MARIETJIE PAUW

Life writing 7 Joubert Street: a memorialisation

In this article I explain why I set about researching the address 7 Joubert Street, Stellenbosch. I indicate where I found some clues by what I call the ‘luck’ that grows out of being with people. I write about the address, about its urban and ideological history, and point to some of the names and some of the connections between the people who called 7 Joubert Street their home. I write to remember a time before the ‘first’ family re-located to Ida’s Valley, a neighbourhood to the north-east of Joubert Street. In the course of life writing 7 Joubert Street I also write-play, as musician – with artist colleagues – into the many things we still do not know. We write and play to create a memorialisation of a family who navigated socio-political trauma.

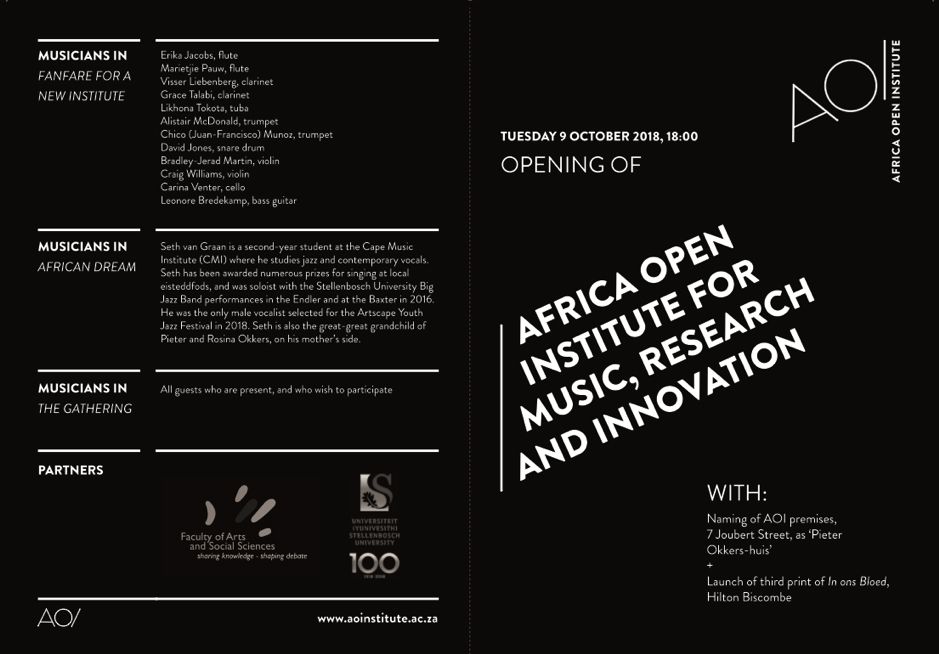

After the establishment of the Africa Open Institute for Music, Research and Innovation (where I am a researcher) was approved by the Stellenbosch University Council on 11 June 2016, it took approximately a year and a half before the University of Stellenbosch allocated the Institute rental premises where research and curations could take place. In October 2017 the institute moved into a property of the University of Stellenbosch on 7 Joubert Street. The Institute wanted to celebrate the new premises with an inauguration and a possible naming of the house, but could not do so without knowing more about the history of the plot, the built structure, the area, and possible connections to and between the previous occupants.

The research has enabled connections between the institute and its historical and geographical landscape. The article is also an enmeshing of my practice as a flutist with colleague musician Garth Erasmus, and an engagement with filmmakers, Hilton Biscombe and Aryan Kaganof, whose artworks animate the writing. The research-praxis that we engage in, proposes the capacity for historical, and curatorial intervention: to re-tell the narratives of this place, and thereby re-open wounds that are all too easily glossed over. The article is a bringing-together of life writing as an ‘anthology of existences’ (Foucault 1979). In using various registers of formality, this article is a creation of assemblages of art, research and human connections.

Wall Imprints

On 20 June 2018, my daughter, Hildegard Conradie, and I, imprinted copies of documents onto the interior walls of 7 Joubert Street, Stellenbosch. We used a data projector to screen the surveyor general drawing of 1903, the first house plans of 1927, as well as the deeds transferral of 1951 whereon Erf 2453 was officially ‘stamped’ by apartheid. We projected photographs of persons (who had perhaps lived in the house) onto the walls, including Pieter and Rosina Okkers with four of their granddaughters, as well as Rosina (Sinnie) Gordon as a young adult. We screened former researchers who had worked in the building—‘nuclear’ physicists,—next to the fire extinguisher.

The photographs that we projected onto the walls displayed icons from my laptop, including ‘Google’ and ‘Windows’ images. The pervasive presence of these tabs remind us of the disjuncture between reality and our art projections: The icons prompt the notion that we were dabbling in unreality: We were creating an imagined collage of Piet Okkers and Sinnie Gordon who could never return to our premises in fleshed bodies. However, in reality, our thoughts and actions could play into metaphors and memories that affected the present. The icons also reminded us that the story of the Okkers family at 7 Joubert Street carries remembrances of dire exclusion: the Okkers family had left Joubert Street for another neighbourhood because they perhaps sensed that they were, after all, not welcome in the town centre when the National Party of 1948 increasingly legislated racially-separated areas.

Through our creation of art on the walls, of encountering ghosts, and of merging image with wall plastering amidst web engineering, we assimilated processes that were futile: The process of departures could not be reversed. Our artwork compelled us to find different mutual ways of being together, and of making music together, in a town layered with harms. Herein, perhaps, lie openings of this research project. Some of Hildegard’s photographs of what resulted as momentary wall inscriptions are included in this article.

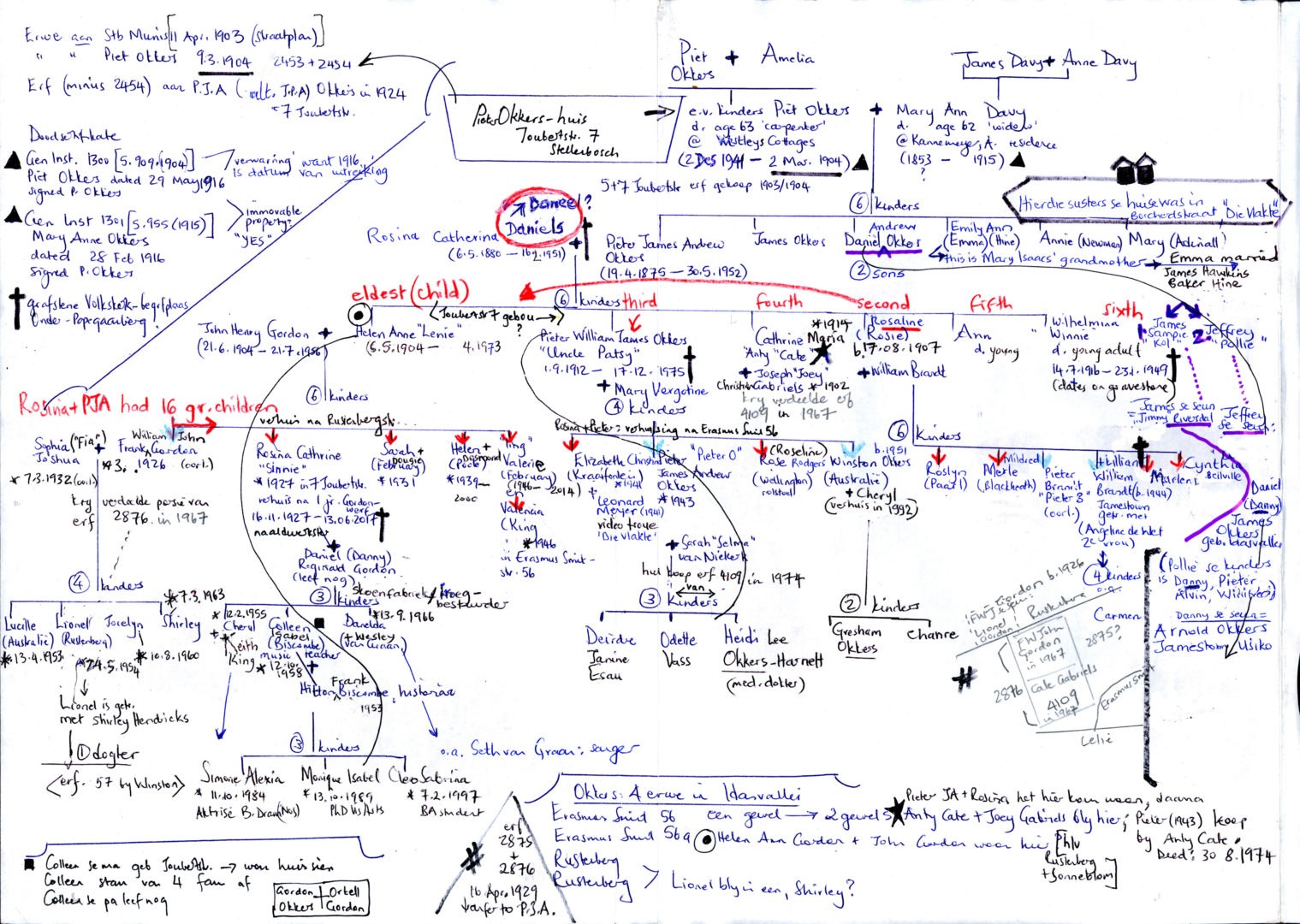

A Family Tree

The first family who made their home at the erf and house on 7 Joubert Street, Stellenbosch were the Okkers family of Stellenbosch. During the course of my research, I drew and redrew the Okkers family tree to attempt to know the family and their connections to one another. This drawing project was made possible by a network of persons who carried memories and who owned archival documents, as well as a host of persons who contributed their knowledge and skill to inform this compilation. [2]Hilton Biscombe, Colleen Biscombe (born Gordon), Monique Biscombe, Pieter Okkers, Sarah Okkers (born Van Niekerk), William Brandt, Angeline Brandt (born De Wet) Elizabeth Meyer (born Okkers), Leonard Meyer, Lize Malan, Wium van Kerwel, Debbie Gabriel, Hannelie Jonker, Karlien Breedt, Makati Kaizer, Donadene Nicolas, Noor Daniels, Lorna Olivier, Jaco van der Merwe, Alta Wagener, Louma Engelbrecht, Francois Swart, Hendrik Geyer, Elsabe Daneel, Henry Daneel, Pieter Conradie and Harold du Toit all helped find or supply information. Africa Open Institute (AOI) is drawn into the life writing of the address, and I want to thank everyone of the music research institute who are continuing to layer the meshwork of stories with work and play. For the inauguration evening of 9 October 2018, AOI persons who helped conceptualise the event were Stephanus Muller, Thembisile Nyathi, Pakama Ncume and Hilde Roos, in particular, as well as many others linked to the institute. Howard Gordon, Grace Bruintjies (both in office at the Lückhoff High, Banhoek Road), as well as a network of artists and caterers became part of the stories that laced around the inauguration. For the process of name-giving of the house, I thank Ronel Retief who first took the process further with a series of meetings held at Stellenbosch University management level, and, thereafter Leslie van Rooi, Michelle Jooste, Michelle Swart and Elmarie Constadius, who designed and produced the wall placard with information about the history of the house. By naming the house ‘Pieter Okkers-huis’, we acknowledge the energies that people bring to place, and the en-housing that place provides for people. For initial discussions about this article, thanks to Julia Raynham. For editing, my thanks to the journal editors Stephanus Muller and Aryan Kaganof. For creative sharing, I wish to thank Garth Erasmus (music-making), Aryan Kaganof (score and film) and Hildegard Conradie (photographs of wall imprints). I also want to thank one of my brothers, Theo Pauw, a hobby woodworker, who donated the piece of yellow wood, and proceeded to graft the name plaque. To Henk Dekker, thank you for mounting the signage onto the stoep wall at the front door of 7 Joubert Street. Finally, a collective thank you to Heidi Okkers (great-grandchild of Pieter James Andrew Okkers and Rosina Catherina (Daniels) Okkers) for undertaking to administrate an Okkers family blog. Heidi Okkers [3] For contributions to the Okkers site, Heidi Okkers can be reached at e-mail address okkersh@gmail.com indicated her willingness to administrate an online blog for the hosting of photographs, documents, stories and memories on the Okkers family, the descendants of Piet and Mary Ann Okkers (born Davy) and Pieter and Rosina Catherina Okkers (born Daniels). [4]Rosina was most probably born Daniels, and not Daneel. (The family tree in this article suggests both options, circled in red, as the tree was drawn up at a time when her birth surname was unconfirmed.) My thanks to members of the Okkers family, and Elsabe Daneel and Henry Daneel, who helped trace the birth surname of Rosina Catherina in the Daneel family registers (e-mails of 27-30 October 2018), and to Jacobus van der Merwe of the Western Cape Archive and Record Services (e-mail of 31 October 2018), who confirmed that Rosina was born Daniels, and not Daneel, although contrary opinions on the matter prevail, based on the memories kept by Ma Sinnie, now deceased. (Van der Merwe’s information was based on records from the Stellenbosch Death Records Register, (ref. no. HAWC. 1/3/44/5/17: entry 35 of 1951). Rosina’s second name was Catherine. Rosina hailed from Piketberg, and her and Pieter’s son, Pieter William James Okkers (‘Uncle Patsy’, born 1912), was also born in Piketberg, as Rosina and Pieter lived in Piketberg for a brief period of their marriage, but returned to Stellenbosch thereafter.

Although I did not create the family trees of people who lived at 7 Joubert Street after the Okkers had left there, such a project may well still be undertaken. The family tree of the Du Toit family, and the ‘Stellenbosch University family’ would then be included, in order to relay a multiplicity of stories, layered through time and through perspective. However, for now, the article engages the most erased history of the address, and brings this story to the fore. (The available information on the Du Toit family, and their neighbours, the Conradie family, as well as the University’s uses of the premises at 5 and 7 Joubert Streets, is included in the text of this article.)

‘Remember to tell people where you got your information from’

I initially compiled these notes for historian and artist Hilton Biscombe at his request. Hilton was making a film on the stories of the people who first lived at 7 Joubert Street, Stellenbosch (Biscombe 2018, A State of Grace). Hilton’s former publications include a book (2006), as well as a film (2006), on the stories that emanate from the immediate lived environment of Joubert Street, known as ‘Die Vlakte’ and the eviction of people from there (and elsewhere) in the 1960s to early 1970s.

Hilton requested that the information, names, dates and documents that related to 7 Joubert Street be compiled for his perusal and reference. Hilton also reminded me of the importance of telling people ‘where you got your information from’ (in conversation with Hilton Biscombe, 30 May 2018). Hilton and his wife, Colleen (born Gordon), and Pieter Okkers and his wife, Sarah (born Van Niekerk)—descendants of the first owners of 7 Joubert Street—provided crucial pieces of information that helped me begin to compile what I call ‘life writing’ (after Kilian and Wolf, 2016) of 7 Joubert Street.

The large-scale relocation of persons, coupled to land seizure that took place in South Africa’s mid-20th century and thereafter, was legislated through the South African ‘National Party’ government’s strategy known as the Group Areas Act, first proposed in 1950 (Giliomee 2007:193) and passed into law in 1952. The Group Areas Act used ‘race’ as a classifier to keep people apart (therefore apartheid) and regulate geo-political and socio-political life within the borders of South Africa: how one lived, and where one lived, and what one was to believe about oneself, was pre-determined and controlled by law.

‘Race’ was notoriously architected to employ visible body metrics as indicators for decisive policing of people’s lives. Prescriptions of race distinction were legislated in The Population Registration Act of 1950. Karen Harris indicates the ‘imprecision’ and ‘unwieldiness’ of this act—an instrument which ‘was amended eight times before it was eventually repealed four decades later’ (Harris 1917:9–10). ‘Race’ classification was designed by persons who felt comfortable to call themselves ‘white’ (‘blanke’, ‘European’) and who decided on the fate of those considered ‘non-white’ or ‘non-European’. The negatively-referred demographic category of the vast majority of people in South Africa was further classified as ‘coloured’ and ‘African’ (‘Bantu’, ‘natives’, ‘plurale’ and other derisive terms). ‘Race’ classification extended to persons of ‘Japanese’ and ‘Jewish’ origin (both classified ‘white’, hereby reinforcing a conflation of race with nation state and ethnic-religious origin). Seven distinctions of ‘coloured’ were identified in Proclamation no. 46 of 1959, with designators such as ‘kleurling’, ‘Malay’, ‘Chinese’, ‘Indian’, etc. (Harris 1917:9). In addition to the above derogatory terms for ‘non-white’ groupings, several other offensive terms, not here listed, also circulated in colloquial references.

Stellenbosch, in the 1940s to 1960s, still held the possibility of maintaining a demographically diverse town centre comprising people of various social strata, backgrounds, ethnic origins, cultural and religious identifications, as well as fluid movement within these. The persistence of the town’s administrators in procuring prize land sites such as the town centre and ‘Die Vlakte’, and reserving these areas for white use, determined the haulages of human cargo that followed. National legislation was a convenient justification for mass evictions, the destruction of intact communities, as well as the removal of people to the far outskirts of town: pockets of land that were severed from the commerce, tourism, academe and community activities linked to spaces in central Stellenbosch. Today the injurious lines of classification continue to infect identity, socialisation, residence, access, opportunities and memory and forgetting.

Life writing a place.

Life writing 7 Joubert Street: a place, an erf, a plot, an address—and its people—unearthed (and continues to unearth) stories about the people who made the place home. In thinking about and sensing the people of a dwelling, I became aware of two things: First, I could not comprehensively delve into the many knowledges and sensings of a family’s biography. Second, I became entwined into a network of persons who remembered, found and related stories about the space, the place, the erf, the immediate area and the socio-political entanglements of past and present within which the dwelling is situated.

As the article grew into a compilation of research, stories, drawings, artworks and creations in sound and on film, I began to think of the life writing of 7 Joubert Street as a Foucauldian ‘anthology of existences’ (Foucault 1979:76).[5]My thanks to Marc Röntsch who first referred me to the notion of life writing as an ‘anthology of existences’, from Foucault’s text (Röntsch 2017:11–12). By using the term life writing, rather than the more formal term ‘auto/biography’ (Röntsch 2017:9–10), and by including diverse registers of formality as well as various creative insertions in this life writing, I was giving substance to Foucault’s notion of compilation that is never final or comprehensive.

This article also posits as praxis emanating from decolonial aestheSis, the latter a term put forward by decolonial scholars Walter Mignolo and Rolando Vázquez (2013), Mignolo and Walsh (2018) and a web of thinkers and practitioners influenced also by the interrogations in academe and art emanating from the so-called Transnational Decolonial Institute since 1998.[6]Curator Alanna Lockward and artists Pedro Lasch, Robby Shilliam and Jeanette Ehlers, as well as independent artist Guillermo Gómez-Peña and his performance troupe Pocha Nostra, are only a few examples of artists emanating from the TDI in the past decade. Mignolo and Walsh further explore the theory and praxis of decoloniality in their joint publication of 2018, which is a first publication in the series titled On Decoloniality.

Decolonial aestheSis works from and towards notions of ‘the senses’ and sensing (Mignolo and Walsh 2018:220). In the words of decolonial scholar, archaeologist and curator Nick Shepherd, decolonial aestheSis through art uses ‘all of the senses’ ‘to move beyond a theory-practice dichotomy’. Decolonial aestheSis is ‘a radical engagement with locality’ that ‘critically reworks […] tradition’ to ask what the ‘stories’ are that ‘lay on the land’—‘this land here and now’. Decolonial aestheSis is therefore about ‘continuity’, ‘recapitulation’ and ‘afterlives’.[7]Phrases quoted are from a transcript of a public spoken response to one of my doctoral research concerts, delivered by Nick Shepherd (Transcript included in Pauw 2015:227–229). The life writing of 7 Joubert Street accesses the nuances that decolonial aestheSis, as an artistic commitment to locality, enables.

Life writing pertains to a person or persons. Kilian and Wolf contend that ‘[l]ife writing can hardly be thought of without its connection to space’ (2016:1). For them, ‘the spatial dimensions of life writing’, or, ‘[t]he spatial turn’ (2016:2), ‘might also be viewed as a response to spatial transformations resulting from historical upheavals and technological developments’ (2016:2). They map space in connection to life writing, and also analyse the role that nostalgia plays. They suggest that ‘nostalgia about places resonates with phenomenological studies that associate place with rootedness, security, personal significance and identity, as opposed to space to which they attribute qualities like openness, freedom and the uprooting of established values’ (Kilian&Wolf 2016:2). They also note how critical geography has problematised the ‘neat separation’ of fixed polarities of a space/place binary (2016:3).

In my project I find no singular sense of rootedness or fleetingness relating to either of the terms place and space. Instead, I find that both of these terms are openings for stability as they are also openings for change. Through my research project I do not find that I am trapped in the fixed notions of nostalgia described by Kilian and Wolf, but I do find emotional attachment: I am overjoyed, for instance, when I am informed in June 2018 that the town’s heritage laws protect the one-gabled homes of 5 and 7 Joubert Streets against demolition. [8]Noor Daniels at the Stellenbosch Municipality (Building Development) confirmed that historic gabled houses in Stellenbosch are protected by heritage law against demolition. The houses at 5 and 7 Joubert Street are therefore under scant threat of demolition (In consultation, 26 June 2018).

‘Dwelling perspective’ and ‘embodied landscape’ that informs music-making

The anthropologist, Tim Ingold, speaks of ‘a dwelling perspective [which] is understood as the forms people build […] within the current of their involved activity, in the specific relational contexts of their practical engagement with their surroundings’ (Ingold 2000:186). Ingold advocates the notion of ‘embodied landscape’ where ‘landscape becomes a part of us, just as we are a part of it’ (Ingold 2000:191). The result is what he calls a ‘web of life’ that is ‘a meshwork of interwoven lines’ (Ingold 2011:63). The embodied landscape of 7 Joubert Street includes people from the past and the present; people who fold into place. The ‘dwelling perspective’ of 7 Joubert Street becomes more layered as the ‘meshwork’ of stories weave back into present-day living. Every time I approached the one-gabled house, walked across the green-painted floor of the ‘stoep’ (porch) and entered at the front door to do my work at Africa Open Institute, I laced into an organic tapestry of connections. I now continue to sense that the walls and the floors and the ceilings of the house carry memory, and stories of life living. I continue to wonder how I am able to make wall-floor-ceiling music to accompany these memories, to voice the remembrances of the Okkers family, to remember the eviction-trauma of the 1960s, to know ambiguously of the dedication of ‘nuclear’ physicists who worked there with atomic formulas and to note traces of a university’s steady mechanisms of institution building.

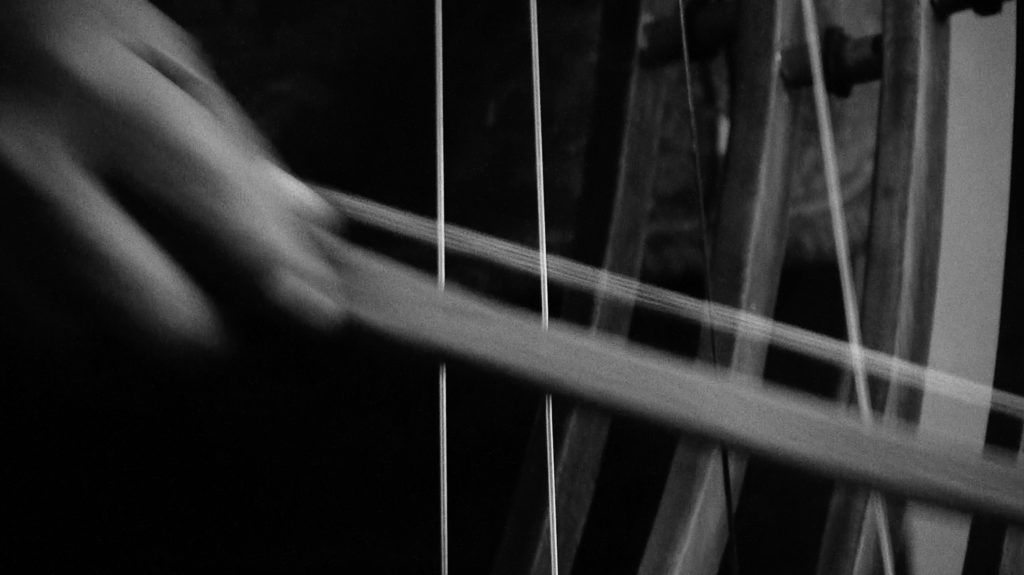

One such music-making project that made ‘wall-floor-ceiling music’, and its accompanying film project that resulted from our music-making, took place in the winter of 2018. Through the project we musicians wanted to respond to Joubert Street as embodied landscape, to engage with its meshwork of stories, thereby creating a dwelling perspective through sound.

A music-making, a film

In order to make music with and against the history of 7 Joubert Street, I asked Garth Erasmus to play with me. Garth recorded our music-making session of Tuesday evening 19 June 2018 on his zoom recorder, and the filmmaker, Aryan Kaganof, came to film the session. Stephanie Vos, a researcher at Africa Open Institute, who happened to drop by, also attended. The music we played was a reading of Kaganof’s score, titled ‘Suiwer’, for flute and indigenous noise music, composed in 2017. We imprinted the nineteen screens of the score of ‘Suiwer’ onto an interior wall of the house by using a data projector.

Our last number, based on Screen 7 from the score, was played on flute (Marietjie) and klariduk (Garth). It was filmed in blue light that radiated from the wall, as the data projector had disconnected from the input source. From the latter, Kaganof produced a 21 minute-film, based on the aesthetics that he engaged in the music score.

Kaganof’s intention had been to work ‘improvisatorially to what was going on, editing in the camera’ (e-mail of 26 June 2018). The film, ‘Suiwer in Blauw’ is the result of being together, caring about where and how we live and work, and of enmeshing into our music-making the stories that intermingle around a family who built two houses in 1926 and 1927.

On seeing the film for the first time, Garth Erasmus wrote: ‘A perfect paean to Joubert Street walls. [This film] exemplified the voices echoing from a deep past and the slowed down pace of the frames turn us [musicians] into statues and the presence of the past becomes statuesque. And the blues. Love how the light slowly begins to glow and grow on a cheek here or the reflective mirroring silver of the flute there makes us still and the light move. Thanks Aryan. I love it […] And as to the instrumentation just one thing… it’s the flutes but also the other horn [… that] I call the KLARIDUK (a mix of clarinet mouthpiece on a Duduk—the Kurdish folk instrument which I’ve altered)’ (e-mail of 27 June 2018).

7 Joubert Street: History: ‘Onbekend’ (Unknown)

As I embarked on finding out more about 7 Joubert Street, I followed various avenues. These included queries directed to the Stellenbosch Heritage Foundation, the Stellenbosch Heemkring (both had no information pertaining to the address), and the Stellenbosch Museum Archive in Erfurthuis. (The Stellenbosch Museum Archive manager, Debbie Gabriel, and archivist, Hannelie Jonker, indicated in great detail where I would possibly find information: e-mail from Hannelie Jonker, 6 Nov 2017.) I telephoned seven departments at the Stellenbosch Municipality, including that of Makati Kaizer at the Heritage Planning section, and he indicated leads that I could follow.

The Stellenbosch University Facilities Management website contained an Excel sheet of its properties accessed 2 November 2017). Under the address of 7 Joubert Street was listed an Entry number (193), a Building code (846), the Erf number (2453), and under the rubric ‘History’, the entry read ‘onbekend’ (unknown).

‘Bekend’

(Known)The remainder of this article sets out the ‘known’ aspects of the address that surfaced. Documents such as university purchase contracts, minutes of meetings, allotment plans, title deeds and building plans indicated information about the address. Interviews with people, books on local history, death certificates and the tracing of a family’s migration from Joubert Street to Erasmus Smit Street and Rustenburg Street revealed information about a family. The more recent history of the two single-gabled Joubert Street houses also surfaced, and some of this history is presented as (what I call) ‘Interludes’.

Wium van Kerwel of Stellenbosch University Facilities Management sent me a copy of the purchase contract of the house in 1973, when the university bought the house from the previous owner, a Harold du Toit, born 1926. The contract carried two signed dates, namely 25 June 1973 and 11 July 1973 (e-mail of 6 November 2017).

The purchase contract also contained a house plan sketch (with details on the condition of the house at the time). When I e-mailed the Stellenbosch University Senior Archivist, Karlien Breedt, she provided me with extracts from four sets of minutes from the university’s Council Meetings and Senate Meetings (she referred to the documents as ‘Raad- en Senaatstukke’ in the e-mail of 3 November 2017). The earliest of the archived documents confirmed the purchase of 7 Joubert Street for ZAR19 000 (Stellenbosch University Archive 1973a), whereas the later documents noted decisions about the property taken between 1973 and 1980 (Stellenbosch University Archive 1973b, 1977, 1980).

P. Okkers

When a heritage consultant and friend, Lize Malan, sent me a plot allotment plan of 1903 (from the surveyor general database), the name of a person, first connected to the address, was revealed: ‘P. Okkers’ (e-mail of 6 November 2017). Lize then took me to the Cape Town Deeds Office, and these records, compared with records from the Genealogical Institute of South Africa (GISA) in Banhoek Street, [9]Incorrectly also referred to as ‘Banghoek Street’. The ‘ban’ refers to the mosque at the bottom of Banhoek Street. See Biscombe 2006:13. Stellenbosch, and the help there of Lorna Olivier, proved to be crucial. Name and date inscriptions on GISA microfiche records of the death certificates of Piet Okkers and Mary Ann Okkers (born Davy), issued just over a century ago, connected to deeds of land transfer, revealed something of a ‘dwelling perspective’ of 7 Joubert Street.

Eight months after my initial research of 2017, and in June 2018, I consulted the first building plans of 7 Joubert Street (submitted by ‘Mr P. Okkers’, accepted 1 November 1927). The file at the Stellenbosch Municipality also held plans for building alterations of 1955 (submitted by Du Toit) for an ‘enclosing of back stoep’ and of 1973 (submitted by University of Stellenbosch) for new bathrooms (on which the latter plans refer incorrectly to Erf 2454, canceled and changed to Erf 2453). The 1927 plans were a joy to find: an artistic delight of hand sketches with water colours seeping onto the overleaf of tracing paper—and the finds were again ‘lucky’, given how old they were. I am indebted to Donadene Nicolas and Noor Daniels of Building Development at the Stellenbosch Municipality for their help. I was reminded of the physical ‘enmeshment’ of housing, home and landscape when I read that the ‘proposed house for Mr J.A.P. Okkers’ [10]The Stellenbosch Municipal Council building plans of 1927, as well as the entry in the Cape Town Deeds Register of 1924 indicate P. Okkers as J.A.P Okkers (and refer to James Andrew Pieter Okkers, born 1875). On the gravestone of P. Okkers, who died in 1952, the initials are listed P.J.A (Pieter James Andrew). I have decided to use the latter order of initials (as used on the gravestone) throughout this article. This decision is motivated in part by the knowledge that this is how his descendants remember him, as related by his grandson, also named Pieter James Andrew Okkers (born 1943). indicated Municipal Council specifications for the dwelling that included:

concrete, cement, brickwork, mortar clay, lime plaster, 3-ply asphalt, galvanised iron.

7 Joubert Street, 1903–1973

For all the traceable documents, it was moreover the remembrances of the descendants of the Okkers couple, and the cups of tea that they shared with me, that brought to the fore a meshwork of embodied place.

In 1903 the Stellenbosch Municipality subdivided municipal land for 98 plots to the east of Ryneveld Street in the north-running streets exiting from Merriman. [11]Formerly known as ‘Van Ryneveldt Street’ (Biscombe 2006:4). Biscombe comments that group area strictures achieved the erasure (of former names and spellings) from communal memory, as in the case of the current (incorrect) usages of ‘Ryneveld Street’ and ‘Banghoek Road’. He noted, to me, ‘Even that was taken away’ (In conversation with Hilton Biscombe, 28 June 2018). These streets were De Villiers, Smuts, Joubert, Van der Byl, De Beer and Bosman Streets. On a drawing of the ‘Government Land Surveyor’, ‘framed from Actual Survey of 20 September 1903’, plots 30 and 32 are listed as ‘Deducted’ against the name of ‘P. Okkers’ (on 14 November 1903). P. Okkers therefore laid claim to, and purchased, two plots, consolidated as one erf, in 1903. Official transferral documents in the Cape Town Deeds Register offices are entered as ‘Transferred’ from ‘Stellenbosch Town Council’ to ‘Piet Okkers’ on 9 March 1904 (Title Deed Erf 2453, entry 2686).

The land surveyor map of 1903 reveals information that dates back to March 1887. The neighbours of the Okkers, after the September 1903 survey, were apparently T. Newman, W.B. Hurit, W. Fothergill, F. Africa, H.H. Gird, P. Hartogh, B. Bergsteedt and D.F. Bosman. Some of the information that this surveyor document reveals includes an array of dates, names, and numbering systems.

The numbered plots, related to their first owners, provide a visual map of the street’s potential first community, as shown in my sketch, hereafter. The two Okkers plots are on the left (west) side of Joubert Street, third and fourth up from Merriman Street.

I found the handwriting on the 1903 document unclear in some cases, but an online search of genealogical records indicated the most plausible spellings for some of these surnames. The South African surnames are therefore probably: ‘Fothergill’ (and not Fathergill), ‘Gird’ (and not Gira), ‘Hartogh’ (and not Harlogh). ‘Bergsteedt’ and ‘Bergstedt’ are both in use as South African surnames (online search, 23 July 2018).

Twenty years later, in 1924, the Okkers family divided the then-vacant property into two. In 1924 the title deed of Erf 2453 (the original plot 32) indicated a transferral of the one section to the son of Piet Okkers, namely Pieter James Andrew Okkers, on 27 March 1924 (Title Deed Erf 2453, entry 2453). The ‘remainder’, 5 Joubert Street (the original plot 30), was later transferred to a ‘Stephanus Abraham Conradie’ in 1940 (transferral registered on 30 December 1940, Erf number 2454 allocated).

Before transferring the property to Conradie, 5 Joubert Street was the first house of the Okkers family: Pieter Okkers applied for approval to build a new home at 5 Joubert Street in 1926, and when, in 1927, he applied to build the second home at 7 Joubert Street, the address that he indicated on the second application was ‘P. Okkers, Joubert Street’. He was therefore already a resident of the street when he erected 7 Joubert Street.

Having sold 5 Joubert Street in 1940, the Okkers family sold 7 Joubert Street to Harold du Toit at the end of almost five decades of ownership, late in 1950 or early in 1951 (transferral registered on 24 January 1951, Title Deed Erf 2453, entry 846). The Okkers family owned, by then, four properties in Ida’s Valley,[12]In Afrikaans this Stellenbosch neighbourhood is known as ‘Idasvallei’. For an overview of the history of this valley and neighbourhood, see Ontong 2017:16–35. notably in Erasmus Smit Street and in Rustenburg Road. One of the four properties is still owned by the family (with owners Pieter and Sarah Okkers). The Okkers family (or some or all of them) had probably relocated and lived in Ida’s Valley since the 1940s. In all probability they retained 7 Joubert Street as a rental property in the last decade—before selling it in 1951. These are details that we do not know, and we can only speculate on some of the answers—answers that include the knowledges that bodies carry about lived dwelling places within the space of systems of race classification and forceful exclusion.

What we do know is that Harold du Toit enclosed the back stoep (as the approved building plans of 22 November 1955 indicate) and ultimately sold the property to the University of Stellenbosch in 1973, with the transferral registered on 9 October 1973 (Title Deed Erf 2453, entry 29654). The University of Stellenbosch altered the building by adding new toilets and a bathroom at the back (door) exit of the property, with plans approved on 17 October 1973. Somewhere between 1973 and the present, the kitchen (initially the third room on the left from the entry portal) was moved towards the back of the building (western side). The new kitchen (later called the ‘spens’ (pantry) on the 1973 plans) was designed in the area that was formerly allotted as bathrooms for women personnel. These interior refurbishments are not indicated on the plans that the university provided me with in 2017, and are also not included in the plans housed at the municipality. Needless to say that the sale transaction of 1973, from Du Toit to Stellenbosch University, is the link for our music institute’s relation to the Okkers family.

An over-reaching stamp: ‘Blanke’

We do not know why the Okkers family sold their home in 1951. We do know that the deeds register entries for 7 Joubert Street carries an official stamp, on the far right of the page: The stamp, signed 24 August 1962, visually encroaches onto the prior entry of 1924—the entry that had declared Pieter James Andrew Okkers the owner of the property, after transferral from his parents’ estate. The over-reaching stamp proclaims that the ‘Group Area’ is ‘blanke’ (white).

We know that the Okkers family were not part of the formal evictions known as ‘Die Vlakte’ expulsions. We know that Joubert Street was on the eastern boundary of Die Vlakte, one of the areas in Stellenbosch that was subsequently reserved for white ownership and use in 1964.

Die Vlakte, 1824-1964

Joubert Street is included in the hand drawn map (by S. Felmore/ Fuad Biscombe), included in Hermann Giliomee’s book, Nog altyd hier gewees (Giliomee 2007: after p 126). On this map the building at 7 Joubert Street is not listed as one of the important buildings (‘vernaamste geboue’) in Die Vlakte.

Die Vlakte has a history that connects to slavery, slave executions as well as ‘free slaves’. According to Giliomee, mention of ‘die vlakte’ (the field) in historiography refers to the area where, in slavery times, slaves were executed (Giliomee 2007:5–6). Executions took place as late as 1824 on ‘die vlakte naby die dorp’ (the field near the town), in this case ‘die klipvlakte noord van Pleinstraat tussen Ryneveld- en Andringastraat’ (the stony field north of Plein Street between Ryneveld and Andringa Streets) (Giliomee 2007:6). If taken literally, and for the time period indicated, this field is to the west of what would later become Joubert Street.

Giliomee notes that the end of slavery (1838, following on from the four-year period when ‘freed slaves’ of 1834 still worked for former ‘masters’) gave rise to many houses erected by and for emancipated families—families who no longer lived on premises of former masters (2007:56). During the 1840s and 1850s single and duplex homes in Die Vlakte, erected on both sides of Merriman Street (formerly Berg Avenue), came to be seen as the ‘District Six’ of Stellenbosch (as described by historian Hans Fransen) (in Giliomee 2007:57) and relayed by Matt Segers (in Biscombe 2006:xix). The expansion also coincides with the development plans (in 1859) of Carl Otto Hager, when Andringa and Ryneveld Streets were developed to the north, so that Merriman Street was first laid out. By the 1930s and 1950s numerous families lived in Die Vlakte, and businesses, schools and churches, as well as the Mosque in Banhoek Street, thrived.

The demography of people living in Die Vlakte until the 1960s portrayed a racially, religiously and socially diverse composition. However, the initial national legislative submission of the so-called Group Areas Act was made in 1950 (Giliomee 2007:193) and the first implementation of forcibly removing twelve families who lived around the Braak in central ‘historic’ Stellenbosch occurred in 1954 (Giliomee 2007:198). In 1962 Die Vlakte was still a controlled area (‘beheerde gebied’) where an assortment of social strata was tolerated (Giliomee 2007:199). The geographer, Barnie Barnard, notes that the Stellenbosch town council was ‘unenthusiastic’ about the full implementation of the Group Areas Act, and delayed rigid enforced segregation by fourteen years, partly because ‘ “coloured” property owners still had municipal voting rights’ (Barnard 2004:22). However, in 1964, the national Department of Community Development took charge of matters, and the area was declared a ‘white’ area, set-off from the so-called ‘coloured’ areas of Cloetesville and Idasvallei and the so-called ‘black’ township of Kayamandi by ‘broad buffer’ zones that Barnard describes as ‘institutional land which accommodated the municipal nursery and fire station, a bus depot, two government research stations and, in the case of Kayamandi, railway land’ (Barnard 2004:23). Barnard also notes that the ‘low status white residential suburb of Stellenbosch North’ served as another buffer zone that only began to be ‘colour blind’ in the early 2000s (Barnard 2004:26).

The memories of slavery, of executions of slaves, mass legislated evictions (and of a family quietly selling their property in 1951, one year after the Group Area legislation was set in motion) forms a dire hauntology to Die Vlakte and around 7 Joubert Street.

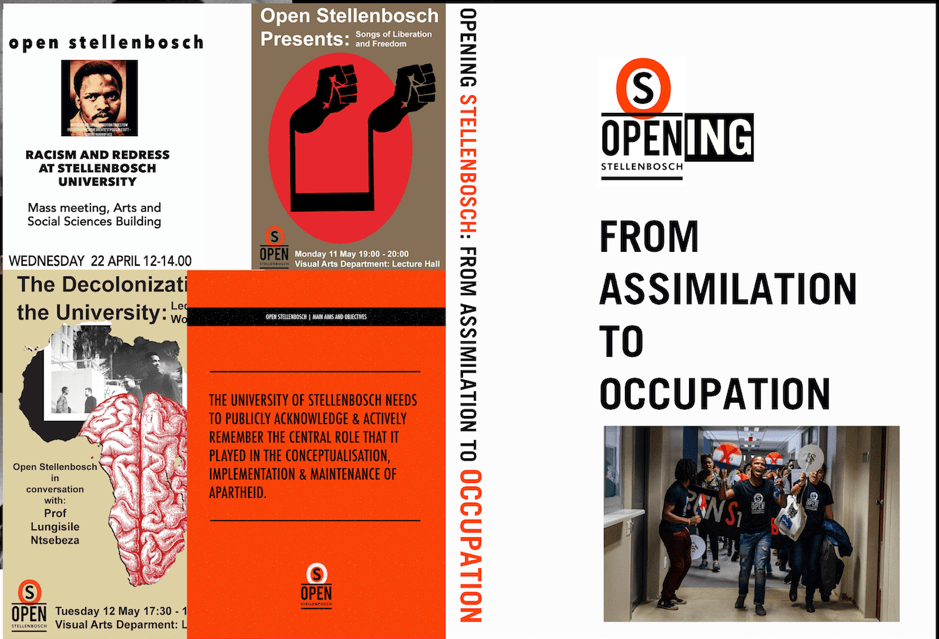

‘In ons bloed’: A ‘Stamped’ embodied landscape

After 1964 the mosque near the junction of Andringa and Banhoek Streets was left intact as a building (still) in use, but several churches changed ownership. The Volkskerk building, for which the brick-laying ceremony was held on 12 October 1929, changed hands, and Volkskerk Primary School (erected by the Volkskerk members and inaugurated on 2 March 1924), as well as the Volkskerk pastor’s home, were torn down. Saint Mary’s (Anglican) Primary School and the Dutch Reformed Sendingkerk School (the latter was next to the current Baptist Church beside ‘Pick’nPay’ mall) were also demolished. The remaining schools in the area, Lückhoff High, Methodist Primary School, James Hugo Gedenkskool Laerskool, and Rhenish School, were transferred to new owners. The two cinemas, ‘Gaiety’ and ‘Empire’, and businesses and shops, were closed and gutted, and people were moved to Ida’s Valley, Cloetesville and elsewhere (Biscombe, 2006: 211–213, etc.). Hilton was 16 years old when he and his family had to move from Van Ryneveldt Street. Today he describes communal experiences of trauma as a disease that nestles and lodges, forever, ‘in our blood’. Hilton Biscombe’s book (In ons bloed, 2006), as well as the 20-minute film he made to accompany that publication (2006), tells of this trauma that infests ‘the blood’ of a community—always to retain circulation in bodies. He also tells me of his memories that have infected his own blood and have made him physically ill.

In 1926 Pieter Okkers lived in 92 Andringa Street at the time of his application for approval of his first new home at 5 Joubert Street (later to become Erf 2454). The letter of approval, signed by the Town Engineer on 27 January 1926, is addressed to ‘Mr P. Okkers, 92 Andringa Street, Stellenbosch’. I went to look for 92 Andringa Street, and found that the house does not exist anymore: It has been demolished, over-reachingly ‘stamped over’ by the imprint of the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences (FASS) building,[13]Formerly known as the B.J. Vorster-building on the University of Stellenbosch campus. a large 6-story structure of the university. (The FASS building used to be white-washed. I notice that it is now painted beige.) The ‘Blanke’ stamp in the deeds register, as well as the ‘Building’ stamp on Andringa Street, are a result of powerful successful social engineering. In the context of the subject area of arts and social sciences, these two impressions are a reminder of the need for critical social theory and artistic interventions from scholars and artists who live in the aftermath of these stamped documents and over-stamped embodied landscape.

Reminders such as Hilton Biscombe’s publications, and interventions by a university activist group such as Open Stellenbosch (who were prominent on campus in 2015–2016), brought to acuity the significance of Die Vlakte as an area between the mosque, the Stellenbosch University Engineering Faculty building and the Faculty of Social Sciences building. A few student bursaries (donated by the university rector), a permanent historical exhibition (in FASS), a historical exhibit in a ‘memory room’ in the Wilcocks building (this exhibit dislodged after three years when the university instead exhibited centenary regalia), an exhibit of photographs and certificates in the hallways and Uitstyglokaal of (former) Lückhoff High School and occasional walking tours (such as the one organised by the Gallery of the University of Stellenbosch (GUS) in 2017) are but surface mentions that scrape together a dwelling perspective within which a damaged organic meshwork remains deeply grafted.

Lucky finds: P. Okkers, and Pieter James Andrew Okkers

I return to the excavation of stories as to who ‘P. Okkers’ (buyer of Plots 30 and 32), and ‘Piet Okkers’ and ‘Pieter James Andrew Okkers’ (both indicated in the Deeds Register) are. I ask how they are related to one another, to the wider Okkers family, and how they relate to 7 Joubert Street.

In researching these questions, I again had immense luck.[14]Colleen Biscombe suggests to me that this is providence—organised by her mother ‘from the other side’ (In conversation, 28 June 2018). I sent an e-mail to the historian, artist and former teacher, Hilton Biscombe, on 1 November 2017. (I had previously contacted Hilton in 2015 about the history of ‘Roesdorp’, Stellenbosch, in response to one of his book publications. See Biscombe 2006: xxiii-xxiv.) When I mentioned ‘P. Okkers’ to Hilton, he suggested that this name referred to Pieter James Andrew Okkers (1875–1952) (e-mail of 7 November 2017). Hilton gave me two providential leads:

Lead 1: Pieter James Andrew was the great-grandfather of his own wife, Colleen Biscombe (born Gordon, 1958). And more: Colleen’s mother, Rosina Cathrine (Sinnie[15]Sinnie is portrayed on the wall plaque at the Lückhoff School (Banhoek Road) photo exhibition of the school and of Die Vlakte, where a photograph of her and Bettie Luiters are shown in a dramatic production, titled ‘Desert Song’. Sinnie is the woman sitting, and Bettie is pictured standing. Bettie Luiters became the primary school teacher of Colleen Biscombe. Colleen remembers her 6 and 7-year old classmates listening to a popular children’s radio programme of the time, when announced by the Headmaster over the ‘intercom’: The school then listened to ‘Siembamba’ (In conversation with Colleen Biscombe, 28 June 2018). ) (also born Gordon, 1927–2017), was born in Joubert Street, in one of the identical ‘een-gewel huise’ (‘single-gabled houses’). Colleen suggested that, given circumstances, she was most probably born with the assistance of a midwife who came to their home (In conversation with Colleen, 28 June 2018).

Lead 2: Pieter James Andrew Okkers (born 1943), the grandson of Pieter James Andrew (1875–1952), resided at Erasmus Smit Street in Ida’s Valley.

I had also come across Arnold Okkers, Executive Director of Usiko Stellenbosch, a youth programme in Jamestown. In e-mail conversations he confirmed that he was the son of Daniël James Okkers (deceased twenty years before), who had grown up in Ida’s Valley. Arnold was unsure as to whether his ancestor was ‘James’ (second son) or ‘Daniël’ (third son) of Piet Okkers, but was intent on investigating (e-mail, 13 November 2017).

A visit to Pieter Okkers and Sarah Okkers in November 2017 confirmed family names, and provided a photograph of Pieter’s grandfather, after whom he is named. In our conversation we did not verify exact dates. At a subsequent visit in May 2018, Pieter, Sarah and I discussed the possibility of naming the house after the initial entry in the deeds register, ‘Piet Okkers’, the person who had first purchased the land. When I consulted the death certificates of Piet Okkers and Mary Ann Davy Okkers (born Davy), more information came to light that made us change our minds about whom to name the house after. The death certificates at the Genealogical Institute of South Africa (GISA) in Banhoek Street, Stellenbosch, indicated their parents’ names, as well as their children’s names. The certificates are both signed by ‘P. Okkers’ (their eldest child of six children, i.e. Pieter James Andrew).

- Name of the deceased: Piet Okkers

- Birthplace and nationality of the deceased: Coloured

- Names and addresses of parents of the deceased:

Father: Piet Okkers | Mother: Amelia Okkers

- Age of the deceased: 63 years

- Occupation, in life, of the deceased, or if a woman, of her husband: Carpenter

- Ordinary place of residence of the deceased, or if a woman, of her husband: Stellenbosch

- Married or unmarried, widower or widow: Married

(a) Name of surviving spouse (if any) and whether married in community of property or not: Mary Ann Okkers born Davy

(b) Name, or names, and approximate date of death of pre-deceased spouse or spouses: —

(c) Place of last marriage: Stellenbosch

- The day of the decease: 2 March 1904

- Where the person died: Wistleys Cottages, Van Ryneveldt Street, Stellenbosch

- Names of children of the deceased and whether majors or minors:

Pieter Okkers | James Okkers | Daniel Okkers | Emma Hine, b. Okkers | Annie Newman, b. Okkers | Mary Adinall, b. Okkers

- Has the deceased left any movable property? No

- Has the deceased left any immovable property? Yes

- Is it estimated that the Estate exceeds ₤300 in value? No

- Has the deceased left a will? Yes

Dated at Stellenbosch on the 29th day of May 1916.

Signature P. Okkers

Son of the deceased, present at death and funeral.

1. Name of the deceased: Mary Ann Okkers a widow, born Davy

2. Birthplace and nationality of the deceased: Coloured Stellenbosch

3. Names and addresses of parents of the deceased:

Father: James Davy | Mother: Anna Davy

4. Age of the deceased: 62 years

5. Occupation, in life, of the deceased, or if a woman, of her husband: Carpenter

6. Ordinary place of residence of the deceased, or if a woman, of her husband: Stellenbosch

7. Married or unmarried, widower or widow: Widow

(a) Name of surviving spouse (if any) and whether married in community of property or not: —

(b) Name, or names, and approximate date of death of pre-deceased spouse or spouses: Piet Okkers: 2/3/1904

(c) Place of last marriage: Stellenbosch,

8. The day of the decease: 6 November 1915

9. Where the person died: Residence of A. Kannemeyer, Stellenbosch

10. Names of children of the deceased and whether majors or minors:

Pieter Okkers | James Okkers | Daniel Okkers | Emma Hine, b. Okkers | Annie Newman, b. Okkers | Mary Adinall, b. Okkers11.

Has the deceased left any movable property? No

12. Has the deceased left any immovable property? Yes

13. Is it estimated that the Estate exceeds ₤300 in value? No

14. Has the deceased left a will? Yes

Dated at Stellenbosch the 28th day of February 1916.

Signature P. Okkers

Son of the deceased, present at death and funeral

By correlating the death certificates and the information from the Deeds Register Office in Cape Town, the conclusion I drew was that Erf 2453 was transferred on 9 March 1904 to Piet Okkers (1841–1904) one week after his death on 2 March 1904. He therefore could not have built the house at 7 Joubert Street. Pieter James Andrew, his first-born (1875–1952) was the most likely builder or owner-builder and subsequent owner.

The significance of this correlation is that we had to reconsider whom to name the house at 7 Joubert Street after. At the end of 2017, I found a reference on the internet to the estate of Piet Okkers, with his date of decease inaccurately indicated as 1916, and therefore my incorrect assumption that it would have been Piet who built the house, allowing for a substantial period of time after the purchase of the property in 1903. At the Africa Open Institute (and in discussion with Pieter and Sarah Okkers) we concluded that the house be named ‘Piet Okkers-huis’, and I lodged a first application to the university on 9 May 2018. However, as the retrieved death certificate confirmed (received one week after sending away the application), Piet Okkers had died in 1904 and not in 1916. The confusion had arisen because his certificate was issued by the Master of the Supreme Court twelve years after his death, on the implementation of the so-called ‘Adminisatration of Estates Act, 1913’, as well as after the death of his spouse, when the Okkers estate administration had to be put into motion (as confirmed by Jaco van der Merwe, Western Cape Archives and Records Services, e-mail 20 July 2018). The date of death on the death notice is indeed indicated as 2 March 1904. At AOI, and in consultation with the Okkers family, we then had to reconsider the naming of the house, and made plans to approach the university in the light of this new information. The house, we suggested, had to be named after Pieter James Andrew Okkers—the same person that Hilton had first suggested to me when he heard of ‘P. Okkers’ mentioned on the 1903 land surveyor general’s document.

The information was further confirmed when I saw the first building plans of the house at 7 Joubert Street, Erf 2453. The folder containing the plans included a typed letter on blue-tinted tracing paper dated 4 November 1927, signed by the Building Inspector (surname illegible), and addressed to Pieter Okkers, Joubert Street.

4th, November 1927,

Mr J.A.P. Okkers,

Joubert Street,

Stellenbosch.

Re. Building Plans for New House

Dear Sir,

I have the pleasure to inform you that the above plans have been passed and that you pay the water charge of ₤6 before you commence with the work.

The duplicate plans can be obtained at this office on production of the receipt for the water charge.

I wish to inform you that drainage must be installed at the above premises, and therefore you must please submit plans for same reason.

We are prepared to do the drainage plans for you with your permission and at the usual rates.

Yours faithfully

HBB—

Building Inspector

The Okkers family at 7 Joubert Street (and what we know, in 27 points with interludes)

We know that Piet Okkers (1841-1904) never lived at 7 Joubert Street. We don’t know where his wife, Mary Ann, born Davy, a widow as from 1904, resided, except that she died at the residence of A. Kannemeyer (corner of Merriman and Andringa Streets), Stellenbosch, on 6 November 1915, aged 62.

We know that the building plans for 7 Joubert Street were accepted in November 1927, and the house built thereafter, when Pieter Okkers indicated his address as ‘Joubert Street’. We know that the plans for 5 Joubert Street were approved one year and ten months before the plans of 7 Joubert Street were approved, and that, at the time, Pieter Okkers gave his address as 92 Andringa Street, a residence subsequently demolished to make room for the FASS building (in use as from 1981).

Colleen Biscombe owns photographs (of what we presume are the house or houses) that date from 1926 and 1927. We know that the two houses at 5 and 7 Joubert Street had been erected by 1938. An aerial photograph taken in 1938 shows the roof structures to be similar. Both houses also have similar single gables and front porches as viewed from the street. The houses have identical floor plans, as submitted in 1926 and 1927. The builder of these two addresses had apparently built twin houses for the Okkers family, and today these houses are not separated by a fence or wall. Pieter Conradie remembers that there was a fence between the two, with space on both sides for vehicle entrance, and that a lush (grape) vine trellis grew on their side of the partitioning (In conversation with Pieter and Anna Conradie, 12 September 2018).

We know what the first architectural plans of both of the houses at 5 and 7 Joubert Street looked like. The Stellenbosch Municipality (Building Development) holds plans dated 1927, 1955 and 1973 for 7 Joubert Street. There are plans dating from 1926, 1941, 1977, 1983, and 1995 for 5 Joubert Street (Erf 2454). (The plans of 1977 may be incorrectly filed, as I explain further on.) The plans for 5 Joubert Street are all approved, except for the plans of 1995 which propose a double-storey building development across Erf numbers 2454, 2455 and 2456. The history of 5 Joubert Street includes as its legal owners the family Okkers, the family Conradie, and the University of Stellenbosch. The houses at 5 and 7 Joubert Street are gabled structures, and are therefore not under threat of demolition according to current local heritage rulings.

The 1977 plans (incorrectly filed with 5 Joubert Street) indicate an application for the enlargement of windows. This is apparent in the windows at 7 Joubert Street: Wooden-framed widows are the original windows, whereas steel-framed windows are the new windows. The large window underneath the gable of no. 7 (photograph included in this article) is therefore a recent addition (in 1977).

We know that Pieter Okkers (1875–1952) and his wife, Rosina Catherina Okkers (Daniels) (1880–1951), lived at 5 or 7 Joubert Street, or (with their adult children) in both. In the present family they are referred to as ‘Pappie Okkers’ and ‘Mammie Okkers’ (In conversation with Colleen Biscombe, 28 June 2018).

First Interlude: 5 Joubert Street, and the Conradie family

The building plans for 5 Joubert Street, brought into correlation with the information from the Cape Town Deeds Register, provide the following dates and names of owners for 5 Joubert Street, Erf 2454 (an erf which came into existence in 1924 when the original double erf (2453) was subdivided, as noted in the Cape Town Deeds Register, transferral registered on 27 March 1924).

The plans for the proposed home of ‘Mr J.A.P. Okkers [address 92 Andringa Street]’, submitted on 31 December 1925, were approved on 27 January 1926 (Stellenbosch Municipality Building Development plans repository).

The property was sold to Stephanus Abraham Conradie in 1940 (Cape Town Deeds Register, transferral registered on 30 December 1940). Plans submitted by Mr S.A. Conradie, with address given as ‘Van Ryneveldtstraat, Stellenbosch’ were approved on 22 January 1941. These plans indicate a new garage, storage room, and alterations to the back porch (‘stoepkamer’) (Stellenbosch Municipality Building Development plans repository).

The property was thereafter transferred to the only children of Conradie, two sons, Friedrich Gustav Conradie (born 8 November 1934, a diplomat), and Pieter Daniel Gustav Conradie (born 24 November 1941, a minister in the Dutch Reformed Church). A comment in the Cape Town Deeds Register notes that they are ‘albei blank’ (both white). The Conradie brothers managed the property as source for rental income after the death of their mother, Anna (as Friedrich resided in Europe as a diplomat; and as Pieter lived in Potchefstroom-Oos, 1974–1987 (and Overkruin, Wonderboom Pretoria 1987-2008) as church minister, according to the Conradie family register, http://www.dieconradies.com/geslagsregister.htm). Stephanus Abraham (Braam) Conradie, son of Pieter Conradie, confirmed that his father still resided in Overkruin (e-mail of 24 June 2018). I contacted Pieter Conradie, and he seemed pleased to confirm the above, and talk of his memories (e-mail of 25 June 2018, and telephone conversation of 26 June 2018 and thereafter).

Pieter Conradie’s memories: Pieter lived in the house at 5 Joubert Street for 26 years until he left Stellenbosch to begin a career as church minister. 5 Joubert Street is where he grew up from being a school boy in ‘Sub B’ (Grade 2), to being a student in theology. His two eldest children (of four) came to visit his parents there as well. As a six-year-old boy he remembers how his father (Stephanus Abraham Conradie, 1885–1987) purchased the house. His father ‘sat across from a man, a builder, who had built and owned the house’ (this is Pieter Okkers). His father ‘counted out a stack of ₤700 in pound notes’ to pay for the house. Pieter (Conradie) noted that their family had lived in Van Ryneveldt Street (where the University Education Faculty is now built) and then moved to 5 Joubert Street in the 1940s. He remembers Joubert Street as a clay road that became muddy in wintertime. His father was a shoemaker, who had a shop on the corner of Church and Andringa Streets. He also put new strings on tennis rackets. (He remembers that his father put new strings on Dr Verwoerd’s racket, and Verwoerd did not have enough money, so he was given the racket ‘on appro’, By, Die Burger, 21 July 2018.) Pieter confirmed that his father, Stephanus, died at the age of 94 (1886-1980) and that his mother (Anna Louisa, born Mouton, born 1905), lived at 5 Joubert Street until her death, aged 89, in 1994. As her sons moved into their respective careers, and as rooms became available, she leased rooms to students. Pieter Conradie of Overkruin notes that he drives past or visits the front porch of their former home every time he visits Stellenbosch. It is the place he most associates with a sense of ‘home’ in his life.

Pieter Conradie’s reflections: When I told Pieter of the contextual history of their address he realised the significance of his father’s 700 pound-deal with the recipient, namely that his family’s purchase of the house in Joubert Street stood under the token of race-based transformation of place. In 2018 Pieter wrote to me of having had to attend compulsory Wednesday morning-lectures on topics such as ‘die regverdigheid van ons rassebeleid’ (the fairness of our race laws) when he was a chaplain serving in the South African Defence Force/ Army from 1970–1974. He comments, ‘Soos ek oor die Okkersgesin voel, voel ek vandag oor daardie lesing’ (I feel the same sense [of betrayal] when I think of the Okkers family, and of those lectures) (e-mail, 29 June 2018).

In September 2018 Pieter and Anna Conradie visited Pieter and Sarah Okkers at their home in Erasmus Smit Street and had tea together. Pieter and Anna also came to 7 Joubert Street for tea (while Leonard Meyer was visiting to bring us a photograph of Pieter Okkers) and one of the students residing at no. 5 took the Conradie couple and Loenard Meyer through the Okkers/Conradie home at no. 5. Pieter noted that that the bountiful fruit trees no longer existed (except for the remains of a quince stand to the south of the house) and that the garage structure in the back yard had been demolished. He did not recognise the row of ten student rooms built in the back yard (now called 5a Joubert Street) (In conversation with Pieter Conradie, 12 September 2018).Today the house is one of the properties for student housing within the Listen, Live and Learn Initiative (LLL), whereby students are grouped according to study and social interests. The house currently accommodates four students (In conversation with Andries de Jager, a final-year engineering student and resident of the house, 7 September 2018).

The Okkers family at 7 Joubert Street, continued

The Okkers children had all been born before the houses at 5 and 7 Joubert Street were built. We assume that they resided at 92 Andringa Street, the address that their father indicated (for the approval of building plans in 1926).

We know that Pieter and Rosina had six children, with names, and dates:

Helen Anne (Lenie) (Gordon) (1904–1993)

Rosaline (Rosie) (Brandt) (1907–2000)

Pieter William James Okkers (Uncle Patsy) (1912–1975)

Cathrine. [16]The Deeds Register carries an entry in 1967, which refers to ‘Cathrina Maria’ (as the subsequent owner of 56 Erasmus Smit Street, at the death of her husband, Joseph Christian Gabriels). However, Aunty Kate’s sister’s child, who most probably carries her name, was called Rosina Cathrine (Sinnie), leading me to the conclusion that the deeds register entry is incorrect, and that ‘Cathrine Maria’, instead, is the correct version. Aunty Kate is the godmother of Colleen Biscombe, and it is through her that Colleen acquired many family photographs. Maria (Aunty Kate) (Gabriels) (1914–2000)

Wilhelmina (Winnie) (who died as a young woman, 1916–1949)

Ann (who died young as a teenager)

Of the six children, the eldest child, Helen Anne (Lenie), had six children, of whom the eldest two were born in Joubert Street. They were Frank William John Gordon (born 14 March 1926) and Rosina Cathrine (Sinnie) Gordon (born 16 November 1927). We know that this young family (Helen Anne (Lenie) and John Henry Gordon) relocated from 7 Joubert Street to Helen’s in-laws by moving to the Gordon property at the bottom of Rustenburg Road in Ida’s Valley in the early years of their daughter Sinnie’s childhood. Today the Gordon property is demolished and is now an open field between St Mark’s Catholic Church and the Ida’s Valley Public Library (In conversation with Colleen Biscombe, 11 May 2018).

We know that ‘P. Okkers’ was a founding member of the politically radical ‘Volkskerk van Afrika’ as of 1921, as he and D. Okkers are mentioned as present at the first meeting in Banhoek Road, at the home address of P.M. Rhode. The church was established as a break-away church from i.a. the Congregational Church and the Rynse Kerk in Stellenbosch on 14 May 1922 (Selwyn 2017:14).

We know that ‘P. Okkers’ and ‘D. Okkers’ were members of the Spes Bona Soccer Club in Ida’s Valley, founded in 1929 and with regular meetings at the home of L. van Sohnen in Andringa Street (Biscombe 2010:69).

We also know that Pieter James Andrew Okkers (1875–1952) was chairperson of the Free Gardeners for three years, and a life-long member of this society. His granddaughter, Elizabeth (Lizzy) Meyer (born Okkers) and her husband, Leonard Meyer, donated a copy of a photograph of Pieter Okkers to the institute. Pieter is pictured dressed in what appears to be gardening apron, and is standing next to a lush vine trellis. His photo bears the inscription ‘R.W.M.’ with dates 1927-1930. According to Leonard, the abbreviation refers to the title of ‘Right Worshipful Master’, and indicates that he was the first chairman of St Pauls’ Lodge no. 4 OFG (Africa)’ of the Order of Free Gardeners for the three years indicated. [17]Leonard Meyer followed up the discussion on the Order of Free Gardeners (OFG) with a whatsapp message (24 September, 2018). The Order of Free Gardeners are similar to the Free Masoners, although with ideological interpretations between the societies that differ. The Free Gardeners are therefore also a somewhat secret society for men, in that women are not members, and the mention of the term of ‘chairman’ in this text is therefore gender specific. Leonard Meyer, who provided the photograph and notebook, was also a chairman of this society from 2001-2004. Leonard occupied a higher-ranked position in the society, as the head of the Order of Free Gardeners (Africa). Meyer’s title was therefore ‘Most Worshipful Grand Master, President, OFG (Africa)’ (In conversation with Leonard Meyer, 12 September 2018). They also lent us a small notebook containing notes written in Pieter’s own writing, in black ink. These notes refer to lists of names, church and other finances, Free Gardener society administration, reflections, advice and personal notes (In conversation with Lizzy and Leonard Meyer, 12 and 14 September 2018).

We know that the Okkers family relocated to Ida’s Valley: We do not know when the Okkers family finally left 7 Joubert Street. We do not know who lived at 7 Joubert Street between the date of their relocation and the purchase of the house by Du Toit.

We know that Harold du Toit and his wife lived in the house until they sold to the University of Stellenbosch. From memoirs of Pieter Conradie (the neighbour at 5 Joubert Street) we know that Harold was an electricity engineer, and that his daughter married a Greek man who owned a vegetable shop on the corner of Merriman and Bird Streets. As an addendum: A website search in 2017 reveals that 7 Joubert Street was last sold in 1973. The 2017 average listing price for the property is indicated as ZAR3 475 000. This figure fell to ZAR3 090 000 when consulted in June 2018 ( http://www.property24.com, accessed 20 October 2017). We know that, had the Okkers family stayed, they would have been forcibly removed from the area by 1964.

We know that Rosina Cathrine (Sinnie) Gordon often told her children, especially Colleen and Hilton, to drive down Joubert Street, because she wanted to see the house where she had been born. She did not know in which one of the two identical single-gabled houses—5 or 7 Joubert Street she had lived, and Hilton and Colleen never took her to find out. They mentioned in June 2018 that they felt they would not have ‘access’ to the houses, as the premises were university student housing and/ or university offices. Sinnie died on 13 June 2017, a few months before I started research on the history of 7 Joubert Street. When Monique Biscombe, with her parents, visited Africa Open Institute on 12 June 2018 for afternoon tea, she related a dream that she had had in the early hours of the morning when she had accidentally been wakened, felt distressed, and then had fallen asleep again—to dream. She dreamed of ‘Ma Sinnie’, who had gathered together her children and grandchildren at Strand Beach, and that she was laughing happily. Monique, who at the time mourned the one-year passing of her grandmother, saw this dream as her grand-

mother’s blessing on the connections and remembrances that had ensued around the address of 7 Joubert Street.

After tea that day, we imprinted Sinnie’s photograph onto the office wall of the Hidden Years archive. In the imprint, looking south through the window, 5 Joubert Street’s north-facing wall and a window is visible. This imprints connects Sinnie to her birth house, whether at 5 or 7 Joubert Street.

Second interlude: 7 Joubert Street, and the Du Toit family

On 22 July 2018 I opened an e-mail that began: ‘Hi Marietjie[,] Yes, Harold du Toit was my grandfather. My father was born in that house in 1959 […]’ Harold Francois du Toit, the grandson of Harold, confirmed that his aunt was Antionette (born 31 Mei 1956, spelling correct), and was married to a Greek person with the surname of Gikas. He also confirmed that his father was still living, and named Francois Harold du Toit (born 30 April 1959). His grandfather, who had bought the house in 1951, and who had lived at 7 Joubert Street from 1951 to 1973, was ‘the Head of Stellenbosch fire brigade as well as an electrical distribution superintendent at the Stellenbosch municipality and Head of the town Hall lighting and sound department.’ His grandfather (Harold du Toit) was born on 7 November 1926. His grandmother’s name was Hester Sophia du Toit (born Joubert, born 12 Mei 1926), and she was from Aberdeen, the daughter of sheep farmers.

Harold du Toit, who bought the property in 1951, was therefore born in the year that the first plans were submitted for the building of 5 Joubert Street (1926): Harold is 51 years younger than Pieter Okkers who had built 7 Joubert Street.

Like 5 Joubert Street, 7 Joubert Street was a family home after Pieter Okkers sold the property: the home was not rental property or student accommodation (until the university purchased it, except for the brief period that the owner had passed away, in the case of 5 Joubert Street). We now know that the Du Toit family lived there for 22 years, and that his grandson, who carries his names, is informed as to where his grandparents (and father and aunt) lived.

We also know that Harold du Toit owned another property in Joubert Street which was rented out for student accommodation (e-mail from Harold Francois du Toit, 22 July 2018). This house was known as ‘Aristos’ (corner of Joubert and Banhoek Streets, Erfs 2436 and 2448), and it was also sold to the University of Stellenbosch ‘for R 33 000’ in 1973 (Pages from the Minutes of 1973a, University Council Meeting, p 29, point 7a, Stellenbosch University Archive). Today these erfs are 14 and 16 Joubert Street. Originally, in 1903, these erfs were assigned to B. Bergsteedt (14) and to P. Hartogh (16).

The Okkers family at 56 Erasmus Smit Street, Ida’s Valley

We know that P. Okkers purchased four properties in Ida’s Valley, including Erf numbers 2875 and 2876 (In conversation with Pieter Okkers, and confirmed by records in the Cape Town Deeds Register).

We know that 56 Erasmus Smit Street was purchased by P. Okkers, with deed transferral on 16 April 1929 (Deeds Register, Cape Town, originally Erf 2876). The Stellenbosch Municipal records indicate no building plans for Erf 2876 (due to subdivision and re-zoning of the property, becoming Erfs 2875 and 4109).

We know that by the time the twins (‘die linge’, Valerie and Valencia, last-borns of Helen Anne (Lenie) and Frank William Gordon) were born in 1946, the Okkers grandparents (Pieter and Rosina C. Okkers) were living at 56 Erasmus Smit Street, Ida’s Valley (In conversation with Colleen Biscombe, 11 May 2018).

We know that Rosina Cathrine (Sinnie), daughter of Lenie and Frank Gordon, celebrated her 21st birthday at the address of 56 Erasmus Smit Street, Ida’s Valley, in 1948 (In conversation with Colleen Biscombe, 11 May 2018).

We do not know when the house at 56 Erasmus Smit Street (subsequently Erf 4109) was built. The Stellenbosch Municipality has two recent alteration applications on file, dated March 1982, and May 1986, and both signed by the architect, W. Okkers (Winston), who is the brother of Pieter Okkers, and who relocated to Australia in 1992.

We know that several newly-married couples, mostly grandchildren of Pieter and Rosina, lived with the grandparents for the first few months of their marriage. Elizabeth (Lizzy) Okkers, for example, lived at 56 Erasmus Smit Street for more than a year after her marriage to Leonard Meyer on 18 March 1967. Their bridal photographs appear in In ons Bloed, where they are photographed in front of the Volkskerk in Ida’s Valley. Names are not included next to the prints of the photographs, but the photo on the left shows Lizzy and her father, Uncle Patsy, whereas the group photo on the right includes the bridal couple (Biscombe 2006:47) (In conversation with Lizzy and Leonard Meyer, 14 and 24 September 2018).

We know that Erf 2876 was subdivided in 1967, with one section transferred to Frank William John Gordon (born 1926). The other section was transferred to Joseph Christian Gabriels (born 1902) and, on his death, to his widow, Cathrine Maria Gabriels, the daughter of Pieter James Andrew Okkers (Deeds Register, Cape Town, originally Erf 2876).

We know that Pieter Okkers (born 1943) and his wife, Sarah (van Niekerk), both employed as teachers before retiring, bought the 56 Erasmus Smit property from Cathrine Maria Gabriels (Pieter’s aunt, Aunty Kate), with the deed transferral registered on 30 August 1974. Aunty Kate retained living rights of a section of the home until her death (In conversation with Pieter and Sarah Okkers). The property was therefore transferred from father to daughter, and then from the aunt to the grandson (of the first owner).

We know that Pieter J. A. Okkers (born 1943) proudly carries the same three names of his grandfather. Pieter and Sarah’s first visit to the grandfather’s house in 7 Joubert Street occurred on 1 August 2018. We had tea together with the institute’s staff, and William Brandt from Jamestown, a cousin of Pieter Okkers (and grandson of Pieter Okkers), also attended the morning tea. Pieter and Williams’s great-grandfather was a carpenter (according to his death certificate) and their grandfather was a builder by trade, the owner and developer of several properties, as well as a furniture maker. (Colleen Biscombe has a fireplace mantelpiece in her home that is an Okkers inheritance, and that came to her through her godmother, Aunty Kate. Pieter Okkers crafted the piece of furniture, as relayed to Colleen by her father, Daniel (Danny) Reginald Gordon.

Pieter’s father (Pieter William James Okkers (Uncle Patsy), 1912–1975) was also employed in the building industry. When Pieter Okkers (born 1943) was an adolescent, his father (Uncle Patsy) took him up on a high-rise construction site in Cape Town where he was working at the time. The heights scared Pieter and he decided to become a teacher instead (In conversation with Pieter Okkers, November 2017).

The Okkers family at 57 Rustenburg Road, Ida’s Valley

The Stellenbosch Municipal records indicate no building plans for Erf 2876 (as the subdivision of the erf necessitated new erf number allocations). Several plans are included for Erf 2875, Rustenburg Road 57. The plans for Erf 2875 date from 1947 (application for a new residence at Rustenburg Road, submitted by P. Okkers, who then indicated his residential address as Erasmus Smit Street). Subsequent plans (for the house at 57 Rustenburg Road) date from 1978 (for Mrs M. Okkers—this is Maria Magdalena Okkers (born Vergotine, 1920-1997), the widow of Uncle Patsy, and the mother of Elizabeth, Pieter Okkers (born 1943), Roseline, and Winston Okkers). Mrs Mary Okkers’s application for the construction of a concrete wall was approved in August 1978. In 1984 she again had plans approved for the construction of a garage. By 1986, her son, Winston Okkers, was the owner and architect of the property at 57 Rustenburg Street, and he built a garage and boundary walls. Further renovations were done in 1987 (additions of a roof window and a balcony). (After this the property was sold and the residents of no. 57, Lionel and Shirley Gordon, relocated to 55 Rustenberg Street. Lionel is the son of Frank Gordon and Sophia Gordon (born Joshua), and the grandson of John Henry Gordon and Helen Anne (Lenie) Gordon, born Okkers.) By the year 2000, the new owner of the property at 57 Rustenburg Road, Mr L. Rogers, applied for the approval of plans for ’alterations to dwelling, Erf 2875’.

The University of Stellenbosch at 7 Joubert Street, 1973–2018

The University of Stellenbosch used the house at 7 Joubert Street for various institutions and service departments. In 1973, 7 Joubert Street was made available as premises for the accommodation needs of medical services for students (‘om in die akkommodasie-behoeftes van die geneeskundige diens vir studente te voorsien’) (Pages from the Minutes of 1973b, University Council Meeting, p 14, point 9, Stellenbosch University Archive).

In 1977 the service department Student Health (‘Afdeling Studentegesondheidsdiens’) used the premises (Pages from the Minutes of 1977, University Council Meeting, p 294, point 5, Stellenbosch University Archive). Later in 1977, the University of Stellenbosch Clinics Organisation (‘Universiteit van Stellenbosch se Klinieke Organisasie’: USKOR) were housed on the premises (Pages from the Minutes of 1977, University Council Meeting, p 297, point 5, Stellenbosch University Archive). [18]USKOR was established in 1964 by the first medical students to study at SU (http://www.scielo.org.za/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1021-545X2017000200001accessed 4 November 2017). USKOR became Matie Health Services/ Matie Gesondheidsdiens (MGD) in 1997.instagram twitter.com

In 1981 the premises were made available for visiting sportsmen and other critical temporary accommodation needs (‘die huisvesting van besoekende sportmanne asook tydelike huisvesting van manstudente [sic] in noodgevalle wat periodiek voorkom’) (Pages from the Minutes of 1980, University Council Meeting p 224, Stellenbosch University Archive).

In 1984 the Institute for Theoretical Nuclear Physics (Instituut vir Teoretiese Kernfisika), which had links to the Nuclear Energy Corporation (‘Atoomenergie Korporasie’: AEK, established by Chris Engelbrecht) used the premises. The institute formally inaugurated the premises on 7 June 1984. In an e-mail from Hendrik Geyer, who was part of this institute, he comments wryly that Africa Open Institute had some roots also in theoretical physics (‘wortels eintlik ook in teoretiese fisika’) (e-mail 3 July 2018). In 1990 the Nuclear Energy Corporation withdrew its support, and the Institute changed its name to the Institute for Theoretical Physics.

Fritz Hahne, Frederik Scholtz, Hendrik Geyer, Chris Engelbrecht

In 2006 the premises were used as a service point for students who required assistance from the Department Information Technology (e-mails from: Louma Engelbrecht, 6 November 2017; and Francois Swart, 7 November 2017).

In 2014 the premises were awarded to Stellenbosch University Housing Services, and to Commercial Services (e-mail from Louma Engelbrecht, 6 November 2017).

In October 2017 the newly formed Africa Open Institute for Music, Research and Innovation [19]The establishment of Africa Open Institute (AOI) was made possible by the announcement (in December 2015) of a successful Mellon funding grant, titled Delinking Encounters, initiated by current AOI director, Prof. Stephanus Muller, with support from i.a. the current AOI manager, Dr Hilde Roos. The University of Stellenbosch approved the establishment of the institute on 11 June 2016. One and a half years later, by October 2017, the institute was given access to rental premises in 7 Joubert Street (Muller 2018). The website of AOI was launched in July 2018. See www.aoinstitute.ac.za. The inauguration of AOI was held on 9 October 2018. began to use the premises and a careful process of interior renovation was initiated. The institute was inaugurated on Tuesday evening 9 October 2018. The evening incorporated the naming of the house in honour of the person who built the house, as well as a book launch of the third print of In ons Bloed by Hilton Biscombe. The evening also comprised music performances (music by Michael Blake, Pierre-Henri Wicomb and Seth van Graan), two film screenings (A State of Grace, and Die Storie van ’n Boek (both by Biscombe, 2018) as well as addresses by the university rector, Prof Wim de Villiers, Dr Jerome Slamat (who was involved with the writing of the book), members of the Okkers family (Colleen Biscombe and Pieter Okkers) and speakers from AOI (Director Stephanus Muller, and myself).

Pieter Okkers-huis