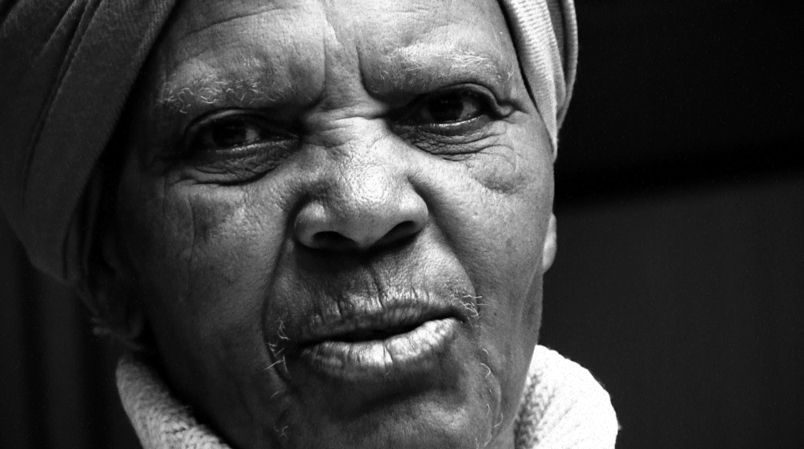

NEO MUYANGA

A Memory of Us - the songs of Mantombi Matotiyana

Inkumbulo Yethu Sonke - amaculo kaMantombi Matotiyana

‘Memory is what makes us who we are’ -Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o

Inkumbulo ngiyona into esenza sibeyithi uqobo’ -Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o

I’d like to begin this discussion on the topic of the music of indigenous tradition, particularly the music of Mantombi Matotiyana, by reminding the reader that this is, in fact, hardly the kind of music we can expect to see dominating the airwaves on television or radio in South Africa. Indeed this is music that is also not widely taught at local universities, where the main thrust of studies in music is weighted either towards elevating the study of the music of European composers who lived as long ago as the 19th century (what is generally termed classical music) or the music of composers writing in the tradition of Jazz during the 20th century – these are the two kinds of music we have been taught to value and consider worthy of academic analysis. The music of indigenous tradition is by contrast generally not regarded as available for, nor indeed requiring, deep analysis.

Ngizoqala ukukukhulumisa ngaloludaba lomculo wasekhaya, kakhulu owaka mam’Mantombi Matotiyana. Ukukukhumbuza, akuvamisanga ukuvezwa kumabonakude noma emsakazweni lapha emzansi. Futhi lomculo awufundiswa kakhulu njengezinye izifundo ezijwayelekile emanyuvesi, lapho sifundiswa khona. Lapho, sifundiswa kakhulu ngomculo wabaqambi ababephila e-Europha ngeminyaka ya kudala ngo1800’s (obizwa ngokuthi ungowe-Classical), noma umculo owabaqambi abavela eMelika ngo1900’s ebizwa i-Jazz.Yilowo ke umculo esafundiswa ukuthi yiwona umculo ovamisa ukufundelwa ezingeni eliphakeme. Umculo owasemakhaya wona uvamise ukubukeka njengo mculo ozifundelwa nje ngokwakho, umuntu uma ethanda. Futhi awuvamisanga ukubhekisizwa njengo msebenzi o dinga ukuhlaziywa.

According to music pedagogue Yolisa Nompula, the state of affairs concerning indigenous music education is as dire now, in post apartheid South Africa, as it ever was. She argues,

Wayeshilo umfundi wezomculo, uYolisa Nompula, esebalabalisa ngesimo sezifundo zomculo eMzansi Africa mas’ethi nanamuhla, lapho umhlaba usukhululekile ngemva kwe-apartheid,

‘There is very little or no availability of African music

material in the curriculum. In music and arts education

there are still strong voices that stereotype indigenous

knowledge as backward and proletarian’ (Nompula 2011, p1-2).

This is what ensures the continuance of the status quo wherein the acquisition of such indigenous music is only possible to learn while kneeling at the instructive feet of our elders, the grandmothers and grandfathers who still possess such knowledge. Where imbibing this oral tradition from the elders is not possible, however, – in the case that is where even the elders aren’t knowledgable of the practices of old – we as contemporary musicians working before our audiences at concerts or music festivals must take the initiative to learn this form of music by ourselves. In order to take such initiative a musicians must already possess a love or fascination with it. One of the fundamentally important ways to evolve such a love and fascination for this music proceeds from listening to and appreciating this music when it is performed by experts such as Mantombi Matotiyana.

Cha! Lomculo owesintu ungumculo omele siwufundiswe emakhaya wethu, ngabo oGogo naboMkhulu bethu. Ku ngejalo – uma noma uGogo engazi naye, loko kusho ukuthi kumele sizifundele wona thina, nje ngabenzi bomculo abadlala phambi kwabalandeli emakonsathini nakuma-festival o’mculo. Se ngisho konke lokho ukukukhumbuza ukuthi umuntu ukuze ewuthande lomculo, kumele lothando lukhuliswe. Thina sikhulisa lothando ngokulalela nokumamela oGogo abafana nje ngoMantombi Matotiyana

To develop a general love and appreciation for this music within the public sphere today demands the exertion of effort by individuals and specialist music societies who will work to recover, to restore this music as a living memory in today’s society. These will be individuals and entities such as those at the Africa Open Institute who have been instrumental in supporting this new release by Matotiyana. Why do i believe this?

Ukuze uthando lukhule lomculo o nje ngowaka mam’uMantombi kubantu jikelele, kumele uvuk-uzenzele awusebenzele, azakhele inkumbulo yawo. Lowo msebenzi kumele uyenzwe yimbumba nemiphakathi yezomculo njengeAfrica Open Institute. Labo kuyibona abasize ukulungiselela yona lerekhodi ka mama uMantombi entsha. Kungani ngikusho lokho?

It is because, as Ngũgĩ reminds us that,

Lokhu kungoba njenga esho mayeqhubeka u Ngũgĩ athi,

“What the colonial process does, or any process of domination

(does) is first of all the erasure of the memory of the subjugated.

You literally erase the memory of who they are; the memory of the past”.

“Okwenziwayo ngiyinqubo yobukolonisi iwuku susa

imkumbulo eyaka lowo muntu e’mqindezeleyo

ukusisa kwenkumbulo yokuthi ungubani futhi

nenkumbulo ya konke okusedlule.”

According to Ngũgĩ it is just such an act of erasure that makes it appear as though the memory of the oppressed begins with the arrival of the colonists and their mechanisms and modalities for effecting hegemony.

Uthi uNgũgĩ leyo ntsuso ‘yenkumbolo iyenza abantu abaqindezelwe babone ungathi inkumbulo eyabo iqala ngokufika kwamakolonisi futhi nokuqindezelwa kwababo.

Furthermore, this erasure is one of the acts of cruelty which may be said historically to have resulted in the festering of what Walter Mignolo has termed ‘the colonial wound’ (Mignolo 2011). Addressing this wound is, I believe, precisely where the release of Mantombi Matotiyana’s new record, entitled ‘Songs of Greeting, Healing and Heritage’ proves invaluable – however, in order to develop a love and appreciation, as well as a memory, of this indigenous music, we require the embodied memories of elders who will pass down this form of music and with it its cultural traditions and knowledge systems.

Ukudlula lapho, leso senzo sobudlova esokususa inkumbulo yabantu iyona into eyazala lokho uWalter Mignolo akubiza ngokuthi kuyisilonda sobukoloni (Colonial wound) (Mignolo 2011). Yilapho ngikholwa ukukitshwa kwerekhodi elisha laka Mantombi Matotiyana elibizwa ngokuthi, “Songs of Greeting, Healing and Heritage” [Ingoma Zokubulisa, zeMpiliso neSintu] lisizela khona nqo! Kodwa ke ukuze siwuthande lomculo owesintu, kudingeka inkumbulo zaboGogo abazoyifundisa lendlela yokudlala, futhi ne yokufundisa amasiko wethu womculo.

It has already been for many decades that Mantombi Matotiyana – who is now 86 years of age – has consistently done the work of disseminating such knowledge. Yet this is the first-ever opportunity for her to release a recording of her own. On it she regales us with old favourites such an “Wen’ useGoli”; “uMajola” and “Embo” (this latter a song that deserves special mention here as her solo voice sparkles with particular nuance, strength and beauty).

Kusekudala ewenza lomsebenzi wakhe umama uMantombi, nje ngoba eseneminyaga ewu-86. Kodwa ke – yi lona ithuba lakhe lokuqala ukukhipha irekhodi eliphelele e libiza yena nqo! Kulo, udlala amaculo asiwaziyo namanye athandwa ngithi kakhulu, nje ngo “Wen’ useGoli”; “uMajola”, no “Embo” (kulapho kulengoma yokugcina ekubonakalisa ubuhle, amandla, nolwazi obukhona ezwini lakhe umama uMantombi).

As already pointed out, restoring and developing the memory of indigenous music is one of the modalities we might call upon to assist us in ‘decolonizing the mind’ (Ngũgĩ, 1986). That is because reviving memories of this indigenous music does indeed remind us of who we are. However this also raises a question about why it is that experts such as umama uMantombi Matotiyana continually consult the same strict repertoire of indigenous songs as old (and as venerable) as they are?

Njengoba besesishilo, ukukhulisa inkubolo ya lawo maculo wesintu ingenye indlela yokuzisiza nayokuzikhulula amaketanga awobukolonisi enqondweni yethu (Ngũgĩ, 1986). Lokhu kungoba lawo manculo asikhumbuza ukuthi singabobani thina. Kodwa ke lokhu kungenza ngifune ukubuza ukuba kungani oGogo bethu abasebenza ngezingoma zesintu, njengaye umama uMantombi, behlala bephindisa amaculo akudala, asemadala njengabo?

To be sure, this is a repertoire that is much beloved and respected, but why does it remain a first port of call for elders whose everyday lived experience currently is vastly different from the past in which the material would have first been conceived and played – after all these are, in many cases, experts who’ve completely assimilated into urban life, and whose musical creations are also subject to the exigencies of contemporary economics as part of a record industry that is in every meaningful sense a globalised business concern – how then do we interpret the fact that on her latest record umama uMantombi sings, ‘Masiye Embo’ [‘Let us go back to the land of origin’]?

Yebo, sishilo sathi sisawathanda lamaculo, kodwa kungani bona impilo yabo oGogo, noma isishintsile. Njengabasaphila emadolibheni, lapho umculo wabo nawo use uyinto e buswa ngimithetho eyomnotho, ngoba phela amarekhodi wona athengiswa ngosomabizinisi abakhulu mhlaba jikelele. Manje ke kungani umama uMantombi, nabanye abadlali bomculo owesintu, bacula ingoma ethi, ‘Masiye Embo’?

Does umama uMantombi really imagine we can take ourselves back to our origins? No, I do not believe that is in fact the case. This is in part of course due the changes which have taken hold of the songs themselves inevitably, due to the context in which they are performed and captured today, as well as the modes by which they are disseminated to serve the purposes of the market as well as other considerations. Therefore, they’ve become transformed into a set of very complex arrangements that are capable of existing as bridges linking multiple realities.

Ingaba umam uMantombi ucela sizibuyisele emva? Qha, angikukholwa lokho. Kodwa mina ngithi noma kungelula ukubona, indaba-nkulu yikuthi lawo maculo nawo kade waphenduka, eyenzwa ngumongo osuhlukile olungele imishini yokurekhoda neyokuthengiswa, noma wona mculo usenza umsindo ofana nowakudala – amaculo lawo asephendukhe waphila izimpilo eziningi ngomzuzu owedwa kuphela!

How is such a thing as this possible? It is precisely because what keeps these indigenous songs vibrant is an able musician’s memory of a musical past. What gives them a seemingly eternal life is an orally-transmitted imagination of a future that is viewed as hurtling through time to come and meet the present.

Njani? Ingoba lawo maculo aphiliswa ngekumbulo yezendlule emqondweni nasezandleni zomdlali womculo. Futhi aphiliswa kunaphakade ngomcabango wekamva elizayo ukuzohlangabeza ngesikhathi samanje.

To better understand the multi-dimensional nature of this repertoire of songs then, we might refer to them under the rubric of the Ghanaian concept of Sankofa, which Daniel Appiah-Adjei explains, ‘Sankofa is an akan word that means “we must go back and reclaim our past so we can move forward; so we understand why and how we came to be who we are today” (Appiah-Adjei 2016, p 2).

Ukulizwisisa kahle loludaba lempilo lezinstuku-ziningi ngomzuzu omunye kumele sibhuke kumcabango obizwa ngokuthi Sankofa, ovela e-Ghana: uma awuchaza u-Appiah-Adjei uthi, ‘iSankofa kuyigama elesi-Akan, elikhuluma ngokuthi kumele sibuyele siyofunda ezedlule ukuze sikwazi ukufinyela ikamva lethu.” (Appiah-Adjei 2016, p. 2)

This active bridging of a past and a future, then, is what I perceive as the work being carried out in the present by umama uMantombi when she sings,

Yiyo ke into mina engiyibona iyenziwa ngumama uMantombi uma ecula ethi,

‘Wen’ useGoli, uzaw’ fuman’ into ezibandayo

apho.. iyo haa! Iphelile madoda’

‘You who are in the place of gold,

that is where you will find only coldness.

hat’ll be the end of it’.

What this song reminds us of very starkly is that, historically, the homelives of millions black people in this country were dismantled through the imposition of law as under the colonial regime of the Cape, and the ravages continued to mount as apartheid became institutionalised, turning largely self-sufficient denizens into workers and then into prisoners of an extractive, exploitative and racialised economy of gold and diamonds, far away from their origins. Their original lands were later designated as ‘homelands’, strategically dispossessing them of their South African nationality. The displaced masses subsequently desperately needed to secure or retain the work in the urban periphery as for many that became the only way to financially sustain their impoverished families back home: a self-perpetuating cycle of misery.

Is this not indeed the ‘coldness’ referred to so saliently in the song?

Ingoba leliculo lisikhumbuza udaba lokuthi izimpilo zabantu abamnyama emakhaya kade zaphihlizwa ngemithetho eyavela mhla yobukoloni eKapa, yaze ya qhubekiswa ngemihla yo mthetho we-apartheid. i-Apartheid iphendula abantu ababekwazi ukuziphilisa ngokulima wabenza abasebenzi. Emveni kwaloko yabenza iziboshwa zomnotho wezimayini zegolide ne zedaimani, ya basusa emakhaya wabo, lawo bewebizwa ngokuthi ngamahomelands’, ya bazisa emadolobheni a nje ngeGoli, ukuze batholeimisebenzi lapho. Imisebenzi yase dolibheni beyidingega ukuze bakhone ukuphilisa imndeni yabo emakhaya abeshiyeke e gxeka nge nxa yenhlupheko eyazalwa ngengcindezelelo yawo umthetho we-apartheid: umbuthano ozenzayo abuye ezidle ngokwakhe! Yizoke ngempela ‘into ezibandayo’ lezo.

When we delve even deeper to listen to the music accompanying ‘Wen’ useGoli’, for instance, we can hear in the transparent clarity of the present recording the overtone series that rings out of the scraped Mrube, rounded out by the wistful whistle intoned by the player. The ensemble sound heightens our awareness of this as the ancient music of fourths and fifths of this region.

Masiqhubeka silalela umculo ohambelana nengoma, ‘Wen’ useGoli’, sizwa umculo wesiko odlalwa ngoMrube lapho sizwa ama-overtone egcwaliselwa ngumdlali eshaya ikhwelo. Loko kuveza umsindo omnandi owesintu okhala ngolwimi olwe-zine (fourths) ne zinhlano (fifths).

Though it may seem like something of a digression here to describe umama uMantombi’s ‘origins’ music as consisting of fourths and fifths, it becomes imperative to mention here the extent to which contemporary discourse in the field of comparative musicology is finally showing a preparedness to sustain highly reflexive debate concerning the provenance of such key concepts within musical analysis. Clearly, the identities of the musical proportions of the fourth and fifth in a musical series weren’t actually a western or European invention. However the claim of being unique in deploying certain concepts in musical analysis served a strategic purpose for a materially avaricious Europe. According to David Irving,

Lana ngiyethemba bazobakhona labo abazo mangala manje, bathi ngisebenzisa umcabango wesilungu mangi khulumisana ngomculo we sintu kodwa ngiwubiza umsindo ‘owezine ne zinhlanu’. Futhi ngizobaphendula ke labobantu ngokubabonisa ukuthi kuzekwaba umcabango o amukelekile lona kwimifundo zemfanisano lwezomculo (comparative musicology) othi umsindo owezine nezinhlanu awuqalangwa ngabelungu, noma abeseYuropha (European). Kusho uDavid Irving athi,

‘Increased European engagement with the world from the 16th

to the 18th centuries had a profound impact on musical

taxonomies, a major legacy of which is the artificial

dichotomy of “Western music” and “World music” –

as well as the attendant distinctions between academic

disciplines that focus on these fields – mediated by

a discourse of modernity’ (Irving 2018, p 21-22).

‘Ukubandakanya phakathi kwe-Europha nomhlaba-jikelele

kusika kwiminyaga yezi-1500’s kufikela kwizi-1700’s

kwayenza ukuthi indlela leyosikhulimisa ngayo kwezomculo

kufakwe inhlukaniso ekungeyona eyemvelo phakathi

kwomculo owaseYorupoha na lowo oyenziwa kweminye

imihlaba yasezweni ukuze kubenesethulo somcabango

wesimanje-manje’. (Irving 2018, p 21-22).

Irving argues that such strategies were instigated in order to invent the bigger concept of European exceptionalism as the nations of that continent vied to usurp control of the whole world.

Ukuya ngoIrving, loko kwayenzwa ukuze kuqanjwe umcabango owobukhoni obungejwayelekile ngabantu base-Europha (European exceptionalism). Loko kwayenzwa ngoba amazwe ase-Europha bewefuna ukuzibonisela kwiyiwo kuphela aphethe amandla wokubusa wonke umhlaba.

The inevitable outcome of the deployment of such powerfully destructive strategies across an entire globe are some of the reasons why to the present day a noticeable absence of a commensurate language persists for making musical analysis in indigenous languages. In a country like South Africa today we pay lip service to transformation and redressing the disparities within the academy. Yet while on the one hand there is a professed desire to elevate the indigenous arts, there is also on the other hand much a disconcerting continuity with our unequal past, leaving pedagogic specialists such a Nompula troubled at the state of play in the arts curriculum.

Lowo msebenzi owayenzwa ukuze i-Europha inqobe kwaba empeleni impihlizo enkulu eyezwe. Namuhla kuyabonakala ukuthi amagama esiwasebenzisayo awokuhlaziya umculo wethu awenele neze. Ezweni elinjenge Mzansi Afrika, lapho sithi sizimisele ukupucula isimo sezimfundo zomculo wesintu, kodwa simane siqhubekisa isimo ebesitholakala ngemihla ye-apartheid ezindabeni zemfundo yomculo wesintu. Njengobeseshilo uNompula ukuthi loko kuyakhathaza kakhulu.

In what way could we envision effecting a change in the current status quo? I believe that in no small part, the release of Mantombi Matotiyana’s record may serve as instructive:

Silinqoba kanjani ke loludaba? Ngiyakholwa mina ukuthi lelirekhodi likaMantombi Matotiyana lizokwenza ithemba ngendlela ezimbalwa ezibalulekile:

mamaMantombi models a way of embodying a memory of our past, even while she lives an urban existence. She reminds us how she herself has had the opportunity to tour and to see the world, even while she is living a local existence, attached as she is to her music and its old ways.

She embodies the spirit of Sankofa by going back to her origins to collect a knowledge that continues to glisten there within the dimension of memory and she succeeds in bringing that across space and time to encounter an imagined future where people begin to remember how to fetch their own memory.

Umama uMantombi uzibonisa eyinkumbulo yomculo wesintu, noma yena ephila impilo yasemadolibheni. Ushilo naye wathi useke wawubona umhlaba, kodwa usayiphila yona impilo yasemakhaya, ngenxa yomculo awuculayo, uphila ezintsukwini eziningi ngomzuzu owodwa. Usibonisa indlela nathi esingafuza isiboniso nawo umzekelo owenyoni, uSankofa – siphande ulwazi kwezedlule, siluzise luzokhanyisela ikamva lethu.

Further to this, Matotiyana models for us what Ngũgĩ calls ‘planting’ or inserting a memory of our past into the present, for the purposes of determining different futures for ourselves to the unidimensional one assured us by the hegemony of our former oppressors and to avoid the traps of any that may be lurking ahead of us.

Ngaphezulu kwaloko, umama uMatotiyana uyenza kube sobala ukuthi singaziphandela kanjani izinkumbulo ezokwedlule, sizitshale okwamanje ukuze sikwazi ukwakha ikamva oluningi, oluhlukile kwikamva-linye esalibekelwa ngabacindezeli bethu abadlulile, futhi okungasisiza ukugwema nabaye mhlawumbe a bangaphambili kwethu.

Bibliography

Amanothi

Appiah-Adjei, D. (2016) Sankofa As A Universal Theory For Dramatists [Unpublished Paper] 21/1/16Available at https://www.researchgate.net/ [Accessed 3/6/19]

Irving, D.R.M (2018) Ancient Greeks, World Music and Early Modern Constructions of Western European Identity, Strohm, R. ed. (2018) Studies on a Global History of Music: Routledge, pp 21-41

Mignolo, W. (2011) The Darker Side of Western Modernity – Global Futures. Decolonial Options: Duke University Press

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o (2015) Memories of Who We Are, Louisiana Channel [Video Interview] 13/10/2015

Available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AYP9sJvDcYE https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AYP9sJvDcYE [Accessed 21/5/2018].

Syms, M. (2013) The Mundane Afrofuturist Manifesto, Rhizome [Blog] 17/12/13 Available at http://Rhizome.org [Accessed 18/3/18].