PATRIC TARIQ MELLET

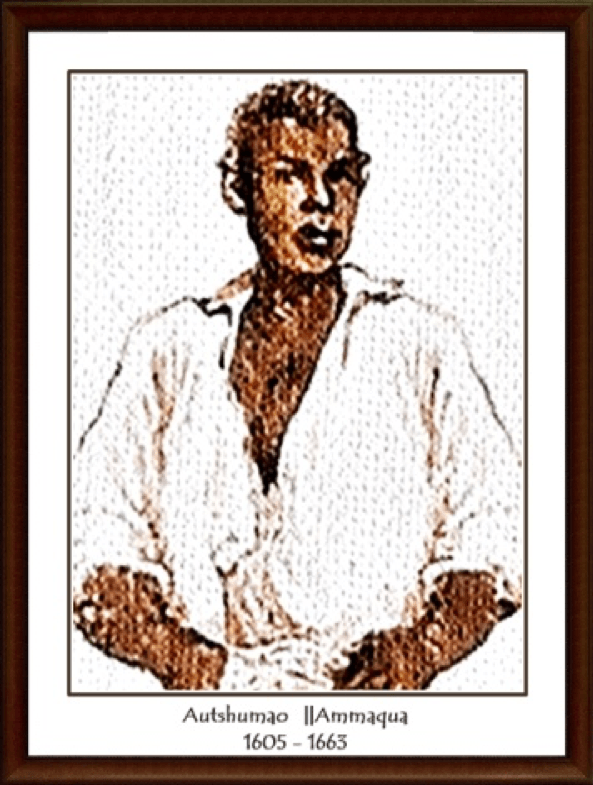

Autshumao – Between what is said and what is kept silent

between what I see and what I say

between what I say and what I keep silent

between what I keep silent and what I dream

between what I dream and what I forget

poetry

it slips between yes and no

Octavio Paz

In all the writings about Autshumao and his niece Krotoa there is both deft and crippling surgery of the truth, lobbing off important moments of his life, and there is blatant inaccuracy and misrepresentation. Like the Mexican poet Octavio Paz’s [1]Paz O; In Tapscott S; Twentieth-century Latin American Poetry – a bilingual anthology; Entre lo que veo y digo pg 262; Univ Texas Press; Austin (1996). description of where poetry resides, so is it the case when it comes to the history of the leading Khoi personality of his times and early founder of the proto port of Cape Town; indeed likewise with the history of the Khoi people as a whole.

Autshumao’s story well illustrates that the power of the individual in history at times is as powerful as that of the social group, sometimes more so, and that the trajectory of history is a dialectical relationship between these two forces. The individual too, though often politicised over time, most likely does not carry out an overtly or intended political or even social struggle. As far as what consciousness Autshumao and his niece Krotoa may have had about the bigger ramifications of their actions, with the absence of more record in their own voice, we simply don’t know. But from the little we do have we know that they did have a fair degree of consciousness for their times.

The individual, in this case Autshumao, however can carry the weight of a sudden transformative geo-political and economic moment in time and thus inadvertently he became a political statement of his time. What this story shows is that the true account presents an inconvenient truth for a colonial narrative that has dominated how both pre-colonial history and colonial history is framed. Perhaps the nearest that we will ever get to seeing a measure of Autshumao’s political-social consciousness in words, are the protest statements captured by the Commander’s scribe in his journal; particularly the statement regarding the injustice done to them, at the time when Jan van Riebeeck announced to them that they had lost their land to the sword.

As the stated most senior leader present at that meeting, the elderly Autshumao certainly understood the gravity of the moment and the Commander notes just how articulate, bold and feisty Autshumao was at that meeting.

In coming to get a perspective on Autshumao it is important to always keep in mind those writing about him and how their thinking was framed, their motivations and the social space which Nigel Penn[2]Penn N; The forgotten Frontier – Colonist & Khoisan on the Cape’s Northern Frontier in the 18th Century; pg 4; Ohio University Press; Athens (2005). highlights as that of the pdramatis personae. We should hear Penn’s caution for us to take cognisance of these factors when viewing historical ‘evidence’. He particularly shows us how the Khoi voice is suppressed and distorted because of the way the circumstance is viewed through a particular lens. The European imperialist and legal shaping lens has resulted in othering and dumbing-down the few Khoi voices that we have had the privilege to hear over the passing sands of time. The colonial record too, itself provides a degree of clarity, if viewed through a different lens. It is so blatant when reading the primary research texts against some of the key secondary writings, such as that of the American Richard Elphick, that much license has been taken in subjectively projecting a narrative that buys into the ‘primitivisation’ and ‘rascalisation’ of Autshumao and an unquestioning acceptance or identification with the assumed civilised ground in a struggle as recorded by Jan van Riebeeck and his scribe. Key pieces of information in the primary texts are left out of the story and in some areas there is a conjuring up of a storyline to create a coherent and favoured colonial narrative. The huge contradiction throughout the Autshumao story between two radically contrasting images of the man is lost on most researchers when on the one hand van Riebeeck projects Autshumao as a primitive, rascal beach bum and scavenger and on the other hand says of him:

“Besides we have been cruelly deceived in our interpreter Herri, whom we had always maintained as the chief of the lot, who had always dined at our table as a friend of the house and been dressed in Dutch clothes; besides also that from every fresh arrival he was provided with bags of bread, rice, wine, &c., by way of remunerating him for his services as interpreter.”[3]Van Riebeeck J; Precis of the archives of the Cape of Good Hope, Journal of Jan van Riebeeck Part II; pp

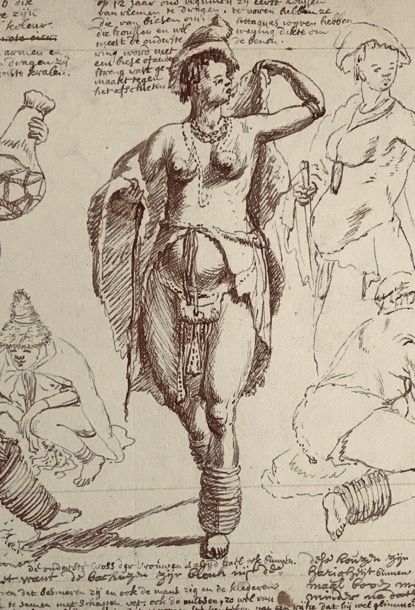

The description of an entrepreneurial Khoi man who dressed in European clothes and who engaged in multicultural practices leading a community of traders of mixed ancestry appears not once but throughout European writings over thirty years. Instead of this real man, the image presented by painter Charles Bell over 200 years later, when he imagined the first meeting between the Dutch led by Van Riebeeck and the Khoi led by Autshumao, is deeply embedded in the consciousness of all. The picture caricatures Autshumao as a startled ‘strandloper’ savage.

The story of Autshumao is in microcosm an illustration of everything that Walter Rodney [4]Rodney W; How Europe Underdeveloped Africa; Howard University Press; (1974). , the revolutionary African-in-Diaspora political-economy analyst from Guyana who was cut down in his prime by an assassin in 1980, conveyed in his book ‘How Europe underdeveloped Africa’ published in 1972. The struggle on the Table Bay shoreline at the Camissa River was fundamentally about the Europeans empowering themselves at the expense of African advancement. The under-development or usurping of the natural advancement of a strategic African port run by indigenous Africans was a key building block in Europe’s amassing power to itself in the race for global domination. The ruthless conquest of the ‖Ammaqua (Watermans) traders by appropriating their strategic resources, curtailing their access to clients, controlling the value they put on their products and services, stereotyping them as too primitive to participate in the new economy while destroying their ability to maintain control of their livestock-rearing agrarian economy, and Europeans engaging in physical annihilation of indigenes as the ultimate control, are all facets of Autshumao’s story. It’s the story of how Africa, actually by force, developed Europe, to invert Rodney’s phrase.

The sudden resurrection of a 5 year old cold-case against Autshumao in 1658 and the manner in which it was presented and evaluated in a summary kangaroo-court, resulted in a devastating life sentence on Robben Island that took Autshumao from hero status to zero. Accompanying this act was the confiscation of all of his wealth and the subjugation of all Khoi on the Cape Peninsular to the will of the Dutch VOC. It illustrates the centrality to Autshumao’s story of what the British cockney slang calls a ‘stitch-up’. It is this stitch-up that creates a haze around the story of Autshumao, and provided Jan van Riebeeck with an opportunity for vicious ‘payback’ and the opportunity to achieve by means of a treaty in one day, what Autshumao had prevented for six years.

The ‘stitch-up’ deprived Autshumao of the kind of life he should have enjoyed after the entrepreneurship, fastidiousness and hard work he had exemplified. Like any successful entrepreneur he knew what it was like to start over and over again until successful and as such he provides an amazing African role-model for our youth in the 21st century. The cold-case kangaroo-court brought an end to the co-dependent relationship that Jan van Riebeeck and Autshumao shared with each other. While most stories about Autshumao project Autshumao as a nuisance factor for Jan van Riebeeck, for most of Jan van Riebeeck’s time at the Cape he frequently required Autshumao’s assistance as much as he feared Autshumao’s pluck and influence on others. Autshumao too was a figure in history who was an African poised between West and East, poised between a pastoral economy and trading-service economy, and, by all accounts he handled this pressured pioneering role with valour and skill. The subjugation of Autshumao as an individual was also the first step in the conquest of South Africa by Europeans.

My 9th great grandmother, Krotoa (!goa/gõas – meaning a girl cared for by others) [5]Du Plessis M Dr; Dept of General Linguistics – Stellenbosch University ; Nama language consultation (2018). was the ward of my 11th great grand-uncle, the remarkable man of this story, known as Autshumao (‖Au-tsâma-ao meaning a man who swims around with fish… a likely reference to his travels to Java and his frequent boat trips back and forth to Saldahna Bay, Hout Bay and Robben Island [6]Van Sitters B; Khoi and San Active Awareness Group; Nama language consultation (2019)..). These two early Khoi figures have not been treated justly by history.

Circa 1630 Autshumao travelled to Banten (Bantam) in Java [7]Elphick R; Khoikhoi and the Founding of White South Africa; Chap 4 pp 83-66; Raven Press; Johannesburg(1985) with the English and, was able to learn some of the European languages, English in particular, as well as had exposure to the European traveller’s needs and ways of doing things. He was returned to Table Bay after this internship. One would not be wrong in interpreting this as a form of training or internship for a career in port servicing and trading and his entry into the chandler and stevedore business. It is important to put this fact up front as there has been a deliberate primitivising and dumbing-down of Autshumao by the colonial narrative which this paper will attempt to dispel.

Autshumao was regarded for some time by all European shipping stopping at the Cape to be at the service of the English as the postmaster and Governor of Robben Island according to a traveller [8]Mundy P. edt Sir Richard Carnac Temple Vink M (2003). The World’s oldest trade: Dutch Slavery and slave trade in the Indian Ocean in the 17th Century. Journal of World History (1967). P 327 The travels of Peter Mundy in Europe and Asia 1698 -1667 who recorded meeting him. From around 1638 [9] Elphick R; Khoikhoi and the Founding of White South Africa; Chap 4 pg 84; Raven Press; Johannesburg(1985) Autshumao assisted by his English clients moved back to the mainland Table Bay from Robben Island with his followers and went on to become the founder of the proto-port at Table Bay that over three centuries would grow into the city of Cape Town.

In 1652 all of Autshumao’s efforts were usurped when the Dutch United East India Company (VOC), authorised with powers of state by the Dutch States General, established a permanent settlement, took over the administration of port services, and the natural resources of the port. In the process of this take-over Autshumao was divested of his accomplishments, marginalised, humiliated and finally imprisoned just at the time that he had begun to recover his local stature. At the centre of this final assault on him by Jan van Riebeeck was the manipulation of a cold-case in 1653 involving the murder of a Dutch shepherd and theft of the VOC herd of cattle. A combination of the cold-case and a hostage-taking drama initiated by Jan van Riebeeck assisted by the interpreter Doman, was used to extract a peace treaty with the Goringhaiqua and Gorachoqua that effectively surrendered to Jan van Riebeeck everything that he had sought since 1652 but was prevented from achieving by Autshumao.

The initial establishment of a fort-come-refreshment-station for ships by VOC Commander Jan van Riebeeck soon became a Dutch colony for a century and a half and then it was conquered by the British. In the passage of time the Colony grew into the country known to the world as the Republic of South Africa.

In the crude attempts to imply that there was no conquest in 1652, Jan van Riebeeck distorted his first impressions of the local population by reducing the ‖Ammaqua traders by projecting them as non-permanent residents of Table Bay whom he labled ‘strandlopers’ or beachcombers with no permanent abode. This blurred the edges between the ǁAmmaqua [10]Valentijn F; Reference Map circa 1717 Cape showing the name ‖Ammaqua (Watermans); https://digitalcollections.lib.uct.ac.za (Watermans) and the Sonqua (Strandloopers). Later even Jan van Riebeeck had to grudgingly acknowledge that he made a huge mistake in his crude approach to evaluating Autshumao and his people and dumbing them down as ‘strandloper savages’: [11]Van Riebeeck J; Precis of the archives of the Cape of Good Hope, Journal of Jan van Riebeeck Part III; pp pp.85-86

“13 May 1656: It won’t do to say they are merely wild savages, what can they do? For the more they are known, the more impertinent they are found to be, and certainly not so savage and stupid as beasts. They will seize their chance whenever it offers, whilst their daily intercourse with the Dutch makes them sharper every day.”

There are more research records available on the lives of Autshumao and his niece Krotoa, including of their voices, than any other indigenous African in South Africa for at least a century and a half from 1652. Comparative written accounts of their lives by European contemporaries starting around 1630 also show that both personalities were frequently maligned, misrepresented and portrayed in a derogatory manner by some, inconsistent with other historical records which are quite complimentary and in contradiction with the former. Between this maligning and the popular notion during the European ‘enlightenment’ period of the ‘Hottentot’ as the ‘noble savage’ – part man and part beast, we have been bequeathed an over-amplified distorted story of Autshumao and his times. This account seeks to present an alternative appraisal. It is a shame that some in the late 20th century and in the 21st century in respectable academic institutions and in public life, such as the former Western Cape Premier Helen Zille [12]Mkhwebane B; PublicProtector Report – Zille’s colonialism tweet: The Full Public Protector’s Report; 13 June 2018, still beat the old ill-informed drums of colonial virtue and prowess vs indigenous inferiority and ineptitude, as loudly as they did in the past.

This account also, without dwelling on it, seeks to have the reader think about skewed European historical overlays on our primary story of Autshumao, which if not considered may disadvantage the enquiring mind from understanding motivations of the Europeans for using confusing identity labelling and boxing of the various peoples that they met at the Cape. Central to the games played with identities were the then popular stories, draped in mythologies, about two very real African kingdoms to the north – the Butwa (Butna) kingdom in northwestern Zimbabwe and the Mutapa kingdom straddling northeastern Zimbabwe and Mozambique.

The Dutch at the Cape were infatuated with these kingdoms (to which van Riebeeck refers in his journal) because they were known to be the source of gold and ivory.[13]Van Riebeeck J; Precis of the archives of the Cape of Good Hope, Journal of Jan van Riebeeck Part I; H.C.V. Leibrandt; p.380; Cape Town; W. A. Richards & Sons: (1897). They also feared the stories about the powerful people of these kingdoms and in the forefront of their minds tried to unravel the relationships between the indigenous people whom they encountered at the Cape, and those of the two northern kingdoms. They wrongly thought that the great Monomutapa was much nearer that it actually was in fact. Autshumao would also have known about the Mutapa stories from his travels and certainly would have played this as a card to his advantage when the Dutch tried to unravel lines of authority going inland of those they believed to simply be outriders of a bigger more powerful inland kingdom. In his journal Jan van Riebeeck says: [14]Van Riebeeck J; Precis of the archives of the Cape of Good Hope, Journal of Jan van Riebeeck Part III; H.C.V. Leibrandt; pg 8; Cape Town; W. A. Richards & Sons: (1897).

“the Chobonas, whose authority over this Cape people is still superior to that of Namana, and who are very rich in gold, and where it is supposed that the river Spirito Sancto lies, from which all the gold is taken to Mozambique, and not more than 120 or 130 miles to the north-east from this place. Their chief is evidently the Monomotaper, or Emperor of this distant region…… we would be pleased by your proceeding towards the Chobona or the town Monopatapa, which is rich in gold and the dwelling place of the Emperor, The land also is rich in gold near the river Spirito Sancto. You are to find out when meeting a nation, how they live, what chief they have, what clothes, what means of earning a living ; what their religion is, heir dwellings, their fortifications are and whether they have any reasonable government”

These kingdoms existed and there were old lines of trade right down south, but at the same time these also did not exist in the manner conjured up by the Dutch officials at the Cape. The two kingdoms were nowhere near only being 130 miles from Table Bay as believed by Jan van Riebeeck. For this reason the European terms – tribe, nation and kingdom are contradictorily used by the Dutch at different times quite inappropriately. Many today jump to all sorts of emphatic conclusions, and make wild claims based on the conjured up identity narratives gleaned from colonial writings which were highly impregnated with mythology and other European creations. The story of Autshumao cannot be understood without factoring in all of these under-currents.

The Khoi of the Cape Peninsular

The Khoi people at the time of this story are a very good example of micro social groups of herder societies that had not yet transformed into tight stratified social classes or formations such as a nation, kingdom or even a tribe (see discussion by Elphick on Hoernle). [15]Elphick R; Khoikhoi and the Founding of White South Africa; Chap 3 pp 43-56; Raven Press; Johannesburg (1985) / read with – Hoernle AW; The social organisation of the Namaqua Hottentots of Southwest Africa; pp 1-25; American Anthropologist; Jan – March 1925 The Khoi structures of governance also actually had more in common with modern day democracies at a time when Europeans were still very much in classical European feudal mode. The Europeans just could not get their heads around the flat governance and consultative (public participation) approaches of Khoi society. When the Bi’a (Head) or Kai Bi’a (Great Head) was told to order a member of his or her society to sell a bull to the VOC, the Dutch could not understand the response that the Bi’a had no power to order a person to do such an act.

The Khoi existed in the space of flexibility associated with clan and extended family behaviour. It was a natural manifestation of the kind of economic activity which was their mainstay – namely livestock farming, where the herding-ranching operated within a large spread of territory which they traversed along regular transhumance routes. Leadership within this context was multiple, non-hierarchical, less hereditary and based on strength and recognition of leadership qualities. [16]Elphick R; Khoikhoi and the Founding of White South Africa; Chap 3 pp 43-56; Raven Press; Johannesburg (1985) / read with – Harinck G; Interaction between Xhosa and Khoi; African Societies in Southern Africa; edt Thompson L; Heinemann (1967) / read with – Kolbe P; The present state of the Cape of Good Hope; Trs Guido Medley; Innys W ; London (1731). Because everyone was spread out over great distances, consultation was the name of the game when coming together to make decisions. There was no ambiguity about land ownership or territorial dominion as is often suggested by colonial historians. There simply was a different paradigm of thinking that put less emphasis on construction of permanent abodes and more emphasis on use of grazing land, herding routes, water access and seasonal habitation stations. In what became the Cape District and Stellenbosch District of the early colony there were basically four transhumance routes demarcated as being used by four different loosely organised Cape Khoi social groups, and one permanent trading station settlement. [17]Mountain A; The First People of the Cape; pp 42 – 46; David Philip; Cape Town (2003).

Two of the social groups, the Gorachoqua and the Goringhaiqua moved their herds near to each other between the western Diep River and eastern Berg River in an anti-clockwise transhumance route from around a furthest point about ten kilometres short of today’s Malmesbury and near to today’s Wellington where they spent their winters. In the long summers these two groups came into the Peninsula with the Goringhaiqua having their settlements along the slopes of what is today’s Southern Suburbs. The Gorachoqua had their settlements and routes through from Table Bay, Hout Bay, over the mountain into Retreat, Muizenberg, across the flats and through to today’s Stellenbosch. But the two groups which once were one group and again later after their expulsion from the Peninsular by the Dutch united again – were often alongside each other rather than rigidly separated. Together they numbered around 5000 people.

The Cochoqua social group was of much larger numbers than the other groups and more wealthy in livestock – cattle and sheep. They had more tribal coherence than the other groups and covered a large area starting around the west coast mouth of the Berg River, northwest of Saldahna Bay. Their transhumance route travelled southwards from Saldahna Bay, turning north around today’s Malmesbury until they reached the Berg River again and followed the trajectory of the Berg River back to Vredenberg.

Then there were the Sonqua and Ubiqua hunter groups related to the San (│Xam and !Kun) to which some outcast or drifter Khoi, who were also disparagingly referred to by other Khoi as Goringhaicona (our kin who left us), had become attached. These Sonqua also at times opportunistically kept some cattle usually as a result of raiding the Khoi. The Sonqua largely lived in the northwestern and central areas across the Berg River, but among the Sonqua were those who ventured to the coast and engaged in a line-fishing way of life and living off other seafood and roots. They combed the beaches moving backward and forward along the West Coast as far south as Bloubergstrand and the Salt River. It was these Sonqua who were the real ‘strandlopers’, to use the word that was indiscriminately and manipulatively introduced by the Dutch. Further northwest were lots of micro-groups of (Chari) Griguriqua who were client herders of the numerically and livestock strong Little (N)amacqua peoples whose territory stretched far up to mesh with the Greater Namaqualand and the Gariep and Namibia.

From August 1685 to 20th January 1686 Simon van der Stel made a trip to little Namaqualand that requires scrutiny. He kept a journal entitled “Simon van der Stel’s Journal of his expedition to Amacqualand 1685 t0 1686.” The term “Amacqualand” was changed in later centuries to read Namaqualand showing that the people van der Stel referred to in his text from just below the Berg River onward as Amacqua were Namaqua. However on Valentines map just west of Saldanha Bay too far south to be (N)amaqua he locates a people called and spelt Ammaqua (Water People) who clearly are related to Kamesons (Water People).

Van der Stel notes that the (N)amacqua captains that he first on the trip from 6th October 1685 shared their kraals with the //Cummison (Kamesons). These people according to Simon van der Stel’s journal protested that they were not Sonqua (San) and their name, //Cummison translates as “Water People”. On the arrival of the Europeans there was hostility and tensions toward them by the Kameson and (N)amacqua who went to great length to mislead the Europeans as to the whereabouts of their kraals even when severely abused and punished. This clearly reflected earlier experiences between these peoples and the Europeans. The Khoi leaders met and named as Captains were identified by the Dutch as – Nonce, Joncker, Rabi, Oedesson, Harramoa, Otwa, Habij and Ace.

Saldanha Bay and surrounds had a fluidity of identity as the result of the territory absorbing refugees from European aggression in the Cape District from Jan van Riebeeck’s time. One such refugee group were the Table Bay //Ammaqua of Autshumao who settled not far from Saldanha Bay among their Cochoqua kinfolk after being driven from the Cape Peninsula. This is not the (N)amacqua that van der Stel talks about but likely to be kin of the Kamesons. As will be seen in this story, Schoemann tells us the story of how the Table Bay Watermans escaped van Riebeeck’s bounty hunters to make their way to Saldanha Bay as did Autshumao after escaping from Robben Island. This chosen place of refuge connects to the fact that Krotoa’s sister, Autshumaoa’s other niece was married to the leader of the Cochoqua.

To the east, the numerically and livestock strong Cape Khoi groups with much stronger tribal coherence were the Chainouqua, Attaqua, (outen) Niqua, Hessequa and the Gonaqua (with Hoengeyqua, Guriqua, Damara and Gamtoos clans). [18]Elphick R; Khoikhoi and the Founding of White South Africa; Chap 3 pp 49-53; Raven Press; Johannesburg (1985). The latter Gonaqua were also partly incorporated into the southern Xhosa-Khoi people known as the Gqunukhwebe. The Xhosa also had strong familial relationships with the Khoi right down to the Chainouqua where it was difficult to separate Xhosa from Khoi. Before contact with the Europeans there were already 11 Khoi tribes and clans, including the only known Khoi kingdom, that of the Inqua, which had merged into the amaXhosa. [19]Peires J; The House of Phalo – A History of the Xhosa People in their days of Independence; pp 18-31; Johnathan Ball; Johannesburg (1981). All of the Khoi, the Xhosa, Thembu, Sotho, Tswana ultimately had historical descent linkages to the Khoi and Kalanga that had emerged on the road to the establishment of the first multi-ethnic state in South Africa at Mapungubwe, which then gave birth in a progression to the Great Zimbabwe, Butwa, Mutapa, Rozvi and Tsonga kingdoms. Trade routes [20]Elphick R; Khoikhoi and the Founding of White South Africa; pp 1 – 22; pp 62-68; Raven Press; Johannesburg (1985) / Read with – Deacon HJ & Deacon S; Human Beginnings in South Africa – Uncovering the secrets of the Stone Age; pp 177-178; David Philp; Cape Town; (1999) / read with Elphich R; KhoiKhoi and the Founding of white South Africa; pp57-68; Raven; (1985) 1-22; pp 62-68; / read with – Huffman TN; Mapungubwe and Great Zimbabwe: the origin and spread of social complexity in southern Africa. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, 28, 37–54; (2009) – read with – Huffman TN; Mapungubwe and the origins of the Zimbabwe culture. In M. Lesley & T.M. Maggs (Eds.), African naissance: The Limpopo Valley 1000 years ago (South African Archaeological Society Goodwin Series 8), pp. 14–29; (2000) / Read with -Huffman T N; Ceramics, settlements, migrations; The African Archaeological Review, 7; pp.155-182 from those origins reached all the way down to Table Bay and from those northern kingdoms they reached out to the world via Mozambique ports – to Arabia, India, Southeast Asia and China. It is unfortunate that knowledge of African social history, particularly that of South Africa, has been blotted out by colonial academia that has placed ‘race’ theories and the antiquity archaeology of Africa as all that existed before the arrival of the Europeans in South Africa. South African museums are void of any due coverage of pre-colonial African history and simply carry archaeological exhibits of iron-age and stone-age. During the first half of the 17th century in two stages a new formation established itself permanently in Table Bay, as did other independent Khoi livestock farmers such as the wealthy Ankaisoa. First under the leadership of Xhore (Coree), a group of followers from the Gorachoqua and Goringhaiqua began to service the European shipping needs. [21]Cope J; King of the Hottentots; Howard Timmins; Cape Town (1967) / Read with – Elphick R; Khoikhoi and the Founding of White South Africa; pp 78 – 82; Raven Press; Johannesburg (1985). After Xhore’s death when this activity fell apart, Autshumao arose with a following to take this activity to a new more organised level. These people called themselves ‖Ammaqua and the Europeans called them Watermans. Colonial historians seem to deliberately blot out this formation and replace them with those they refer to as scavenger ‘strandlopers’.

The micro-context – ‘Strandlooper’ vs ‖Ammaqua founder of the Port of Cape Town?

We need to delve a bit into the core issue of identities at the Cape if we want to understand Autshumao and about his demise when a hastily convened court of the VOC Council of Policy used a cold-case in 1658 to summarily try him and incarcerate him on Robben Island.

It is perhaps important to first note the different formations of indigenous peoples in the geographical circle of influence of the Dutch colonials in the Cape of Good Hope during the mid-17th century at the Cape of Good Hope. In doing so, I differ with Richard Elphick’s [22]Elphick R; Khoikhoi and the Founding of White South Africa; pg 94; Raven Press; Johannesburg (1985). somewhat contradictory labelling and description of Autshumao’s people as ‘strandlopers’ and his presumptions about this group. Elphick [23]South Elphick R; Khoikhoi and the Founding of White Africa; pg 49; Raven Press; Johannesburg (1985). also adds to the confusion by re-labelling those that van Riebeeck called ‘Capemen’ as ‘Peninsular Khoikhoi’ but at the same time correctly underlining that in 1652 – 1653 when Jan van Riebeeck in his journal first spoke of the Saldanhars he meant all cattle-keeping Khoi on the Cape Peninsular and its surrounds – Goringhaiqua, Gorachoqua and Cochoqua. The latter were much further away rather than on the Cape Peninsular but later Jan van Riebeeck would refer to them as the ‘true Saldanhars’. Why all of this fancy footwork with identities?

We need to navigate different terms for the same people, lest we come to wrong conclusions. Another term in use is the term ‘Goringhaicona’ [24]Elphick R; Khoikhoi and the Founding of White South Africa; pg 94; Raven Press; Johannesburg (1985). which did not denote a tribe at all and was used disparagingly by Khoi tribes to refer to ‘our kin who left us’ and it was applied not only to the ‖Ammaqua [25]Valentijn F; Reference Map circa 1717 Cape showing the name ‖Ammaqua (Watermans);https://digitalcollections.lib.uct. (Watermans), but also to a number of independent livestock farmers as well as to less fortunate outcasts who had joined the Sonqua [26]Elphick R; Khoikhoi and the Founding of White South Africa; pp 1 – 22; pp 62-68; Raven Press; Johannesburg (1985) / read with Van Riebeeck R; Van Riebeeck J; Precis of the archives of the Cape of Good Hope, Journal of Jan van Riebeeck Part I; pp 38-39 H.C.V. Leibrandt; p.; Cape Town; W. A. Richards & Sons: (1897). migrant line-fishermen combing the beaches. It was a term that simply separated those who lived under the tribal umbrella and authority and those who don’t. Much licence has been taken by some academics around the demographics of the time which treat statements as rigid fact that emanate from van Riebeeck’s journal as opinions, assumptions and perspectives of the VOC Commander which change or modify over the duration of the journal as experience rather than hearsay influences the capture of information.

This distortion is most glaring around the term ‘strandloper’, a slang term applied indiscriminately by Jan van Riebeeck and specifically is contradictorily pinned onto two very different peoples – the ‖Ammaqua (Watermans) traders and the Sonqua line-fishermen and straggler Khoi who joined them. Elphick goes further in saying that it can be applied to deserters, outcasts, beggars or scavengers and any who found themselves outside of the tribes. At times however he projects the same term to be a tribe and misuses the term ‘Goringhaicona’ to sometimes only refer to Autshumao’s people as though this was a tribe called Goringhaiqua. In the 21st century we now too have people trying to resurrect or revive some entities as though these are all separate tribes, yet they simply are often just labels for the same people pinned onto them by Europeans for narrow political and legal ends that had everything to do with legalising land dispossession. The term ‘strandloper’ was a term of disempowerment, marginalisation and dumbing down. Put another way it is a tool of dispossession.

Here it is important to clarify the demographics of African society in what would quickly became the Dutch Cape District after 1652. By the beginning of the new 18th century the cartographic work of Valentijn [27]Valentijn F; Reference Map circa 1717 Cape showing the name ‖Ammaqua (Watermans);https://digitalcollections. still uses both terms – ‖Ammaqua and Goringhaicona denoting different peoples, but show that they relocated just a little further up the West Coast in the case of the latter and right up beyond Saldahna in the case of the ‖Ammaqua by 1717. At the end of this story we will see why this was the case. An inset map detail within Valentijn’s larger mapped area is a more accurate showing of how by that time the European settlement had totally removed the early Khoi societies. The fact that these names are still used in circa 1717 indicate that either the Peninsular groups or the memory of them was still alive in some way – most likely as Khoi who had been put to flight rather than submit to pacification. In the absence on the map specifically of the Sonqua (San fishermen mixed with Khoi outcasts) it can only be assumed that when referring to Goringhaicona on a map in 1717 there was either still fresh memory of so-called ‘strandlopers’ or there were still some in existence, but this clearly was not the descendants of Autshumao who had moved to Saldahna after the devastating attack by bounty-hunters during the First Khoi-Dutch war in 1659. [28]Schoemann K; Seven Khoi Lives – Cape biographies of the seventeenth century; pp 68-69; Protea; Cape Town; (2009). Enough evidence exists in the journal of Jan van Riebeeck to illustrate that Autshumao had a rear-base in the vicinity of Saldahna Bay under the patronage of the Cochoqua.

In 1652 there were three groupings that engaged with Jan van Riebeeck, as per a record of a dinner conversation [29]Van Riebeeck R; Van Riebeeck J; Precis of the archives of the Cape of Good Hope, Journal of Jan van Riebeeck Part I; pp 38-39 H.C.V. Leibrandt; p.; Cape Town; W. A. Richards & Sons: (1897). between him and Autshumao and these effectively practiced three economies at the Cape at the time of first European incursion as colonists – namely hunting-fishing, livestock framing, and trading and servicing. Autshumao was the leader of the latter. These have already been mentioned as the Sonqua line-fishermen wandering community that operated along the beaches from the northern west coast and sometimes as far south as the mouth of the Salt River – ‘strandlopers’. The second group were the ‖Ammaqua (Watermans) traders who were a micro-community, residing in Table Bay at the outlet of the freshwater (‖Amma) Camissa River into the sea and who placed a high value on water as the much needed resource by ships. They are a distinct group with their own unique history from those called ‘strandlopers’. The third group that he notes are those that he calls Saldanhars or Capemen. At this time this term simply meant all livestock keeping Khoi on the Peninsular and immediate surrounding district stretching up the West Coast across the bay and up to what they later called the Hottentots Holland Mountains – largely the Gorachoqua and the Goringhaiqua. The term Saldahna at that time was still the Portuguese term for Table Bay, hence it refers to what Elphick labelled as Peninsulars. After the colony was established, the Dutch emphasised the ‘true Saldahna’ and ‘true Saldanhars’ referring to Saldahna Bay and the Cochoqua people.

This earliest demographic summary arose in the context of a dinner held at the Fort between the Van Riebeeck [30]Van Riebeeck R; Van Riebeeck J; Precis of the archives of the Cape of Good Hope, Journal of Jan van Riebeeck Part I; pp 38-39 H.C.V. Leibrandt; p.; Cape Town; W. A. Richards & Sons: (1897). family and the family of Autshumao. It is interesting to read the entire conversation as recorded in van Riebeeck’s journal rather than the commentaries of historians like Elphick who put their own overlay that sometimes misrepresents what is actually said. For example – Jan van Riebeeck notes that from his discussion with Autshumao, in the English language, that the ‖Ammaqua (Watermans) were a micro-community residing in Table Bay numbering around 50 people at most. Others note that this community consisted of eighteen men and their wives and children, the core of who were Autshumao’s own family. This illustrates a contradiction in Elphick’s work where he suggests that there was no kinship base to Autshumao’s people, when the facts point to its core being Autshumao, his three wives, his niece and her mother, his sons and their wives. This familial core [31]Robertson, Delia; The First Fifty Years Project. http://e-family.co.za/ffy/g17/p17230.htm included Autshumao’s son Arre, wife and children, another son Khonomao Namtesij (Claes) and his wife and children, Krotoa the niece of Autshumao, Hemoa Khatimaἅ, Hum Tha Saankhumma, Khamy, Lubbert, Beijmakoukoa Danhou, Boubo and Thoe Mak Koa.

Jan van Riebeeck references the European term ‘Watermans’ and not the indigenous name ‖Ammaqua, in the same way that he uses ‘Herri’ and not the indigenous name Autshumao. He does however note that Autshumao and his people refer to themselves as Watermans, and thus this is not an imposed name. The indigenous term ‖Ammaqua for this group is used by Valentijn his early detailed map of the Cape Colony circa 1717. The maps of Valentijn and others of those times are well known more for their beauty than being absolutely historically or geographically correct, hence one uses them with some caution for cross referencing. But what is useful however is that these maps do give us the names of the various indigenous African people of the Cape District with more clarity than can be found elsewhere and they offer some tell-tale information as to what happened to various peoples after the 1659 war. The assumption was that all the Peninsular peoples disintegrated at that time and either were pacified or became identity-less refugees.

The ‖Ammaqua (Watermans) were the shoreline frontier community of traders and facilitators who assisted the constant stream of ships making compulsory refreshment stops at the Cape of Good Hope. They were not ‘strandlopers’ scavenging on the beaches. Colonial historians have tended to go along with van Riebeeck’s non-recognition of the actual business role of Autshumao and his people by equating them with the beach-comber Sonqua and stragglers who joined them from other Khoi groups, regardless of the fact that in van Riebeeck’s journal he notes that Autshumao identified the Sonqua or ‘Strandloper’ fishermen as his enemy. Indeed Autshumao pleaded with van Riebeeck to assist him against the fishermen. It is these contradictions in the primary texts that are important to note before we proceed further with the story of Autshumao. The frequency of the references in Van Riebeeck’s journal of linking Autshumao and the Watermans (‖Ammaqua) makes it indisputable that this was the expressed identity of Autshumao and his people and not ‘strandloper’ or ‘Goringhaicona’.

The macro-context – keeping the eye on the bigger African picture

As much as there needed to be clarity on the micro-context it is also important to gain some clearer picture about bigger context of Africa and the relationships of its people right down south to the rest of the continent and African people across the continent. The European has always projected the south as almost being a different and unrelated territory to the rest of Africa.

Colonial/Apartheid academia from various disciplines rigidly separated the Africans of South Africa into ‘race-silos’ that coincided with supposed rigid economic modes of sustaining themselves. So we were told that there were hunter-gatherers who made up a ‘race’ called San or Bushmen; then we were told that there were herders who made up a ‘race’ called Khoi; and finally farmers with metallurgical skills who were a ‘race’ called Bantu and there was no mixing between these people who were mortal enemies. The latter we were told were alien invaders who suddenly swooped down from Nigeria and Cameroon via the Great Lakes in Central Africa in the fifteenth century.

This paradigm of thinking is part of the bedrock of Apartheid that still dominates the historical information and discourse space in South Africa. Conveniently it places the European colonist in a position where they supposedly came to the rescue of the ‘brown-races’ against the marauding sub-Saharan ‘black races’.

A somewhat different story unfolds when one takes a multi-disciplinary approach to African social history, ethnic history, linguistic history, genetics, paleo art, archaeology, anthropology, oral history and so on. There really were no ‘three’ moulds ever. As much as there were hunters, there were herder-hunters and fishermen-hunter-herders; herders too were often engaged in both hunting and farming; and as much as there were farmers there were farmer-herders and hunter-herder-farmers. As much as people gathered roots, bulbs, leaves, fruits there were gatherers who tried their hands at cultivation, and farmers who foraged at times too because that is how domestication of crops started. While there were broad modes of sustenance and production, the notion of solid walls locking peoples into such modes of living for all time and these coinciding with notions of identity constructs called ‘race’, and with ethnicity and cultural practices has no sound academic/scientific basis.

The conflation of broad families of languages and the notion of ‘race’ that has then been laid on the three silos became an aberration in its next step. Those who thought in this manner began a debate on whether ‘San/Bushmen’ and ‘Khoi/Hottentot’ were two separate so-called ‘races’ or one. In the beginning of the 20th century a German zoologist dabbling in anthropology decided that there was a single Khoisan ‘race’ that was part human and part beast. He argued that this race was contaminating the human race and should be exterminated. This ‘Khoisan’ line of thinking was soon taken up by Isaac Schapera who also expounded an erroneous linguistic theory that found resonance with the racist theories of Leonard Schultz. [32]Schultz L; Aus Namaland und Kalahari; Berlin (1907) / Read with – Olusoga D & Erichsen C W; The Kaiser’s Holocaust – Germany’s forgotten genocide and the colonial roots of Nazism; pg 205Faber & Faber; London (1988).

Schultz was the creator of this ‘Khoisan’ notion which spread like wildfire within academia. He had carried out live experiments on the Nama in concentration camps in Namibia during the genocide by the Germans on the Nama and Herero peoples. Everything in the studies available to us shouts out that while there are broad families of ethnicities that can be loosely called ‘San’ and ‘Khoi’, they are neither absolute or rigid ‘races’ nor are they simply a single so-called ‘race’ or people or nation called ‘Khoisan’. Yet academia continues in this vein, disregard the protest of the San communities in particular. There never was nor is there a ‘Khoisan’ people or nation. It is a complete fabrication. There are distinct communities referred to as the San family of peoples with a particular history, heritage and culture, and distinct communities referred to as the Khoi family of peoples with their particular history, heritage and culture. Why it is further important to note this distinction is that among those who persecuted and committed genocide against the San family of peoples, record shows that the Khoi were also perpetrators of these crimes

Likewise there are more than 400 ethnicities that connect to the Bantu family of languages and there are no absolute rigid walls between Bantu language speakers and ethnic groups who are San or Khoi. Bantu too are not a people, nation or ethnic group. While predominantly ‘San’ engage as hunter-gatherers to sustain themselves there are those who also engaged in herding and farming. Not all ‘San’ peoples are nomadic without permanent abode and neither are all Khoi herders and all Bantu language speakers farmers. It is also not the culture of any people to be locked forever in one moment in time and stereotyped. It is very important that we extricate our enquiry on the past from racist theory and framing.

Pseudo-scientific reasoning imbued with colonial patronisation and notions of the noble savage, and civilised vs un-civilised in a hierarchy of worth based on ‘race’ has grievously damaged our ability to have discourse in a meaningful way between those who were subject of this thinking and those who subjected people to this reasoning. The Sonqua line-fishermen labelled ‘strandlopers’ have been made subject to this overlord debate and this occurred because Jan van Riebeeck and the VOC were wrestling with how they could in international law make the case of occupying land lawfully as no settled people in their opinion had just claim to it. The term ‘Khoisan’ was an attempt to assimilate diverse peoples into a common inferior identity that could be marginalised and deprived of their rights – it was no different to the use of the term ‘strandlooper’. Right into the late 19th century hunting licences were still being issued to hunt ‘Bushmen’ (San) along with kudu and springboks. That is how far the manipulation of identity and the use of dehumanisation tactics was practiced by Europeans on Africans.

However as contradictions got the better of him, Jan van Riebeeck dispensed with the approach of trying to intellectually obliterate identities and fell back on the law of conquest at the time of Autshumao’s incarceration in 1658 on the basis of the resolution of the cold-case of 1653. The VOC Chamber of 17 however, had tried to avoid a war scenario and still preferred a legal-intellectual approach rather than the ‘by the sword approach’ and, were annoyed with Jan van Riebeeck’s mishandling of Autshumao and relations with the Watermans which they believe was the real reason for the start of the first Khoi-Dutch war. [33]Elphick R; Khoikhoi and the Founding of White Africa; pg 111; Raven Press; Johannesburg (1985). The VOC changed the Commander at the Cape within 18 months after the conflict situation had quietened down. But the clock could not be turned back and the trajectory remained ‘forced removals’ – the legacy of Jan van Riebeeck.

At his dinner conversation recorded in his journal on 13 November 1652, Jan van Riebeeck [34]Van Riebeeck R; Van Riebeeck J; Precis of the archives of the Cape of Good Hope, Journal of Jan van Riebeeck Part I; pp 38-39 H.C.V. Leibrandt; p.; Cape Town; W. A. Richards & Sons: (1897). while entertaining Autshumao and his family used the opportunity to elicit information and verify information. Jan van Riebeeck seeks to give the impression that the tiny community of Watermans were located in three different locations mainly behind Table Mountain and behind Lions Head and not just in Table Bay indicating that they were just another branch of wandering beachcombers. It is most unlikely given how tiny the ‖Ammaqua community was that they would split up in this manner and it reinforces the notion that van Riebeeck was trying to project that there was no prior claim to Table Bay or the port because the Watermans were from elsewhere. As their name indicates they are associated with fresh drinking water and this locates them at the river in Table Bay. It also does not connect them to seawater which has another name in the Nama, !Ora and Khoekhoegowab languages. There is no ambiguity.

Autshumao’s community and his own innovation and entrepreneurship has also got to be seen in the context of pre-colonial social history of the peopling of Southern Africa at a time before the creation of borders in Southern Af Rui Ka by the Europeans.

The name Af Rui Ka is said to go back to ancient black kingdom of Kemet, later known as Egypt, and its meaning is roughly ‘the birthplace of humanity’. [35]Massey G; A book of the beginnings Vol 1; (1881). Later Greeks, Romans and Arabs all developed variants of the name Africa and it withstood the sands of time. Humanity is said to have first emerged along the east coastline of Africa, spread to the rest of Africa and across the world. Migration thus became part of the dna footprint of humanity and wherever humans migrated and settled, fresh drinking water – ‖amma, was always central to human habitat for without drinking water humans would die.

Like in most parts of the world, human settlements in Southern Africa occurred along major rivers and intersections of the rivers and the ocean. The peopling of Southern Africa firstly goes back to antiquity and then secondly to another set of events from the last millennium BCE. Two of the major waterways – the Zambezi and the Limpopo around the confluence of the Shashe and Limpopo, were the habitat of peoples whose origins go back to antiquity as micro social formations evolving from the first homo-sapiens. These were the Khwe, Tshwa, Tshua or abaTwa hunters (San peoples) respectively. [36]Le Roux W & White A edt; Voices of the San; inside cover, locations of San of Southern Africa; Kwela Books; (2004). Such San communities of various ethnicities also were to be found all over South Africa as distinctly different ethnic communities with different names and micro sub-cultures.

From around 1000 BCE a slow migratory drift [37]Hall M; Farmers, kings and traders: the peoples of southern Africa, 200–1860. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. (1990) M. Hall, The Changing Past: Farmers, Kings and Traders in Southern Africa, 200 –1860 (Cape Town, David Philip, 1987), p. 31. took place, first of descendants of East African herders of Nilotic origins, shortly followed by multi-ethnic farmers with metallurgical skills from Angola (Kalundu cultures), the Great Lakes (Nkope cultures) and East Africa (Kwale cultures). [38]Huffman T N; Ceramics, settlements, migrations; The African Archaeological Review, 7; pp.155-182 ; Map Figure 3 New EIA assignments. Pg 161; The latter three cultures, noted by their different pottery designs, spoke languages that can be noted as being part of the 400 ethnicities that make up the family of Bantu language speakers. Their DNA forms branches of Sub-Saharan African dna spread over broad regions of much of Africa. Archaeologists [39]Binneman J, Webley L & Biggs V; Preliminary notes on an early iron age site in the Great Kei River Valley, Eastern Cape; South Africa Field Archaeology – Issue 2; 1: pp 108-109; (1992) / read with – 44 Steel J; First Millinnium agriculturalist ceramics of the Eastern Cape, South Africa – An investigation; Unisa MA; (2001). demonstrate that such groups were present at various places in South Africa by 350 CE and as far south as East London by 650 CE engaging in farming, metallurgy and ceramic production.The descendants of the herders who originally left East Africa hundreds of years before, engaged with the Tshua or Tshwa (abaTwa) hunters around 200 BCE and it is from this engagement that the Khoi hunter-herder people emerged and would migrate to Botswana and Namibia, and all along both sides of the Limpopo as far as the Indian Ocean, where they became one of the foundation peoples of many new societies that would spring up. [40]Sadr K; Invisible herders – The archaeology of Khoekhoe pastoralists; School of Geography, Archaeology and Environmental Studies, University of the Witwatersrand; Southern African Humanities Vol. 20 Page 192;Pietermaritzburg; (2008) / read with – Schlebusch C; Lactase persistence alleles reveal ancestry of Southern African Khoe pastoralists; Uppsala Bio Life Science Pathfinder; [journal/ April] (2014). Read with – Carina M. Schlebusch, Pontus Skoglund, Per Sj ̈odin, Lucie M. Gattepaille, Dena Hernandez, Flora Jay, Sen Li, Michael De Jongh, Andrew Singleton, Michael G. B. Blum, Himla Soodyall, and Mattias Jakobsson. Genomic variation in seven Khoe-San groups reveals adaptation and complex African history. Science (New York, N.Y.) , 338(6105):374–379, October 2012./ read with – Eastwood EB & Smith BW;Fingerprints of the Khoekhoen: Geometric and Handprinted Rock Art in the Central Limpopo Basin, Southern Africa; Goodwin Series, Vol. 9, Further Approaches to Southern African Rock Archaeological Society Art ; pp. 63-76; (2005) / read with – Smith BW & Ouzman S; Taking Stock: Identifying Khoekhoen Herder Rock Art in Southern Africa; Current Anthropology; 45:4, pp 499-526 Univ Chicago Press (2004) South African Archaeological Society / read with – Schlebusch C; Lactase persistence alleles reveal ancestry of Southern African Khoe pastoralists; Uppsala Bio Life Science Pathfinder; (2014).

All South African tribal identities today include Khoi roots. At the western Limpopo on the south side, the Tshua and the Khoi were joined by the migratory drift of farmers around 350 CE. Multi-ethnic and multi-cultural sets of societies emerged in a progression from 350 CE until 900 CE. These cultures include those identified by archaeologists, by means of the different types of fragments of their cultures left as markers, as – Ziwa, Zizho and finally Kalanga cultures. [41]Huffman TN; Mapungubwe and the origins of the Zimbabwe culture. In M. Lesley & T.M. Maggs (Eds.), African naissance: The Limpopo Valley 1000 years ago (South African Archaeological Society Goodwin Series 8), pp. 14–29; (2000). / read with – Schoeman MH & Pikirayi I: Repatriating more than Mapungubwe human remains: Archaeological material culture, a shared future and an artificially divided past; Schoeman, Department of Archaeology, School of Geography, Archaeology and Environmental Studies, University of the Witwatersrand; Pikirayi, Department of Anthropology and Archaeology, University of Pretoria;https://repository.up.ac.za/ / read with – Calabrese J.A; Interregional interaction in southern Africa: Zhizo and Leopard’s Kopje relations in northern South Africa, southwestern Zimbabwe and eastern Botswana, AD 1000 to 1200. African. Archaeological Review 17(4): 183–210. (2000). Break-away migrants from this progression moved into Botswana, and also down to today’s Gauteng, to Lesotho, Free State, Northern Cape and to as far down in the Eastern Cape as East London by 650 CE. [42]Binneman J, Webley L & Biggs V; Preliminary notes on an early iron age site in the Great Kei River Valley, Eastern Cape; South Africa Field Archaeology – Issue 2; 1: pp 108-109; (1992) / read with – Steel J; First Millinnium agriculturalist ceramics of the Eastern Cape, South Africa – An investigation; Unisa MA; (2001). From this scenario Khoi and proto-Kalanga thrived alongside each other as farmer and herder societies but these in their migrations had displaced San societies like the Ju, !Kun and ǀXam also known as abaTwa who had been the surviving societies that go back to the earliest homo sapiens in the region.

The same happened in KZN [43]Francis M; Silencing the past: historical and archaeological colonisation of the Southern San in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa; Anthropology Southern Africa, 32(3-4), 106–116.https://doi.org/10.1080/23323256.2009.11499985; where early Khoi herder and the migratory drift of early farmers displaced the ǀXegwi (San) also known as abaTwa. By 1050 CE migrant Khoi societies had reached the Western Cape by both east and west routes. [44]Elphick R; Khoikhoi and the Founding of White Africa; pp 3-42; Raven Press; Johannesburg (1985). Again these Khoi migrants displaced the original Cape San people who had lived in the coastal regions [45]Stow G; The Native Races of South Africa: A history of the intrusion of the Hottentots and Bantu into the hunting grounds of the Bushmen – the aborigines of the Country; Struik; Cape Town (1964). . By the time of European incursion 600 years later most Cape San of Eastern Cape and Western Cape had be pushed into the drier and mountainous Central Cape also known as ǀXamka or Bushmanland. After the first millennium the formation occurred of the first multi-ethnic and multi-cultural South African state at Mapungubwe where San, Khoi and Kalanga (Bantu language speakers) lived in a stratified society and where the San had a niche role in Royal or upper class society as rainmakers and spiritual guides.

Parsons [46]Parsons N; A new history of Southern Africa; pp25-36; McMillan; (1980). shows us how this first state gave rise to successive states at Great Zimbabwe, Thulamela, Butwa, Mutapa and elsewhere opening up 700 years of kingdom formations. These occurred as a result of circular migrations within Southern Africa, supplemented by continued slow migratory drifts. In the first few centuries of the second millennium Tswana, Sotho, Pedi, Venda, Ndebele, Tonga, Tsonga, Shona and Shangaan societies emerged from this as did northern Nguni societies such as the Swazi, Hlubi, Ndwandwe, Mthethwa, and Zulu peoples.

But many super societies in the form of kingdoms and even an empire emerged in this process. The northern Nguni language speakers were not a monolithic invader people who suddenly arrived in South Africa as colonial historians have claimed but rather a South African people which emerged from complex old circular micro migratory drifts and developments that brought San, Khoi, Kalanga, Bokoni peoples, Tsonga, Hlubi and Rozvi eMbo together to form the many kingdoms in the area.

Later Shaka from the tiny Zulu clan carried the earlier traditions and innovations of the maMbos of the Rozvi Empire. [47]Huffman TN; Mapungubwe and Great Zimbabwe: the origin and spread of social complexity in southern Africa. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, 28, 37–54; (2009) – read with – Huffman TN; Mapungubwe and the origins of the Zimbabwe culture. In M. Lesley & T.M. Maggs (Eds.), African naissance: The Limpopo Valley 1000 years ago (South African Archaeological Society Goodwin Series 8), pp. 14–29; (2000). Shaka was not the inventor of the short stabbing spear nor the horning military tactics which has an older history. The Rozvi (destroyers) can be traced back to the Kalanga that emerged to form the Mapungubwe State, and the successor Butwa state. The term Mfecane (the crushing) is remarkably similar to the meaning of Rozvi.

The Kalanga [48]Schoeman MH & Pikirayi I: Repatriating more than Mapungubwe human remains: Archaeological material culture, a shared future and an artificially divided past; Schoeman, Department of Archaeology, School of Geography, Archaeology and Environmental Studies, University of the Witwatersrand; Pikirayi, Department of Anthropology and Archaeology, University of Pretoria; https://repository.up.ac.za/ / read with – Calabrese J A; Inter-regional interaction in southern Africa: Zhizo and Leopard’s Kopje relations in northern South Africa / read with – Huffman TN; Mapungubwe and Great Zimbabwe: the origin and spread of social complexity in southern Africa. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, 28, 37–54 (2009) / read with – Parsons N; A new history of Southern Africa; pp25-36; McMillan; (1980). started the Great Zimbabwe kingdom, the Butwa kingdom and the Mutapa Kingdom on the historical road to the formation of the Rozvi Empire which indelibly influenced all Southern African social formations. It is a long complex social history which was papered over by colonialism using a vulgar caricature of a mass Bantu invasion of a relatively unpopulated South Africa of the 15th century. All of this progression of African social history, together, is part of the complexity of the peopling of South Africa. Pre-colonial African history was suppressed until fairly recently while the ideologically impregnated empty-land doctrine became the mainstay of schooling and academia.

Evidence shows that the most developed region of Southern Africa was the pre-Mapungubwe Ziwa-Zizho-Kalanga cultures which was a progression of social development between 800 – 1000 CE along the Limpopo River in South Africa. [49]Huffman T; Mapela, Mapungubwe and the origin of States in Southern Africa; The South Africican Archaeological Bulletin; Vol 70 No:201 (June 2015) pp15-27 Evidence also shows that trade between South Africans via intermediaries on the east coast of Africa in Mozambique, had opened up access to Arab, Indian, Southeast Asian and Chinese markets. [50]Huffman TN; Mapungubwe and Great Zimbabwe: the origin and spread of social complexity in southern Africa. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, 28, 37–54; (2009) – read with – Huffman TN; Mapungubwe and the origins of the Zimbabwe culture. In M. Lesley & T.M. Maggs (Eds.), African naissance: The Limpopo Valley 1000 years ago (South African Archaeological Society Goodwin Series 8), pp. 14–29; (2000).

By the time of the multi-ethnic first South African state of Mapungubwe [51]Hall M; Farmers, kings and traders: the peoples of southern Africa, 200–1860. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. (1990) / read with – Ashley N. Coutu AN, Whitelaw G, le Roux P, & Sealy J; Earliest Evidence for the Ivory Trade in Southern Africa: Isotopic and Zoo MS Analysis of Seventh–Tenth Century ad Ivory from KwaZulu-Natal; African Archaeological Review; December 2016, Volume 33, Issue 4, pp 411–435; (2016) / read with – Marilee Wood, Interconnections: Glass Beads and Trade in Southern and Eastern Africa and the Indian Ocean—7th to 16th Centuries AD (Uppsala, Sweden: Uppsala University, 2011). (900 CE – 1100 CE) this trade between early organised South African society and the Indian Ocean and Eastern world, was relatively advanced, and gold, ivory and animal skins from Africa were much wanted products abroad. This was long before the Europeans had found the sea-route to the east and had developed economic relations with much of the world.

The situation changed for the Europeans in the late 15th century, but for the next few centuries this opening up of Asia to Europe was dominated by competitive and conflictual aggression between European powers in Asia. From the latter years of the first millennium trading lines operated in a chain down inland from the west coast and also inland along the east coast all the way to the Western Cape and Cape Peninsula. When Xhore and Autshumao (primarily serving the British) and Isaac (serving the Dutch) had gone abroad they attained global experience. But prior to these events, indigenous South African communities had traded with the outside world through intermediaries at Mozambique ports and Angolans had travelled worldwide in the 16th century.

The beginnings of a new economy and port in Table Bay

Just like the story of the peopling that occurred along the Zambezi and Limpopo, Autshumao and the ‖Ammaqua story alongside the Camissa River in Cape Town is also a story of a social revolution. Van Riebeeck established the reference to Autshumao as ‘strandloper’ simply as a means to convey in the record that no indigenous people lay claim to the Table Bay area, but already by this time other earlier records contradict the journal as will be shown. Effectively Jan van Riebeeck attempted to blot out the social revolution at Table Bay between 1590 – 1652 by disparaging the role of Autshumao, and his general attitude towards the Peninsular Khoi was one in which he likened the Khoi to unintelligent, dirty, savages and beasts. [52]Trotter H M; Vols. 8 & 9: 30-44. Journal of African Travel-Writing Sailors as Scribes Travel discourse and the contextualisation of the Khoikhoi at the Cape 1649-90; (2001);

As one gets more familiar with the van Riebeeck journal, discrepancies arise but also it can be noted that there are plenty of give-away lines about the contestation of the views of the Dutch commander. Van Riebeeck [53]Van Riebeeck J; Precis of the archives of the Cape of Good Hope, Journal of Jan van Riebeeck Part I; pp 37 H.C.V. Leibrandt; p.; Cape Town; W. A. Richards & Sons: (1897). for instances says that:

“Herri in the meanwhile, priding himself on having originated the incipient trade (at Table Bay), proceeds to the Saldanhars, no good expected from it, as he proposes to have as brokerage a copper plate of 1 lb. for every animal bartered – will humour him to find him out.”

This statement is overlooked or downplayed by historians who have constructed a ‘Jan van Riebeeck – founder of Cape Town’ story for which Autshumao’s story presents an inconvenient truth.

Far from being beachcombers, the Watermans or ‖Ammaqua were an entrepreneurial people who valued independence and followed a different economic means of survival outside of the herding or hunting tribe mode, of which they were proud. They were the human manifestation of a social and economic revolution of their times. They were writing a new story in African social history. Through their interactions with many tens of thousands of European visitors over a half century the ‖Ammaqua and Xhore’s people before them, established the proto port character of Table Bay as a refreshment and service support offering in Table Bay.

Over this time, with such huge shipping traffic as will be demonstrated, there also would have been sexual unions from which children of mixed ancestry were also born of travelling African, Asian and European fathers by Khoi women at the Camissa settlement. There is an incorrect assumption that sailor crews were all Europeans, whereas historical record [54]Pereira C; Black Liberators: The Role of Africans & Arabs sailors in the Royal Navy within the Indian Ocean 1841-1941: Geographical Society, London, United Kingdom – Download PDF here – Read with – Ross, Emma George. “The Portuguese in Africa, 1415–1600.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/agex/hd_agex.htm (October 2002) / Read with – Earle T F & Lowe JP edt; Black Africans in Renaissance Europe; Cambridge University Press, (2005). indicate a strong component of more experienced, African, Indian Southeast Asian and Arab seamen. A number of recorded traveller narratives attest to children and people in Table Bay having features considered by Europeans to be Mestizo or Mulatto. [55]Tavernier JB Vol2 p 304. edt V Ball and William Crooke 1925. Travels in India. / Read with Mundy P. edt Sir Richard Carnac Temple Vink M (2003). The World’s oldest trade: Dutch Slavery and slave trade in the Indian Ocean in the 17th Century. Journal of World History Rpr (1967). P 327 The travels of Peter Mundy in Europe and Asia 1698 -1667 / Read with Van Riebeeck J; Precis of the archives of the Cape of Good Hope, Journal of Jan van Riebeeck Part I; pp 137 H.C.V. Leibrandt; Cape Town; W. A. Richards & Sons: (1897). These are the earliest roots of today’s Camissa people – African creole people still labelled by the derogatory colonial and Apartheid term ‘Coloured’.

Elphick [56]Elphick R. Khoikhoi and the founding of White South Africa; pg82; Raven Press. Johannesburg (1985). projects a story that there is record of only 42 shipping accounts from which one can glean the story of engagements between indigenous people and Europeans, whereas more meticulous research [57]Gaastra FS and Bruijn JR (1993). pp 179, 182-183. The Dutch East India Company’s Shipping 1602 – 1795 in a comparative perspective. Ships, sailors and spices: East India Companies and their shipping in the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries. Amsterdam. http://www.vijfeeuwenmigratie.nl/sites/default/files/bronnen/dutcheastindia177-193.pdf of shipping records and travel facts show us over 1071 outward bound ships stopping at the Cape, with around 700 homeward bounds stop-overs. This kind of scant attention to detail and glossing over of facts while over-playing the dominant European narrative results in a skewing of history that simply sees the Khoi in terms of a prelude to “…the Founding of White South Africa” as Elphick’s work is entitled. Elphick also gathers facts from many of the same sources used here but arranges his story differently and comes to erroneous conclusions contradicted by the primary texts. The different lenses that we use to look at the past alter the perspective.

Xhore of the Gorachoqua/Goringhaiqua had been kidnapped by the English in 1613 and taken on board HMS Hector to London and then brought back to the Cape of Good Hope. This had been done on the instruction of Sir Thomas Smythe of the English East India Company. [58]Cope J. (1967) King of the Hottentots, Howard Timmins, Cape Town. Read with Elphick R. pg79. Khoikhoi and the founding of White South Africa. Raven Press. Johannesburg After his return, Xhore was supposed to facilitate the English East India Company’s attempt to establish a colony with ten English convicts from Newgate Prison, under Captains Peyton and Crosse. The colony project failed miserably, but Xhore remained the point-person for the English for a decade. In 1626 he is said to have been murdered by the Dutch after he refused to assist them. It is at the end of this era that the door opened the opportunity for Autshumao’s career as the new point man for the English East India Company. Most South Africans are unware that an indigenous African from South Africa had gone to London as early as 1613.

Xhore of the Gorachoqua/Goringhaiqua was the first known indigenous South African to travel, under force, to London in 1613 on board HMS Hector and was returned to the Cape of Good Hope in 1614. [59]Cope J. (1967) King of the Hottentots, Howard Timmins, Cape Town. Read with Elphick R. pg79. Khoikhoi and the founding of White South Africa; Raven Press; Johannesburg But throughout the previous 120 years many West Africans had travelled to Europe and the Americas and many East Africans had travelled to East Asia. Between 1600 and 1652 the people of Table Bay would certainly have met African and Asian seamen as most European ships crews were experienced Africans and Arabs.

It was alongside a river way down in the south – namely the Camissa River running from Table Mountain to the sea in Table Bay that became a new focal point of a most dramatic coming together of peoples, in the peopling of South Africa during the 17th century and beyond. The motive forces that led to this new chapter in the peopling of South Africa was the expansion of European trade and influence in Asia, whereby the Cape of Good Hope and its people provided a much needed re-provisioning service as a halfway refreshment station for international shipping. By far the most important personality of this time is our subject, Autshumao of the ‖Ammaqua whose career began when he journeyed from the Cape of Good Hope to Banten (Bantam) in Java. [60]Elphick R; Khoikhoi and the founding of White South Africa; pg 79 Raven Press. Johannesburg (1985).

Autshumao and the Java experience

By mid-1500 the Arab world had also extended imperial and Islamic influence eastwards to India and Southeast Asia which clashed with European trade expansion, colonisation and Christian proselytization activity in the east. According to Barbara Andaya and Leonard Andaya [61]Andaya BW & Andaya LY; pg134; A history of early modern Southeast Asia 1400-1830. Cambridge University Press.(2015). (pg 134) in 1494 the great Catholic powers – Portugal and Spain, through the Treaty of Tordesillas agreed to a division of the world beyond Europe. Under Papal Patronage the two crowns undertook to spread the Catholic faith in newly discovered lands. Java and Makassar in Sulawesi became one of the centres of the clash of Christianity and Islam when the Portuguese first made its presence felt in 1522.

The Portuguese, however, did not make much headway because by the end of the 16th century the Arab Muslim influence had a firm foothold and Portuguese stature as the dominant European power in the east was on the decrease. In 1596 the Dutch first asserted themselves in Indonesia and were to dominate until the end of the mid-18th century when the English became the rising imperial power.

By the early 1600s the Dutch were way ahead of the English. Nonetheless the English East India Company was rapidly increasing as an economic threat to the Dutch. Barbara and Leonard Andaya [62]Andaya BW & Andaya LY; pg202-206; A history of early modern Southeast Asia 1400-1830. Cambridge University Press (2015). tell us that by 1603 the English had a strong presence and factory in Banten (Bantam) in Java which they operated until the Dutch evicted them in 1682. Banten (Bantam) in West Java was an international centre of trade under Sultan Ageng Tirtayasa. The Dutch plotted together with the Sultan’s son who took over from his father by military means by using the VoC troops from Batavia (Jakarta) to secure victory and this calculated act led to the expulsion of other Europeans, especially the English. The religious leader who had opposed the Dutch expansion in the region – the charismatic Muslim intellectual Sheikh Yusuf of Makassar [63]Mansoor J: Guide to the Kramats of the Western Cape; pp 17 -19; Cape Mazaar Society; Cape Town (1996). – was forcibly exiled to the Cape Colony in 1683 where he remain for the rest of his life and became the founding father for the Islamic faith in South Africa.

It was to this British port at Banten (Bantam) in 1630 that the English took Autshumao as an intern to become their agent at the Cape of Good Hope. It is here that Autshumao would learn about European rivalry, strengths and weakness. He further learnt the value of getting to know the different languages of these powers in this international centre of trade, because all of them – English, Dutch, Portuguese, French and Danish had to stop over at the Cape of Good Hope.

Autshumao would have encountered those called Black Portuguese [64]Andaya BW & Andaya LY. (2015) A history of early modern Southeast Asia 1400-1830. Cambridge University Press. , known as Topasses or Mardijkers, who were the offspring of Portuguese men and East Asians. He would also have encountered African and Southeast Asian slaves who are likely to have left a great impression on him as a person regarded as a Free Black in the East and would have made him value his freedom. He further would have come to appreciate how important the Cape of Good Hope was as a halfway refreshment station to European trade in spices, silk and slaves. This would further have enlightened him as to the value that could be placed on local required commodities from the Cape. Indeed from 1615 the Cape was a compulsory maritime stop-over port. In understanding all of this, Autshumao would clearly have seen opportunities as well as threats and, this period of education and training would serve Autshumao very well when he returned to the Cape to establish the first indigene run proto-port operation. Much later when the VOC commander Jan van Riebeeck bullied him out of the port operations, van Riebeeck himself notes in his journal that Herri challenged the Dutch Commander’s usurping of his project. [65] Van Riebeeck J; Precis of the archives of the Cape of Good Hope, Journal of Jan van Riebeeck Part I; pp 37 H.C.V. Leibrandt; p.; Cape Town; W. A. Richards & Sons: (1897).

Given all of this background it should be apparent that the disparaging remarks about Autshumao being an ignorant and crooked, dirty good-for-nothing beach scavenger when engaging with van Riebeeck and his VOC party at the Cape from 1652, is nothing but crude colonial distortion. So what then is the story of Autshumao?

Autshumao – agent of the English, entrepreneur and Governor at the Cape

It can be deduced that Autshumao was born around 1605 – 1610 and as a child grew up with the Gorachouqua/Goringhaiqua people who had pioneered the earliest trading relationships with European ships under Xhore. Around the age of 20 – 25 years Autshumao agreed to accompany the English to their factory in Banten (Bantam) in Java [66]Elphick R; Khoikhoi and the founding of White South Africa; pg 79 Raven Press. Johannesburg (1985). where he learnt much from them and also about the other Europeans.

This opportunity had come his way having been prompted by favourable experiences that the English had when stopping over at the Cape since their early trips in 1602. In 1613, Aldworth [67] Best Thomas. Edt Foster William (1934). 251 The Voyage of Thomas Best to the East Indies, 1612-1614 – Letter of Aldworth Thomas at Surat 1613 to Sir Thomas Smythe. Asian educational Services. Delhi , a champion for English Settlement at the Cape who was President and Factor of the English Factory in Surat, stated in a letter to the English East India Company in relation to the Cape of Good Hope:

“… the climate is very healthy, insomuch that when we arrived there with many of our people sick, they all regained their health and strength within twenty days”. Furthermore, the letter states, “… we found the natives of the country to be very courteous and tractable folk, and they did not give us the least annoyance during the time we were there.”

In the period 1610 to 1620, English ships stopping at Table Bay increased by ten times the number of the previous decade which impressed upon the English East India Company that they needed to have a trustworthy agent at the Cape of Good Hope to serve shipping needs.

There are many different reports from the beginning of the 17th century that paint the picture of European engagement with the Cape Khoi people. Theal [68]Theal G M (1887). Pp 25-26. History of South Africa 1486-1691. Swan Sonnenschein & Co. London tells us of Joris Spilbergen, commander of the Dutch fleet, who gave Table Bay its name on a visit in 1601. He mentions sick sailors being conveyed to land where a hospital was established. Raven-Hart [69]Raven-Hart R.1967. pp23-40 Before van Riebeeck: Callers at South Africa from 1488 to 1652. Cape Town: Struik provides the figures of 1 839 sheep and 149 cattle being traded to four ships between 1601 and 1608. Tavernier [70]Tavernier JB. p 205. The Six Travels of Jean Baptista Tavernier. trans. J. P. (London: R. L. and M. P. 1678). reports:

“So soon as the ship arrives, they [the Cape Khoi] bring their beasts to the shore with what other commodities they have, to barter….”.