By at least the 1930s, traditional weddings songs, one of the stylistic sources of isicathamiya became known as boloha or umboloho. Doke and Vilakazi found the term to be etymologically related to Xhosa or Afrikaans for “polka” and defined it as a “dance with boots on (as on farms on festive occasions, Nigger minstrels, etc.)” and as a “rough concert or night carnival party” (Doke, Vilakazi 1948:43). As late as 1934, Percival Kirby was able to document the widespread use of bone clappers called amathambo among rural Zulu (Kirby 1968:10-11), and octogenarian Eva Mbambo, member of the renowned Ohlange Choir, recalls performing on the bones as late as 1928.

Among the most influential troupes that popularized “coon”, ragtime songs and other minstrel material throughout South Africa, was the Ohlange Choir of Ohlange Institute near Durban, founded by African National Congress president John Dube. The choir was led by Reuben T. Caluza, South Africa’s most popular and innovative composer between World War I and the early 1930s. Mission educated performers such as Caluza were responsible for the emergence of precursor styles of isicathamiya, in bridging between elements of American minstrelsy and ragtime songs suited to predominantly urban tastes, and semi-traditional styles. Taking the Ohlange Choir on annual fund raising tours of the Transvaal mining towns and compounds, Caluza brought migrant workers in touch with the most polished forms of dance and topical song of the time. “In the compounds,” choir member Selina Kuzwayo recalls, Caluza’s show attracted “bigger crowds than anywhere else.” (Interview Kuzwayo)

Not only were compound residents impressed by Caluza’s skillful combination of dance, action, and Zulu topical lyrics, but the slick entertainment reflected positive, African images of the ideal urbanite, the “coon”. Not without its own ambivalence, the figure of the sophisticated, self conscious “coon” had not only been a central tool of intracommunal criticism used by early African-American stage entertainers, but it ultimately helped to restore racial confidence (Oliver 1984:108). In the minds of South African migrant workers, the image and its corresponding musical style, soon merged into isikhunzi (coons)[11]E.Sithole maintains that sikhunzi is derived from “grumbling” and that “dancing becomes more important than singing.” (Sithole 1979: 278). The evidence I obtained from iscathamiya performers suggests the opposite., the earliest prototype of isicathamiya.

The 1920s, at the height of Caluza’s popularity and the “ragtime craze” among black South Africans, were a period of explosive industrialization that had profound effects on the lives of millions of black people. More than his skills as a performer and professional entertainer it was perhaps Caluza’s ability to address the precarious living conditions of the growing black working class, that contributed to his popularity among compound residents.

His song Sixotshwa Emsebenzini composed in 1924, depicts the hardship brought about by retrenchment and the job colour bar. Themes such as these are recurrent in later as well as in contemporary isicathamiya songs. Thus in the early 1940s, the African Pride Singers echoed Caluza’s resentment of the job colour bar: Why are they practicing the colour bar? (I.L.A.M. 592S)[12]I am most grateful to Mpumelelo Mbatha for the translations of song texts quoted in this paper.

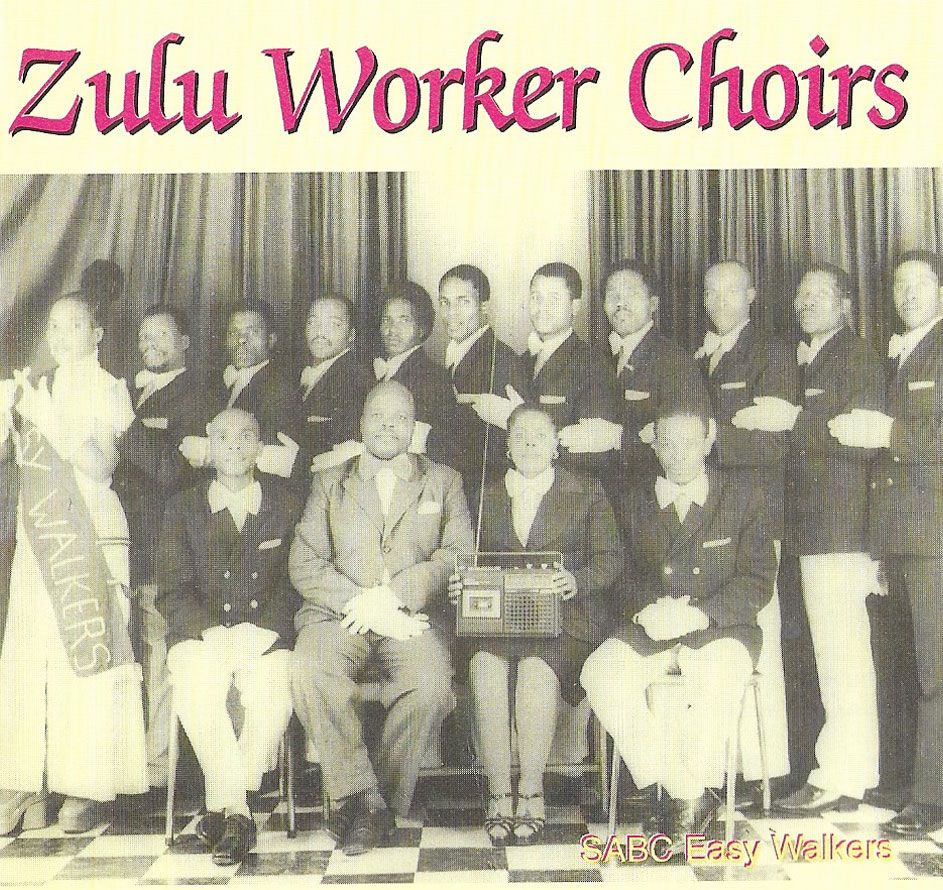

Sawubona baba, a song performed regularly by the Durban group S.A.B.C. Easy Walkers, almost literally repeats Caluza’s song Woza Mfowethu in which the popular composer describes the search for a young migrant worker in Johannesburg by his family:

Greetings to you father.

We have come here on an on an important mission of seeking our brother.

Greetings to you father,

greetings to you mother,

greetings to you brother,

greetings to you sister.

He left his wife and children.

They are suffering back home.

He went in search of work,

but now ten years have passed without us knowing his whereabouts.

We want to take him back to see the children.

Avail yourself, brother!

Don’t hide behind others!

Come, we want to go back with you to see the children.[13]SABC Easy Walkers, February 21, 1982. A version of this song performed by the SABC Easy Walkers is on my record Iscathamiya. Interstate Music. Heritage HT 313, Side Two, track 8.

While the 1920s witnessed the formation of a working class, the 1930s saw it fully integrated into the socio-economic order. It is against the background of working class formation in Durban in the 1930s that the emergence of the first isicathamiya style from the middle class isikhunzi tradition has to be seen. By 1930, the African population in Durban numbered close on 40,000 (la Hausse 1984:243) and by 1935 it was estimated at 56,397. Besides this, over 60,000 migrant workers visited the town every year, most of whom lived in innumerable privately owned barracks scattered over the town, and above all in stinking barracks and hostels near the harbor and the northern fringes of the city. Two groups must be mentioned that performed in Caluza’s tradition and that veteran performers identified as the model for the first genuine isicathamiya choirs. The first was Amanzimtoti, the choir of Adams College in Amanzimtoti near Durban, formed in 1936 by Reuben Caluza after his return from music studies at Hampton Institute and Columbia University. Enoch Mzobe of the Durban based Crocodiles Singers and Ngweto Zondo of the Johannesburg based Crocodiles – both among the oldest isicathamiya groups – agree that “singing really comes from these groups like Amanzimtoti. All these choirs that mushroomed were taking it up from these people, Amanzimtoti in Natal…Amanzimtoti was singing isikhunzi.”

The second group were the Bantu Glee Singers, formed in the early 1930s by Nimrod Makhanya. The Transvaal born Makhanya had been a member of Caluza’s Double Quartet when it traveled to London in 1930 to record for HMV. Back in South Africa, Makhanya devoted his attention to a wide range of popular traditions, including Zulu sketches, folk songs, and ngoma dance songs.

His HMV recordings sold well throughout South Africa and his recording of Jim Takata Kanjani (HMV GU 137)[14]For a reissue of this recording, see my record Mbube Roots. Zulu Choral Music from South Africa, 1930s – 1960s. Cambridge: Rounder Records must have been widely popular among migrant workers, and was quoted by the Crocodiles as one of the oldest isikhunzi tunes in their repertoire.

The Crocodiles were one of the earliest isicathamiya groups in Johannesburg, formed by timber workers from Paulpietersburg in 1938. Although defunct by 1948, several group members were still alive in November 1985 when they agreed to sing Hewu! Kwaqaqamba Amathambo,[15]Ibid. their version of Makhanya’s Jim Takata Kanjani.

Despite the fascination isikhunzi held for migrant workers and compound residents, the performers were regarded by working class audiences “as a better group, as a different breed, a class of their own.” Early isicathamiya protagonists such as Isaac Mandoda Sithole, one time member of the legendary Evening Birds and Natal Champions, was experiencing difficulties in singing isikhunzi, because “they used to change voices. They sang like school choirs.” (Interview Sithole)

Although a product of the middle class concert tradition that regarded dance as “uncivilized”, the ragtime lilt of isikhunzi was ideally suited as dance accompaniment and eventually contributed to the rise of stishi (stitches), one of the first dance styles accompanying early isicathamiya performance by such groups as Enoch Mzobe’s Crocodiles Singers. Evening Birds veteran Thembinkosi Pewa recalls that by the mid-1930s his “elders dressed in three piece suits and shoes with high, revolving heels. They used to wear pants with tapering bottoms.”

Apart from the more urban ragtime and “coon” song influence, veteran performers identify two further, rural sources of early isicathamiya music: ngoma light dance and wedding songs and the hymnody of rural mission congregations in the districts of Dundee, Newcastle and Vryheid in the Natal interior. Apart from being an established coal mining center, this part of the country had long been exposed to intensive European missionization, a fact which accounts for a series of important developments in early isicathamiya music. During the 1920s,[16]For two fascinating studies of ngoma dances, see Clegg 1982, 1984., the area also witnessed a restructuring of rural social relations that resulted in increased demands for African farm labour and massive evictions of peasants from ancestral land. Other areas, such as the overcrowded “tribal reserves” of Msinga were among the first and most important suppliers of migrant labour to the burgeoning industrial centers around Johannesburg and Durban.

Ngoma is a collective term for a great variety of dance styles such as isishameni, umzansi, and umqonqo which originated among farm labourers in the Natal midlands during the 1920s. At about the same time, early protagonists of isishameni created a new song style in incorporating the more Western hymn based wedding songs izingoma zomtshado into traditional material (Clegg 1982:11).[17]Iscathamiya veteran Msimanga stated that “ngoma and wedding songs are closely related and have tremendously influenced iscathamiya.” Interview April 5, 1986. By the 1920s, these wedding songs were already danced to steps derived from the urban “raking” movements popularized by Caluza. Around 1925, near Pomeroy in the remote Msinga area, Gilbert Coka, a thoroughly city bred teacher, attended a female initiation ceremony and was pleased by the simultaneous performance of an “old Zulu dance of hand clapping” and a “Europeanized ragtime march” (Coka 1936:286-87)

To the present day choirs maintain a practice of dancing ukureka (ragtime) while entering the hall from the door. The accompanying songs are called amakhoti (chords)[18]“There is a song that we sing for entering at the door. We call it amakhoti (chords). When you are on stage for competition, you sing imusic for competition. When you sing imusic you don’t move.” (Interview Kheswa). and according to veteran Paulos Msimanga are “borrowed from wedding songs.” As a result of the musical affinity between chords and wedding songs, the corresponding dance movements “have got a similar effect of ukureka,”[19]Compare also I.Sithole’s statement: “Chords are songs that you sing moving, “raking”, making some steps or choreography.” the ragtime steps of wedding songs.

Despite the affinity between rural wedding songs, ngoma dance songs and early isicathamiya styles performers stress the conscious display of Western, “civilized” techniques implied in the use of four part harmony. “In wedding songs there is no control,” Durban Crocodiles veteran Joe Kheswa points out. “A person sings whichever voice part he likes. But in mbube you must be cautious and not produce a dischord.” Four part harmony singing as opposed to unison ngoma songs has a long history among African mission converts in South Africa. In Natal, the site of intensive, especially American missionization since the early 19th century, Western hymnody was favorably received by a people whose traditional musical idioms count among the most developed forms of African vocal polyphony. According to T. Pewa, most isicathamiya performers “first heard of [Western] music at school and were encouraged by teachers to sing church hymns… By singing in church we got to know that there is soprano, alto, tenor and bass, and under Edwin Mkhize, in particular. The latter group had already been in existence since at least 1932, but in 1937 the energetic Linda most likely replaced Mkhize as leader of the Evening Birds.

Throughout the 1930s, the nucleus of working class cultural life in Durban were the compounds and hostels. Two of these, Msizini (Somtseu Road) and Point (South African Railways Barracks), housed thousands of men, and besides a few beer halls and drinking dens in Mkhumbane, on the outskirts of the city, these hostels formed the hub of migrant workers’ cultural activity. The Point barracks regularly attracted spectators of ngoma dances performed by migrants from the Natal midlands, and it was from these surroundings that Linda and his friends drew most of their inspiration. The words of Thembinkosi Pewa, a member of the little known Blue Birds in the mid-1930s and of Linda’s group during the late 1930s, convey the remarkable personality and popularity of the leader Solomon Linda and some of the atmosphere in the early days of isicathamiya singing in Durban:

Singing for the Blue Birds helped me to stay highly “tuned”, helped me not to rust. Blue Birds was just a small “club”. We would sing after drinking. All of us were staying at Mkhumbane, but in different areas. The Evening Birds knew that I was singing for the Blue Birds. As I said we all stayed at Mkhumbane,[20]Zulu name for Cato Manor, one of South Africa’s most notorious slums outside Durban, cleared after mass removals in 1960. but in different areas, so that each member of the Evening Birds sang for a certain club in the area in which he stayed at Mkhumbane. Everybody knew about this. It was only when we were in Durban that we grouped for the big team, the Evening Birds. The Evening Birds were the big team… He [Solomon Linda] was the first. He was older than myself. He was a leader. He was the first soprano. He is the founder member of the Evening Birds. He was from Ladysmith, but he was working here in Durban. His home was at Mhlumayo. He was a nice chap. Nice and clean, too. He always wore white or black and white shoes; black suit, that man. That’s Evening Birds, man. That was their uniform, the only uniform – black suits with white stripes. They are the first group that introduced uniforms in 1938. (Interview Pewa)

By the time Linda left for Johannesburg in 1939, the Evening Birds had firmly established themselves as the most popular group among hostel dwellers and dock workers in Durban’s Msizini and Point barracks. While the remainder of the Evening Birds continued to perform and record under their new name Durban Evening Birds, Linda’s new, Johannesburg based Evening Birds attracted the attention of Gallo producers where Linda was working as a packer.

The first recording, Mbube (Gallo GB 829), issued in 1939, not only became an instant success, but its title soon became synonymous for the entire genre: mbube. Joseph Shabalala, leader of Ladysmith Black Mambazo, suspects:

that it was called mbube because Solomon Linda’s song Mbube was a bit hard [in texture]. I suspect that, but I am not sure of it. The hardening of its texture could therefore have influenced other songs of its kind. Calling it mbube means that the style was sung by many people with strong voices – without a microphone. Mbube means “lion”, because when a lion roars, it is terrifying. Now, this style changed then and was called mbube, from Solomon Linda’s Mbube song. (Interview Shabalala)

Linda’s innovations, however, were not restricted to stage dress and musical structure. I. Sithole recalls that Linda also introduced a soft dance style, called istep (step), that highlighted uniformity of movement and a “soft touch”. Whereas Isikhwela Joe performances were characterized by stiff, immobile body postures, mbube dancing featured slow, but intricate footwork contrasting with a straight, uninvolved torso:

The emphasis was on choreography. They would sing, play a step, make turns simultaneously, all movements simultaneously, and with uniformity. They would not “hit planks”…

“Hitting planks”, forceful stamping of the ground, is the hallmark of ngoma dancing. S. Ntombela recalls that in early isicathamiya dancing, however, dancers “were told to fidget with their feet, but the body had to be straight and uninvolved. And people would turn slowly.” (Interview Ntombela) The contrast between the virile, fighting movements of ngoma and the subtle, almost silent footwork of isicathamiya, signifies the transition from the agricultural pastoral symbolism in ngoma to slick city behavior, and has been aptly described by ethnomusicplogist Elkin Sithole:

The steps in isicathamiya have to be gentle, as if stepping on eggs or tiptoeing on forbidden ground…in cothoza mfana an upright posture is desired. Legs are stretched or kicked out as gently as possible. Even if the halls are uncemented, there is little or no dust at the end of the dance. (Sithole 1979:279)

Performance roles in both Isikhwela Joe and mbube reflect traditional Zulu concepts of musical performance and mission choral practice, but also roles in the workers’ industrial environment. Whereas ngoma dancers are organized in isipani, oxen plough spans, and dance leaders are known as ifolosi, lead oxen (Clegg 1982:13), the lead part in an isicathamiya choir, for instance, is sung by the khontrola (controller), and the response is sung by the “team”. Parts are given English names like “bass”, “tenor”, “alto” and “soprano” or “first part”.

During the mid-1950s, when most choirs preferred the yelling Isikhwela Joe sound, one group had already ventured into new musical terrain. Enoch Mzobe’s Crocodiles Singers, although they remained unrecorded until the late 1960s, had a profound impact on the transition from Linda’s mbube to a smoother, low key close harmony style. Group member Joe Kheswa says that the Crocodiles Singers were among the choirs that “no longer appreciated this style because it’s high and burns one’s voices.” (Interview Kheswa). The Crocodiles Singers were already active in the mid-1930s[21]T.Pewa said about the Crocodiles, that the only jasbaaitjies in existence at the time were the Crocodiles. The Crocodiles were the big ones. They started in the 1930s. We learned about music from the Crocodiles…They were already singing. The Evening Birds came after the Crocodiles. That was in 1937 or thereabout. (Interview Pewa). , but disbanded in 1951, after part of the group had left for Johannesburg. Yet in 1956, the group was reconstituted with new members and had a triumphant come back at the African Art Festival in Durban, where they won the first prize. Songs like Asigoduke[22]See S.A.B.C. Transcription Service LT 10 157, A3 by the Crocodiles Singers and Akasangibhaleli[23]S.A.B.C. Transcription Service LT 10 034, B4 by the Durban Crocodiles, an offshoot of Mzobe’s group formed by former Crocodiles Singers member Absolom Molefe, are clearly indebted to Linda. Although only recorded in the late 1960s, both tunes are fine examples of the transition from mbube to the smooth, low key cothoza mfana or isicathamiya sound of the 1960s and 1970s.

Etymologically, isicathamiya derives from cathama, “to walk softly”, while cothoza mfana is best translated as “walk steadily, boys”. Originally, cothoza mfana was the title of a traditional tune arranged by Gershon Mcanyana, leader of the Scorpions. Mcanyana and his group achieved fame when in early 1966 S.A.B.C. broadcaster Alexius Buthelezi in Durban decided to launch a new show featuring mbube music, using the Scorpions’ tune Cothoza mfana[24]S.A.B.C. Transcription Service LT 6765, A4 as signature tune. The radio show proved tremendously popular and the title of Mcanyana’s tune and of the show eventually replaced mbube as the most common term for Zulu male choral singing.

In terms of musical substance, cothoza mfana shared the same tonal, structural and rhythmic features with its predecessor styles Isikhwela Joe and mbube. Among the most plausible explanations for the emergence of cothoza mfana is the theory that sound engineers who were concerned about the ability of their sound equipment to handle ibombing sounds, encouraged choirs to sing ibombing tunes with reduced volume. (Interview Kheswa) However, it was choirs like the Scorpions and King Star Brothers that must be credited with the introduction and development of a faster tempo of dance and the genuine, structurally innovative isicathamiya style.

Whereas the Scorpions and the King Star Brothers first developed isicathamiya, Joseph Shabalala’s multi gold disc winning group Ladysmith Black Mambazo perfected it. Shabalala’s musical career started in 1958 when he became a member of the Durban Choir in his home town Ladysmith. In 1960, Shabalala came to Durban where the Ocean Blues choir impressed him so much that he decided to join his uncle’s group, the Highlanders. Dissatisfied with ibombing, he formed his own group in 1965: Ladysmith Black Mambazo, the “black axe from Ladysmith”, the choir that defeats all other competitors. The discovery of mbube music by the Zulu service of the S.A.B.C. and Buthelezi’s cothoza mfana show popularized mbube beyond the community of migrant workers. Since the early 1970s and due to the outstanding musicianship of Ladysmith Black Mambazo, mbube music found millions of fans throughout South Africa. Shabalala’s most important contribution to isicathamiya must perhaps be seen in a new narrative style that combines poetic sensitivity with deep, metaphorical Zulu, that gives meaningful expression to the experience and thoughts of millions of black South Africans. “To make a song, says Shabalala, “is like writing a book. Remind the people of the olden things, tell them about the future. Just try to help them.”

MIGRANT WORKERS’ CHORAL COMPETITIONS; CONFLICT AND SOLIDARITY

The idea of competition is rooted in both the social structure and ideologies of pre-capitalist Zulu society and in their transformation through the proletarianization of the rural population. Traditionally, clan antagonism was most visible at wedding ceremonies where both parties performed their respective ancestral songs, ihubo lesizwe, thus giving expression to the rivalry between each other (Coplan 1985:66). With a rapidly disintegrating pre-colonial social order, however, the competitive elements of Zulu society underwent significant modifications. J.Clegg (1982) has shown how, in the 1930s, Zulu ngoma dance competitions arose from the difficulties to contain inter-district tension which had intensified as a result of increased land shortage and diminished employment opportunities on white owned farms in the Natal midlands. Traditionally, such conflicts had been expressed and channeled in some areas into harmless ways in umgangela stick fighting matches (Clegg 1981). Dance competitions, Clegg argues, started to replace this function. (1982:9)

The district based organizational patterns of ngoma dance teams are duplicated in isicathamiya choral competitions, at the same time retaining the idea of channeled conflicts between districts. For most migrant worker choirs, the main basis of association is the network of “home boys”, i.e. of men from the same rural district (inkandla). All 15 members of the Danger Stars, for instance, founded in 1980, come from Amanzimtoti, but only four of the men come from the same family. Likewise, 9 of the 11 members of the Jabula Home Defenders come from Ezingolweni, and only two singers come from the same family. Although friendships formed on the basis of a common work place often overlap with patterns of association based on geographical origin, for most singers like Henry Mdladla the “home boy” link remains the most important entry into isicathamiya performance:

In 1956 I left the mines and found employment in Alberton where I met others who liked the same music. These people came from the same district (inkandla) from which I came. I then formed a choir which I called the NBA Special, because our music came from the farm labourers. (Interview Mdladla)

The structure of present-day competitions to a large extent conforms to standards developed during the 1940s and 1950s, but a picture of these events is perhaps best gained from the report of one of the participants:

The first part of the night was used for competition, then the second part of the night was for dancing just to entertain the crowds. During rehearsals we also spent some time doing isicathamiya dance rehearsals – polishing up our act etc. In actual fact, the competition took about two hours. Thereafter we would dance throughout the night until daybreak. The girls would sometimes, when they see a group that is doing well, stand up, approach that group on stage, take out a scarf and put it around the leader’s neck – a sign of love. Some girls would pin 10 Rand notes on the singers’ jackets. The singer would know that this woman is in love with him. She is his and he is going to take her with him after the competition and the dancing. (Interview Pewa).

One of the main actors in the actual competition is the adjudicator, and T. Pewa’s vivid account of the trouble singers went to in order to find judges in the early days speaks for itself:

This is how we acquired judges. We would all meet at the hall, about 15 or 20 of us – each man representing his group. This delegate had to be a staunch member of that particular group, somebody who was trusted by every member of that group. These delegates would go out into the streets to look for adjudicators. The other group members would be left behind in the hall. On their return they would tell us that the adjudicators had arrived or were coming. The adjudicators were mostly white men. When the judges came, all the groups went outside. The adjudicators would then allocate a number to each group…The adjudicators write numbers on pieces of paper. These pieces would be mixed in a hat; a representative of a particular group would pick one of these pieces…The representatives hated it if they picked the first numbers, like 1,2, or 3. All the representatives and the groups in general preferred to pick the last numbers. You see, the general belief was that if you picked up the first numbers you appeared first and by the time numbers 14 or 15, say, sang, the adjudicators had completely forgotten about what or how the first groups had sung. The singing of the latter groups would still be fresh in the adjudicators’ mind…The judges would be seated in front. Next to the stage. They had to hear and see well. They could not see us when we prepared ourselves behind the curtains. When the curtains were drawn open we would be startled a bit. Then we would ignore them and start doing our thing. After finishing our song we would go and sit with the spectators. (Interview Pewa)

While the performers believe that all human beings share the ability of critical evaluation of music, a white judge offers the added advantage of being unrelated with any of the performers, thus guaranteeing a maximum of impartiality. It is open to interpretation whether in part the use of white judges also reflects middle-class assumptions about alleged white superiority in matters musical. In 1915, the well known Durban choir leader and classically trained musician A. J. Mthethwa already proposed to solve a dispute over competition prizes by only appointing Whites as adjudicators.[25]Ilanga, November 26, 1915 However, as T.Pewa recalls, even white judges did not offer a complete guarantee of being immune to bribery:

You see, Africans were prone to bribery, though some of the whites could also be bribed. This happened like this: say, we at Msizini or Baumannville and we needed some judges. A representative of a certain group would suggest that the whole delegation follow a particular road where he had “planted” a white man beforehand…You see, we preferred families, say if we got a man with his wife and daughter, then we say “win”. There would be no hassles, they would give fair judgments. The best places to look for families we would request as our adjudicators would be cinemas. We would just hang around the cinema exits. (Interview Pewa)

Competitions are divided into two sections. The first part is usually called iprakhtisa, the practice. The second part of the evening is alternatively called imusic, music, or ikhompithi, competition. Iprakhtisa differs from ikhompithi in musical style, dance, dress and audience participation. The participating choirs belong to an association which controls the hall, but some choirs may be invited as guests. However, all competing choirs pay a “joining fee” of up to R20, while the admission for the spectators is around R2. The “joining fee” entitles a choir to enter the competition, but a “request fee” of between R5 and as much as R20 is payable each time a choir wishes to take the stage during the iprakhtisa section. More often than not, the “request fee” is paid by friends, wives, girlfriends or supporters who attend competitions regularly and encourage their favorite choir by joining them on stage during the practice phase.

During iprakhtisa choirs wear ordinary street clothes, but some choirs may also wear long overcoats of the type used at the work place. Some of these coats are reminiscent of the longtailed coats called jaasbaatjies (Afrikaans) or jazbantshis (Zulu), that were popular with Isikhwela Joe performers during the 1940s and 1950s. The flapping tails of jaasbaatjies emphasize the smooth turns of isicathamiya steps which are the highlight of iprakhtisa.

The competition section is tailored entirely to the tastes of the white adjudicators or what performers believe to be the judges’ musical preferences. Except for the entry song performed in the amakhoti, wedding song style, dance is not permitted during competition, “because it was a rule that judges must not be influenced by anything except singing.” (Interview Shabalala) The choirs stand on stage in a straight line and render two or three songs, before leaving the stage, again singing and dancing in the amakhoti style. Choirs are normally given 5 or 10 minutes, a fact which is reflected in the term Five Minutes used by some veteran performers to refer to styles sung during competition. But regardless of whether choirs prefer to call their competition repertoire Five Minutes or imusic, it usually consists of a wide spectrum of styles that reflects both personal idiosyncrasies and varying degrees of urbanization. Some choirs specialize in religious songs ranging from spirituals to revival hymns, while others prefer a mixed repertoire including folk songs arranged for choir, traditional war songs, and rock and roll numbers. Choirs have a repertoire of between 20 and 40 songs on an average, and great care is taken to polish the songs that proved successful in securing prizes.[26]A representative selection of songs most commonly sung during competitons in Durban is available on my record Iscathamiya. Interstate Music, Heritage HT 313.

While regional competition and the “home boy” network reflect the rural origins of isicathamiya performance, more recent developments in Durban and Johannesburg towards the formation of stokfel revolving credit associations have integrated migrant worker choirs more firmly into the cultural networks of the urban working class. From very early in this century stokfel societies had offered working-class women in the emerging locations mutual assistance, in transforming traditional principles of reciprocity into values and goals suited to the urban environment.[27]Space does not allow for a more detailed discussion of the stokfel, but see also Kuper and Kaplan 1944 and DuToit 1969. For a treatment of stokfel and urban musical performance in South Africa, see Coplan 1985:102-105. Although early isicathamiya choirs have been involved in trade union fund raising activities, choirs found it unnecessary to organize themselves along the lines of credit rings that were regarded as being essentially a female affair. However, since the early 1970s, when stokfel associations were still flourishing in the urban ghettos, choral associations emerged that were modeled on stokfels.

One of the biggest associations of its kind is the East Rand Cothoza Music Association which operates in the industrial towns east of Johannesburg. The association was founded in 1978 and counts close on 100 member choirs. It controls performances in the Thokoza hostel near Johannesburg and in a number of other hostel halls. According to its constitution, the aims of the association are as follows:

1. To promote Love, and the development of Mbube Classic among Black Nations.

2. To maintain and enhance this type of National Music as to last for generations.

3. To defend and protect the interest of the Musicians partaking in this type of Music, who are Foreigners.[28]East Rand Cothoza Music Association, Constitution, Second Amendment, p.l.

The association boasts an elaborate bureaucratic machinery of chairman, vice chairman, secretary general, Assistant Secretary, holds executive meetings, Annual General Meetings and issues membership cards to its members. Membership dues are R5 per choir, but, as we have seen, additional fees are payable for participation in competitions.

Associations like the East Rand Cothoza Music Association impose strict discipline on their members. Penalties from R5 up to R400 may be ordered for a variety of offenses, ranging from non appearance at a competition to disobeying the instructions of association officials. In some associations a disciplinary committee keeps a watchful eye over violations, and a “choir that behaves in an unbecoming, or violent manner that might lead to bloodshed, will be banned from all Competitions, until it faces the disciplinary Committee, which shall then decide on the matter.”[29]ibid., p.3 In practice, this ultimate punishment seems to be the exception rather than the rule, and the most frequent offenses seem to be of the order protocolled by the chairman in the minutes of the Durban Glebelands Hostel association:

19.3.1983 There was a quarrel between the Kings Boys and their girls and they eventually beat them. Madevu beat his girlfriend and Ngcobo also did the same to Madevu’s girlfriend.

14.7.1984 New Home Brothers did not report their absence from the hall.

16.6.1984 Harding Boys did not arrive and their absence was not reported.[30]Glebelands Association, Minutes. I am most grateful to Mr Solomon Ndlovu, the chairman, for a copy of the minutes.

The main purpose of choral associations, however, is to provide an organizational basis of fund raising activities. Member choirs take turns in entertaining hostel audiences and in cashing the net profits of weekly competitions. The financial statement of a competition held at the Glebelands hostel in Durban, neatly kept in a book by Solomon Ndlovu, the chairman of the association, may serve as a typical example of these activities. In the competition held on July 28, 1984 on behalf of the Harding Morning Stars, 13 choirs competed. Each choir paid a joining fee of R2, while the gate brought in R62. During iprakhtisa, choirs took the stage 29 times and paid a total of R197.81 request fees. The intake from the kitchen was R152.43, bringing the total net profit up to R438.24. The winners of the evening, Jabula Home Defenders, Warriors Quartet, and Clermont Happy Boys, received prizes of R39, R26, and R19 respectively. Thus, in the early morning hours of July 29, the Harding Morning Stars were able to collect R364.24.

Although association officials and choir members are said to be “involved purely for the love of music and not for money”, some officials, not always without meeting with considerable resistance from choirs, have found a way of securing an extra income:

A choir that is having a stokfel may decide to share it with an official, but they are not compelled to do so – it just depends on the choir… It does, however, happen that sane officials complain when they are not given stokfels, and this at times leads to quarrels, because some officials sometimes go without a stokfel the whole year. (Interview Mdladla)

Although scholars have perceived sharp rifts between hostel dwellers and township residents in South Africa’s black ghettos, stokfel fund raising also extends beyond the association and its members. In H. Mdladla’s view:

people feel that by belonging to an association they are making a contribution to the community in that sometimes choirs are invited to make contributions to community projects such as creches. In that way they feel they are contributing to the upliftment of the community. For instance, our association has two letters from the Thokoza community inviting us to participate in a fund raising campaign to build two more creches in the township of Thokoza. We have in the past received letters frar. SANTA (South African National Tuberculosis Association) requesting us to contribute to a fund raising campaign. (Interview Mdladla)

MIGRANT WORKERS’ CHORAL COMPETITIONS: IDENTITY AND AMBIGUITY

Anyone who has visited one of the men’s hostels in South Africa’s industrial centers where thousands of men are cooped up under an alienated, regimented order that defines the inhabitants in the first instance as labour units and only in the second instance as human beings, will be tempted to view migrant workers’ expressive culture primarily as an assertion of their humanity. Thus, in a study of Tswana miners, H. Alverson has taken as his focus the ways in which migrant workers resist the radical transformation of their personal identity in the mine environment (Alverson 1978). Similarly, C. van Onselen’s study of African mine labour in Southern Rhodesia uncovered the “unarticulated”, “subterranean” forms of workers’ attempts to maintain an identity in the labour coercive mining economy (van Onselen 1980). Self-esteem and the struggle for a personal identity are indeed among the motives isicathamiya performers cite most frequently for joining a choir. Crocodiles veteran Kheswa, for instance, decided to become involved in choral singing “because it makes a person ‘clean’ and proud of himself… Many people love music, because music keeps a person away from hooligans; you become clean, collected and refrain from bad things like drinking liquor, for instance.” (Interview Kheswa) For Paulos Msimanga, the isolation of the hostel in which men are trapped without their wives and families “creates loneliness and nostalgia. This therefore gives rise to singing, which comes as a relief to the tedium of work, nostalgia, and loneliness.” (Interview Msimanga)

A great deal of isicathamiya songs are concerned with loneliness and isolation.

In a song by the New Home Brothers a young worker expresses his grief about the loss of his parents:

One night, when I was asleep, I dreamt of a great calamity.

At that very same moment, I received a message from my relatives.

They were informing me that I was left all by myself,

my parents had passed away.

The mere thought of that day brings me grief.

Tears run down my face when I remember that I am left all by myself.

My father and mother have passed away now.[31]New Home Brothers, March 10, 1984.

In another song, the Durban group Cup and Saucer voice a typical complaint about the lover in the rural home:

She no longer writes to me. What am I going to do, son of Dlamini?[32]Cup and Saucer, March 10, 1984. A recording of the same song, performed by Cup and Saucer on March 10, 1984, can be heard on Side One, track 3 of my record “Iscathamiya”. Interstate Music, Heritage HT 313. Almost identical lyrics are used in HMV JP5 and I.L.A.M. 580S.

Isolation, hurt pride and self respect, however, are the manifestation of feelings shared by individuals whose consciousness embraces a broader set of values and ideologies characteristic of an entire class. A closer look at these ideologies will therefore provide a deeper understanding of the ambiguous consciousness of migrant workers, for many of whom the shift from an agrarian mode of production to permanent proletarianization took place within one generation and frequently even within a fraction of their lifetime. I must disagree with B. Bozzoli that despite the absence of close community connections among hostel dwellers, migrant workers in South Africa can also lay claim to being a class culture (Bozzoli 1983:41). Rather, the diversity of isicathamiya dances and songs reflects a class in the process of formation, whose consciousness frequently embraces contradicting ideas, alliances, and values. It is to these conflicting ideologies in migrant workers’ consciousness that we must now turn in order to complete our understanding of isicathamiya performance.

Even the most cursory glance at the lyrics of both vintage isicathamiya recordings and contemporary songs will disprove claims by apartheid apologists that isicathamiya expresses migrant workers’ uncritical nostalgia for rural idyll[33]This charge has recently been repeated against Ladysmith Black Mambazo. See Coplan 1985:188. and the “traditional” which the sojourns in the cities “will never fundamentally change” (Huskisson 1968:21). Solomon Linda’s Evening Birds, for instance, do not mince words in denouncing rural poverty as the cause of migration.

Not surprisingly, however, their recording of Basibiza made for Gallo in the late 1940s, was never released:

We are dying because of starvation.

(I.L.A.M. 696S)

What is wrong, mother?

We are dying of starvation.

In a more recent song, the Greytown Evening Birds elaborate on the theme of migration and rural poverty:

As you see us present here, we came from far.

We have experienced hardships.

We are roaming because of suffering.

We left our parents and relatives in search of money.[34]Greytown Evening Birds, Feburary 21, 1982.

Driven into the ranks of the urban working class from land no longer able to support a growing rural population, migrant workers resent being associated with a class position whose material and ideological benefits are impalpable. Workers like Solomon Linda’s Evening Birds are in no way different from the majority of migrants who are anxious to dissociate themselves from their rural background:

We do not want young men from our in-laws to call us peasants.

(I.L.A.M. 938S)

We will beat them if they call us peasants.

Pride in the newly achieved urban status, on the other hand, is among the feelings most frequently expressed by participants in isicathamiya competitions. Kings Boys leader Thomas Mtshali, for example, has his own story to tell of “modernization” in his account of the development of isicathamiya from a genre favored by farm labourers to one popular among industrial workers:

Isicathamiya owes its origin to ngoma singing. We started singing ngoma, that was the first step. When we started singing isicathamiya, we tried to be modernized, because when we were in the cities, we were new wearing ties. Now, you cannot perform Zulu dancing, wearing a tie . You have to look for another idiom suitable to the tie. This is where the “step” comes from. The “step” and ngoma are different…The difference is that the step allows you to dance with the tie, a suit, looking really nice, dance and it becomes beautiful. But with ngoma, you cannot perform it with a tie, wearing a suit. Ngoma demands traditional regalia. (Interview Mtshali)

Usually being only temporarily cut off from traditional family structures in the countryside, migrant workers often associate urbanization with the threat posed by declining male authority and changing sex roles within the family. Using the traditional format of izingoma zomtshado wedding songs, the New Home Brothers, for example transpose inter-family satire traditionally expressed in wedding songs, into an attack on urban women’s refusal to bow to parental and conjugal authority:

Sweep the yard, children.

Here comes the bride with bad manners…

The bride has no respect, she puts on trousers.

Oh, the modern practice is bad, gentlemen.[35] New Home Brothers, Durban, March 10, 1984.

Labour militancy among black workers has accompanied the formation of capitalist society in South Africa ever since the discovery of large mineral deposits in the second half of the 19th century. But it was only until much later in this century, that a policy of social control was formulated both by sectors of capital and the local state. At first, the attention focused largely on alcohol as a way of stabilizing a highly fluctuating labour force, but after widespread unrest during the depressed post World War I period more systematic attempts at “moralizing the leisure time of natives” were formulated in Durban and Johannesburg.[36]This whole question has been dealt with at greater length in Couzens 1982. The problem of social control has wider implications for black performing arts in South Africa, if one thinks of social control mainly as the separation of control and ownership from use of means of production and entertainment. From a somewhat different perspective, B. Lortat Jacob has argued that in complex societies, “sectors of production become more concentrated” (1984:29) and that some societies, like Berber society in Morocco create systems of musical production rooted in communities as a protection against professionalism (1981).

In Durban working-class militancy reached a peak in June 1929, when thousands of black workers came out in support of a boycott of the municipally run beer halls called by the Industrial and Commercial Workers’ Union (I. C.U.). Founded in 1919 by Clement Kadalie, the I.C.U. had emerged as the dominant working-class organization of the 1920s and as a potent force in African politics of resistance. After the ensuing riots were put down, the Durban municipality, assisted by a hastily appointed Native Advisory Board, set about to create sports and recreation facilities such as the Bantu Social Centre as part of the strategy for diffusing discontent.

The major Durban companies soon realized the policing effects of “moralizing leisure time” on a discontented work force. Dunlop and Baumann Bread were in the forefront of efforts to control workers’ leisure time. T.Pewa, himself employed at Dunlop after the war, recalls that:

many firms sponsored jaasbaatjies, for instance, Dunlop had their Dunlop jaasbaatjie team. They had a flag, the Dunlop flag. The Dunlop jaasbaatjie team wore a special Dunlop blazer as a uniform – a black blazer with the word Dunlop inscribed on the top outside pocket. Natal Winter Roses had their blazers, too. The one for the Winter Roses was also black with inscriptions. Evening Birds had black blazers with distinctive white stripes as uniform. The Dunlop officials liked ngoma dance and the jaasbaatjies. There was a compound at Dunlop. They also liked soccer. The same applied to the Durban Municipality – they had ngoma, jaasbaatjie and football. The Federated Wholesale Meats at the Maydon Wharf had the Blood and Snow, that is the football team. There were also ngoma dancers and jaasbaatjies.

Question: What was the name of the group from Dunlop?

Answer: It was just Dunlop. There were several clubs as it is today, for instance, there was the B.B.Tigers from Baumann Bread. There was also the B.B.Tigers from the same firm – this is the singers now, the jaasbaatjies. You see, you couldn’t be employed at Baumann Bread if you could not dance ngoma, just like Dunlop. There were things you were asked as a prospective employee. “Can you play football?” If no, then, “Can you sing jaasbaatjie music?” If no, then, “Can you do ngoma dancing?” If you answered to the negative to the three questions you were out. No work for you. Many firms did this at the time in Durban. These questions were asked at the gate of each firm.

A more recent example of companies’ continuing concern about increased productivity and support for “moralized” leisure activity is the foundation of the Kings Boys, whose members first “belonged to a football team called Wendol Vultures, working at Wentworth hospital.” The arrival of a new superintendent, however, meant the premature death of the Wendol Vultures, because he

discouraged us from playing football because we would have a lot of injuries, and find that on Mondays we did not go to work, because of the injuries sustained in the soccer matches. Then he stopped us from playing football. Thereafter we had a time of stagnation, then we decided that rather than loitering around we would form a singing group which won’t injure us. (Interview Mtshali)

Despite a strong legacy of coercion in South African labour and class relations, the type of social control exercised in South African compounds and hostels was never developed enough to allow for a total submission of the work force. Dunbar Moodie has shown that the regimented world of the gold mines and compounds and hostels leads to a fundamental transformation of workers’ identity. But this harsh and alienated environment does not simply reformulate the miners’ identity by total social control. In order to maintain some autonomy, workers participate in the system by “working the system”. (Moodie 1983) Similarly, isicathamiya performers found in management’s incursions into their leisure time an ideal means to “work the system”. Musical talent or sporting inclinations, says T. Pewa, not only increased the chances of being employed, but also the prospects of obtaining less strenuous work:

As a result of this, some guys, that is work seekers, would carry tennis balls with them and start playing in front of the gates at the firms, just to display their skills, showing styles, so the prospective employers be impressed. Even people who were already in employ would tell their employers: “Look, there is somebody who sings well and we would like you to employ him” or a good ngoma dancer or whatever the case may be. The employers would say “Yes, we want good singers here, good ngoma dancers, etc.” …

Question: Why was this?

Answer: They wanted the best.

Question: What is the connection between the best singer and the best worker?

Answer: You see, this was unskilled labour – mixing some chemicals at Dunlop or skinning cattle at the abattoir – unskilled labour. You do not have to be taught how to do unskilled labour. You do not have to be trained. This type of work was reserved for football players. Not a heavy job. Even the singers, they were not required to do sweated labour. Take Dunlop. If you were either a singer, ngoma dancer or football player you would not be expected to work in the mixing plant as this was the worst department. There was a lot of dust and people who worked in this department were prone to diseases, especially chest diseases.

Question: Were you given time to practice?

Answer: We knew the time for doing that. What they were concerned with was the performers’ well being. They had to be kept in trim condition, just like race horses. (Interview Pewa).

Attempts to resist the submission under the capitalist order have a long history among migrant workers and were not confined to the everyday tactics of “working the system”. Strike action and protest meetings among Durban’s dock workers, for instance, have long been an essential component of migrant workers’ resistance (Hemson 1979), and until at least 1930, as we have seen, have been linked with organizations like the I.C.U. The year 1930, however, marked not only a new departure in capital’s tactics of controlling the labour force, but also in union politics towards acquiescence and negotiation. Thus, the success of municipal policies of social control can also be measured in the shift that took place in I.C.U. activities from political agitation to providing entertainment for workers. Ever since A.W.G.Champion and the Natal branch seceded from the parent body to form the I.C.U. Yase Natal, numerous isicathamiya choirs had maintained loose links with the I.C.U. But it was only after the 1929 riots that entertainments at the I.C.U. owned Workers’ Club in Durban featured regular isicathamiya performances interspersed with more “respectable” dance and concert events.

The year 1932 seems to have been a particularly active one, because “Stage Manager” H. Msomi was able to present such diverse groups as the Sunbeams, Dem Darkies from Pretoria, the Blue Dam Bees from Durban, and the Mad Boys from Johannesburg on three consecutive nights in April.[37]Isaziso, University of Cape Town, Forman Papers, 47L, BC581 B22.7. I am indebted to Paul la Hausse for bringing this and other bills to my attention.

The I.C.U. Hall, he claimed, attracted choirs from all over the country, “because peace prevails in this place.”[38]ibid. In June the same year, under the motto “The more we are together, the happier we will be”, mission school tap dance troupes such as the Midnight Follies and the Famous Broadway Entertainers appeared as well as isicathamiya groups like the Moonlight Six of I.C.U., the Zulu Male Voice Party, and the Tulasizwe Choir.[39]Isaziso, University of Cape Town, Forman Papers, 47L, BC 581 B22. The year was rounded off with a “unique entertainment” by the Dixies Raglads from the Amanzimtoti mission school and the Apologise Voices from Izingolweni College.[40]Isaziso, University of Cape Town, Forman Papers, 33L, BC 581 B22.ll.

Notwithstanding the focus on “peace” and “happiness” I.C.U. ideologies continued to express populist opposition to white rule throughout much of the 1930s. As late as 1938, Solomon Linda’s Evening Birds appeared at I.C.U. gatherings. Thembinkosi Pewa recalls that the group

sang for Champion. This was a special request. Then spectators paid to enter the hall and watch us. This was just for entertainment over week ends. He did not pay any money. We did not expect money, in any case, because we were actually enjoying ourselves… Champion would buy food, cakes, etc. There was food for the singers which they had for a song, and the rest of the food was sold to the spectators. It worked the same way as the stokfel. There is a song about Champion, a complicated one. We did not compose it. It was composed by the Shooting Stars…The words went like this: “Thank you for your kindness, Champion. We thank you for your kindness, Mahlathi [praise epithet for Champion], the good that you have done for the Zulu. May God bless you.’ It was in praise of Champion. It was just like an imbongi [Zulu traditional praise poem], but we used to sing it. (Interview Pewa)

But political protest in isicathamiya did not stop with the demise of organizations like the I.C.U. Recorded evidence from the 1940s and 1950s indicates that political protest continued to be an integral part of isicathamiya despite the fact that most of these recordings never reached the pressing plants. Nevertheless, some songs that make overt reference to African nationalist ideology such as Linda’s Yethul’ Isigqoko (Take off your hat) (Gallo GE 887), were broadcast regularly from the Durban studios of the S.A.B.C. between 1943 and 1948 (Tracey 1948:v)

Take off your hat.

(Tracey 1948:53)

What is your home name?

Who is your father?

Who is your chief?

Where do you pay your tax?

What river do you drink?

We mourn for our country.

Other songs that were sold commercially included the following by The Pirate Coons:

Our home country has lost its values.

(HMV JP2)

Mother, it is now governed by foreigners.

Mayibuye IAfrika, another recording by Linda/s Evening Birds takes up one of the early nationalist slogans[41]For another version, sung by the Xolo Home Boys, see my record Iscathamiya, Interstate Music, Heritage HT 313, Side A, track 7..

Let us all say in unison: “Africa come back to us.”

(Gallo GB 3040)

We shall govern it on the day when it is back to us.

On a more down to earth level, away from the lofty rhetoric of African nationalism, some choirs addressed the complexities of daily life of those caught in the web of repressive laws. Thus it is possible for the social historian to reconstruct from a few records selected at random the typical sequence of events that characterizes the daily lives of black migrant workers harassed by pass laws and police.

An early recording by The Pirate Coons:

There is a great mystery among blacks.

(HMV JP 19)

I went to Johannesburg and saw the great mystery.

Police want a special pass.

Those who are not in possession of a pass, were well advised to heed the warning by the Dundee Wandering Singers:

Beware of the police van!

(Gallo GE 883)

And for those unfortunate ones who failed to produce the document, there remained only the option to chime in with the Dundee Wandering Singers’ lament:

Oh mother, we are under arrest.

(I.L.A.M. 773S)

The tradition of union-oriented entertainment and particularly isicathamiya performance resurfaced in the early 1980s with the rise of new militant trade unions. It is especially noteworthy that the imbongi tradition has been profoundly transformed in the hands of both isicathamiya choirs such as the K-Team and poets like Mi Hlatshwayo (Sitas 1987).

The K-Team, composed of Kellogs employees, specializes in the polished Ladysmith Black Mambazo style, and has recorded, among others, a song in praise of FOSATU leader Chris Dlamini:

Let us thank FOSATU for representing the black nation.

We thank you Dlamini and Maseko and the people who help you.

Even if it is tough, we will grab the hot iron.

We will persevere to the end.

Even though it is hard.

Brother Dlamini, persevere! We are right behind you.[42]Siyabonga Fosatu, Shifty Records, Fosatu Worker Choirs, L4 Shift 6.

In the attempt to map the political content of migrant workers’ expressive culture, it would be misleading to loose sight of political ideologies outside African nationalism. Since the collapse of independent African power and Zulu political autonomy, one of the focal points of opposition against the penetration of all spheres of life by an aggressive new social order has been Zulu nationalism. In a series of seminal articles, Shula Marks has shown how in the hands of the state, Zulu history, Zulu monarchy and the symbols of Zulu ethnicity “became a crucial part of the strategy of social control.” (Marks 1986a:112) The forceful formation of a working class based on a system of cheap and coercible migrant labour supplied by labour reserves and controlled by artificially restored “tribal” authorities was accompanied by attempts to bribe migrant workers with a belief in the legitimacy of traditional values. But there can also be little doubt about the skillful use the Zulu petty bourgeoisie, for their part, made of rural anti-capitalist traditionalism in order to broaden the base of their nationalism and ultimately to buttress their privileged social position (Marks 1986a:42-73).

Thus, in E Zintsukwini Zo Tshaka, an isikhunzi tune recorded in the early 1930s, the Edendale born music critic Mark Radebe, one of the early spokesmen of a “Bantu National Culture”, and his African Male Choir, gave Zulu nationalism and anti-colonial sentiment their own conservative, chauvinistic interpretation[43]See also the chapter on “Neo-Traditionalism and the ‘Proper’ Conduct of Zulu Women” in Marks 1986b:23-32. :

In the days of King Shaka we were rejoicing.

In the days of our forefathers nothing was troubling us,

because we were ruled by a wise ruler, King Shaka…

When he died, he said that we Zulus shall never be united,

and that we shall live scattered like birds.

We have already experienced this through the moving away

of married women from rural to urban areas.

What are wives doing here in the urban areas?

They behave like young girls and forget about their children.

(Columbia YE 12)

A more recent example of the ambiguity of anti-capitalist traditionalism is the following song by the Danger Stars which expresses resentment against oppression through allegiance to the Zulu king and “tribal” homeland leader Gatsha Buthelezi: