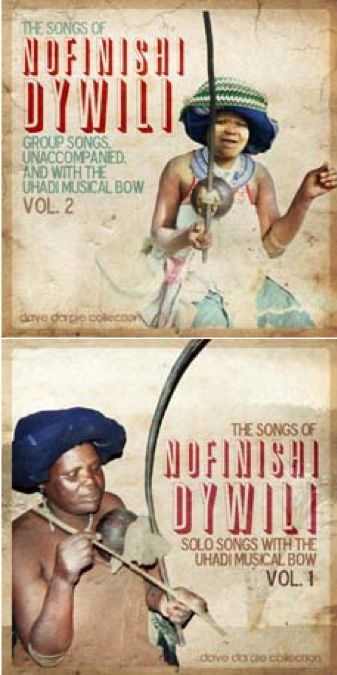

In 1998 I was present at a concert in Grahamstown, as it was then (now Makhanda), at which I heard the legendary Nofinishi Dywili and the Ngqoko overtone singers giving a concert of traditional Xhosa music. The local eurocentric music society had admirably decided to branch out and give indigenous music a chance, but sadly there was an audience of about 20 in a 1000-seater auditorium. I was transfixed by this music, at once earthy, the deep voices and clapping of the women – and ethereal – the overtones of the voices and the instruments (uhadi and umrhubhe). That was my introduction to music which up to then I knew little about, but which has since become integral to my compositional aesthetic.

In 2000 I started a festival in the Eastern Cape, the ‘New Music Indaba’, as a platform for NewMusicSA, the newly-established South African section of the International Society for Contemporary Music. Each festival boasted a project which involved the commissioning of new pieces from South African composers, and in 2002 I and my co-director Grant Olwage had the idea of inviting composers to transcribe, arrange and reimagine a song by Nofinishi Dywili.

The arrangements and reimaginings would involve a Western bowed ensemble, the string quartet. The pilot project in 2002 involved just two composers, Andile Khumalo and Martin Scherzinger, but such was its success that in 2003 we commissioned another eight composers and from then on ‘The Bow Project’[1]https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Bow_Project as it was known, became a regular highlight of the New Music Indaba until its demise, at the National Arts Festival, in 2006.

Mantombi Matotiyana is one of two great Pondo musicians – the other was Madosini – who took part in these performances. I was introduced to her by a fellow composer Hans Huyssen who had previously worked with her. As a means to bridge traditional and new musics, Mantombi – or Madosini – presented Nofinishi Dywili’s songs as a prelude to each new string quartet composition.

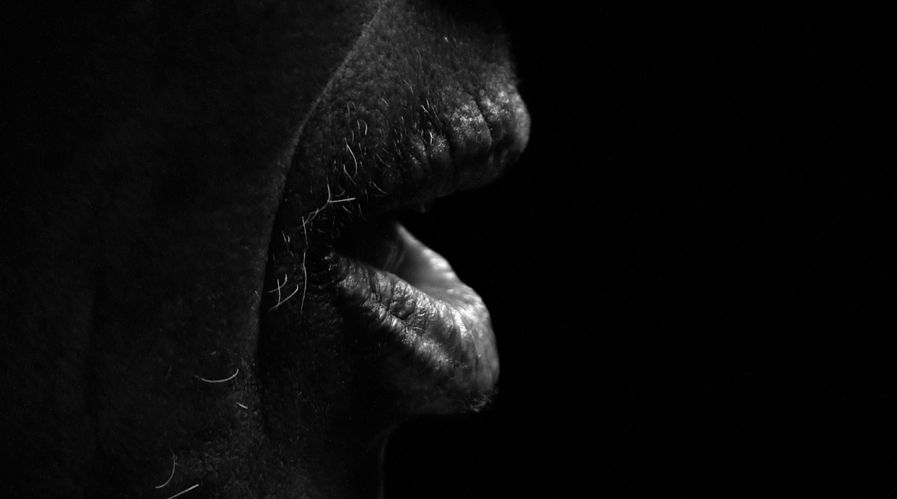

They also performed their own music in concert during the New Music Indaba and always played to packed houses. Apart from her deep, rich voice which almost moves the earth beneath one, I also became aware of Mantombi’s extremely fine, virtuoso playing of the umrhubhe, the friction mouthbow.

On that instrument she would perform many of the same songs that she sang with uhadi accompaniment, which put me in mind of Western instrumental transcriptions of songs, for example Liszt’s transcriptions of Schubert’s songs or for that matter, instrumental covers of many fine popular songs of the 20th-century. Of course the texts of her songs – most songs – are very important for the meaning, but I think it true to say that Mantombi conveys feelings and emotions as keenly or intrinsically as any opera aria for example. The words help to articulate the music, the music articulates the emotions.

Sometime in the future I knew that I wanted to create an original work with and for Mantombi. But first we were responsible for the continuation and completion of The Bow Project, and Mantombi and I collaborated again on the Bow Project Tour in 2009, giving concerts on six university campuses around the country. For Mantombi, who has suffered with a leg injury for many years, travelling in a minibus around the country with some very long stretches, it was a particularly grueling tour. But she never complained and always maintained her gracious composure, and her willing and professional attitude.

Nishlyn Ramanna wrote of the concert in Durban: “The Bow Project addresses music’s capacity to bridge the chasms that seem to separate modern and traditional, spiritual and secular, or Western and African/Asian cultural spaces”. Mantombi’s performances made an indelible contribution to bridging that chasm, but she always reminded me that these were not her songs, they were Nofinishi’s songs.

Then in 2013, I was commissioned by the Festival d’Automne à Paris to compose a new work and was at last able to realise my long-held wish to make a piece for electronic tape and live umrhubhe, featuring Mantombi as soloist. Over a period of six months we worked regularly in the recording studio at the Stellenbosch Conservatoire of Music, creating material for the electronic tape. We spent another month rehearsing the completed work, Ukhukhalisa Umrhubhe (meaning “to play the umrhubhe” or literally “to make the umrhubhe cry”), and took it to France for two performances, and it was subsequently broadcast on France Musique.

I realized even before I started that I could not present Mantombi with a traditional staff-notated score or a graphic score, and had the idea to make a series of recorded “models” from which she could create a solo part for the umrhubhe. But actually the solution was an improvising role for her based on the music of the tradition in which she works, so that in the end this was very much a collaborative work.

I also recorded her voice in the studio with a pre-recorded vocal and uhadi accompaniment on headphones and incorporated some of those recordings into the tape part (other elements are midi keyboard and percussion tracks, and processed uhadi and umrhubhe). Playing these voice takes in the car when I drove her back home after the sessions, I was thrilled to hear her add a beautiful but discreet harmonization as we headed back along the N2.

During the course of our collaboration, especially when people encountered Mantombi carrying her uhadi in airports in South Africa, they often asked us where they could find her CDs. She had never recorded a solo album, and this prompted me to initiate the recording and release of ‘Mantombi Matotiyana: Songs of Greeting, Healing and Heritage’. Africa Open Institute sourced the funding and thanks to Stephanus Muller, the album was recorded on the weekend of 15/16 July 2017 and released in 2019.

Mantombi was no stranger to the recording studio when we first started working together, in fact so experienced was she that our colleague Ncebakazi Mnukwana had coined the marvellous title “queen of the one-take”. Her recordings needed little editing, but on the solo CD she took the opportunity to do overdubs giving us the pleasure of having many Mantombis at once. What was also new to me was hearing her play the isitolotolo (Jew’s harp) in two of the tracks. But it made sense because this instrument produces overtones just like the bows. For me she elevated this humble little instrument, used mostly in folk and popular music and occasionally by classical composers – Vivaldi in a concerto and Charles Ives in one of his orchestral works – into a virtuosic, mesmerizing medium.

My whole experience of working with Mantombi, since 2003, has been coloured by the fact that I have very little isiXhosa and she has almost no English. Every project has required an interlocutor to convey concepts and plans, but surprisingly this has not been a source of frustration for either of us, and perhaps has led to a greater desire to experiment. And Mantombi has always been keen to try whatever I have proposed; sometimes we failed, mostly we were happy with the results.

Visiting her at her modest home in Philippi on the Cape Flats was always a humbling experience. She lives very simply and though her great friend Dizu Plaatjies talks of renovating her tiny house where she lives with her extended family when she is in Cape Town, she is quite happy with things as they are. She is a proud woman and completely sure of who she is. Nowadays she lives back in the Eastern Cape, but returns to Cape Town from time to time, most notably for the magnificent launch of her CD in April 2019. It was a wonderful reunion for us after a break of several years since we collaborated on Ukhukhalise Umrhubhe. We were both delighted to see each other and I was excited about hearing her perform live. She was still totally in command and dominated the evening with that wholly recognisable voice of hers.

Photos and videos by Aryan Kaganof.